Empresario

An empresario [em.pɾe.ˈsaɾ.jo] was a person who had been granted the right to settle on land in exchange for recruiting and taking responsibility for settling the eastern areas of Coahuila y Tejas in the early nineteenth century. The word in Spanish for entrepreneur is emprendedor (from empresa, "company").[1]

Since empresarios attracted immigrants mostly from the Southern United States, they encouraged the spread of slavery into Texas. Although Mexico banned slavery in 1829, the settlers in Texas revolted in 1835 and continued to develop the economy, dominated by slavery, in the eastern part of the territory.

Background

.jpg)

In the late 18th century, Spain stopped allocating new lands in much of Spanish Texas, stunting the growth of the province.[2] It changed this policy in 1820, and made it more flexible, allowing colonists of any religion to settle in Texas (formerly settlers were required to be Catholic, the established religion of the Spanish Empire).[3] Moses Austin, a British colonist, was the only man granted an empresarial contract in Texas under Spanish law. But Moses Austin died before he could begin his colony, and Mexico achieved its independence from Spain in September 1821. At this time, about 3500 colonists lived in Texas, mostly congregated at San Antonio and La Bahia.[4]

The Mexican government continued the generous immigration policies in order to develop east Texas.[5] Even as the government debated a new colonization law, Stephen F. Austin, son of Moses Austin, was given permission to take over his father's colonization contract. Steven F. Austin is probably the best known and most successful empresario in Texas. The first group of colonists, known as the Old Three Hundred, arrived in 1822 and settled along the Brazos River, ranging from the Gulf of Mexico to near present-day Dallas.[6]

In 1823, Mexico’s authoritarian ruler Agustín de Iturbide enacted a colonization law authorizing the national government to enter into a contract granting land to an “empresario,” or promoter, who was required to recruit a minimum of two hundred families to settle the grant.[7]

Mexico approved immigration on a wider basis in 1824 with passage of the General Colonization Law. This law authorized all heads of household who were citizens of or immigrants to Mexico as eligible to claim land.[5] After the law passed, the state government of Coahuila y Tejas was inundated with requests by foreign speculators to establish colonies within the state.[8] There was no shortage of people willing to come to Texas. The United States was still struggling with the aftermath of the Panic of 1819, and soaring land prices within the United States made the Mexican land policy seem very generous.[8]

Most successful empresarios recruited colonists primarily in the United States. Only two of the groups that attempted to recruit in Europe built lasting colonies, Refugio and San Patricio.[9][10] These colonies were successful in part because the empresarios spoke Spanish, were Catholic and generally familiar with Mexican ways, and allowed local Mexican families to join their colonies.[10]

In 1829, Mexico abolished slavery, which affected the Anglo-American settlers’ quest for wealth in building colonizations worked by enslaved Africans. They lobbied the Mexican government for a reversal of the ban and gained only a one-year extension to settle their affairs and free their bonded workers - the government refused to legalize slavery. The settlers decided to secede from Mexico, initiating the famous and mythologized Battle of the Alamo in 1836.[11]

Rules for settlers

Unlike its predecessor, the Mexican law required immigrants to practice Catholicism and stressed that foreigners needed to learn Spanish.[12] Settlers were supposed to own property or have a craft or useful profession, and all people wishing to live in Texas were expected to report to the nearest Mexican authority for permission to settle. The rules were widely disregarded and many families became squatters.[13]

Under the new laws, people who did not already possess property in Texas could claim 4438 acres of irrigable land, with an additional 4438 available to those who owned cattle. Empresarios and individuals with large families were exempt from the limit.[14]

Notable empresarios

| Empresario | Colony location | Capital | Notes

Empresido of Mexico in New Madrid, Spanish Louisiana Territory, |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philip Alston (counterfeiter) | New Madrid, Spanish Louisiana Territory | New Orleans | sold land grants |

| Stephen F. Austin | Austin's Colony between Brazos and Colorado rivers | San Felipe De Austin | took over his father Moses Austin's empresario contract |

| David G. Burnet | East Texas, northwest of Nacogdoches | sold his land grant to the Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company | |

| Martín De León | De León's Colony | Victoria | The only colony that was primarily Mexican and not Anglo-American[15] |

| Green DeWitt | DeWitt Colony | Gonzales | |

| Haden Harrison Edwards | East Texas – from the Navasota River to 20 leagues west of the Sabine River, and from 20 leagues north of the Gulf of Mexico to 15 leagues north of the town of Nacogdoches.[16] | Nacogdoches | Expelled from Texas after launching the Fredonia Rebellion in 1827 |

| Benjamin Drake Lovell and John Purnell | Attempted to establish a socialist colony; Purnell died and Lovell abandoned the colony in 1826; land was later given to McMullen and McGloin.[17] | ||

| John McMullen and James McGloin | San Patricio, TX | of Irish descent, these men recruited primarily European settlers[10][18] | |

| James Power and James Hewetson | Land between Guadalupe and Lavaca rivers.[19] | San Patricio and Refugio | Half of settlers were to come from Ireland, the other half from Mexico.[20] |

| Sterling C. Robertson | An area along the Brazos River about 100 miles wide and 200 miles long, centered on Waco, comprising all or some of thirty present-day counties in Central Texas.[21] | Sarahville | At various times also called Robertson's Colony, the Texas Association, Leftwich's Grant, the Nashville colony, or the upper colony.[21] |

| Lorenzo de Zavala | southeastern Texas in the Galveston Bay Area | transferred ownership to the Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company | |

| Henri Castro | southwestern Texas on the Medina River | Castroville |

After the Republic of Texas won its independence from Mexico, the young nation continued its own version of the empresario program, offering grants to French diplomat Henri Castro and abolitionist Charles Fenton Mercer, among others.

See also

- Patroon (a similar system in New Netherland)

References

- Compare "impresario".

- Manchaca (2001), p. 194.

- Vazquez (1997), p. 48.

- Edmondson (2000), p. 75.

- Manchaca (2001), p. 187.

- Manchaca (2001), p. 198.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2014). An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8070-5783-4.

- Vazquez (1997), p. 53.

- Davis (2002), p. 72.

- Davis (2002), p. 75.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2014). An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8070-5783-4.

- Vazquez (1997), p. 50.

- de la Teja (1997), p. 88.

- Manchaca (2001), p. 196.

- Henderson, p.5

- Ericson (2000), p. 37.

- Davis (2002), p. 76.

- Davis (2002), p. 73.

- Davis (2002), p. 78.

- Davis (2002), p. 79.

- Texas State Historical Association

Sources

- Davis, Graham (2002), Land!: Irish Pioneers in Mexican and Revolutionary Texas, Centennial Series of the Association of Former Students, Texas A&M University; No. 92, College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 978-1-58544-189-1

- de la Teja, Jesus F. (1997), "The Colonization and Independence of Texas: A Tejano Perspective", in Rodriguez O., Jaime E.; Vincent, Kathryn (eds.), Myths, Misdeeds, and Misunderstandings: The Roots of Conflict in U.S.–Mexican Relations, Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc., ISBN 0-8420-2662-2

- Edmondson, J.R. (2000), The Alamo Story-From History to Current Conflicts, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press, ISBN 1-55622-678-0

- Ericson, Joe E. (2000), The Nacogdoches story: an informal history, Heritage Books, ISBN 978-0-7884-1657-6

- Manchaca, Martha (2001), Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans, The Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-75253-9

- Vazquez, Josefina Zoraida (1997), "The Colonization and Loss of Texas: A Mexican Perspective", in Rodriguez O., Jaime E.; Vincent, Kathryn (eds.), Myths, Misdeeds, and Misunderstandings: The Roots of Conflict in U.S.–Mexican Relations, Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc., ISBN 0-8420-2662-2

- Henderson, Mary Virginia (July 1928). "Minor Empresario Contracts for the Colonization of Texas, 1825-1834, II". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. Texas State Historical Association. 32 (1): 1–28. JSTOR 30235006.

External links

Maps:

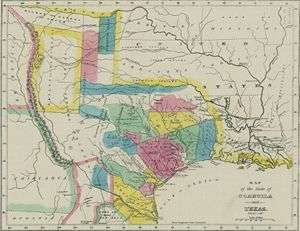

- Texas Land Grants and Political Divisions, 1821–1836, from the Atlas of Texas, 1976

- T. G. Bradford's Map of Texas, 1835

Soccer