Prince Saunders

Prince Saunders (1775–1839) was an African American teacher, scholar, diplomat, and author who different sources say was born in either Lebanon, Connecticut, or Thetford, Vermont. During his life, Saunders helped set up schools for African Americans in Massachusetts and also in Haiti, for King Henri Christophe. During his time in Haiti, Saunders also penned the Haytian Papers, which were a translation of the Haitian laws with his commentary. He was a proponent of black emigration to Haiti, where he became a naturalized citizen.[1] Because of his influence in establishing schools for African Americans, Saunders was one of the most significant black educators in the early 19th century in the United States and Haiti. He lived his last days in Port-au-Prince, where he died in 1839.

Prince Saunders | |

|---|---|

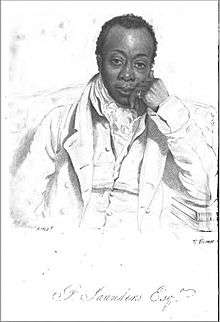

Prince Saunders' portrait as it appears in the Haytian Papers | |

| Born | Prince Saunders 1775 |

| Died | 1839 (aged 63–64) |

| Nationality | Haitian, American |

| Alma mater | Dartmouth College |

| Occupation | Educator, reformer |

Early life

In 1784, Saunders was baptized as a Christian, which is the only glimpse we have into his childhood. Saunders grew up in the home of George Oramel Hinckley, a prominent white lawyer in New England.[2] Being brought up under Hinckley, Saunders received an education that was equal to many highly educated whites at this time. Many of his studies were based on Bible and Christian teachings, which would be reflected later on in his life.

Early education and School

By the time Saunders was 21, he was already a teacher in Colchester, Connecticut, at the local school for African Americans.[2] From 1807 until 1808, Saunders attended Moor's Charity School at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire under the sponsorship of Hinckley. While attending the school, Saunders gained the respect of Dartmouth President John Wheelock. Wheelock suggested that Saunders should become a school teacher at the free African American school in Boston.

With Wheelock's recommendation, Saunders earned the position of educator at the school, which was run by William Ellery Channing, a Unitarian minister in Boston. Most of the students at the school came from "Nigger Hill", a poor neighborhood in Boston, where the majority of the city's African Americans lived.[3]

Around the same time that he began teaching in Boston, Saunders also became involved in Masonic lodges. In 1809, Saunders was initiated into the African Masonic Lodge in Boston. Two years later, in 1811, Master George Middleton made Saunders the secretary of the lodge.[4]

Career

In 1815, Saunders furthered African American education in Boston, when he successfully persuaded a white, merchant, philanthropist, Abiel Smith, into issuing a grant to help support his education cause.[5] Saunders was able to get Smith to bestow revenue of stocks for the education of African Americans in reading, writing and arithmetic. Though Smith died in 1816, his contributions continued to fund education for African Americans, which culminated in the founding of the Abiel Smith School in 1835.[3]

Later in 1815, Saunders sailed to Britain with Thomas Paul, seeking legitimacy for Black American freemasonry, known as the Prince Hall Masons and to reinforce the links with the British abolitionist community. In London Saunders met the renown abolitionist duo, William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson with whom he developed a life-long friendship.[4] They persuaded Saunders to assist Haiti and provide King Henri Christophe with educational leadership.[6]

Emigration to Haiti

Upon Saunders' arrival to Haiti, he began working as an advisor for Christophe. Saunders impressed the king by his striking "Negro" features, manners, and remarkable education.[7] Because Christophe considered Saunders to be the face of black accomplishment, Saunders later became Christophe's official courier.

During his reign as king in Haiti, Christophe had to battle with mulatto domination and the influence of former French settlers on the island.[7] The French believed that intellectually, blacks were inferior to their white counterparts. To counter this, Christophe wanted to set up a school system in Haiti, which he believed would disprove the French theory. To Christophe, Saunders was the perfect man for the job, as not only was he adept in running schools and teaching, but he was also black, which meant a successful school system would reflect positively for the blacks on the island.

Saunders made several trips back and forth between Haiti and London. On those trips, Saunders brought back smallpox vaccination, in addition to four Lancastrian teachers that helped in creating the Royal College of Haiti, in Cape Henry. In return, Christophe gave the schools furnishing that was equivalent to what could be found in England at the time.[8]

Notable works

Haytian Papers[9]

While in Haiti, Saunders wrote the Haytian Papers, which was then published in London. The book was his translation of the laws of Haiti, and his commentary on those laws. What interested Saunders was the value of the Haitian history that formed the laws, as their histories were not written by black Haitians.[10] The commentary of decrees from Christophe allowed for insight into the way in which the Haitian government was run.

In the Haytian Papers, Saunders applauds the principles of the government under King Christophe, who wanted to prove that black people were just as intelligent as white people by creating an educational system on Haiti. This work is based on Christophe's Code Rural, which openly endorsed a system of forced labor, which went against the Haitian Revolution's goal of ending oppression. According to Christophe, the system of forced labor would exponentially increase farm production.

Prince Saunders authored the Haytian Papers for the British people, who had a negative view of Haiti, "in order to give them some more correct information" of the Haitian government and to throw light on the new and much improved condition of all classes of society in that kingdom. He believed it was only fair and necessary that the feelings of the Haitians should be made evident. The history of Haiti had previously have been written not by the Haitians themselves but by white Europeans who did not understand the law. The Haytian Papers were from the views of colored people without a "drop of white European blood in them."[11]

Address before the Pennsylvania Augustine Society

In 1818, Saunders delivered "An address before the Pennsylvania Augustine Society." In his address, Saunders advocated for a Christian education for blacks, which he believed was "more transcendently excellent in that more elevated scene of human destination to which we are hastening." Saunders also argued that improvements in the lives of African Americans, intellectually, morally, and religiously, "depend on the future elevation of their standing, in the social, civil, and ecclesiastical community."[12]

The People of Haiti and Plan of Emigration

During his time in Boston, Saunders met Thomas Paul, who was the founder of America's Black Baptist Church.[3] Both Saunders and Paul became activists in Massachusetts for the promoting of free black emigration from the United States due to racial discrimination. After Saunders' return from Haiti to America, he began to advocate Haiti as the ideal location for emigration of blacks from America. During this time he gave his speech, The People of Haiti and Plan of Emigration.

In the same year as the address to the Augustine Society, Saunders gave a speech at the American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and Improving the Condition of the African Race,[13] that promoted the ending of slavery and the betterment of the lives of African Americans. In his speech, Saunders advocated not only for the ending of slavery and inequalities based on race, but also for the emigration of blacks to Haiti.

Having spent time in Haiti working under King Christophe, Saunders became familiar with the country, which led him to see Haiti as a viable option for black emigration. Saunders saw Haiti as "the paradise of the New World", which he drew from "its situation, extent, climate, and fertility peculiarly suited to become an object of interest and attention."[14]

Social Life

During his time, Saunders was known for his intelligence and eloquence, evidence of his strong educational upbringing. He was known to impress people with his knowledge from his education – an education that was rare for an African American at the time. Charles Robert Leslie recalled one instance of Prince Saunders, in his book, Autobiographical Recollections.

I was taken by my friend, Dr. Francis, of New York, to one of Sir Joseph Banks's conversazioni. The old gentlemen received his company sitting (being very gouty), in his library, at one end of which hung a portrait of Captain Cook. The room was filled with the most eminent scientific and literary men, but Prince Saunders, the coal black Boston negro, was the great man of the evening; a negro too of the most moderate abilities. Everybody asked to be presented to "His Highness." I got near to hear what passed in his circle, and a gentleman, with a star and ribbon, said to him, "What surprises me is that you speak English so well." Saunders, who had never spoken any other language in his life, bowed, and smiled acceptance of the compliment.

— Charles Robert Leslie, Autobiographical Recollections, 1860

While in England, Saunders also earned a celebrity status among the social elite. Though Prince was his given Christian name, it was assumed by the English people that the name indicated a standing of African nobility. This was partially due to the fact that Saunders never corrected anyone who referred to him as such. Because of his "nobility standing", Saunders was a fixture in the English social circles, especially with The Countess of Cork.[15]

Later life

After Christophe's death, biographer Harold Van Buren Voorhis claimed that Saunders was made Attorney General by Haiti's new president, Jean-Pierre Boyer.[4] Saunders then lived most of his remaining life in Haiti, before he died in Port-au-Prince, in 1839.

See also

References

- Hector, Cary; Jadotte, Hérard, eds. (1991). Haiti and the post-Duvalier : continuities and ruptures, Volume 2. p. 386. ISBN 9782920862531. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Arthur White, "Prince Saunders: An Instance of Social Mobility Among Antebellum New England Black," The Journal of Negro History 40, no. 4 (1975), 526.

- Arthur White, "Prince Saunders: An Instance of Social Mobility Among Antebellum New England Black," The Journal of Negro History 40, no. 4 (1975), 527.

- Harold van Buren Voorhis, Negro Masonry in the United States (Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing, 1995), 113.

- Arthur White, "The Black Leadership Class and Education in Antebellum Boston," The Journal of Negro Education 42, no. 4 (1973), 510.

- Conerly, Jennifer Yvonne (2013-05-18). "Your Majesty 's Friend": Foreign Alliances in the Reign of Henri Christophe (Masters' Thesis). University of New Orleans. p. 5.

- Arthur White, "Prince Saunders: An Instance of Social Mobility Among Antebellum New England Black," The Journal of Negro History 40, no. 4 (1975): 528.

- Arthur White, "Prince Saunders: An Instance of Social Mobility Among Antebellum New England Black," The Journal of Negro History 40, no. 4 (1975): 529.

- Haytian Papers

- Matt Clavin, "Race, Rebellion, and the Gothic Inventing the Haitian Revolution," Early American Studies: And Interdisciplinary Journal 5, no. 1 (2007), 12.

- Prince Saunders, Haytian Papers (London, England: W. Reed, 1816).

- Willie Harrell, "A Call to Consciousness and Action: Mapping the African American Jeremiad." Canadian Review of American Studies 36, no. 2 (2006), 164.

- Alice Moore Dunbar, ed., Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2000).

- Alice Moore Dunbar, ed., Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2000), 18.

- Leslie Charles, Autobiographical Recollections (London, England: John Murray, 1860), 162

External links

Bibliography

- "African-Americans Explore Haiti", Haiti & the USA

- "Prince Saunders: An Instance of Social Mobility Among Antebellum New England Blacks", The Journal of Negro History

- "The Colored American",

- "RE: Prince Sanders (Saunders)", Webster University Haiti mailing list

- Bardolph, Richard. "Social Origins of Distinguished Negros, 1770-1865: Part I." The Journal of Negro History 40, no. 3 (1955): 211-249

- Clavin, Matt. "Race, Rebellion, and the Gothic Inventing the Haitian Revolution." Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 5, no. 1 (2007): 1-29.

- Henri Christophe, King of Haiti, 1767-1820. Henry Christophe & Thomas Clarkson: a Correspondence. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952.

- Ernst, Robert. "Negro Concepts of Americanism." The Journal of Negro History 39, no. 3 (1954): 206-219.

- Fordham, Monroe. "Nineteenth-Century Black Thought in the United States: Some Influences of the Santo Domingo Revolution." Journal of Black Studies 6, no. 2 (1975): 115-126.

- Harrell, Willie. "A Call to Consciousness and Action: Mapping the African-American Jeremiad." Canadian Review of American Studies 36, no. 2 (2006): 149-180

- Leslie, Charles. Autobiographical Recollections. London, England: John Murray, 1860

- Miller, Chrislaine Pamphile. Blessed are the Peacemakers: African American Emigration to Haiti: 1816-1826. University of California-- Santa Cruz, 2013.

- Newman, Richard, and Patrick Rael, and Phillip Lapsansky. Pamphlets of Protest: an anthology of early African-American protest literature, 1790-1860. London, England: Routledge, 2000.

- Saunders, Prince. Haytian Papers. London, England: Law Booksellers, 1816.

- Voorhis, Harold van Buren. Negro Masonry in the United States. Montana: Kessinger Publishing, 1995.

- White, Arthur. "Prince Saunders: An Instance of Social Mobility Among Antebellum New England Blacks." The Journal of Negro History 60, no. 4 (October 1975): 526-535.

- White, Arthur. "The Black Leadership Class and Education in Antebellum Boston." The Journal of Negro History 42, no. 4 (1975): 526-535