Dunster

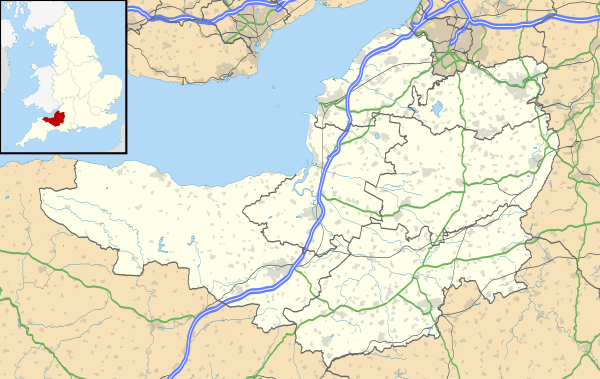

Dunster is a village, civil parish and former manor within the English county of Somerset, today just within the north-eastern boundary of the Exmoor National Park. It lies on the Bristol Channel coast 2.5 miles (4 km) south-southeast of Minehead and 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Taunton. The United Kingdom Census of 2011 recorded a parish population of 817.[1]

| Dunster | |

|---|---|

Dunster Yarn Market in the foreground and Dunster Castle on the skyline. | |

Dunster Location within Somerset | |

| Population | 817 [1] |

| OS grid reference | SS990436 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MINEHEAD |

| Postcode district | TA24 |

| Dialling code | 01643 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Devon and Somerset |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Website |

Iron Age hillforts testify to occupation of the area for thousands of years. The village grew up around Dunster Castle which was built on the Tor by the Norman warrior William I de Moyon (d. post 1090) shortly after the Norman Conquest of 1066. The Castle is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. From that time it was the caput of the Feudal barony of Dunster. The Castle was remodelled on several occasions by the Luttrell family who were lords of the manor from the 14th to 20th centuries. The benedictine Dunster Priory was established in about 1100. The Priory Church of St George, dovecote and tithe barn are all relics from the Priory.

The village became a centre for wool and cloth production and trade, of which the Yarn Market, built by George Luttrell (d.1629), is a relic. There existed formerly a harbour, known as Dunster Haven, at the mouth of the River Avill, yet today the coast having receded is now about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) from the village and no sign of the harbour can be seen on the low lying marshes between the village and the coast. Dunster has a range of heritage sites and cultural attractions which combine with the castle to make it a popular tourist destination with many visitors arriving on the West Somerset Railway, a heritage railway running from Minehad to Bishops Lydeard.

The village lies on the route of the Macmillan Way West, Somerset Way and Celtic Way Exmoor Option.

Name

The name Dunster derives from an earlier name Torre ("tor, rocky hill"), recorded in the Domesday Book written twenty years after the Norman conquest.[2] The origin of the prefix is uncertain, although it may well refer to Dunn, a Saxon noble who held land in nearby Elworthy and Willett before the conquest,[3] giving Dunestore meaning Dunn's craggy hill.[4]

The historian David Nash Ford proposed Dunster as a possible location of the Cair Draitou[5] listed by the History of the Britons as one of the 28 cities of Britain.[6]

History

Within 2 miles (3.2 km) of the village itself are several Iron Age hillforts showing evidence of early human occupation. These include Bat's Castle and Black Ball Camp on Gallox Hill,[7][8] Long Wood Enclosure[9][10][11] and a similar earthwork on Grabbist Hill.[12]

Dunster is mentioned as a manor and Dunster Castle as belonging to William I de Moyon (alias de Moion, also de Mohun) in the 1086 Domesday Book.[13] After the Norman conquest of England in the 11th century, he constructed a timber castle on the site as part of the pacification of Somerset.[14] A stone shell keep was built on the motte by the start of the 12th century, and the castle survived a siege during the early years of the Anarchy. At the end of the 14th century the de Mohuns sold the castle to the Luttrell family, who continued to occupy the property until the late 20th century.[15] During the English Civil War, Dunster was initially held as a garrison for the Royalists.[16] It fell to the Parliamentarians in 1645 and orders were sent out for the castle to be demolished.[16] However, these were not carried out, and the castle remained the garrison for Parliamentarian troops until 1650.[17] Dunster is regularly home to Taunton Garrison who re-enact plays, battles, and life in the civil war.[18] Major alterations to the castle were undertaken by Henry Fownes Luttrell who had acquired it through marriage to Margaret Fownes-Luttrell in 1747. Following the death of Alexander Luttrell in 1944, the family was unable to afford the death duties on his estate. The castle and surrounding lands were sold off to a property firm, the family continuing to live in the castle as tenants. The Luttrells bought back the castle in 1954, but in 1976 Colonel Walter Luttrell gave Dunster Castle and most of its contents to the National Trust, which operates it as a tourist attraction. It is a Grade I listed building and scheduled monument.

Dunster Priory was established as a Benedictine monastery around 1100. The first church in Dunster was built by William de Mohun who gave the church and the tithes of several manors and two fisheries, to the Benedictine Abbey at Bath. The priory, which was situated just north of the church, became a cell of the abbey.[19] The church was shared for worship by the monks and the parishioners, however this led to several conflicts between them. One outcome was the carved rood screen which divided the church in two with the parish using the west chancel and the monks the east.[20] The priory church is now in parochial use as the Priory Church of St George which still contains 12th and 13th century work, although most of the current building is from the 15th century. It has been designated as a Grade I listed building.[21][22] In 1332 it became more separated from the Abbey at Bath and became a priory in its own right.[23] In the "Valor Ecclesiasticus" of 1535 the net annual income of the Dunster Tithe Barn is recorded as being £37.4.8d (£37 23p), with £6.13s7d ( £6.68p ) being passed on to the priory in Bath.[24] In 1346 Cleeve Abbey built a nunnery in Dunster, but it was never inhabited by nuns and was used as a guest house.[25] The priory was dissolved as part of the dissolution of the monasteries in 1539. Dunster was part of the hundred of Carhampton,[26] but St George's was the seat of the local deanery, overseeing the area's parish churches.

The manors of Alcombe, Stanton (or Staunton), and Avill were also mentioned as settlements in the 1086 Domesday Book.[27][28]

Dunster had become a centre for woollen and clothing production by the 13th century, with the market dating back to at least 1222, and a particular kind of kersey or broadcloth became known as 'Dunsters'.[29][30] The prosperity of Dunster was based on the wool trade, with profits helping to pay for the construction of the tower of the Priory Church of St George and provide other amenities. The 15th century Gallox Bridge was one of the main routes over the River Avill on the southern outskirts.[31] The market was held in "The Shambles" however these shops were demolished in 1825 and now only the Yarn Market remains.[32]

Dunster Beach, which includes the mouth of the River Avill, is located half a mile from the village, and used to have a significant harbour, known as Dunster Haven, which was used for the export of wool from Saxon times;[30] however, it was last used in the 17th century and has now disappeared, as new land was laid down among the dykes, meadows and marshes near the shore.[33] During the Second World War, considerable defences were built along the coast as a part of British anti-invasion preparations, though the north coast of Somerset was an unlikely invasion site.[34] Some of the structures remain to this day. Most notable are the pillboxes on the foreshore of Dunster Beach.[35] These are strong buildings made from pebbles taken from the beach and bonded together with concrete. From these, soldiers could have held their ground if the Germans had ever invaded.[36] The beach site has a number of privately owned beach huts (or chalets as some owners call them) along with a small shop, a tennis court and a putting green. The chalets, measuring 18 by 14 feet (5.5 by 4.3 m), can be let out for holidays; some owners live in them all the year round.[37]

Governance

The parish council has responsibility for local issues, including setting an annual precept to cover the council’s operating costs and producing annual accounts for public scrutiny. The parish council evaluates local planning applications and works with the local police, district council officers, and neighbourhood watch groups on matters of crime, security, and traffic. The parish council's role also includes initiating projects for the maintenance and repair of parish facilities, as well as consulting with the district council on the maintenance, repair, and improvement of highways, drainage, footpaths, public transport, and street cleaning. Conservation matters (including trees and listed buildings) and environmental issues are also the responsibility of the council.

The village falls within the non-metropolitan district of Somerset West and Taunton, which was established on 1 April 2019. It was previously in the district of West Somerset, which was formed on 1 April 1974 under the Local Government Act 1972, and part of Williton Rural District before that.[38] The district council is responsible for local planning and building control, local roads, council housing, environmental health, markets and fairs, refuse collection and recycling, cemeteries and crematoria, leisure services, parks, and tourism. The larger and most expensive local services such as education, social services, libraries, main roads, public transport, policing and fire services, trading standards, waste disposal and strategic planning are the responsibility of Somerset County Council.

As Dunster falls within the Exmoor National Park, some functions normally administered by district or county councils have, since 1997, fallen under the Exmoor National Park Authority, which is known as a 'single-purpose' authority, whose purpose is to "conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage of the National Parks" and "promote opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of the Parks by the public",[39] including responsibility for the conservation of the historic environment.[40]

Dunster is the most populous area of the electoral ward named 'Dunster and Timbercombe'. The ward extends North East to the Bristol Channel and South West to Timberscombe. The total population at the 2011 Census was 1,219.[41]

It is also part of the Bridgwater and West Somerset county constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elects one Member of parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election, and is part of the South West England constituency of the European Parliament; the constituency elects seven MEPs using the d'Hondt method of party-list proportional representation.

Geography

Dunster Castle was positioned on a steep, 200-foot (61 m) high hill. Geologically, the hill is an outcrop of Hangman Grits, a type of red sandstone.[42] During the early medieval period the sea reached the base of the hill, close to the mouth of the River Avill, offering a natural defence and making the village an inland port.[43][44][45]

Nearby is the Dunster Park and Heathlands Site of Special Scientific Interest noted for nationally important lowland dry heath, dry lowland acid grassland, wood-pasture with veteran trees and ancient semi-natural oak woodland habitats. The fauna of the lowland heath includes the heath fritillary (Mellicta athalia), a nationally rare butterfly. The assemblage of beetles associated with the veteran trees is of national significance because of the variety and abundance of species.[46]

Along with the rest of South West England, Dunster has a temperate climate which is generally wetter and milder than the rest of England. The mean annual temperature in the area is 8.3 °C (46.9 °F) with a seasonal and diurnal variation, but due to the modifying effect of the sea the range is less than in most other parts of the UK. January is the coldest month, with mean minimum temperatures between 1 and 2 °C (34 and 36 °F). July and August are the warmest months in the region, with mean daily maxima around 21 °C (70 °F). In general, December is the month with the least sunshine and June the month with the most sun. The south west of England has a favoured location with regard to the Azores High when it extends its influence north-eastwards towards the UK, particularly in summer.[47] Cloud often forms inland, especially near hills, and reduce the amount of sunshine that reaches the park. The average annual sunshine is about 1,600 hours. Rainfall tends to be associated with Atlantic depressions or with convection. In summer, convection, caused by the sun heating the land surface more than the sea, sometimes forms rain clouds and at that time of year a large proportion of the rainfall comes from showers and thunderstorms. Annual precipitation is around 800 mm (31 in).[48] Local weather data is collected at Nettlecombe.[49]

| Climate data for Nettlecombe 96 m asl, 1971–2000 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

4.1 (39.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 123.6 (4.87) |

87.6 (3.45) |

80.6 (3.17) |

66.3 (2.61) |

62.6 (2.46) |

58.7 (2.31) |

43.4 (1.71) |

66.5 (2.62) |

85.4 (3.36) |

108.6 (4.28) |

106.6 (4.20) |

128.7 (5.07) |

1,018.6 (40.10) |

| Source: MetOffice[50] | |||||||||||||

Economy and demographics

The village provides a variety of shops and amenities for both local residents and visitors. These are largely situated in West Street and the high street. The village has numerous restaurants and three pubs with considerable trade being brought by tourists visiting the heritage sites and particularly the castle which attracted approximately 150,000 visitors in 2014.[51] Although there is still some agriculture, the previous reliance on the wool trade has been replaced by service industries catering to the visitors.[52] Both day-trippers and those staying for longer periods are catered for with shops, pubs, cafes and hotels.[53] 52.6% of people within the parish are employed which is slightly lower than the 61.9% in England and Wales and the 65.2% in Somerset.[1]

At the time of the 2011 census there were 817 people living in the parish. 13.2% were children up the age of 15 years. 52.3% were between 16 and 64 with 34.5 being 65 and older. This is an older population than in the rest of Somerset and England and Wales in general. In line with the rest of Somerset the majority of the population (95%) describes themselves as White British. 69.7% of the population live in property which they own, with 14.3% living in social rented accommodation and 12.9% privately rented. There is a higher proportion of people living alone than in other areas. The housing is fairly evenly divided between detached, semi-detached and terraced house, with 5.7% living in flats.[1]

Culture

Dunster was the birthplace of the song "All Things Bright and Beautiful" when Cecil Alexander was staying with Mary Martin, the daughter of one of the owners of Martins Bank. The nearby hill, Grabbist, was originally heather-covered before its reforestation and was described as the "Purple-headed mountain".[54]

On the evening of 1 May each year the Minehead Hobby Horse visits Dunster and is received at the Castle. A local newspaper printed in May 1863 says "The origin professes to be in commemoration of the wreck of a vessel at Minehead in remote times, or the advent of a sort of phantom ship which entered the harbour without Captain or crew. Once the custom was encouraged, but now is much neglected, and perhaps soon will fall into desuetude." Another conjecture about its origin is that the hobby horse was the ancient King of the May. The Hobby Horse tradition begins with the waking of the inhabitants of Minehead by the beating of a loud drum. The hobby horse dances its way about the town and on to Dunster Castle.[55][56]

Annually on the third Friday in August the village hosts the well known Dunster Show where local businesses and producers come together to showcase the very best that Exmoor and West Somerset has to offer. A major part of the show is the showing of livestock especially horses, cattle and sheep. The 2015 show was the 169th show.[57]

A more recent tradition (started in 1987) is Dunster by Candlelight which takes place every year on the first Friday and Saturday in December when this remarkably preserved medieval village turns its back on the present and lights its streets with candles. To mark the beginning of the festival on Friday at 5 pm, there is the Lantern Lighting Procession that starts on the Steep and continues through the village until all the lanterns in the streets have been lit. The procession of children and their families is accompanied by colourful stilt walkers in costumes who put up the lanterns.[58]

The old English Christmas tradition of burning the Ashen faggot takes place at the Luttrell Arms hotel every Christmas Eve.[59] The pub was formerly a guest house for the Abbots of Cleeve; its oldest section dates from 1443.[60]

The Priory Church of St George is predominantly 15th century with evidence of 12th- and 13th century work. It has been designated as a Grade I listed building.[61] The church was started by William de Moyon during the 11th century.[62][62] The tower was built by Jon Marys of Stogursey who received a contract from the parish in 1442. He was paid 13s 4d (approx. 67p) for each foot in height and £1 for the pinnacles. The work was completed in three years.[22] Aisles were added in 1504.[63]

The church was shared for worship between the monks of Dunster Priory and the parishioners, however this led to several conflicts between them. One outcome was the carved rood screen which divided the church in two with the parish using the west chancel and the monks the east.[20] It was restored in 1875–77 by George Edmund Street. The church has a cruciform plan with a central four-stage tower, built in 1443 with diagonal buttresses, a stair turret and single bell-chamber windows.[21]

Landmarks

Dunster, in Exmoor National Park, has many listed buildings including 200 Grade II, two Grade I and two Grade II*.

The 17th century Yarn Market is a market cross which was probably built in 1609 by the Luttrell family who were the local lords of the manor to maintain the importance of the village as a market, particularly for wool and cloth. The Yarn Market is an octagonal building constructed around a central pier. The tiled roof provides shelter from the rain.[64] The building contains a hole in one of the roof beams, a result of cannon fire in the Civil War. A bell at the top was rung to indicate the start of trading.[65]

Nearby was an older cross known as the Butter Cross which was constructed in the late 14th or early 15th century and once stood in the High Street, possibly at the southern end of the high street,[66] and was moved to its current location on the edge of the village possibly in 1825, however a drawing by J. M. W. Turner made in 1811 suggests it was in its present position by then.[67] The site where the cross now stands was leveled in 1776 by workman, paid by Henry Fownes Luttrell, and it may have been on this occasion that the cross was moved.[68] The cross has an octagonal base and polygonal shaft, however the head of the cross has been lost.[69][70] It stands on a small area of raised ground on a plinth. The socket stone is 0.85 metres (2 ft 9 in) wide and 0.5 metres (1 ft 8 in) high. The surviving shaft is 1.1 metres (3 ft 7 in) high and changes from square to octagonal as it rises.[71] There is an inscription on the northern face which says "WC, 1871, WS" recording a restoration.[70] It is in the care of English Heritage for the state and managed by the National Trust.[72][73]

Other notable buildings include the Nunnery, Dunster Watermill, Dovecote and the Priory barn, which belonged to Dunster Priory. Dunster Working Watermill (also known as Castle Mill) is a restored 18th century watermill, situated on the River Avill, close to Gallox Bridge, in the grounds of Dunster Castle. It is a Grade II* listed building.[74] The mill stands on a site where a mill was first recorded in the Domesday Book, but the present building was constructed around 1780. It closed in 1962 but was restored in 1979 and is still used to grind flour. The equipment is powered by two overshot wheels.[75][76] It is owned by the National Trust but operated as a tourist attraction by a private company.[77]

The Dovecote was probably built in the late 16th century. It has been designated as a Grade II* listed building and Scheduled Ancient Monument.[78] It is approximately 19 feet (5.8 m) high and 19 feet (5.8 m) in diameter,[79] with walls around 4 feet (1.2 m) thick.[80] In the 18th century the floor level and door were raised among several major alterations. The lower tiers of nest holes were blocked to protect against brown rats which had arrived in the Britain in 1720 and reached Somerset by 1760. A revolving ladder, known as a "potence", was installed to allow the pigeon keeper to search the nest holes more easily. In the 19th century two feeding platforms were added to the axis of the revolving ladder.[81] When the ladder was installed in the 16th century the base rests on a pin driven into a beam on the floor. The head of the pin sits in a metal cup in the base of the wooden pillar, which means the mechanism has never had to be oiled.[82] When the Dunster Castle estate was sold the dovecote was bought by the Parochial church council and opened to the public. Extensive repairs were undertaken in 1989.[83]

The Tithe Barn was originally part of a Benedictine Dunster Priory, has been much altered since the 14th century and only a limited amount of the original features survive. In the "Valor Ecclesiasticus" of 1535 the net annual income of the Dunster Tithe Barn is recorded as being £37.4s.8d (£37.23p), with £6.13s.7d ( £6.68p ) being passed on to the priory in Bath.[24] The Somerset Buildings Preservation Trust (SBPT) has co-ordinated a £550,000[84] renovation project on behalf of the Dunster Tithe Barn Community Hall Trust (DTBCHT), into a multi-purpose community hall under a 99-year lease at a pepper-corn rent, by the Crown Estate Commissioners who own the building. Funding has been obtained from the Heritage Lottery Fund and others to support the work.[85]

Conygar Tower is a folly used as a landmark for shipping. It is at the top of Conygar Hill and overlooks the village. It is a circular, 3 storey tower built of red sandstone, situated on a hill overlooking the village. It was commissioned by Henry Luttrell and designed by Richard Phelps and stands about 18 metres (59 ft) high so that it can be seen from Dunster Castle on the opposite hillside. There is no evidence that it ever had floors or a roof.[86][87] It has no strategic or military significance. The name Conygar comes from two medieval words Coney meaning rabbit and Garth meaning garden, indicating that it was once a warren where rabbits were bred for food. In 1997 a survey carried out by The Crown Estate identified cracks in the walls which were repaired in 2000.[88]

Dunster Doll Museum houses a collection of more than 800 dolls from around the world, based on the collection of the late Mollie Hardwick, who died in 1970 and donated her collection to the village memorial hall committee.[89] Established in 1971, the collection includes a display of British and foreign dolls in various costumes.[90] Thirty-two of the dolls were stolen during a burglary in 1992 and have never been recovered.[91]

Transport

Dunster railway station is on the West Somerset Heritage Railway, though the station is over a mile from the village. The station was opened on 16 July 1874 by the Minehead Railway. The line was operated by the Bristol and Exeter Railway which was amalgamated into the Great Western Railway (GWR) in 1876. The Minehead Railway was itself absorbed into the GWR in 1897.[92] A small signal box stood at the Watchet end of the platform, but was demolished in 1926 when this was extended. In 1934 a new signal box at the opposite end of the station, brought second-hand from Maerdy, was put into use when the line from Dunster to Minehead was doubled in 1934. The GWR was nationalised into British Railways in 1948 and from 1964, when goods traffic was withdrawn on 6 July, the line was run down until it was eventually closed on 4 January 1971. The line was reopened as a heritage railway operated by the West Somerset Railway on 28 March 1976. The signal box was moved to Minehead in 1977 but the goods yard is now home to the railway’s civil engineering team.[93] It is a Grade II listed building.[94]

Road access is via the A39 and A396.[95] The nearest international airports would be those at Exeter or Bristol.

Education

Dunster First School provides primary education for children from 4 to 9 years. The school is attended by 143 pupils.[96] The Grade II listed building was originally constructed in the 1870s.[97] It has since been modified and expanded since then including the construction of a heated outdoor swimming pool.[96] Middle education in the area is provided by Danesfield School and Minehead Middle School; while Secondary education in the area is provided by West Somerset College in Minehead.[98][99]

References

- "Statistics for Wards, LSOAs and Parishes — Summary Profiles" (Excel). Somerset Intelligence. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Ekwall 1960, p. 154.

- Robinson 1992, p. 50.

- Poulton-Smith 2010, p. 56.

- Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain Archived 15 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine" at Britannia. 2000.

- Adkins 1992, pp. 23-26.

- "Black Ball Camp". Arts and Humanities Data Service (AHDS). Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- Historic England. "Later prehistoric defended enclosure, Long Wood (1008255)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "MSO9087 - Long Wood Enclosure". Exmoor National Park Historic Environment Record. Exmoor National Park. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Historic England. "Longwood (36926)". PastScape. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- Historic England. "Monument No. 36851". PastScape. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Domesday Book: A Complete Translation. London: Penguin, 2003. ISBN 0-14-143994-7 p.263

- Prior 2006.

- Garnett 2003.

- "The Civil War in Somerset". Somerset County Council. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Bryant1977, p. 18.

- "Introduction to the Taunton Garrison". Taunton Garrison. Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Benedictine Priory, Dunster". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- "History of Dunster Church & Priory". Dunster Tithe Barn. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- Historic England. "Priory Church of St George, Dunster (1057646)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- Poyntz Wright 1981.

- Page, William (1911). "Houses of Benedictine monks: The priory of Dunster',". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 2. British History Online. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Dunster Tithe Barn". Everything Exmoor. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Lambert, Tim. "A History of Dunster". Local History .org. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- "Carhampton Hundred". Domesday Map. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Savage, James (1830). History of the hundred of Carhampton. Bristol. pp. 392, 581.

- Open Domesday, by Anna Powell-Smith

- "Yarn Market Dunster". Everything Exmoor. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Gathercole, Clare. "Dunster" (PDF). The Somerset Urban Archaeological Survey. Somerset County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Historic England. "Gallox Bridge (36854)". PastScape. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Burnett 1969, p. 3.

- Farr 1954, pp. 138-140.

- Foot 2006, pp. 95-101.

- "Dunster Beach" (PDF). Archaeology Data Service. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Concannon 1995, pp. 34-40.

- Concannon 1995, pp. 83-87.

- "Williton RD". A vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- "About The Exmoor National Park Authority". Exmoor National Park. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "The Historic Environment Research Framework for Exmoor" (PDF). Exmoor National Park. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Dunster and Timberscombe ward 2011". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- Mackenzie 1897.

- Dunning 1995, pp. 37-39.

- Creighton & Higham 2003, pp. 41-42.

- Dunning, pp.37–39; Creighton, pp.41–42.

- "Dunster Park and Heathlands" (PDF). English Nature. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- "About south-west England". Met Office. Archived from the original on 25 February 2006. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Water on Exmoor – Filex 7". Exmoor National Park. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Weather Stations". UKMO. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Nettlecombe Climate". UKMO. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "Latest Visitor Figures (2014)". Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Historic Dunster". Visit Dunster. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Economic History" (PDF). Victoria County History. p. 69. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Avill Valley". Everything Exmoor. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "History". Minehead Hobby Horse. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "The Minehead Hobby Horse". Minehead Online. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "The Dunster Show". Dunster Show. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Dunster by Candlight". Dunster by Candlight. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Dunster & Axmouth Ashen Faggot". Calendar Customs. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Historic England. "The Luttrell Arms Hotel (1057611)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- Historic England. "Priory Church of St George (1057646)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- Dunning 2001, p. 21.

- Dunning2007, p. 44.

- Historic England. "Yarn Market (1173428)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- Woodger 2014, p. 109.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C. (1880). "Dunster and its Lords" (PDF). The Archaeological Journal. 37: 285.

- "Dunster: The Butter Cross, St George's Church, the Castle and Conygar Tower". Tate. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- "The Butter Cross at Dunster". Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 26 September 1942. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- "History and Research: Dunster Butter Cross". English Heritage. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Historic England. "Butter Cross (1345602)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- Historic England. "Butter Cross at Dunster – ancient monument (1014409)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Butter Cross". English Heritage. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- "Butter Cross, Dunster". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Historic England. "Castle Mill and attached gateway and gates (1173447)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Castle Mill and attached gateway and gates, Dunster". Exmoor Historic Environment Record. Exmoor National Park. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Historic England. "Dunster Castle Mill (36933)". PastScape. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- "Dunster Working Watermill". National Trust. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- Historic England. "Dovecote (1057581)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Cooke, A.O. "Somerset and Devon". Book of Dovecotes. Chapter 17. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Ballard, Barbara. "Dunster Somerset". Britain Express. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Dovecote, Dunster". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Byford 1987, p. 93.

- "Dovecote 60m north of St George's Church". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Partnership resurrects 16th century tithe barn in Dunster". Crown Estate. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- "The Tithe Barn, Dunster". Somerset Building Preservation Trust. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- Holt, Jonathan (2007). Somerset Follies. Bath: Akeman Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-9546138-7-7.

- Historic England. "Conygar Tower (1057596)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- "Conygar Tower — Dunster". Everything Exmoor. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Dunster Dolls Museum". Everything Exmoor. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Dunster Museum & Doll Collection". Dunster Museum & Doll Collection. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Dunster Dolls Museum". Dunster and Timberscombe. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- MacDermot, E T (1931). History of the Great Western Railway. 2 (1863-1921) (1 ed.). London: Great Western Railway.

- Oakley, Mike (2006). Somerset Railway Stations. Bristol: Redcliffe Press. ISBN 1-904537-54-5.

- Historic England. "Dunster railway station (1057599)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- Sheet 181 Minehead and the Brendon Hills (Map). Landranger. Ordnance Survey. 2008. ISBN 978-0-319-22859-3.

- "Dunster First School". Dunster First School. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- Historic England. "Dunster County Primary School Main School Building (1057582)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "Welcome". Minehead Middle School. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "School finder". RM Education. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

Bibliography

- Adkins, Lesley and Roy (1992). A field guide to Somerset Archeology. Dovecote Press. ISBN 978-0946159949.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bryant, R.G. (1977). Dunster Village Church and Castle (3 ed.). R.G. Bryant.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burnett, E. (1969). Dunster, Somerset. Dunster Traders Association.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Byford, Enid (1987). Somerset Curiosities. The Dovecote Press. ISBN 978-0946159482.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Concannon, Bernard (1995). The History of Dunster Beach. Monkspath Books. ISBN 0-9526884-0-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creighton, Oliver; Higham, Robert (2003). Medieval Castles. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9780747805465.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dunning, Robert (1995). Somerset Castles. Somerset: Somerset Books. ISBN 978-0861832781.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dunning, Robert (2007). Somerset Churches and Chapels: Building Repair and Restoration. Halsgrove. ISBN 978-1841145921.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dunning, Robert (2001). Somerset Monasteries. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1941-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ekwall, Eilert (1960). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-869103-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farr, Grahame (1954). Somerset Harbours. London: Christopher Johnson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foot, William (2006). Beaches, fields, streets, and hills ... the anti-invasion landscapes of England, 1940. Council for British Archaeology. ISBN 1-902771-53-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garnett, Oliver (2003). Dunster Castle. National Trust. ISBN 978-1843590491.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mackenzie, James D. (1897). The Castles of England, Their Story and Structure. W. Heinemann. OCLC 504892038.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poulton-Smith, Anthony (2010). Somerset Place Names. Amberley. ISBN 9781848687820.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poyntz Wright, Peter (1981). The Parish Church Towers of Somerset, Their construction, craftsmanship and chronology 1350 - 1550. Avebury Publishing Company. ISBN 0-86127-502-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prior, Stuart (2006). The Norman Art of War: A Few Well-Positioned Castles. Tempus Publishing. ISBN 9780752436517.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Stephen (1992). Somerset Place Names. Dovecote Press. ISBN 978-1874336037.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woodger, Bev (2014). A History of Dunster. Matador. ISBN 9781783064441.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)