Great Barrier Island

Great Barrier Island (Māori: Aotea) lies in the outer Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand, 100 kilometres (62 mi) north-east of central Auckland. With an area of 285 square kilometres (110 sq mi) it is the sixth-largest island of New Zealand and fourth-largest in the main chain. Its highest point, Mount Hobson, is 627 metres (2,057 ft) above sea level.[3] The local authority is the Auckland Council.

| Aotea (Māori) Nickname: The Barrier | |

|---|---|

Kaitoke Beach in the east of Great Barrier Island. The "White Cliffs" can be seen in the front right. | |

Great Barrier Island | |

| Geography | |

| Location | North Island |

| Coordinates | 36°12′S 175°25′E |

| Area | 285 km2 (110 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 621 m (2,037 ft)[1][2] |

| Highest point | Mount Hobson or Hirakimata |

| Administration | |

New Zealand | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 930 (2018) |

| Pop. density | 3/km2 (8/sq mi) |

The island was initially exploited for its minerals and kauri trees and saw only limited agriculture. In 2013, it was inhabited by 939 people,[4] mostly living from farming and tourism.[5] The majority of the island (around 60% of the total area) is administered as a nature reserve by the Department of Conservation.[3] In 2009 the island atmosphere was described as being "life in New Zealand many decades back".[6]

Geography

With an area of 285 square kilometres (110 sq mi), Great Barrier Island is the sixth-largest island in New Zealand after the South Island, the North Island, Stewart Island/Rakiura, Chatham Island, and Auckland Island. The highest point, Mount Hobson or Hirakimata, is 627 metres (2,057 ft) above sea level.

Great Barrier is surrounded by several smaller islands, including Kaikoura Island, Rakitu Island, Aiguilles Island and Dragon Island. A number of islands are located in Great Barrier bays, including Motukahu Island, Nelson Island, Kaikoura Island, Broken Islands, Motutaiko Island, Rangiahua Island, Little Mahuki Island, Mahuki Island and Junction Islands.

The island's European name stems from its location on the outskirts of the Hauraki Gulf. With a maximum length (north-south) of some 43 kilometres (27 mi), it and the Coromandel Peninsula (directly to its south) protect the gulf from the storms of the Pacific Ocean to the east. Consequently, the island boasts highly contrasting coastal environments. The eastern coast comprises long, clear beaches, windswept sand-dunes, and heavy surf. The western coast, sheltered and calm, is home to hundreds of tiny, secluded bays which offer some of the best diving and boating in the country. The inland holds several large and biologically diverse wetlands, along with rugged hill country (bush or heath in the more exposed heights), as well as old-growth and regenerating kauri forests.

Etymology

The island received its European name from Captain Cook because it acts as a barrier between the Pacific Ocean and the Hauraki Gulf.[3] The Māori name is Aotea.[7]

Entrance to the Hauraki Gulf is via two channels, one on each side of the island. Colville Channel separates the southernmost point, Cape Barrier, from Cape Colville at the northern tip of the Coromandel Peninsula to the south, Cradock Channel from the smaller Little Barrier Island to the west. The island protects the gulf from the ocean surface waves and the currents of the South Pacific Gyre. It is not a sandbar barrier, often defined as the correct use of the term.

History and culture

Aotea is the ancestral land of Ngāti Rehua Ngātiwai ki Aotea who are the tangata whenua (people of the land) and mana whenua (territorial land rights holders) of Aotea. Ngāti Rehua have occupied Aotea since the 17th century after conquering Aotea from people of Ngāti Manaia and Kawerau descent.

Local industries

Mining

Early European interest followed discovery of copper in the remote north, where New Zealand's earliest mines were established at Miners Head in 1842. Traces of these mines remain, largely accessible only by boat. Later, gold and silver were found in the Okupu / Whangaparapara area in the 1890s, and the remains of a stamping battery on the Whangaparapara Road are a remainder of this time. The sound of the battery working was reputedly audible from the Coromandel Peninsula, 20 km away.[3][8]

In early 2010, a government proposal to remove 705 ha of land on the Te Ahumata Plateau (called "White Cliffs" by the locals) from Schedule 4 of the Crown Minerals Act, which gives protection from the mining of public land, was widely criticised. Concerns were that mining for the suspected $4.3 billion in mineral worth in the area would damage both the conservation land as well as the island's tourism economy. Locals were split on the project, some hoping for new jobs.[8] If restarted, mining at White Cliffs would occur in the same area it originally proliferated on Great Barrier. The area's regenerating bushland still holds numerous semi-collapsed or open mining shafts where silver and gold had been mined.[8]

Kauri logging

The kauri logging industry was profitable in early European days and up to the mid-20th century. Forests were well inland, with no easy way to get the logs to the sea or to sawmills. Kauri logs were dragged to a convenient stream bed with steep sides and a driving dam was constructed of wood, with a lifting gate near the bottom large enough for the logs to pass through. When the dam had filled, which might take up to a year, the gate was opened and the logs above the dam were pushed out through the hole and swept down to the sea.[9] The logging industry cut down large amounts of old growth, and most of the current growth is younger native forest (around 150,000 kauri seedlings were planted by the New Zealand Forest Service in the 1970s and 1980s) as well as some remaining kauri in the far north of the island.[3][5] Much of the island is covered with regenerating bush dominated by kanuka and kauri.[10]

Other industries

Great Barrier Island was the site of New Zealand's last whaling station, at Whangaparapara, which opened in 1956, over a century after the whaling industry peaked in New Zealand, and closed due to depletion of whaling stocks and increasing protection of whales by 1962.[3] Some remains can be visited.

Another small-scale industry was kauri gum digging, while dairy farming and sheep farming have tended to play a small role compared to the usual New Zealand practice. A fishing industry collapsed when international fish prices dropped.[8] Islanders are generally occupied in tourism, farming or service-related industries when not working off-island.[8]

Shipwrecks

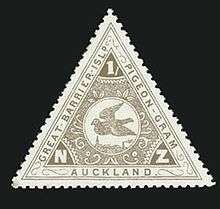

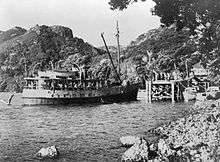

The remote north was the site of the sinking of the SS Wairarapa around midnight of 29 October 1894. This was one of New Zealand's worst shipwrecks, with about 140 lives lost, some of them buried in two beach grave sites in the far north.[3] As a result, a Great Barrier Island pigeon post service was set up, the first message being flown on 14 May 1897. Special postage stamps were issued from October 1898 until 1908, when a new communications cable was laid to the mainland, which made the pigeon post redundant.[11] Another major wreck lies in the far southeast, the SS Wiltshire.[3]

Nature reserves

Over time, more and more of the island came under the stewardship of the Department of Conservation (DOC) or its predecessors. Partly this was land that had always belonged to the Crown, while other parts were sold or donated like the more than 10% of the island (located in the northern bush area, with some of the largest remaining kauri forests) that was gifted to the Crown by farmer Max Burrill in 1984.[3] DOC has created a large number of walking tracks through the island, some of which are also open for mountain biking.[10]

The island is free of some of the more troublesome introduced pests that plague the native ecosystems of other parts of New Zealand. While wild cats, dogs, feral pigs, black rats, Polynesian rats and mice are present, there are no known populations of possums, mustelids (weasels, stoats or ferrets), hedgehogs, brown rats or deer, thus being a relative haven for native bird and plant populations. Feral goats were eradicated in 2006.[12] Rare animals found on the island include brown teal ducks, black petrel seabirds and kaka parrots.[3][10]

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 867 | — |

| 2013 | 933 | +1.05% |

| 2018 | 930 | −0.06% |

| Source: [15] | ||

The statistical area of Barrier Islands, which includes Little Barrier Island although that has no permanent inhabitants, had a population of 930 at the 2018 New Zealand census, a decrease of 3 people (-0.3%) since the 2013 census, and an increase of 63 people (7.3%) since the 2006 census. There were 531 households. There were 501 males and 429 females, giving a sex ratio of 1.17 males per female. The median age was 52.6 years, with 138 people (14.8%) aged under 15 years, 90 (9.7%) aged 15 to 29, 477 (51.3%) aged 30 to 64, and 225 (24.2%) aged 65 or older.

Ethnicities were 91.3% European/Pākehā, 20.6% Māori, 2.6% Pacific peoples, 1.3% Asian, and 1.9% other ethnicities (totals add to more than 100% since people could identify with multiple ethnicities).

The proportion of people born overseas was 18.4%, compared with 27.1% nationally.

Although some people objected to giving their religion, 62.6% had no religion, 24.5% were Christian, and 3.9% had other religions.

Of those at least 15 years old, 144 (18.2%) people had a bachelor or higher degree, and 144 (18.2%) people had no formal qualifications. The median income was $21,300. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 279 (35.2%) people were employed full-time, 168 (21.2%) were part-time, and 57 (7.2%) were unemployed.[15]

Settlements

The population is primarily in coastal settlements such as Tryphena, the largest settlement in Tryphena Harbour, at the southern end. Other communities are Okupu, Whangaparapara, Port Fitzroy, Claris and Kaitoke. There is no central power, and houses require their own generators.[5] There is also extensive use of solar water heating, solar panels for electricity and wind-powered generators.

The population swells substantially during the main holiday seasons, though it is still not a major tourist destination due to its relative remoteness.

From the end of February 2007, the island was seen around the world as the setting for the BBC One reality show Castaway, which was filmed there for three months.

Transport

There are airfields at Claris and Okiwi. Barrier Air and Fly My Sky operate services from Auckland Airport, and North Shore Aerodrome. Sunair operates from Ardmore Airport in Auckland to/from Great Barrier Island, Tauranga and Whitianga. Flight time is approximately 35 minutes from Auckland.

SeaLink operates a fast ferry over the summer months and a passenger, car and freight ferry. These operate from Wynyard Wharf in Auckland city to Tryphena (several times weekly) and Port Fitzroy on Wednesdays. Sailing time is approximately four and a half hours.

Other travel options: Barrier Express fast ferry from Sandspit or Auckland. Flight Hauraki, Christian Aviation, Auckland Seaplanes, Heletranz, Oceania Helicopters.

Civic institutions

Institutions and services are primarily provided by the Auckland Council, the local authority. Services and infrastructure like roads and the wharves at Tryphena and Whangaparapara are subsidised, with the island receiving about $4 in services for every $1 in rates.[8] The Port FitzRoy wharf is owned by the North Barrier Residents and Ratepayers Association.

There are three primary schools at Mulberry Grove, Tryphena; Kaitoke and Okiwi, but no secondary schools, so students either leave for schooling on the mainland or receive their education via the New Zealand Correspondence School. The lack of secondary schooling has been cited as one of the reasons for a slow exodus of long-term resident families.[16]

As part of Auckland the rules governing daily activities and applicable standards for civic works and services exists, shared with some of the other inhabited islands of the Hauraki Gulf. Driving rules are the same as for the rest of NZ and registration and a Warrant of Fitness are required for all vehicles. For example, every transport service operated solely on the island, the Chatham Islands, or Stewart Island/Rakiura is exempt from section 70C of the Transport Act 1962, the requirements for drivers to maintain driving-hours logbooks. Drivers subject to section 70B must nevertheless keep records of their driving hours in some form.[17]

Rules governing dog control are the same as for Auckland. Dogs must be kept on a lead in all public places.

Notable residents

- Fanny Osborne (1852–1934), artist[18]

See also

References

- "Information about Great Barrier Island, New Zealand - Great Barrier Island Tourism". www.greatbarrierislandtourism.co.nz.

- "Mount Hobson, Auckland - NZ Topo Map". Land Information New Zealand. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Great Barrier Island Aotea page on the DOC website (from the Department of Conservation. Accessed 2008-06-04.)

- 2013 Census QuickStats about a place : Great Barrier Island Local Board Area from Statistics New Zealand.

- Great Barrier Island Archived 2010-12-25 at the Wayback Machine (from the Auckland City Council website)

- Vass, Beck (18 January 2009). "Great Barrier - island that tough times forgot". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- One of several possible translations of Aotea is "white cloud". However some traditions give Aotea as the name of Kupe's canoe: see Aotearoa.

- Dickison, Michael (23 March 2010). "Great Barrier locals at odds over mining plan". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- Mahoney, Paul (1 March 2009). "Bush trams and other log transport - Moving kauri: dams and rafting". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Great Barrier Island Aotea brochure, Front (from the DOC. Accessed 2008-06-04.)

- Centenary of Pigeon Post Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine (from the New Zealand Post website. Accessed 2008-06-04.)

- "Feral goats to be eradicated on Waiheke". Auckland Council. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Te Kāhui Māngai directory". tkm.govt.nz. Te Puni Kōkiri.

- "Māori Maps". maorimaps.com. Te Potiki National Trust.

- "Statistical area 1 dataset for 2018 Census". Statistics New Zealand. March 2020. Barrier Islands (111800). 2018 Census place summary: Barrier Islands

- Rush, Paul (6 January 2010). "Great Barrier: Barrier break away". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Unknown article name - New Zealand Gazette, Thursday 14 August 2003

- Mackle, Tony. "Fanny Osborne". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Barrier Island. |

- Photographs of Great Barrier Island held in Auckland Libraries' heritage collections.

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Great Barrier Island. |