Egyptian cheese

Egyptian cheese (Egyptian Arabic: جبنة gebna pronounced [ˈɡebnæ]) has a long history, and continues to be an important part of the Egyptian diet. There is evidence of cheese-making over 5,000 years ago in the time of the First Dynasty of Egypt. In the Middle Ages the city of Damietta was famous for its soft, white cheese. Cheese was also imported, and the common hard yellow cheese, rumi takes its name from the Arabic word for "Roman". Although many rural people still make their own cheese, notably the fermented mish, mass-produced cheeses are becoming more common. Cheese is often served with breakfast, and is included in several traditional dishes, and even in some desserts.

History

Ancient Egypt

Cheese is thought to have originated in the Middle East. The manufacture of cheese is depicted in murals in Egyptian tombs from 2,000 BC. Two alabaster jars found at Saqqara, dating from the First Dynasty of Egypt, contained cheese.[1] These were placed in the tomb about 3,000 BC.[2] They were likely fresh cheeses coagulated with acid or a combination of acid and heat. An earlier tomb, that of King Hor-Aha may also have contained cheese which, based on the hieroglyphic inscriptions on the two jars, appear to be from Upper and Lower Egypt.[3] The pots are similar to those used today when preparing mish.[4]

Cottage cheese was made in ancient Egypt by churning milk in a goatskin and then straining the residue using a reed mat. The Museum of Ancient Egyptian Agriculture displays fragments of these mats.[5]

In the 3rd century BC there are records of imported cheese from the Greek island of Chios, with a twenty-five percent import tax being charged.[6]

Middle Ages

According to the medieval philosopher Al-Isra'ili, in his day there were three types of cheese: "a moist fresh cheese which was consumed on the same day or close to it; there was an old dry cheese; and there was a medium one in between." The first would have been unripened cheese made locally from sour milk, which may or may not have been salted. The old dry cheeses would have often been imported, and were cheeses ripened by rennet enzymes or bacteria.[7] The nature of the "medium" cheese is less certain, and may have referred to preserved fresh cheeses, evaporated milk or cheese similar to Indian paneer, where the addition of vegetable juices makes the milk coagulate.[8]

Medieval Egyptian cheese mostly used buffalo or cows' milk, with less use of goat and sheep milk than in other countries of the region. Damietta on the Mediterranean coast was the primary area where cheese was made for consumption in other parts of the country. Damietta was well known not just for its buffaloes but also for its Khaysiyya cows, from which Kaysi cheese was made.[9] Khaysi cheese is mentioned as early as the eleventh century A.D. A fifteenth century author describes the cheese being washed, which may imply that it was salted in brine.[10] It may therefore have been an ancestor of modern Dumyati cheese, produced today in the Damietta district.[11] Fried cheese (جبنة مقلية gebna maqleyya) was a common food in Egypt in the Middle Ages, cooked in oil and served with bread by street vendors.[11] Fried cheese was eaten by both poor and rich, and was considered a delicacy by some of the Mamluk sultans.[12]

A 17th-century writer described mishsh as the "blue qarish cheese which was kept for so long that it cut off the mouse's tail with its burning sharpness and the power of its saltiness". The Egyptian peasants ate this cheese with bread, leeks, or green onions as a staple part of their diet. It seems that the mishsh made and eaten by country people today is essentially the same cheese.[13] The Egyptians also imported cheese from Sicily, Crete and Syria in the Middle Ages.[9]

Recent years

Production of pickled cheeses rose from 171,000 tonnes in 1981 to 293,000 tonnes in 2000, almost all consumed locally. Imports of cheese to Egypt peaked at 29,000 tonnes in 1990, but with establishment of modern factories the volume of imports had dropped to under 1,000 tonnes by 2002.[14] Between 1984 and 2007 production of cheese of all types in Egypt rose steadily from about 270,000 tonnes to over 400,000 tonnes.[15] In 1991 roughly half of the cheese was still made using traditional methods in rural areas, and the other half was made using modern processes.[16] The common Domiati cheese was being manufactured by private dairies using small milk batches of 500 kilograms (1,100 lb), and in large government plants in five tonne batches. The government owned Misr Milk and Food Co. had nine plants with an annual capacity of 13,000 to 150,000 tonnes of dairy products.[17]

Annual consumption of pickled cheeses was estimated at 4.4 kilograms (9.7 lb) in 2000.[14] In 2002 it was estimated that more than one third of Egyptian milk production was used in making traditional pickled cheeses or ultrafiltered feta-type cheeses.[18] The domiati cheese now contains less buffalo milk than in the past. The fat from cows' milk is replaced in part by vegetable oils to reduce cost and retain the white color expected by consumers. Various other changes have been introduced such as mandatory heat treatment of the milk, but manufacturers have striven to retain the familiar taste, texture and appearance of the cheeses.[14]

Cuisine

Cheese is often served with breakfast in Egypt, along with bread, jams and olives. Various types of soft, white cheeses (categorically referred to as gebna bēḍa) and gebna rūmi may be eaten in ēish fīno, a small baguette, or with ēish baladi, a flatbread that forms the backbone Egyptian cuisine.[19] White cheeses and mish are also often served at the start of a multi-course meal alongside various appetizers, or muqabilat, and bread.

Fiteer is a flaky filo pastry with a stuffing or topping that may include white cheese and peppers, ground meat, egg, onions and olives.[20] Sambusak is a flaky pastry that may be stuffed with cheese, meat or spinach.[21]

Qatayef, a dessert commonly served during the month of Ramadan, is of Fatimid origin. It is often prepared by street vendors in Egypt.[22] Qatayef are pancakes stuffed with nuts or soft cheese, deep fried and covered in syrup. In Egypt, Ibn al-Qata'if, or "son of the pancake maker" is an Egyptian Jewish family name.[23]

Cheese varieties

| English | Arabic | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Areesh | قريش | A type of white, soft, lactic cheese made from laban rayeb.[24] |

| Baramily | براميلى | A type of white cheese aged in barrels, the name translates to barrel cheese in English. |

| Domiati | دمياطى | A soft white cheese usually made from cow or buffalo milk. It is salted, heated, coagulated using rennet and then ladled into wooden molds where the whey is drained away for three days. The cheese may be eaten fresh, or stored in salted whey for up to eight months, then matured in brine.[11] Domiati cheese accounts for about three quarters of the cheese made and consumed in Egypt.[25] The cheese takes its name from the city of Damietta and is thought to have been made as early as 332 BC.[26] |

| Halumi | حلومى | Similar to Cypriot halloumi, yet a different cheese. It may be eaten fresh or brined and spiced. The name comes from the Coptic word for cheese, "halum". |

| Istanboly | اسطنبولى | A type of white cheese made from cow or buffalo milk, similar to feta cheese. |

| Mish | مش | A sharp and salty product made by fermenting cheese for several months in salted whey. It is an important part of the diet of farmers.[27] Mish is often made at home from areesh cheese.[28] Products similar to mish are made commercially from different types of Egyptian cheese such as domiati or rumi, with different ages. |

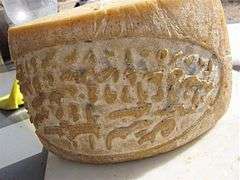

| Rumi | رومى | A hard, bacterially ripened variety of cheese.[29] It belongs to the same family as Pecorino Romano and Manchego.[30] It is salty, with a crumbly texture, and is sold at different stages of aging.[27] |

See also

- List of cheeses – list of cheeses by place of origin

- Egyptian cuisine – National cuisine of Egypt

References

Citations

- Lucas 2003, p. 383.

- Kindstedt 2012, p. 34.

- Kindstedt 2012, p. 35.

- Lambert 2001, p. 20.

- Mehdawy & Hussein 2010, p. 41.

- Kindstedt 2012, p. 74.

- Lewicka 2011, p. 230.

- Lewicka 2011, p. 231.

- Lewicka 2011, p. 235.

- Lewicka 2011, p. 236.

- Lewicka 2011, p. 237.

- Lewicka 2011, p. 238.

- Lewicka 2011, p. 242.

- Tamime 2008, p. 140.

- Egypt Dairy, Cheese Production by Year.

- Robinson & Tamime 1991, p. 181.

- Robinson & Tamime 1991, p. 161.

- Tamime 2008, p. 139.

- Russell 2013, p. 288.

- Fodor's 2011, p. 55.

- Fodor's 2011, p. 34.

- Zahra 1999, p. 290.

- Marks 2010, p. 129.

- Robinson & Tamime 1991, p. 183.

- El-Baradei, Delacroix-Buchet & Ogier 2007, p. 1248.

- Robinson & Tamime 1991, p. 160.

- African Cheese: Egypt.

- Robinson & Tamime 1991, p. 190.

- Fox et al. 2004, p. 20.

- Fox et al. 2004, p. 11.

Sources

- "African Cheese: Egypt". ifood.tv. FutureToday Inc. Archived from the original on 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- Aldosari, Ali (2013). Middle East, western Asia, and northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1107. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2. Retrieved 2013-04-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eekhof-Stork, Nancy (1976). The world atlas of cheese. Paddington Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8467-0133-0. Retrieved 14 April 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Egypt Dairy, Cheese Production by Year". IndexMundi. Retrieved 2013-04-15.

- El-Baradei, Gaber; Delacroix-Buchet, Agnès; Ogier, Jean-Claude (February 2007). "Biodiversity of Bacterial Ecosystems in Traditional Egyptian Domiati Cheese". Appl Environ Microbiol. 73 (4): 1248–1255. doi:10.1128/AEM.01667-06. PMC 1828670. PMID 17189434.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fodor's (2011-03-15). Fodor's Egypt, 4th Edition. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4000-0519-2. Retrieved 2013-04-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fox, Patrick F.; McSweeney, Paul L.H.; Cogan, Timothy M.; Guinee, Timothy P., eds. (2004-08-04). Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology: Major Cheese Groups. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-050094-2. Retrieved 2013-04-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Helou, Anissa (1998). Lebanese Cuisine. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0312187351.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Jibneh Arabieh". Cheese.com. Worldnews, Inc. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- Kindstedt, Paul (2012). Cheese and culture. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-60358-412-8. Retrieved 2013-04-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambert, Paula (2001-01-09). The Cheese Lover's Cookbook & Guide: Over 100 Recipes, with Instructions on How to Buy, Store, and Serve All Your Favorite Cheeses. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-1328-8. Retrieved 2013-04-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewicka, Paulina (2011-08-25). Food and Foodways of Medieval Cairenes: Aspects of Life in an Islamic Metropolis of the Eastern Mediterranean. BRILL. p. 230. ISBN 978-90-04-19472-4. Retrieved 2013-04-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lucas, A. (2003-04-01). Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries 1926. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-5141-3. Retrieved 2013-04-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marks, Gil (2010-11-17). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-544-18631-6. Retrieved 2013-04-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mehdawy, Magda; Hussein, Amr (2010). The Pharaoh's Kitchen: Recipes from Ancient Egypt's Enduring Food Traditions. American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-310-4. Retrieved 2013-04-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "PATLIJAN BOEREG (An Egyptian Eggplant Specialty)". RecipeSource. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- Richardson, Dan (2003). The Rough Guide to Egypt. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-050-3. Retrieved 2013-04-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, R. K.; Tamime, Adnan Y. (1991-06-01). Feta and Related Cheeses. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85573-278-0. Retrieved 2013-04-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Russell, Mona L. (2013-01-31). Egypt. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-233-3. Retrieved 2013-04-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sindell, Cheryl (March 1993). Not "Just a salad": how to eat well and stay healthy when eating out. Pharos Books. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-88687-733-0. Retrieved 2013-04-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2004-11-29). Ency Kitchen History. Taylor & Francis. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-203-31917-8. Retrieved 2013-04-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tamime, A. Y. (2008-04-15). Brined Cheeses. John Wiley & Sons. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-4051-7164-9. Retrieved 2013-04-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zahra, Nadia Abu (1999). The Pure and Powerful: Studies in Contemporary Muslim Society. Garnet & Ithaca Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-86372-269-1. Retrieved 2013-04-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)