Durrës

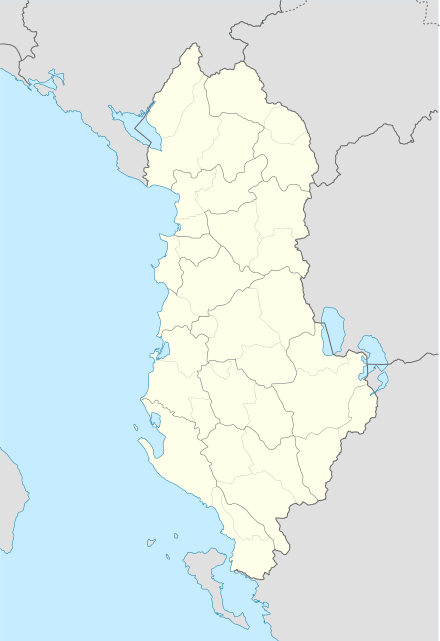

Durrës (UK: /dʊˈrəs/ DU-res,[1] US: /dʊrˈəs/ DOOR-us,[2] Albanian: [ˈdu:rəs] or [ˈdu:rəsi]) is the second most populous city of the Republic of Albania and the capital of the eponymous county and municipality. Situated on a flat plain on the southeastern shore of the Adriatic Sea, its climate is profoundly influenced by a Mediterranean seasonal climate.

Durrës | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Panorama of Durrës, Mosaics at a Basilica within the Amphitheatre, Venetian Tower of Durrës, the Albanian College, Church of Apostle Paul, Ancient Walls of Durrës, Amphitheatre of Durrës and Iliria Square. | |

Emblem | |

Durrës | |

| Coordinates: 41°19′N 19°27′E | |

| Country | |

| County | Durrës |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Valbona Sako (PS) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 338.96 km2 (130.87 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Municipality | 175,110 |

| • Municipality density | 520/km2 (1,300/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 113,249 |

| Demonym(s) | Durrsak, Durrsake |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal Code | 2001–2009 |

| Area Code | (0)52 |

| Website | durres.gov.al |

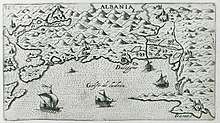

Durrës was founded by ancient Greek colonists from Corinth and Corfu under the name of Epidamnos around the 7th century BC on the coast of the Illyrian Taulantii.[3] Later known as Dyrrachium, it essentially developed to become significant as it became an integral part of the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. The Via Egnatia, the continuation of the Via Appia, started in the city and led across the interior of the Balkan Peninsula to Constantinople in the east.

In the Middle Ages, it was contested between Bulgarian, Venetian and Ottoman dominions. Following the Albanian Declaration of Independence, the city served as the capital of the Principality of Albania for a short period of time. Subsequently, it was annexed by the Kingdom of Italy and Nazi Germany in the interwar period. The city experienced a strong expansion in its demography and economic activity during Communism in Albania.

Durrës is served by the Port of Durrës, one of the largest on the Adriatic Sea, which connects the city to Italy and other neighbouring countries. Its most considerable attraction is the Amphitheatre of Durrës that is included on the tentative list of Albania for designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Once having a capacity for 20,000 people, it is the largest amphitheatre in the Balkan Peninsula.

Name

In antiquity, the city was named Epidamnos (Ἐπίδαμνος) and Dyrrhachion (Δυρράχιον) in classical Greek and then Epidamnus and Dyrrachium in classical Latin. Epidamnos is the older of the two toponyms. It is attested in Thycidides (5th century BC), Aristotle (4th century BC) and Polybius (2nd century BC). Dyrrachium became the name of the city after the Roman Republic got control of the region after the Illyrian Wars in 229 BC.[4] The Latin spelling of /y/ retained the form of Doric Greek Dyrrhachion, which was pronounced as /Durrakhion/. This change of the name is already attested in classical literature. Titus Livius, at the end of the first century BC, writes in Ab Urbe Condita Libri that at the time of the Illyrian Wars (roughly 200 years earlier) the city was not known as Dyrrachium, but as Epidamnus. Pomponius Mela, about 70 years later than Titus Livius, attributed the change of the name to the fact that the name Epidamnos reminded to the Romans the Latin word damnum, which to them signified evil and bad luck. Pliny the Elder, who lived in the same period, repeated this explanation in his own works. The Romans also adopted the new name because it was already in more frequent use by the citizens of the city.[5]

The name Dyrrhachion is usually explained as a Greek compound from δυσ- 'bad' and ῥαχία 'rocky shore, flood, roaring waves',[6] an explanation already hinted at in antiquity by Cassius Dio, who writes it referred to the difficulties of the rocky coastline,[7] while also reporting that other Roman authors linked it to the name of an eponymous hero Dyrrachius. The mythological construction of the city's name was recorded by Appian (2nd century AD) who wrote that the king of the barbarians of this country, Epidamnus gave the name to the city. His daughter's son Dyrrachius, built a port near the town that he called Dyrrachium. Stephanus of Byzantium repeated this mythological construction in his work. It is unclear whether the two toponyms referred originally to different areas of the territory of the city or whether they referred to the same territory.[8] Classical literature indicates that they more probably referred to different neighbouring areas originally. Gradually, the name Epidamnus fell out of use and Dyrrachium became the sole name for the city.[9]

The modern names of the city in Albanian (Durrës) and Italian (Durazzo, Italian pronunciation: [duˈrattso]) are derived from Dyrrachium/Dyrrachion. An intermediate, palatalized antecedent is found in the form Dyrratio, attested in the early centuries AD. The palatalized /-tio/ ending probably represents a phonetic change in the way the inhabitants of the city pronounced its name.[10] The preservation of old Doric /u/ indicates that the modern name derives from populations to whom the toponym was known in its original Doric pronunciation.[11] By contrast, in Byzantine Greek, the name of the city is pronounced with the much later evolution of /u/ as /i/. The modern Italian name evolved in the sub-dialects that emerged from Colloquial Latin in northern Italy.[12] The modern Albanian name evolved independently from the parent language of Albanian around the same period of the post-Roman era in the first centuries AD as the difference in stress in the two toponyms (first syllable in Albanian, second in Italian) highlights.[10]

In English usage, the Italian form Durazzo used to be widespread, but the local Albanian name Durrës has gradually replaced it in recent decades.

History

Antiquity

Though surviving remains are minimal,[13] Durrës is one of the oldest cities in Albania. In terms of mythology the foundation of the settlement is connected with the legendary hero Herakles who supported the local ruler, Dyrrachus, in the struggle against his brothers. As such in historical times the locals claimed Heracles as one of their founders.[14]

Several ancient people held the site: the presence of the Brygi appears to be confirmed by several ancient writers, the Illyrian Taulantii (their arrival has been estimated to have happened not later than the 10th century BC), probably the Liburni who expanded southwards in the 9th century BC.[15][16][17] The city was founded by Greek colonists in 627 BC on the coast of the Taulantii.[3] According to ancient authors, the Greek colonists helped the Taulantii to expel Liburnians and mixed with the local population establishing the Greek element to the port.[16]

Under Agron, the Illyrian Ardiaei captured and later fortified Epidamnus (c. 250-231 BC).[18] When the Romans defeated the Illyrians, they replaced the rule of queen Teuta with that of Demetrius of Pharos, one of her generals.[19] He lost his kingdom, including Epidamnus, to the Romans in 219 BC at the Second Illyrian War. In the Third Illyrian War Epidamnus was attacked by Gentius but he was defeated by the Romans[20] at the same year.

For Catullus, the city was Durrachium Hadriae tabernam, "the taberna of the Adriatic", one of the stopping places for a Roman traveling up the Adriatic, as Catullus had done himself in the sailing season of 56.[21]

After the Illyrian Wars with the Roman Republic in 229 BC ended in a decisive defeat for the Illyrians, the city passed to Roman rule, under which it was developed as a major military and naval base. The Romans renamed it Dyrrachium (Greek: Δυρράχιον / Dyrrhachion). They considered the name Epidamnos to be inauspicious because of its wholly coincidental similarities with the Latin word damnum, meaning "loss" or "harm". The meaning of Dyrrachium ("bad spine" or "difficult ridge" in Greek) is unclear, but it has been suggested that it refers to the imposing cliffs near the city. Julius Caesar's rival Pompey made a stand there in 48 BC before fleeing south to Greece. Under Roman rule, Dyrrachium prospered; it became the western end of the Via Egnatia, the great Roman road that led to Thessalonica and on to Constantinople. Another lesser road led south to the city of Buthrotum, the modern Butrint. The Roman emperor Caesar Augustus made the city a colony for veterans of his legions following the Battle of Actium, proclaiming it a civitas libera (free town).

In the 4th century, Dyrrachium was made the capital of the Roman province of Epirus nova. It was the birthplace of the emperor Anastasius I in c. 430. Sometime later that century, Dyrrachium was struck by a powerful earthquake which destroyed the city's defences. Anastasius I rebuilt and strengthened the city walls, thus creating the strongest fortifications in the western Balkans. The 12-metre-high (39-foot) walls were so thick that, according to the Byzantine historian Anna Komnene, four horsemen could ride abreast on them. Significant portions of the ancient city defences still remain, although they have been much reduced over the centuries.

Like much of the rest of the Balkans, Dyrrachium and the surrounding Dyrraciensis provinciae suffered considerably from barbarian incursions during the Migrations Period. It was besieged in 481 by Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths, and in subsequent centuries had to fend off frequent attacks by the Bulgarians. Unaffected by the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the city continued under the Byzantine Empire as an important port and a major link between the Empire and western Europe.

Middle Ages

The city and the surrounding coast became a Byzantine province, the Theme of Dyrrhachium, probably in the first decade of the 9th century.[22] The city remained in Byzantine hands until the late 10th century, when Samuel of Bulgaria gained control of the city, possibly through his marriage with Agatha, daughter of the local magnate John Chryselios. Samuel made his son-in-law Ashot Taronites, a Byzantine captive who had married his daughter Miroslava, governor of the city. In circa 1005, however, Ashot and Miroslava, with the connivance of Chryselios, fled to Constantinople, where they notified Emperor Basil II of their intention to surrender the city to him. Soon, a Byzantine squadron appeared off the city under Eustathios Daphnomeles, and the city returned to Byzantine rule.[23][24]

In the 11th–12th centuries, the city was important as a military stronghold and a metropolitan see rather than as a major economic center, and never recovered its late antique prosperity; Anna Komnene makes clear that medieval Dyrrhachium occupied only a portion of the ancient city.[22] In the 1070s, two of its governors, Nikephoros Bryennios the Elder and Nikephoros Basilakes, led unsuccessful rebellions trying to seize the Byzantine throne.[22] Dyrrachium was lost in February 1082 when Alexios I Komnenos was defeated by the Normans under Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund in the Battle of Dyrrhachium. Byzantine control was restored a few years later, but the Normans under Bohemund returned to besiege it in 1107–08, and sacked it again in 1185 under King William II of Sicily.[22]

In 1205, after the Fourth Crusade, the city was transferred to the rule of the Republic of Venice, which formed the "Duchy of Durazzo". This Duchy was conquered in 1213 and the city taken by the Despotate of Epirus under Michael I Komnenos Doukas. In 1257, Durrës was briefly occupied by the King of Sicily, Manfred of Hohenstaufen. It was re-occupied by the Despot of Epirus Michael II Komnenos Doukas until 1259, when the Despotate was defeated by the Byzantine Empire of Nicaea in the Battle of Pelagonia. In the 1270s, Durrës was again controlled by Epirus under Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas, the son of Michael II, who in 1278 was forced to yield the city to Charles d' Anjou (Charles I of Sicily). In c. 1273, it was wrecked by a devastating earthquake (according to George Pachymeres[25]) but soon recovered. It was briefly occupied by King Milutin of Serbia in 1296. In the thirteenth century, a Jewish community existed in Durrës and was employed in the salt trade.[26]

In the early 14th century, the city was ruled by a coalition of Anjous, Hungarians, and Albanians of the Thopia family. In 1317 or 1318, the area was taken by the Serbs and remained under their rule until the 1350s. At that time the Popes, supported by the Anjous, increased their diplomatic and political activity in the area, by using the Latin bishops, including the archbishop of Durrës. The city had been a religious center of Catholicism after the Anjou were installed in Durrës. In 1272, a Catholic archbishop was installed, and until the mid-14th century there were both Catholic and Orthodox archbishops of Durrës.[27]

Two Irish pilgrims who visited Albania on their way to Jerusalem in 1322, reported that Durrës was "inhabited by Latins, Greeks, perfidious Jews and barbaric Albanians".[28]

When the Serbian Tsar Dušan died in 1355, the city passed into the hands of the Albanian family of Thopias. In 1376 the Navarrese Company Louis of Évreux, Duke of Durazzo, who had gained the rights on the Kingdom of Albania from his second wife, attacked and conquered the city, but in 1383 Karl Topia regained control of the city.[29] The Republic of Venice regained control in 1392 and retained the city, known as Durazzo in those years, as part of the Albania Veneta. It fended off a siege by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II in 1466 but fell to Ottoman forces in 1501.

Durrës became a Christian city quite early on; its bishopric was created around 58 and was raised to the status of an archbishopric in 449. It was also the seat of an Orthodox metropolitan bishop. Under Ottoman rule, many of its inhabitants converted to Islam and many mosques were erected. The city was renamed Dıraç but did not prosper under the Ottomans and its importance declined greatly. Following the establishment of Ottoman rule in 1501, the Durrës Jewish community experienced population growth.[26]

By the mid-19th century, its population was said to have been only about 1,000 people living in some 200 households. In the late nineteenth century, Durrës contained 1,200 Orthodox Aromanians (130 families) who lived among the larger population of Muslim Albanians alongside a significant number of Catholic Albanians.[30] The decrepitude of Durrës was noted by foreign observers in the early 20th century: "The walls are dilapidated; plane-trees grow on the gigantic ruins of its old Byzantine citadel; and its harbour, once equally commodious and safe, is gradually becoming silted up."[31] Durrës was a main centre in İşkodra Vilayet before 1912.

Modern

Durrës was an active city in the Albanian national liberation movement in the periods 1878–1881 and 1910–1912. Ismail Qemali raised the Albanian flag on 26 November 1912 but the city was occupied by the Kingdom of Serbia three days later during the First Balkan War. On 29 November 1912 Durrës became the county town of the Durrës County (Serbian: Драчки округ) one of the counties of the Kingdom of Serbia established on the part of the territory of Albania occupied from Ottoman Empire. The Durrës County had four districts (Serbian: срез): Durrës, Lezha, Elbasan and Tirana.[32] The army of the Kingdom of Serbia retreated from Durrës in April 1913.[33] The city became Albania's second national capital (after Vlora) on 7 March 1914 under the brief rule of Prince William of Wied.[34] It remained Albania's capital until 11 February 1920, when the Congress of Lushnjë made Tirana the new capital.

During the First World War, the city was occupied by Italy in 1915 and by Austria-Hungary in 1916–1918. On 29 December 1915, a Naval Battle was fought off Durazzo. On 2 October 1918, several allied ships bombarded Durazzo and attacked the few Austrian ships in the harbour. Although civilians started to flee the city at the start of the bombardment, many casualties were inflicted on the innocent and neutral population. The Old City being adjacent to the harbour was largely destroyed, including the Royal Palace of Durrës and other primary public buildings. It was captured by Italian troops on 16 October 1918. Restored to Albanian sovereignty, Durrës became the country's temporary capital between 1918 and March 1920. It experienced an economic boom due to Italian investments and developed into a major seaport under the rule of King Zog, with a modern harbour being constructed in 1927. It was at this time the Royal Villa of Durrës was built by Zog as a summer palace, that still dominates the skyline from a hill close to the old city.

An earthquake in 1926 damaged some of the city and the rebuilding that followed gave the city its more modern appearance. During the 1930s, the Bank of Athens had a branch in the city.

Durrës (called Durazzo again in Italian) and the rest of Albania were occupied in April 1939 and annexed to the Kingdom of Italy until 1943, then occupied by Nazi Germany until autumn 1944. Durrës's strategic value as a seaport made it a high-profile military target for both sides. It was the site of the initial Italian landings on 7 April 1939 (and was fiercely defended by Mujo Ulqinaku) as well as the launch point for the ill-fated Italian invasion of Greece. The city was heavily damaged by Allied bombing during the war and the port installations were blown up by retreating German soldiers in autumn 1944.

The Communist regime of Enver Hoxha rapidly rebuilt the city following the war, establishing a variety of heavy industries in the area and expanding the port. It became the terminus of Albania's first railway, begun in 1947 (Durrës–Tiranë railway). In the late 1980s, the city was briefly renamed Durrës-Enver Hoxha. The city was and continues to remain the center of Albanian mass beach tourism.

Following the collapse of communist rule in 1990, Durrës became the focus of mass emigrations from Albania with ships being hijacked in the harbour and sailed at gunpoint to Italy. In one month alone, August 1991, over 20,000 people migrated to Italy in this fashion. Italy intervened militarily, putting the port area under its control, and the city became the center of the European Community's "Operation Pelican", a food-aid program.

In 1997, Albania slid into anarchy following the collapse of a massive pyramid scheme which devastated the national economy. An Italian-led peacekeeping force was controversially deployed to Durrës and other Albanian cities to restore order, although there were widespread suggestions that the real purpose of "Operation Alba" was to prevent economic refugees continuing to use Albania's ports as a route to migrate to Italy.

Following the start of the 21st century, Durrës has been revitalized as many streets were repaved, while parks and façades experienced a face lift.

Geography

Durrës is located in a flat alluvial plain on the southeastern Adriatic Sea at one of the narrower points opposite the cities of Bari and Brindisi in Italy.[35] It lies mostly between latitudes 41° and 19° N and longitudes 19° and 27° E. By air distance, it is 165 kilometres (103 miles) northwest of Sarandë, 31 kilometres (19 miles) west of Tirana, 83 kilometres (52 miles) south Shkodër and 579 kilometres (360 miles) east of Rome.

Climate

The climate of the city is profoundly impacted by the Mediterranean Sea in the west. Furthermore, it experiences a Mediterranean climate with continental influences. The summers are predominantly hot and dry, the winters relatively mild, and falls and springs mainly stable, in terms of precipitation and temperatures.[35]

| Climate data for Durrës | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

20.1 (68.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.9 (75.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 132 (5.2) |

107 (4.2) |

99 (3.9) |

81 (3.2) |

68 (2.7) |

41 (1.6) |

26 (1.0) |

36 (1.4) |

71 (2.8) |

112 (4.4) |

160 (6.3) |

131 (5.2) |

1,064 (41.9) |

| Source: [36] | |||||||||||||

Demography

Population

| Population growth of Durrës in selected periods | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1923[37] | 1927[37] | 1938[37] | 1979 | 1989 | 2001[38] | 2011[38] |

| Pop. | 4,785 | 5,175 | 10,506 | 66,200 | 82,719 | 99,546 | 113,249 |

| ±% p.a. | — | +1.98% | +6.65% | +4.59% | +2.25% | +1.56% | +1.30% |

| Source: [37][38] | |||||||

Durrës is the second most populous municipality in Albania and one of the most populous on the Adriatic Sea with a growing number of inhabitants. According to the 2011 census, the municipal unit of Durrës had an estimated population of 113,249 of whom 56,511 were men and 56,738 women.[39]

Following the territorial and administrative reform of 2015, the municipality of Durrës consists of the five adjacent municipalities of Ishëm, Katund i Ri, Manëz, Rrashbull and Sukth.[40] Their combined population stands at 175,110, as of 2011.[38]

Religion

Albania is a secular state with no state religion and the freedom of belief, conscience and religion is explicitly guaranteed in the constitution of the country.[41][42] Durrës is therefore religiously diverse and has many places of worship catering to its religious population, whom are adherents of Christianity, Islam and Judaism.

Christianity in Albania has a presence dating back to classical antiquity. Christian traditions relate that the archbishopric of Durrës was founded by the apostle Paul while preaching in Illyria and Epirus and that there were possibly about seventy Christian families in Durrës as early as the time of the Apostles.[43][44] The Orthodox Church of Albania, which has been autocephalous since 1923 was divided into the archbishopric of Tirana – Durrës, headed by the Metropolitan and sub-divided into the local church districts of Tirana, Durrës, Shkodër and Elbasan.[43] The religious composition of Durrës consists of Muslims, both (Sunni and Bektashi) alongside Christians (Catholic and Orthodox) who form a significant part of the urban population.

Governance

Durrës is the capital of the eponymous county and municipality.[40] Durrës is traditionally governed by the mayor of Durrës and the city council.[45] The city council is made up of 51 councilors directly elected every four years by the city's population.[45]

Economy

Durrës is an important link to Western Europe due to its port and its proximity to the Italian port cities, notably Bari, to which daily ferries run. As well as the dockyard, it also possesses an important shipyard and manufacturing industries, notably producing leather, plastic and tobacco products.

The southern coastal stretch of Golem is renowned for its traditional mass beach tourism having experienced uncontrolled urban development. The city's beaches are also a popular destination for many foreign and local tourists, with an estimated 800,000 tourists visiting annually. Many Albanians from Tirana and elsewhere spend their summer vacations on the beaches of Durrës. In 2012, new water sanitation systems are being installed to completely eliminate sea water pollution. In contrast, the northern coastal stretch of Lalzit Bay is mostly unspoiled and set to become an elite tourism destination as a number of beach resorts are being built since 2009. Neighboring districts are known for the production of good wine and a variety of foodstuffs.

According to the World Bank, Durrës has made significant steps of starting a business in 2016. Durrës ranks ninth[53] among 22 cities in Southeastern Europe before the capital Tirana, Belgrade, Serbia and Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Infrastructure

Transportation

.jpg)

Major roads and railways pass through the city of Durrës thank to its significant location and connect the northern part of the country to the south and the west with the east. Durrës is the starting point of Pan-European Corridor VIII, national roads SH2 and SH4, and serves as the main railway station of the Albanian Railways (HSH).

The Pan-European Corridor VIII is one of the Pan-European corridors. It runs between Durrës, at the Adriatic coast, and Varna, at the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. The National Road 2 (SH2) begins at the Port of Durrës at the Dajlani Overpass, bypasses the road to Tirana International Airport, and ends at the Kamza Overpass in the outskirts of Tirana where it meets National Road 1 (SH1) State Road heading to northern Albania. The Albania–Kosovo Highway is a four-lane highway constructed from 2006 to 2013 between Albania and Kosovo. As part of the South-East European Route 7,[54] the highway will connect the Adriatic Sea ports of Durrës via Pristina, with the E75/Corridor X near Niš, Serbia. As most tourists come through Kosovo, the laying of the highway make it easier to travel to Durrës.

The very advantageous geographical location makes the port of Durrës to the greatest port of Albania, and among the largest in the Adriatic and Ionian Sea. The port is located in the south-western part of Durrës it is an artificial basin that is formed between two moles, with a west-northwesterly oriented entrance approximately wide as it passes between the ends of the moles. Port of Durrës is also a key location for transit networks and passenger ferry, giving Durrës a strategic position with respect to the Pan-European Corridor VIII. The port has experienced major upgrades in recent years culminating with the opening of the new terminal in July 2012. In 2012, The Globe and Mail ranked Durrës at no. 1 among 8 exciting new cruise ports to explore.[55] It is one of the largest passenger port on the Adriatic Sea that handle more than 1.5 million passengers per year.

The rail station of Durrës is connected to other cities in Albania, including Vlorë and the capital of Tirana. The Durrës–Tiranë railway was a 38-kilometre (24-mile) railway line which joined the two biggest cities in Albania: Durrës and Tiranë. The line connects to the Shkodër–Vorë railway halfway in Vorë, and to the Durrës-Vlorë railway in Durrës. In 2015, some rail stations and rolling stock along the Durrës-Tiranë line are being upgraded and latter colored red and white.

In October 2016 they will start building a new railway with the cost of €81.5 million. And it is expected that it will be used around 1.4 million times a year.[56]

Education

Durrës has a long tradition of education since the beginning of civil life from antiquity until today. After the fall of communism in Albania, a reorganization plan was announced in 1990, that would extend the compulsory education program from eight to ten years. The following year, major economic and political crisis in Albania, and the ensuing breakdown of public order, plunged the school system into chaos. Later, many schools were rebuilt or reconstructed, to improve learning conditions especially in larger cities of the country. Durrës is host to academic institutions such as the University of Durrës, Albanian College of Durrës, Kajtazi Brothers Educational Institute, Gjergj Kastrioti High School, Naim Frashëri High School, Sports mastery school Benardina Qerraxhiu and Jani Kukuzeli Artistic Lycee.

Culture

One of the city's main sights is the Byzantine city wall, also called Durrës Castle, while the largest amphitheatre in the Balkans is found close to the city's harbour. This fifth-century construction is currently under consideration for inscription as a UNESCO World Heritage site.[57]

The theatrical and musical life of the city is constituted by the Aleksandër Moisiu Theatre, the Estrada Theater, a puppet theater, and the philharmonic orchestra. The International Film Summerfest of Durrës, founded in 2008, has since takes place every year in late August or early September in Durrës Amphitheatre. In 2004 and 2009 Miss Globe International was held in Durrës.

The city is home to different architectural styles that represent influential periods in its history. The architecture is influenced by Illyrian, Greek, Roman and Italian architecture. In the 21st century, part of Durrës has turned into a modernist city, with large blocks of flats, modern new buildings, new shopping centres and many green spaces.

Museums

Durrës is home to the largest archaeological museum in the country, the Durrës Archaeological Museum, located near the beach. North of the museum are the sixth-century Byzantine walls constructed after the Visigoth invasion of 481. The bulk of the museum consists of artifacts found in the nearby ancient site of Dyrrhachium and includes an extensive collection from the Illyrian, Ancient Greek, Hellenistic and Roman periods. Items of major note include Roman funeral steles and stone sarcophagi, an elliptical colourful mosaic measuring 17 by 10 feet, referred to as The Beauty of Durrës, and a collection of miniature busts of Venus, testament to the time when Durrës was a centre of worship of the goddess. There are several further museums such as the Royal Villa of Durrës and the Museum of History (the house of Aleksandër Moisiu).

See also

Further reading

References

- "Durrës". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Durrës". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- George Grote (2013). A History of Greece: From the Time of Solon to 403 BC. Routledge. p. 440.

- Demiraj 2006, p. 126.

- Demiraj 2006, p. 127.

- Krahe, Hans (1964). "Vom Illyrischen zum Alteuropäischen". Indogermanische Forschungen. 69: 202.

- Cassius Dio (1916). "41:49". Roman History. IV. Loeb Classical Library. p. 85.

- Demiraj 2006, p. 128.

- Demiraj 2006, p. 129.

- Demiraj 2006, pp. 133–34

- Demiraj 2006, p. 132.

- Bonnet, Guillaume (1998). Les mots latins de l'albanais. Paris: L'Harmattan. p. 37.

- A selection of modern travelers' accounts and references in ancient literature are given in P. Cabanes and F. Drini, eds, Inscription d'Épidamne-Dyrrhachion et d'Apollonia, vol. I (1995)

- Wilkes, John (1996). The Illyrians. Wiley. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-631-19807-9.

- Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (1970). The Cambridge Ancient History:The Prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. III. Cambridge University Press. p. 628. ISBN 0-521-22496-9.

- Wilkes 1995, p. 111: In a later period the Bryges, returning from Phrygia, seized the city and surrounding territory, then the Taulantii, an Illyrian people, took it from them and the Liburni, another Illyrian people, took it from the Taulantii [...] Those expelled from Dyrrhachium by the Liburnians obtained help from the Corcyreans then masters of the sea and drove out the Liburni.

- Cabanes, Pierre (2008), "Greek Colonisation in the Adriatic", in Tsetskhladze, G.R. (ed.), reek Colonisation: An Account of Greek Colonies and Other Settlements Overseas, II, BRILL, p. 163, ISBN 9789047442448CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkes 1995, p. 158

- Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians, 1992, p. 120, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, page 161, "... Gulf of Kotor. The Romans decided that enough had been achieved and hostilities ceased. The consuls handed over Illyria to Demetrius and withdrew the fleet and army to Epidamnus, ..."

- John Drogo Montagu, Battles of the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Chronological Compendium of 667 Battles to 31BC, (series Historians of the Ancient World (Greenhill Historic Series), 2000:47 ISBN 1-85367-389-7.

- M. Gwyn Morgan, "Catullus and the 'Annales Volusi'" Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica, New Series, 4 (1980):59–67).

- ODB, "Dyrrachion" (T. E. Gregory), p. 668.

- Stephenson 2003, pp. 17–18, 34–35.

- Holmes 2005, pp. 103–104, 497–498.

- R. Elsie, Early Albania (2003), p. 12

- Giakoumis, Konstantinos (2010). "The Orthodox Church in Albania Under the Ottoman Rule 15th-19th Century". In Schmitt, Oliver Jens (ed.). Religion und Kultur im albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa [Religion and culture in Albanian-speaking southeastern Europe]. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9783631602959.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Etleva Lala (2008) Regnum Albaniae, the Papal Curia, and the Western Visions of a Borderline Nobility" (PDF).

- Itinerarium Symonis Simeonis et Hugonis Illuminatoris ad Terram Sanctam, edited by J. Nasmith, 1778, cited in:

Elsie Robert, The earliest references to the existence of the Albanian language. Zeitschrift für Balkanologie, Munich, 1991, v. 27.2, pp. 101–105.

Available at https://www.scribd.com/doc/87039/Earlies-Reference-to-the-Existance-of-the-Albanian-Language Archived 2011-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Inhabitatur enim Latinis, Grecis, Judeis perfidis, et barbaris Albanensibus" (Translation in R. Elsie: For it is inhabited by Latins, Greeks, perfidious Jews and barbaric Albanians).

- Fine (1994), p. 384

- Koukoudis, Asterios (2003). The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora. Thessaloniki: Zitros Publications. p. 358. ISBN 9789607760869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "Durrës... At the end of the nineteenth century, there were more than 130 Vlach families, some 1,200 Vlachs, who constituted the nucleus of the local Greek Orthodox community, amid the much more numerous Moslem Albanians and quite a number of Roman Catholics, also of Albanian stock."

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 695.

- Bogdanović, Dimitrije; Radovan Samardžić (1990). Knjiga o Kosovu: razgovori o Kosovu. Književne novine. p. 208. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

На освојеном подручју су одмах успостављене грађанске власти и албанска територија је Де Факто анектирана Србији : 29. новембра је основан драчки округ са четири среза (Драч, Љеш, Елбасан, Тирана)....On conquered territory of Albania was established civil government and territory of Albania was de facto annexed by Serbia: On November 29 was established Durrës County with four srez (Durrës, Lezha, Elbasan and Tirana)

- Antić, Čedomir (January 2, 2010). "Kratko slavlje u Draču" [Short celebration in Durrës]. Večernje novosti (in Serbian). Retrieved 5 August 2011.

VeĆ u aprilu 1913. postalo je izvesno da je kraj "albanske operacije" blizu. Pod pritiskom flote velikih sila srpska vojska je napustila jadransko primorje. ...In April 1913 it became obvious that the "Albanian operation" is over. Under pressure of the fleet of Great Powers army of Serbia retreated from the Adriatic coast.

- Organic Statute of the Principality of Albania (in Albanian) Archived 2012-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, http://licodu.cois.it

- "PROGRAMI I ZONES FUNKSIONALE - BASHKIA E RE DURRES -" (PDF). km.dldp.al (in Albanian). Durrës. pp. 7–9.

- "Climate: Durrës". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Hemming, Andreas; Pandelejmoni, Enriketa; Kera, Gentiana. Albania: Family, Society and Culture in the 20th Century. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 37. ISBN 9783643501448.

- "ALBANIEN: Gliederung; Gemeinden und Gemeindeteile". citypopulation.de (in German). Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Ines Nurja. "Censusi i popullsisë dhe banesave / Population and Housing Census – Durrës 2011" (PDF) (in Albanian). Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). pp. 84–85. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Ligji Nr. 115/2014: Për ndarjen administrative-territoriale të njësive të Qeverisjes vendore në Republikën e Shqipërisë" (PDF) (in Albanian). p. 4. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Constitution of the Republic of Albania". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). p. 2.

- "Albania 2016 International Religious Freedom Report" (PDF). United States Department of State. pp. 1–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2017.

- http://biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/rcl/10-3_242.pdf

- "Early Christianity – Albania – Reformation Christian Ministries – Albania & Kosovo". reformation.edu.

- "Rreth Keshillit Bashkiak" (in Albanian). Bashkia Durrës. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- New consulate in Durrës improves Albania-Macedonia ties, SETimes.com, 13-08-13

- "Sister Cities of Istanbul". Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- Erdem, Selim Efe (1 July 2009). "İstanbul'a 49 kardeş" (in Turkish). Radikal. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

49 sister cities in 2003

- "Gemellaggio tra Bitonto e Durazzo, oggi il primo step Le foto". BitontoLive.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "Comune di Bari - Comune, del comune di Bari e città, Puglia". www.comune-italia.it. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "Kryebashkiaku i Durrësit Vangjush Dako nënshkruan marrëveshje bashkëpunimi me kryetarin e komunës së Ulqinit Gëzim Hajdinaga". www.durres.gov.al. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "Durrësi binjakëzohet me Selanikun - Arkiva Shqiptare e Lajmeve". www.arkivalajmeve.com. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "Subnational Economy Rankings – South East Europe – Subnational Doing Business – World Bank Group". doingbusiness.org.

- http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/projects-in-focus/donor-coordination/2-3_april_2009/working_group_transport_seeto_en.pdf

- 8 exciting new cruise ports to explore, The Globe and Mail, 2012-02-24

- "Bid Tender on Tirana-Durres-Rinas Railroad to Be Launched in October". 13 September 2016.

- "L'amphithéâtre de Durres". unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Centre.