Echinognathus

Echinognathus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Classified as part of the family Megalograptidae, the genus contains one only species, E. clevelandi, whose fossils have been found in deposits from the Katian age of the Late Ordovician period of New York.[1] The name of the species, clevelandi, honors William N. Cleveland, who found the specimens that were used for the description of Echinognathus.[2]

| Echinognathus | |

|---|---|

| |

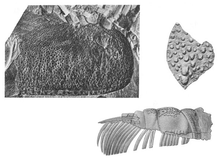

| Fossils of E. clevelandi. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Carcinosomatoidea |

| Family: | †Megalograptidae |

| Genus: | †Echinognathus Walcott, 1882 |

| Type species | |

| †Echinognathus clevelandi Walcott, 1882 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The genus is classified as part of the Megalograptidae family of eurypterids, a family differentiated from other eurypterids by the possession of two or more pairs of spines per podomere on prosomal appendage IV, a reduction of almost all spines and the large exoskeletons with ovate to triangular scales.[3][4] With the biggest specimen measuring 45 centimetres (18 inches) in length, Echinognathus is the smallest member of Megalograptidae.[5]

Description

Echinogntahus was a medium-sized eurypterid at an estimated length of 45 cm. This size makes it the smallest megalograptid to date, being surpassed by Pentecopterus decorahensis with a length of 1.83 m (6 feet) or Megalograptus shideleri at 2 m (6.2 ft) (although this is based on two incomplete and fragmented tergites that make this size doubtful).[5]

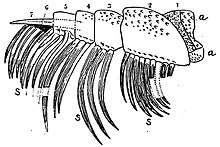

The type species of Echinognathus is a cephalic appendage with endognathary limbs found in the Utica Shale. This appendage is composed of 8 or 9 joints of which 6 has long, curved spines. The terminal joint is slender, elongate and acuminate. The larger joints of the cephalic appendage are ornamented with scale-like markings, a characteristic that has also been present in Pterygotus. The long curved spines are one of the main characteristics of the genus. The function of these spines is unknown, and it has been suggested that they have some relationship with the branchial system of the animal, since there is no evidence that they had served to bring food to the mouth.[2]

Classification

Echinognathus is classified within the family Megalograptidae in the monotypic superfamily Megalograptoidea.[1] Echinognathus is distinguishable from other members of the family by the third walking legs, which are characterized by long, closely set spines.[4]

The cladogram below is simplified from a study by Lamsdell et al. (2015),[3] showing the phylogenetic positions of the genera within Megalograptidae.

| Megalograptidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2015. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch, version 16.0 http://www.wsc.nmbe.ch/resources/fossils/Fossils16.0.pdf (PDF).

- Walcott, C.D. (1882). "Description of a New Genus of the Order Eurypterida from the Utica Slate". The American Journal of Science. 23 (135): 213–216.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (September 1, 2015). "The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15: 169. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. PMC 4556007. PMID 26324341.

- Størmer, Leif (1955). "Merostomata". Part P Arthropoda 2, Chelicerata. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. p. 36.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2009-10-14). "Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates". Biology Letters: rsbl20090700. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. ISSN 1744-9561. PMID 19828493. Supplementary information Archived 2018-02-28 at the Wayback Machine