Electricity sector in New Zealand

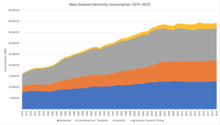

The electricity sector in New Zealand uses mainly renewable energy sources such as hydropower, geothermal power and increasingly wind energy. 82%[1] of energy for electricity generation is from renewable sources, making New Zealand one of the lowest carbon dioxide emitting countries in terms of electricity generation. Electricity demand has grown by an average of 2.1% per year from 1974 to 2010 but decreased by 1.2% from 2010 to 2013.[3][4]

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Installed capacity (2017) | 9,237 MW[1] |

| Production (2017) | 42,911 GWh[1] |

| Share of fossil energy | 18%[1] |

| Share of renewable energy | 82%[1] |

| GHG emissions from electricity generation (2011) | 4,843 kilotonnes CO2-e[2] |

| Average electricity use (2017) | 8,940 kWh per capita[1] |

| Distribution losses (2017) | 6.8 percent[1] |

| Residential consumption | 31 percent% |

| Industrial consumption (% of total) | 43 percent |

| Commercial and public consumption (% of total) | 24 percent |

| Average residential tariff (US$/kW·h, 2017) | 0.19 (NZ$ 0.29)[1] |

| Services | |

| Share of private sector in generation | 36% |

| Share of private sector in transmission | 0% |

| Share of private sector in distribution | 100% |

| Competitive supply to large users | Yes, except in isolated areas |

| Competitive supply to residential users | Yes, except in isolated areas |

| Institutions | |

| Responsibility for transmission | Transpower |

| Responsibility for regulation | Electricity Authority Commerce Commission |

| Electricity sector law | Electricity Act 1992 Electricity Industry Act 2010 |

Regulation of the electricity market is the responsibility of the Electricity Authority (formerly the Electricity Commission). Electricity lines businesses, including Transpower and the distribution lines companies, are regulated by the Commerce Commission. Control is also exerted by the minister of energy in the New Zealand Cabinet, though the minister for state-owned enterprises and the minister for climate change also have some powers by virtue of their positions and policy influence in the government.

History

In New Zealand electricity was first generated within factories for internal use. The first generation plant where power left the building was established at Bullendale in Otago in 1885, to provide power for a twenty stamp battery at the Phoenix mine. The plant used water from the nearby Skippers Creek, a tributary of the Shotover River.[5][6]

Reefton on the West Coast became the first electrified town in 1888 after the Reefton Power Station was commissioned, while the first sizable power station was built for the Waihi gold mines at Horahora on the Waikato River. This set a precedent that was to dominate New Zealand's electricity generation, with hydropower becoming and remaining the dominant source.[7] From 1912 to 1918 the Public Works Department issued licenses for many local power stations.[8] By 1920, there were 55 public supplies, with 45 megawatts of generating capacity between them.[9]

Early public electricity supplies used various voltage and current standards. The 230/400-volt 50-hertz three-phase system was chosen as the national standard in 1920.[10] At the time, 58.6% of the country's generating capacity used the 50 Hz three-phase system; 27.1% used direct current systems while 14.3% used other alternating current standards.[9]

While industrial use quickly took off, it was only government programmes in the first two-thirds of the 20th century that caused private demand to climb strongly as well. Rural areas were particular beneficiaries of subsidies for electrical grid systems, where supply was provided to create demand, with the intention of modernising the countryside. The results were notable – in the 1920s, electricity use increased at a rate of 22% per year. In fact, the 'load building' programmes were so successful that shortages started to occur from 1936 on, though a large number of new power stations built in the 1950s enabled supply to catch up again.[7]

After the massive construction programmes had created a substantial supply of energy not dependent on international fossil fuel prices, New Zealand became less frugal with its energy use. While in 1978, its energy consumption (as expressed against economic output) hovered around the average of all OECD countries, during the 1980s New Zealand dropped far behind, increasing its energy use per economic unit by over 25%, while other nations slowly reduced their energy usage levels. Based on this economic comparison, in 1991 it was the second-least energy-efficient country out of 41 OECD countries.[4]

All of the government's energy assets originally came under the Public Works Department. From 1946, the management of generation and transmission came under a new department, the State Hydro-Electric Department (SHD), renamed in 1958 as the New Zealand Electricity Department (NZED). In 1978, the Electricity Division of the Ministry of Energy assumed responsibility for electricity generation, transmission, policy advice and regulation.[11] Distribution and retailing was the responsibility of local electric power boards (EPBs) or municipal electricity departments (MEDs).

New Zealand's electrical energy generation, previously state-owned as in most countries, was corporatised, deregulated and partly sold off over the last two decades of the twentieth century, following a model typical in the Western world. However, much of the generation and retail sectors, as well as the entire transmission sector, remains under government ownership as state-owned enterprises.

The Fourth Labour Government corporatised the Electricity Division as a State Owned Enterprise in 1987, as the Electricity Corporation of New Zealand (ECNZ), which traded for a period as Electricorp. The Fourth National Government went further with the Energy Companies Act 1992, requiring EPBs and MEDs to become commercial companies in charge of distribution and retailing.

In 1994, ECNZ's transmission business was split off as Transpower. In 1996, ECNZ was split again, with a new separate generation business, Contact Energy, being formed. The Fourth National Government privatised Contact Energy in 1999. From 1 April 1999, the remainder of ECNZ was split again, with the major assets formed into three new state-owned enterprises (Mighty River Power (now Mercury Energy), Genesis Energy and Meridian Energy) and with the minor assets being sold off. At the same time, local power companies were required to separate distribution and retailing, with the retail side of the business sold off, mainly to generation companies.

Organisation

New Zealand's electricity sector is split into six distinct parts:

- Generation – Generation companies generate electricity at power stations, selling the electricity generated via the wholesale market to retailers while physical electricity is injected into either transmission lines (grid-connected generation) or distribution lines (embedded generation). Numerous companies generate power, but 92 percent of the generation sector is dominated by five companies: Contact Energy, Genesis Energy, Meridian Energy, Mercury Energy and Trustpower.

- Transmission – Transpower operates the national transmission network, consisting of 11,000 km of high voltage lines interconnecting generating power stations with grid exit points to supply distribution networks and large industrial consumers (direct consumers) in each of New Zealand's two main islands. A 611 km high voltage direct current link (HVDC Inter-Island) connects the two islands' transmission networks together.

- Distribution – Distribution companies operate 150,000 km of medium and low-voltage lines interconnecting grid exit points with consumers and embedded generation. There are 29 distribution companies each serving a set geographic area.

- Retail – Retail companies buy electricity from generators and on-sell it to consumers. Numerous companies retail electricity, including many generating companies, but 95 percent of the retail sector is dominated by five companies: Contact Energy, Genesis Energy, Mercury Energy, Meridian Energy and Trustpower.

- Consumption – Nearly two million consumers take electricity from the distribution networks or the transmission network and buy electricity from retailers for their use. Consumers range from typical households, which consume on average 8–9 MWh per year, to the Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter, which consumes 5,400,000 MWh per year.

- Regulation – New Zealand's Electricity Authority is responsible for management of the electricity industry, while Transpower as System Operator manages the electricity system in real time to ensure generation matches demand. Policy and governance is managed by the New Zealand Government and several Crown entities, including the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, the Commerce Commission, and the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority.

Regulation and policy

Renewable energy sources provide much of the nation's electricity production, with the New Zealand energy industry for example reporting a 75% share in 2013.[3] The Fifth Labour Government of New Zealand had the goal of increasing this to 90% by 2025,[12] the subsequent Fifth National Government put priority on security of supply.[13]

New Zealand's Labour government introduced a number of measures in the 2000s as part of the vision of New Zealand becoming carbon neutral by 2020,[14][15] and intended to collect levies for greenhouse effect emissions from 2010 onwards, to be added to power prices depending on the level of emissions.[16] However, the incoming National government quickly tabled legislation to repeal various of these measures, such as obligatory targets for biofuel percentages,[17] a ban on construction of new fossil fueled generation plants[18] and a ban on future sales of incandescent light bulbs.[19]

On 1 January 2010, the energy sector was required to report greenhouse gas emissions under the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZETS). From 1 July 2010, the energy sector had formal compliance obligations to buy and surrender one emission unit for every two tonnes of reported emissions. As of December 2011, there were 78 energy firms compulsorily registered in the NZETS and five voluntary participants.[20] Energy sector firms in the NZETS do not receive a free allocation of emissions units and they are expected to pass on to their customers the costs of buying emission units.[21]

In April 2013, the Labour Party and the Green Party said if they were to win the 2014 general election, they would introduce a single buyer of electricity akin to Pharmac (the single buyer of pharmaceutical drugs in New Zealand), in order to cut retail costs.[22] The Government responded by calling it "economic vandalism", comparing it to the Soviet Union,[23] but Greens co-leader Russel Norman said it would boost the economy and create jobs.[24] By the following day, shares in privately owned power company Contact Energy had fallen by more than 10 percent.[25]

Electricity market

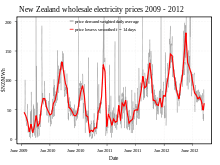

Electricity is traded at a wholesale level in a spot market. The market operation is managed by several service providers under agreements with the Electricity Authority.[26] The physical operation of the market is managed by Transpower in its role as System Operator.

Generators submit offers (bids) through a Wholesale Information and Trading System (WITS). Each offer covers a future half-hour period (called a trading period) and is an offer to generate a specified quantity at that time in return for a nominated price. The System Operator (Transpower) uses a scheduling, pricing and dispatch (SPD) system to rank offers, submitted through WITS, in order of price, and selects the lowest-cost combination of offers (bids) to satisfy demand.

The market pricing principle is known as bid-based security-constrained economic dispatch with nodal prices.

The highest-priced bid offered by a generator required to meet demand for a given half-hour sets the spot price for that trading period.

Electricity spot prices can vary significantly across trading periods, reflecting factors such as changing demand (e.g. lower prices in summer when demand is subdued) and supply (e.g. higher prices when hydro lakes and inflows are below average). Spot prices can also vary significantly across locations, reflecting electrical losses and constraints on the transmission system (e.g. higher prices in locations further from generating stations).

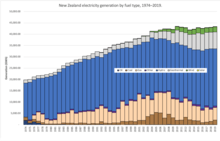

Generation

In 2017, New Zealand generated 42,911 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electricity with hydroelectricity making up just over half of this. The installed generating capacity of New Zealand (all sources) as of December 2017 was 9,237 megawatts (MW), with hydroelectricity, natural gas, geothermal, wind, coal, oil, and other sources (mainly biogas, waste heat and wood) featuring. Note that some power stations can use more than one fuel, so their capacity (see below table) has been split in line with the amount of electricity generated by each fuel.[1]

Comparing the two main islands, nearly all South Island's electricity is generated by hydroelectricity – 98% in 2014. The North Island has a wider spread of generation sources with geothermal, natural gas and hydroelectricity all generating a share of between 20–30% each in 2014.[3]

|

|

| Year | Hydro | Geothermal | Biogas | Wood | Wind | Solar | Thermal | Total | % Renewable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | 16,497 | 1,350 | 41 | 306 | – | – | 1,926 | 20,120 | 90% |

| 1980 | 19,171 | 1,206 | 57 | 306 | – | – | 1,972 | 22,713 | 91% |

| 1985 | 19,511 | 1,165 | 105 | 336 | – | – | 6,572 | 27,689 | 76% |

| 1990 | 22,953 | 2,011 | 131 | 336 | – | – | 6,028 | 31,459 | 81% |

| 1995 | 27,259 | 2,039 | 172 | 336 | 1 | – | 5,442 | 35,250 | 85% |

| 2000 | 24,191 | 2,756 | 103 | 447 | 119 | – | 10,454 | 38,069 | 73% |

| 2005 | 23,094 | 2,981 | 190 | 277 | 608 | – | 14,289 | 41,438 | 66% |

| 2010 | 24,479 | 5,535 | 218 | 345 | 1,621 | 4 | 11,245 | 43,445 | 74% |

| 2015 | 24,285 | 7,410 | 244 | 349 | 2,340 | 36 | 8,231 | 42,895 | 81% |

| 2018 | 26,027 | 7,510 | 261 | 289 | 2,047 | 98 | 6,895 | 43,126 | 84% |

Hydro

Hydroelectric power stations generate the majority of New Zealand's electricity, with 22,815 GWh generated by hydroelectricity in 2013 – 55 percent of New Zealand's electricity generated that year. The total hydroelectricity installed capacity is 5,262 MW.[3] The South Island is heavily reliant on hydroelectricity, with 98% of its electricity generated by hydroelectricity in 2013.

There are three major hydroelectric schemes in the South Island: Waitaki, Clutha and Manapouri. Waitaki has three distinct parts – the original Waitaki and Tekapo A powerhouses (1936 and 1951 respectively), the 1960s Lower Waitaki development consisting of Benmore and Aviemore, and the 1970–80s Upper Waitaki development of Tekapo B and Ohau A, B, and C. In total, the nine powerhouses generate approximately 7600 GWh annually, around 18% of New Zealand's electricity generation[28] and more than 30% of all its hydroelectricity.[29] Manapouri Power Station is a single underground power station in Fiordland, and the largest hydroelectric station in the country. It generates 730 MW of electricity and produces 4800 GWh annually, mainly for the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter near Invercargill. Both Waitaki and Manapouri are operated by Meridian Energy. The Clutha River scheme is operated by Contact Energy, and consists of two powerhouses: Clyde Dam (464 MW, commissioned 1992) and Roxburgh Dam (320 MW, commissioned 1962).

The North Island has two major schemes: Tongariro and Waikato. The Tongariro Power Scheme consists of water taken from the catchments of the Whangaehu, Rangitikei, Whanganui and Tongariro Rivers passing through two powerhouses (Tokaanu and Rangipo) before being deposited in Lake Taupo. The scheme is operated by Genesis Energy and has an installed capacity of 360 MW. The Waikato River Scheme, operated by Mercury Energy, consists of nine powerhouses on the river between Lake Taupo and Hamilton, generating 3650 GWh annually.

Other smaller hydroelectricity facilities and schemes are scattered around both islands of mainland New Zealand.

Hydroelectric schemes have largely shaped hinterland New Zealand. Towns including Mangakino, Turangi, Twizel and Otematata originally were founded for workers on the construction of hydroelectric schemes and their families. The hydroelectric reservoirs of Lake Ruataniwha and Lake Karapiro are world-class rowing venues, with the latter having hosted the 1978 and the 2010 World Rowing Championships. Other schemes have shaped political New Zealand. In the 1970s, the original plans to raise Lake Manapouri for the Manapouri station were scrapped after major protests. Later in the 1980s, protests were made against the creation of Lake Dunstan behind the Clyde Dam, which would flood the Cromwell Gorge and part of Cromwell township, destroying many fruit orchards and the main street of Cromwell. However, the project was given the go ahead and Lake Dunstan was filled in 1992–93.

Hydroelectricity generation has remained relatively steady since 1993 – the only major hydroelectricity projects since then was the completion of the second Manapouri tailrace tunnel in 2002, increasing the station from 585 MW to 750 MW, and due to resource consent the station increases further to 800 MW.[30] No major new hydroelectric projects have been committed as of December 2011, but there are proposals for further developments on the Waitaki and Clutha Rivers, and on the West Coast of the South Island.

Geothermal

New Zealand lies on the Pacific Ring of Fire, creating favourable geological conditions for the exploitation of geothermal power. Geothermal fields have been located across New Zealand, but at present, most geothermal power is generated within the Taupo Volcanic Zone – an area in the North Island stretching from Mount Ruapehu in the south to White Island in the north. As at December 2012, the installed capacity of geothermal power was 723 MW, and in 2013, geothermal generated 6,053 GWh of electricity – 15% of the country's electricity generation that year.[3]

The majority of New Zealand's geothermal power is generated north of Lake Taupo. Eight stations generate electricity here, including Wairakei Power Station, New Zealand's oldest (1958) and largest (176 MW) geothermal power station, and the world's second large-scale geothermal power facility. Also in this area are Nga Awa Purua, which is home to the world's largest geothermal turbine at 147 MW[31] (although the plant only generates 140 MW); and Ohaaki, which has a 105-metre tall hyperboloid natural draft cooling tower: the only one of its kind in New Zealand. A significant amount of geothermal electricity is also generated near Kawerau in the eastern Bay of Plenty, and a small amount is generated near Kaikohe in Northland.

Much of New Zealand's geothermal power potential still lies untapped, with the New Zealand Geothermal Association estimating an installation capacity (using only existing technology) of around 3,600 MW.[32]

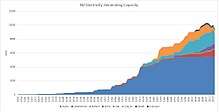

Wind

According to a 2018 report published by the New Zealand government, wind generation provided 5% of the electricity supply for 2017. This was down from 7% in 2016 and 9% in 2015. As of 2018, wind power accounts for 690 MW of installed capacity.[33] Consents have been granted for wind farms with a further capacity of 2,500 MW.[34]

New Zealand has abundant wind resources. The country is in the path of the Roaring Forties, strong and constant westerly winds, and the funneling effect of Cook Strait and the Manawatu Gorge increase the resource's potential. These effects make the Lower North Island the main region for wind generation. About 70 percent of the nation's current installed capacity lies within this region, with some turbines have a capacity factor of over 50 percent in this area.[35]

Electricity was first generated by wind in New Zealand in 1993, by a 225 kW demonstration turbine in the Wellington suburb of Brooklyn. The first commercial wind farm was established in 1996 – the Hau Nui Wind Farm, 22 km southeast of Martinborough had seven turbines and generated 3.85 MW. The Tararua Wind Farm was first commissioned in 1999 with 32 MW of generating capacity, gradually expanding over the next eight years to 161 MW – the largest wind farm in New Zealand. Other major wind farms include Te Apiti, West Wind and White Hill.

Wind power in New Zealand shares the difficulties typical to other nations (uneven wind strengths, ideal locations often remote from power demand areas). New Zealand wind farms provide on average a 45% capacity factor (in other words, wind farms in New Zealand can produce more than double their average energy during periods of maximum useful wind strengths). The Tararua Wind Farm averages slightly more than this.[14] The New Zealand Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority figures indicate that wind power is also expected to operate at maximum capacity for around 4,000 hours a year, much more than for example the approximately 2,000 hours (Germany) to 3,000 hours (Scotland, Wales, Western Ireland) found in European countries.[14]

Fossil fuels

Fossil fuels, specifically coal, oil and gas, produced 10,383 GWh of electricity in 2013 – 25% of all electricity generated that year. This was split into 8,143 GWh by gas, 2,238 GWh by coal, and 3 GWh by oil. Total combined installed capacity in 2012 was 2,974 MW. The North Island generates nearly all of New Zealand's fossil-fuelled electricity.[3]

Up until the 1950s, fossil-fuelled stations were small-scale and usually fuelled by coal or coal by-products, providing electricity to cities yet to be connected to hydro schemes and to provide additional support to such schemes. Large-scale coal-fired generation came in 1958 with the establishment of the 210 MW Meremere Power Station. Oil-fired stations such as Otahuhu A, Marsden A&B, and New Plymouth were commissioned in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The discovery of natural gas off the Taranaki coast, and the oil crises of the 1970s, saw oil-fueled stations converted to gas operation or mothballed, while gas-fired stations proliferated, especially in Taranaki and Auckland, well into the 2000s. Only in recent years has coal made a comeback, as Taranaki gas has slowly depleted.

Today, there are three major fossil-fuelled stations in New Zealand. Smaller gas- and coal-fuelled industrial generators are found across New Zealand and especially in Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, and Taranaki. Genesis Energy's Huntly Power Station in northern Waikato is New Zealand's largest power station – with 1000 MW of coal- and gas-fired generators and 435 MW of gas only generators, it supplies around 17% of the country's electricity.[36] A gas-fired power station exists in Taranaki at Stratford (585 MW). Whirinaki is a 155 MW diesel-fired station north of Napier, providing backup generation for periods when generation is not otherwise available, such as when plants break down, or during dry seasons where there is limited water available for hydroelectricity generation.

Diesel-fuelled generation using internal combustion engines is popular in hinterland New Zealand where the national network doesn't reach, such as on offshore islands, alpine huts, sparsely populated areas and isolated homes and farm sheds. Diesel fuel suitable for generators is readily available across the country at petrol stations – diesel is not taxed at the petrol pump in New Zealand, and instead diesel-powered vehicles pay Road User Charges based on their gross tonnage and distance travelled.

As of 2012 none of the power generators appear to be committed to the construction of any new fossil-fuelled power stations. However, for several years there have been two unactioned but reasonably well defined proposals for gas-fired power stations with 880 MW of generating capacity in the Auckland area. Both the proposed Rodney Power Station (Genesis Energy) near Helensville and the proposed Otahuhu Power Station C plant (Contact Energy) have resource consents.

Other sources

Solar

As of January 2019 the installed solar generation capacity of 90.1MW represented just 1% of New Zealand generation capacity.[37]

Marine

New Zealand has large ocean energy resources but does not yet generate any power from them. TVNZ reported in 2007 that over 20 wave and tidal power projects are currently under development.[38] However, not a lot of public information is available about these projects. The Aotearoa Wave and Tidal Energy Association was established in 2006 to "promote the uptake of marine energy in New Zealand". According to their latest newsletter,[39] they have 59 members. However the association doesn't list these members or provide any details of projects.[40]

From 2008 to 2011, the government Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority allocated $2 million each year from a Marine Energy Deployment Fund, set up to encourage the utilisation of this resource.[41]

The greater Cook Strait and Kaipara Harbour seem to offer the most promising sites for using underwater turbines. Two resource consents have been granted for pilot projects in Cook Strait itself and in the Tory Channel, and consent has been granted for up to 200 tidal turbines at the Kaipara Tidal Power Station. Other potential locations include the Manukau and Hokianga Harbours, and French Pass. The harbours produce currents up to 6 knots with tidal flows up to 100,000 cubic metres a second. These tidal volumes are 12 times greater than the flows in the largest New Zealand rivers.

.jpg)

Nuclear

Although New Zealand has nuclear-free legislation, it covers only nuclear-propelled ships, nuclear explosive devices and radioactive waste.[42][43] The legislation does not prohibit the building and operation of a nuclear power station.

The only significant proposal for a nuclear power station in New Zealand was the Oyster Point Power Station, on the Kaipara Harbour near Kaukapakapa north of Auckland. Between 1968 and 1972, there were plans to develop four 250 MW reactors at the site. By 1972, the plans were dropped as the discovery of the Maui gas field meant there was no immediate need to embark on a nuclear programme.[42] Since 1976, the idea of nuclear power, especially in the Auckland region, has popped up from time to time, but there are no definite plans.

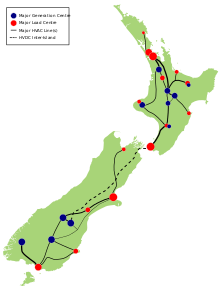

Transmission

New Zealand's national electricity transmission grid connects its generating facilities to its demand centres, which are often more than 150 km (93 mi) from each other. The national grid is owned, operated and maintained by state-owned enterprise Transpower New Zealand. The grid contains 11,803 kilometres (7,334 mi) of high-voltage lines and 178 substations.[44]

The first major transmission lines were built in 1913–14, connecting the Horahora hydro station to Waikino, and Coleridge hydro station with Addington in Christchurch. The interwar years saw the first major construction of a national network of 110 kV lines connecting towns and cities to hydroelectric schemes. By 1940, the transmission network stretched from Whangarei to Wellington in the North Island, and Christchurch to Greymouth and Invercargill in the South Island. Nelson and Marlborough, the last regions, joined the national grid in 1955. The 220 kV network began in the early 1950s, connecting the Waikato River dams to Auckland and Wellington, and Roxburgh Dam to Christchurch. The two islands were joined together by the HVDC Inter-Island link in 1965. The first 400 kV transmission line was completed between Whakamaru Dam on the Waikato River and Brownhill substation east of Auckland in 2012, but presently is operated at 220 kV.

Existing grid

The backbone of the grid in each island is the network of 220 kV transmission lines. These lines connect the larger cities and power users with the major power stations. Lower capacity 110 kV, 66 kV and 50 kV transmission lines connect smaller towns and cities and smaller power stations, and are connected to the 220 kV core grid through points of interconnection at major transmission substations. These stations include Otahuhu and Penrose in Auckland, Whakamaru, Wairakei and Bunnythorpe in the central North Island, Haywards in Wellington, Islington and Bromley in Christchurch, and Twizel and Benmore in the Waitaki Valley.

The grid today has ageing infrastructure, and increasing demand is placing significant loads on some parts of the network. Transpower is currently upgrading existing lines and substations to ensure supply security.

Investments in new transmission are now regulated by the Commerce Commission. In a news release in January 2012, the Commerce Commission reported that Transpower was planning to invest $5 billion over the next 10 years in upgrades of critical infrastructure.[45]

Since 2006, Transpower has spent nearly $2 billion reinforcing the supply into and around Auckland. A 400 kV-capable transmission line was completed in 2012, linking Whakamaru to Brownhill substation in Whitford, east of Auckland, with 220 kV cables linking Brownhill to Pakuranga. In 2014, a new 220 kV cable was commissioned between Pakuranga and Albany (via Penrose, Hobson Street and Wairau Road), forming a second high-voltage route between northern and southern Auckland.

HVDC Inter-Island

The HVDC Inter-Island scheme is New Zealand's only high voltage direct current (HVDC) system, and links the North and South Island grids together.

The link connects the South Island converter station at the Benmore Dam in southern Canterbury with the North Island converter station at Haywards substation in the Hutt Valley via a 610 km long overhead bipolar HVDC line with submarine cables across Cook Strait.

The HVDC link was commissioned in 1965 as a ±250 kV, 600 MW bipolar HVDC scheme using mercury-arc valve converters, and was originally designed to transfer surplus South Island hydroelectric power northwards to the more populous North Island. In 1976, the control system of the original scheme was modified to allow power to be sent in the reverse direction, from Haywards to Benmore.[46]

The HVDC link provides North Island consumers with access to the South Island's large hydro generation capacity, which may be important for the North Island during peak winter periods. For South Island consumers, the HVDC link provides access to the North Island's thermal generation capacity, which is important for the South Island during dry periods. Without the HVDC link, more generation would be needed in both the North and South Islands. In addition, the HVDC link is essential for the electricity market, as it allows generators in the North and South Islands to compete, putting downward pressure on prices and minimising the need to invest in costly new generating stations. The HVDC link also plays an important part in allowing renewable energy sources to be managed between the two islands.[47]

In 1992, the original mercury-arc equipment was paralleled to create a single pole (Pole 1), and a new thyristor-based pole (Pole 2) was commissioned alongside it. The transmission lines and submarine cables were also upgraded to double the link's maximum capacity to 1240 MW. The mercury-arc valve converter equipment was partially decommissioned in 2007, and fully decommissioned in August 2012. New thyristor converter stations (known as Pole 3) were commissioned on 30 May 2013 to replace the mercury arc converters. Further work to Pole 2 brought the link's capacity to 1200 MW by the end of the year.[48]

Distribution

Electricity from Transpower's national grid is distributed to local lines companies and large industrial users via 180 grid exit points (GXPs) at 147 locations. Large industrial companies, such as New Zealand Steel at Glenbrook, the Tasman Pulp and Paper Mill at Kawerau, and the Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter near Bluff, draw directly from Transpower substations and not the local lines companies' local grids.

Distribution of electricity to local consumers is the responsibility of one of 29 local line companies. Each company supplies electricity to a set geographic area based on the grid exit points they draw from.

The line companies are:

- Alpine Energy

- Aurora Energy

- Buller Electricity

- Centralines

- Counties Power

- Eastland Network

- Electra

- EA Networks

- Electricity Invercargill

- Horizon Energy Distribution

- The Lines Company

- MainPower

- Marlborough Lines

- Nelson Electricity

- Network Tasman

- Network Waitaki

- Northpower

- Orion

- OtagoNet

- The Power Company

- Powerco

- Scanpower

- Top Energy

- Unison Networks

- Vector

- Waipa Networks

- WEL Networks

- Wellington Electricity

- Westpower

In most areas, the local lines company operates a subtransmission network, connecting the GXP to zone substations. At the zone substation (or at the GXP if there is no subtransmission network), the voltage is stepped down to distribution voltage. Three-phase distribution is available in all urban and most rural areas. Single- or two-phase distribution utilising only two phases or single wire earth return systems are used in outlying and remote rural areas with light loads. Local pole-mounted or ground-mounted distribution transformers step-down the electricity from distribution voltage to the New Zealand mains voltage of 230/400 volts (phase-to-earth/phase-to-phase) for use in homes and businesses.

Subtransmission is typically at 33 kV, 50 kV, 66 kV or 110 kV, although parts of Auckland isthmus use 22 kV subtransmission. Distribution is typically at 11 kV, although some rural areas and high-density urban areas use 22 kV distribution, and some urban areas (e.g. Dunedin) use 6.6 kV distribution.

Isolated areas

New Zealand's national electricity network covers the majority of both the North and South Islands. There are also a number of offshore islands which are connected to the national grid. Waiheke Island, New Zealand's most populous offshore island, is supplied electricity via submarine cables between Maraetai and the island.[49][50] Arapaoa Island and d'Urville Island, both in the Marlborough Sounds, are supplied via overhead spans across Tory Channel and French Pass respectively.

However, many offshore islands and some parts of the South Island are not connected to the national grid and operate independent generation systems, mainly due to the difficulty of building lines from other areas. These places include:

- Great Barrier Island. The largest population in New Zealand without a reticulated electricity supply. Generation is from individual schemes for households or groups of households. A combination of renewable and non-renewable energy.

- Haast. The area around Haast and extending south to Jackson Bay is not connected to the rest of New Zealand. It operates from a hydroelectric scheme on the Turnbull River with diesel backup.

- Milford Sound. Electricity is generated via a small hydroelectric scheme operating off Bowen Falls with a diesel backup.

- Deep Cove, Doubtful Sound. The small community at Deep Cove at the head of Doubtful Sound operates off a hydro scheme, although during the construction of the second Manapouri Tailrace Tunnel a high voltage cable was installed connecting this tiny settlement with the Manapouri Power Station.

- Stewart Island / Rakiura. This island's power supply for a population of 300/400 people is entirely diesel generated. Renewable energy sources are limited, but they are being actively investigated in order to increase the sustainability of the island's power supply, and reduce the cost.

- Chatham Islands. Power on Chatham Island is provided by two 200 kW wind turbines that provide most of the power on the island while diesel generators provide the rest, with fuel brought from the mainland.

Many other schemes exist on offshore islands that have permanent or temporary habitation, mostly generators or small renewable systems. An example is the ranger / research station on Little Barrier Island, where twenty 175 watt photovoltaic panels provide the mainstay for local needs, with a diesel generator for backup.[51]

Consumption

In 2017, New Zealand consumed a total of 39,442 GWh of electricity. Industrial consumption made up 37% of that figure, agricultural consumption made up 6%, commercial consumption made up 24%, and residential consumption made up 31%.[1] There were just over 1,964,000 connections to the national electricity network in 2014, with 87% being residential connections.

| Category | Consumption (GWh) |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 2,535 |

| Industrial | 14,510 |

| Mining | 418 |

| Food Processing | 2,621 |

| Wood, Pulp, Paper and Printing | 2,692 |

| Chemicals | 821 |

| Basic Metals | 6,361 |

| Other sectors | 1,598 |

| Commercial and Transport | 9,448 |

| Residential | 12,197 |

| Total | 39,442 |

New Zealand's largest single electricity user is the Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter in Southland, which can demand up to 640 megawatts of power, and annually consumes around 5400 GWh. The smelter effectively has the Manapouri power station as a dedicated power generator to supply it.[52] Other large industrial users include the Tasman pulp and paper mill at Kawerau (175 MW demand), and New Zealand Steel's Glenbrook mill (116 MW demand).[53]

The other major consumers are the cities, with Auckland, the nation's largest city, demanding up to 1722 MW and consuming 8679 GWh in 2010–11.[49] Wellington, Christchurch, Hamilton and Dunedin are also major consumers, with other large demand centres including Whangarei-Marsden Point, Tauranga, New Plymouth, Napier-Hastings, Palmerston North, Nelson, Ashburton, Timaru-Temuka, and Invercargill.[53]

Major outages

- The 1998 Auckland power crisis involved a major failure of electricity distribution to the Auckland central business district.[54] Two 40-year-old cables connecting Penrose and Auckland's central business district failed in January to February 1998 during unseasonably hot weather, causing strain on the two newer remaining cables, which subsequently failed on 20 February 1998 and plunged central Auckland into darkness. The failure cost businesses NZ$300 million, and resulted in central Auckland being without electricity for 66 days until an emergency overhead line could reconnect the city – the longest peacetime blackout in history.[55]

- In June 2006, the seven-hour 2006 Auckland Blackout occurred when a corroded shackle at Otahuhu broke in strong winds and subsequently blacked out much of inner Auckland.[56]

- In October 2009, a three-hour blackout of northern Auckland and Northland occurred after a shipping container forklift accidentally hit the only major line supplying the region.[57]

- On Sunday 5 October 2014, a fire broke out at Transpower's Penrose substation. Major outages were experienced across central Auckland suburbs. The fire started in a cable joint in a medium voltage power cable. Over 75,000 businesses and households were affected. Power was fully restored by the afternoon of Tuesday 7 October.[58]

See also

- Energy in New Zealand

- List of power stations in New Zealand

- Renewable electricity in New Zealand

- National Grid (New Zealand)

- New Zealand electricity market

References

- Energy in New Zealand 2018, MBIE, 31 October 2018, ISSN 2324-5913

- "Energy Greenhouse Gas Emissions". MED. September 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- "Energy in New Zealand". MBIE. July 2014.

- New Zealand Historical Atlas – McKinnon, Malcolm (Editor); David Bateman, 1997, Plate 98

- "Phoenix Mine Hydro Electric Plant Site". New Zealand Historic Places Trust. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- P.G. Petchey (November 2006). "Gold and electricity – Archaeological survey of Bullendale, Otago" (PDF). Department of Conservation. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- New Zealand Historical Atlas; McKinnon, Malcolm (Editor); David Bateman, 1997, Plate 88

- the HON. WILLIAM FRASER, MINISTER OF PUBLIC WORKS (18 October 1912). "Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives PUBLIC WORKS STATEMENT". Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- "AtoJs Online — Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives — 1920 Session I — D-01 PUBLIC WORKS STATEMENT. BY THE HON. J. G. COATES, MINISTER OF PUBLIC WORKS". atojs.natlib.govt.nz. 1920. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Issacs, Nigel (December 2012). "Mastering meters" (PDF). BRANZ. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Background to Governance and Regulation, Electricity Authority". Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "New Zealand Commits to 90% Renewable Electricity by 2025". Renewable Energy World. 26 September 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Policy on Energy". National Party. 2008. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- Bradley, Grant (26 November 2007). "Big tick for wind as power of the future". The New Zealand Herald.

- "New Zealand to be carbon neutral by 2020" (PDF). Ecos 7. April–May 2007. p. 136. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- Parker, David (11 October 2007). "Energy strategy delivers sustainable energy system". Speech notes for launch of NZ Energy Strategy. New Zealand Government. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- "Biofuel Obligation Law Repealed". New Zealand Government. 17 December 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- "Thermal Ban Repealed". New Zealand Government. 16 December 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- "Light bulb ban ended". New Zealand Government. 16 December 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- MfE (16 December 2011). "Energy obligations". New Zealand Climate change information. Ministry for the Environment. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "Energy". New Zealand Climate change information. Ministry for the Environment. 16 December 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

The energy sector won't receive an allocation of NZUs because they'll be able to pass the costs of their ETS obligations on to their customers.

- "Labour's power plan 'political posturing'". 3 News NZ. 18 April 2013.

- "Opposition 'trying to disrupt share sales'". 3 News NZ. 19 April 2013.

- "Norman: Power plan will boost economy". 3 News NZ. 19 April 2013.

- "Norman: Contact shares continue to plummet". 3 News NZ. 19 April 2013.

- "Market Operation Service Providers". Electricity Authority. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- "Energy in New Zealand 2019". MBIE. 22 October 2019. ISSN 2324-5913.

- "MED Energy Sector Information: Waitaki River". MED. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- "Aviemore Dam". URS Corp. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- "Manapouri hydro station". Meridian Energy. 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "NZ Hosting Largest Geothermal Turbine at Nga Awa Purua". ThinkGeoenergy. 6 May 2010.

- "Development Potential". New Zealand Geothermal Association. Archived from the original on 2 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- MBIE (October 2018). "Energy in New Zealand 2018" (PDF). Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment. p. 49. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "New Zealand's Wind Farms". New Zealand Wind Energy Association. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- Bradley, Grant Bradley, Grant (7 June 2011). "Wellington winds too windy for wind farm". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Huntly Power Station". Genesis Energy. Archived from the original on 25 May 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- "Installed distributed generation trends". Electricity Authority.

- "Tidal power rides wave of popularity". TVNZ. 2 December 2007.

- "AWATEA newsletter" (PDF). 10 February 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Aotearoa Wave and Tidal Energy Association".

- "Marine Energy". Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority.

- "Nuclear Energy Prospects in New Zealand". World Nuclear Association. April 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987 – New Zealand Legislation". Parliamentary Counsel Office. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- "A Guide to Transpower 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Commerce Commission finalises input methodology for approving Transpower's national grid spending". Commerce Commission. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Taylor, Peter (1990). White Diamonds North: 25 Years' Operation of the Cook Strait Cable 1965–1990. Wellington: Transpower. pp. 109 pages. ISBN 0-908893-00-0.

- "2012 Annual Planning Report: Chapter 6 – Grid Backbone" (PDF). Transpower. March 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- https://www.transpower.co.nz/news/new-hvdc-pole-3-commissioned

- "Electricity Asset Management Plan 2012 – 2022" (PDF). Vector Limited. April 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Why Waiheke Island should have a wind farm? – Waiheke Initiative for Sustainable Energy". 11 February 2011.

- "New Zealand Energy Quarterly, March 2010". 16 June 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Bennett, Adam (3 October 2007). "Meridian boss hails deal with smelter". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- "Annual Planning Report 2012". Transpower New Zealand Limited. April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Johnston, Martin (16 April 2018). "A crisis recalled: The power cuts that plunged the Auckland CBD in darkness for five weeks". The New Zealand Herald.

- Guinness World Records 2011. London: Guinness World Records. 2010. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-904994-57-2.

- Field, Michael; Walters, Laura (6 October 2014). "Auckland's history of power cuts". Stuff.

- NZPA/ONE News (30 October 2009). "Forklift sparks blackout for thousands". Television New Zealand. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- Electricity Authority. "Electricity Authority Review of October 2014 Power Outage".

Further reading

- Martin, John E, ed. (1998). People, Power and Power Stations: Electric Power Generation in New Zealand 1880–1990 (Second ed.). Wellington: Bridget Williams Books Ltd and Electricity Corporation of New Zealand. pp. 356 pages. ISBN 0-908912-98-6.

- Reilly, Helen (2008). Connecting the Country: New Zealand's National Grid 1886–2007. Wellington: Steele Roberts. ISBN 978-1-877448-40-9.

External links

- Energy and Resources (New Zealand Government, portfolio website)

- Electricity Networks Association represents the network companies (line companies)