Medina River

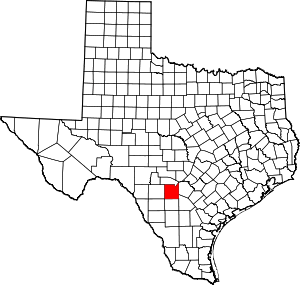

The Medina River is located in south central Texas, United States, in the Medina Valley. It was also known as the Rio Mariano, Rio San Jose, or Rio de Bagres (Catfish river). Its source is in springs in the Edwards Plateau in northwest Bandera County, Texas and merges with the San Antonio River in southern Bexar County, Texas, for a course of 120 miles. It contains the Medina Dam in NE Medina County, Texas which restrains Lake Medina. Much of its course is owned and operated by the Bexar-Medina-Atascosa Water District to provide irrigation services to farmers and ranches.

| Medina River Río Mariano, Río San Jose, Río de Bagres | |

|---|---|

Medina River near Bandera, Texas | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Bandera County, Texas |

| • coordinates | 29°47′46″N 99°15′19″W[1] |

| Mouth | San Antonio River |

• location | Bexar County, Texas |

• coordinates | 29°14′04″N 98°24′28″W[1] |

• elevation | 128 m (420 ft) |

History

The Medina River was named after Pedro de Medina, a Spanish cartographer, by Alonso de León, Spanish governor of Coahuila, New Spain in 1689. It once served as the official boundary between Texas and Coahuila with the San Antonio River being considered its tributary. At that time, the river was called the Medina all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, but now the part below the confluence is called the San Antonio River.

From 1849, Castroville on the river was a water stop on the San Antonio-El Paso Road and a stagecoach station on the San Antonio-El Paso Mail and San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line.

Natural features

Much of the source water to the Medina River is produced by springs emerging due to the presence of the Balcones Fault. This locale of the Balcones Fault is associated with an important ecological dividing line for species occurrence. For example, species such as the California Fan Palm, Washingtonia filifera, occur only west of the Medina River or Balcones Fault.[2]

The Medina River once received significant waste discharge from upstream catfish farming operations, which utilized more water than was sustainable to the basin's safe usage.[3]

See also

Notes

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Medina River

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009

- Robert Glennon. 2004

References

- Robert Glennon. 2004. Water Follies: Groundwater Pumping and the Fate of America's Fresh Waters, Island Press, 314 pages ISBN 1-55963-400-6, ISBN 978-1-55963-400-7

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009. California Fan Palm: Washingtonia filifera, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. Nicklas Stromberg

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Medina River. |

- Medina River from the Handbook of Texas Online