Hair removal

Hair removal, also known as epilation or depilation, is the deliberate removal of body hair.

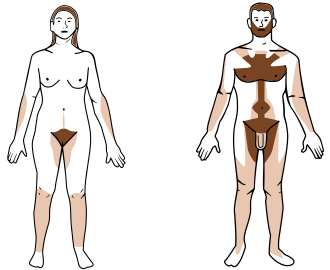

Hair typically grows all over the human body. Hair can become more visible during and after puberty and men tend to have thicker, more visible body hair than women.[1] Both men and women have visible hair on the head, eyebrows, eyelashes, armpits, pubic region, arms, and legs; men and some women also have thicker hair on their face, abdomen, back and chest. Hair does not generally grow on the lips, the underside of the hands or feet or on certain areas of the genitalia.

Hair removal may be practised for cultural, aesthetic, hygiene, sexual, medical or religious reasons. Forms of hair removal have been practised in almost all human cultures since at least the Neolithic era. The methods used to remove hair have varied in different times and regions, but shaving is the most common method.

History

In early history, hair was removed for cleanliness and fashion reasons. If the hair was cut and shaven it meant one was high class. In Ancient Egypt, besides being a fashion statement hair removal also served as a treatment for louse infestation, which was a prevalent issue in the region. Commonly, they would replace the removed hair with wigs, which were seen as easier to maintain and also fashionable. They would remove their hair using two methods: waxing and shaving. If they chose to wax they would use caramelized sugar, and if they wanted to shave, they would use an early form of the straight razor.[2]

As time went on new techniques were found to remove hair such as Laser hair removal.

Cultural and sexual aspects

Each culture of human society developed social norms relating to the presence or absence of body hair, which has changed from one time to another. Different standards of human physical appearance and physical attractiveness can apply to females and males. People whose hair falls outside a culture's aesthetic standards may experience real or perceived social acceptance problems, psychological distress and social difficulty. For example, for women in several societies, exposure in public of body hair other than head hair, eyelashes and eyebrows is generally considered to be unaesthetic, unattractive and embarrassing.[3] In Middle Eastern societies, removal of the female body hair has been considered proper personal hygiene, necessitated by local customs, for many centuries.[4][5]

With the increased popularity in many countries of women wearing fashion clothing, sportswear and swimsuits during the 20th century and the consequential exposure of parts of the body on which hair is commonly found, there has been an increase in the practice of women removing visible body hair and hirsutism, such as on legs, underarms and elsewhere.[6] In the United States, for example, the vast majority of women regularly shave their legs and armpits, while roughly half also shave hair that may become exposed around their bikini pelvic area (often termed the "bikini line").

Many men in Western cultures are accustomed to shave their facial hair, so only a minority of men reveal a beard, even though fast-growing facial hair must be shaved daily to achieve a clean-shaven or beardless appearance. Some men shave because they cannot genetically grow a "full" beard (generally defined as an even density from cheeks to neck), their beard color is genetically different from their scalp hair color, or because their facial hair grows in many directions, making a groomed or contoured appearance difficult to achieve. Some men shave because their beard growth is very excessive, unpleasant, or coarse, causing skin irritation. Some men grow a beard or moustache from time to time to change their appearance or visual style.

Some men tonsure or head shave, either as a religious practice, a fashion statement, or because they find a shaved head preferable to the appearance of male pattern baldness, or in order to attain enhanced cooling of the skull – particularly for people suffering from hyperhidrosis. A much smaller number of Western women also shave their heads, often as a fashion or political statement.

Some women also shave their heads for cultural or social reasons. In India, tradition required widows in some sections of the society to shave their heads as part of being ostracized (see Women in Hinduism § Widowhood and remarriage). The outlawed custom is still infrequently encountered mostly in rural areas. The society at large and the government are working to end the practice of ostracizing widows.[7] In addition, it continues to be common practice for men to shave their heads prior to embarking on a pilgrimage.

People may also remove some or all of their pubic hair for aesthetic or sexual reasons. This custom can be motivated by reasons of potentially increased personal cleanliness or hygiene, heightened sensitivity during sexual activity, or the desire to take on a more exposed appearance and visual appeal, or to boost self-confidence when affected by excessive hair. Moreover, unwanted or excessive hair is often removed in preparatory situations by both sexes, in order to avoid socially awkward situations. For example, unwanted or excessive hair may be removed in preparation for a sexual encounter, or before visiting a public beach.

Though traditionally in Western culture women remove body hair and men do not, some women choose not to remove hair from their bodies, either as a nonnecessity or as an act of rejection against what they regard a social stigma, while some men remove or trim their body hair, a practice that is referred to in modern society as being a part of "manscaping" (a portmanteau expression for male-specific grooming).

Fashions

The term glabrousness also has been applied to human fashions, wherein some participate in culturally motivated hair removal by depilation (surface removal by shaving, dissolving), or epilation (removal of the entire hair, such as waxing or plucking).

Although the appearance of secondary hair on parts of the human body commonly occurs during puberty, and therefore, is often seen as a symbol of adulthood, removal of this and other hair may become fashionable in some cultures and subcultures. In many modern Western cultures, men currently are encouraged to shave their beards, and women are encouraged to remove hair growth in various areas. Commonly depilated areas for women are the underarms, legs, and pubic hair. Some individuals depilate the forearms. In recent years, bodily depilation in men has increased in popularity among some subcultures of Western males.

As with any cosmetic practice, the particulars of hair removal have changed over the years. Western female depilation has been significantly influenced by the evolution of clothing in the past century. Leg and underarm shaving became popular again in some parts of Western society with the advent of off-the-shoulder dresses, higher hemlines, and transparent stockings. The reduction of the minimum acceptable standards for bodily coverage over recent years has resulted in the exposure of more flesh, giving rise to more extensive hair removal in some cultures.

Encouragement by commercial interests may be seen in advertising. At present, this has resulted in the "Brazilian waxing" trend involving the partial or full removal of pubic hair, as the thongs worn on Brazilian beaches are too small to conceal very much of it. Indeed, a culture is now emerging around "intimate shaving" and other hair removal options geared specifically toward pubic hair. (cf. bikini waxing) What was once kept a personal secret now is discussed more openly, although still in carefully non-explicit language, as advertised in magazines and on television.

For men, the practice of depilating the pubic area is commonly referred to as manscaping, even though technically this term is applicable to hair removal all over the body. Many men will try this at some point in their lives, especially for aesthetic reasons. Most men will use a razor to shave this area, however, as best practice, it is recommended to use a body trimmer to shorten the length of the hair before shaving it off completely.

Cultural and other influences

In ancient Egypt, depilation was commonly practiced, with pumice and razors used to shave.[8] In both Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, the removal of body and pubic hair may have been practiced among both men and women. It is represented in some artistic depictions of male and female nudity, examples of which may be seen in red figure pottery and sculptures like the Kouros of Ancient Greece in which both men and women were depicted without body or pubic hair. Emperor Augustus was said, by Suetonius, to have applied "hot nutshells" on his legs as a form of depilation.[9]

The majority of Muslims believe that adult removal of pubic and axillary hair, as a hygienic measure, is religiously beneficial.[10]

Baptized Sikhs are specifically instructed never to cut, shave, or otherwise remove any hair on their bodies; this is a major tenet of the Sikh faith (see Kesh).

In the clothes free movement, the term "smoothie" refers to an individual who has removed most of their hair. In the past, such practices were frowned upon and in some cases, members of clothes-free clubs were forbidden to remove their pubic hair: violators could face exclusion from the club. Enthusiasts grouped together and formed societies of their own that catered to that fashion and the fashion became more popular, with smoothies becoming a major percentage at some nudist venues.[11] The first Smoothie club (TSC) was founded by a British couple in 1991.[12] A Dutch branch was founded in 1993[13] in order to give the idea of a hairless body greater publicity in the Netherlands. Being a Smoothie is described by its supporters as exceptionally comfortable and liberating. The Smoothy-Club is also a branch of the World of the Nudest Nudist (WNN) and organizes nudist ship cruises and nudist events every month. Every year in spring the club organizes the international Smoothy days.

Other reasons

Religious reasons

Head-shaving (tonsure) is a part of some Buddhist, Christian, Muslim, Jain and Hindu traditions.[14] Buddhist and Christian monks generally undergo some form of head-shaving or tonsure during their induction into monastic life; in Thailand monks shave their eyebrows as well. Brahmin children have their heads ritualistically shaved before beginning school. The Amish religion forbids men from having mustaches, as they are associated with the military.[15]

In some parts of the Theravada Buddhist world, it is common practice to shave the heads of children. Weak or sickly children are often left with a small topknot of hair, to gauge their health and mark them for special treatment. When health improves, the lock is cut off.

In Judaism, there is no obligation to remove unwanted body hair or facial hair, unless the woman does so, she must shave whatever area she usually shaves in preparation for the Mikva, the ritual bath. Jewish men, are prohibited from using a razor to shave their beards or sideburns; and, by custom, neither men nor women may cut their hair or shave during a 30-day mourning period after the death of an immediate family member.[16][17]

The Bahá'í Faith recommends against complete and long-term head-shaving outside of medical purposes. It is not currently practiced as a law, contingent upon a future decision by the Universal House of Justice, its highest governing body. Sikhs take an even stronger stance, opposing all forms of hair removal. One of the "Five Ks" of Sikhism is Kesh, meaning "hair".[18] To Sikhs, the maintenance and management of long hair is a manifestation of one's piety.[18]

Under Muslim law (Sharia), it is recommended to keep (the beard),[19] and that which is the object of recommendation (foot, hand, back, and chest hair). A Muslim may trim or cut hair on the head. The hairs on the chest and the back may be removed. In the 9th century, the use of chemical depilatories for women was introduced by Ziryab in Al-Andalus.[20] Muslims are legislated by the Sunnah to remove underarm hair and pubic hair on a weekly basis; not doing after a 40-day period is considered sinful in the Sharia.

Ancient Egyptian priests also shaved or depilated all over daily, so as to present a "pure" body before the images of the gods.

Medical reasons

The body hair of surgical patients may be removed before surgery. In the past, this may have been achieved by shaving, but that is now considered counter-productive, so clippers or chemical depilatories may be used instead.[21] The shaving of hair has sometimes been used in attempts to eradicate lice or to minimize body odor due to accumulation of odor-causing micro-organisms in hair. Some people with trichiasis find it medically necessary to remove ingrown eyelashes. Shaving against the grain can often cause ingrown hairs.[22]

Many forms of cancer require chemotherapy, which often causes severe and irregular hair loss. For this reason, it is common for cancer patients to shave their heads even before starting chemotherapy.

In extreme situations, people may need to remove all body hair to prevent or combat infestation by lice, fleas and other parasites. Such a practice was used, for example, in Ancient Egypt.[23]

In the military

A close-cropped or completely shaven haircut is common in military organizations. In field environments, soldiers are susceptible to infestation of lice, ticks, and fleas. In addition, short hair is also more difficult for an enemy to grab hold of in hand-to-hand combat, and short hair makes fitting military gas masks and helmets easier.

The practice serves to cultivate a group-oriented environment through the process of removing exterior signs of individuality. In many militaries head-shaving is mandatory for males when beginning their training. However, even after the initial recruitment phase, when head-shaving is no longer required, many soldiers maintain a completely or partially shaven hairstyle (such as a "high and tight", "flattop" or "buzz cut") for personal convenience and an exterior symbol of military solidarity. Head-shaving is not required and is often not allowed of females in military service, although they must have their hair cut or tied to regulation length.

Armies may also require males to maintain clean-shaven faces as facial hair can prevent an air-tight seal between the face and breathing or safety equipment, such as a pilot's oxygen mask, a diver's mask, or a soldier's gas mask.

In sport

It is a common practice for professional footballers (soccer) and road cyclists to remove leg hair for a number of reasons. In the case of a crash or tackle, the absence of the leg hair means the injuries (usually road rash or scarring) can be cleaned up more efficiently, and treatment is not impeded. Professional cyclists, as well as professional footballers, also receive regular leg massages, and the absence of hair reduces the friction and increases their comfort and effectiveness.

It is also common for competitive swimmers to shave the hair off their legs, arms, and torsos, to reduce drag and provide a heightened "feel" for the water by removing the exterior layer of skin along with the body hair.[24] Some professional soccer players also shave their legs. One of the reasons is that they are required to wear shin guards and in case of a skin rash the affected area can be treated more efficiently.

As punishment

In some situations, people's hair is shaved as a punishment or a form of humiliation. After World War II, head-shaving was a common punishment in France, the Netherlands, and Norway for women who had collaborated with the Nazis during the occupation, and, in particular, for women who had sexual relations with an occupying soldier.[25]

In the United States, during the Vietnam War, conservative students would sometimes attack student radicals or "hippies" by shaving beards or cutting long hair. One notorious incident occurred at Stanford University, when unruly fraternity members grabbed Resistance founder (and student-body president) David Harris, cut off his long hair, and shaved his beard.

During European witch-hunts of the Medieval and Early Modern periods, alleged witches were stripped naked and their entire body shaved to discover the so-called witches' marks. The discovery of witches' marks was then used as evidence in trials.

Head shaving during present times is also used as a form of payment for challenges or dares lost involving the removal of all body hair.

Inmates have their head shaved upon entry at certain prisons.

Forms of hair removal

Depilation is the removal of the part of the hair above the surface of the skin. The most common form of depilation is shaving or trimming. Another option is the use of chemical depilatories, which work by breaking the disulfide bonds that link the protein chains that give hair its strength.

Epilation is the removal of the entire hair, including the part below the skin. Methods include waxing, sugaring, epilators, lasers, threading, intense pulsed light or electrology. Hair is also sometimes removed by plucking with tweezers.

Hair removal methods

Many products in the market have proven fraudulent. Many other products exaggerate the results or ease of use.

Depilation methods

"Depilation", or temporary removal of hair to the level of the skin, lasts several hours to several days and can be achieved by

- Shaving or trimming (manually or with electric shavers)

- Depilatories (creams or "shaving powders" which chemically dissolve hair)

- Friction (rough surfaces used to buff away hair)

Epilation methods

"Epilation", or removal of the entire hair from the root, lasts several days to several weeks and may be achieved by

- Tweezing (hairs are tweezed, or pulled out, with tweezers or with fingers)

- Waxing (a hot or cold layer is applied and then removed with porous strips)

- Sugaring (hair is removed by applying a sticky paste to the skin in the direction of hair growth and then peeling off with a porous strip)

- Threading (also called fatlah or khite in Arabic, or band in Persian) in which a twisted thread catches hairs as it is rolled across the skin

- Epilators (mechanical devices that rapidly grasp hairs and pull them out).

- Drugs that directly attack hair growth or inhibit the development of new hair cells. Hair growth will become less and less until it finally stops; normal depilation/epilation will be performed until that time. Hair growth will return to normal if use of product is discontinued.[26] Products include the following:

- The pharmaceutical drug Vaniqa, with the active ingredient eflornithine hydrochloride, inhibits the enzyme ornithine decarboxylase, preventing new hair cells from producing putrescine for stabilizing their DNA.

- Antiandrogens, including spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, flutamide, bicalutamide, and finasteride, can be used to reduce or eliminate unwanted body hair, such as in the treatment of hirsutism.[27][28][29][30] Although effective for reducing body hair, antiandrogens have little effect on facial hair.[31] However, slight effectiveness may be observed, such as some reduction in density/coverage and slower growth.[32] Antiandrogens will also prevent further development of facial hair, despite only minimally affecting that which is already there. With the exception of 5α-reductase inhibitors such as finasteride and dutasteride,[27][33] antiandrogens are contraindicated in men due to the risk of feminizing side effects such as gynecomastia as well as other adverse reactions (e.g., infertility), and are generally only used in women for cosmetic/hair-reduction purposes.[34]

Permanent hair removal

For over 130 years, electrology has been in use in the United States. It is approved by the FDA. This technique permanently destroys germ cells responsible for hair growth by way of insertion of a fine probe in the hair follicle and the application of a current adjusted to each hair type and treatment area. Electrology is the only permanent hair removal method recognized by the FDA.[35]

Permanent hair reduction

- Laser hair removal (lasers and laser diodes): Laser hair removal technology became widespread in the US and many other countries from the 1990s onwards. It has been approved in the United States by the FDA since 1997. With this technology, light is directed at the hair and is absorbed by dark pigment, resulting in the destruction of the hair follicle. This hair removal method sometimes becomes permanent after several sessions. The number of sessions needed depends upon the amount and type of hair being removed. Equipment for performing laser hair removal at home has become available in recent years.

- Intense pulsed light (IPL)

- Diode epilation (high energy LEDs but not laser diodes)

Clinical comparisons of effectiveness

A 2006 review article in the journal "Lasers in Medical Science" compared intense pulsed light (IPL) and both alexandrite and diode lasers. The review found no statistical difference in effectiveness, but a higher incidence of side effects with diode laser-based treatment. Hair reduction after 6 months was reported as 68.75% for alexandrite lasers, 71.71% for diode lasers, and 66.96% for IPL. Side effects were reported as 9.5% for alexandrite lasers, 28.9% for diode lasers, and 15.3% for IPL. All side effects were found to be temporary and even pigmentation changes returned to normal within 6 months.[36]

A 2006 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that alexandrite and dioded lasers caused 50% hair reduction for up to 6 months, while there was no evidence of hair reduction from intense pulsed light, neodymium-YAG or ruby lasers.[37]

Experimental or banned methods

- Photodynamic therapy for hair removal (experimental)

- X-ray hair removal is an efficient, and usually permanent, hair removal method, but also causes severe health problems, occasional disfigurement, and even death.[38] It is illegal in the United States.

Doubtful methods

Many methods have been proposed or sold over the years without published clinical proof they can work as claimed.

- Electric tweezers

- Transdermal electrolysis

- Transcutaneous hair removal

- Photoepilators

- Microwave hair removal

- Foods and dietary supplements

- Non-prescription topical preparations (also called "hair inhibitors", "hair retardants", or "hair growth inhibitors")

Advantages and disadvantages

There are several disadvantages to many of these hair removal methods.

Hair removal can cause some issues: skin inflammation, minor burns, lesions, scarring, ingrown hairs, bumps, and infected hair follicles.

Some removal methods are not permanent, can cause medical problems and permanent damage, or have very high costs. Some of these methods are still in the testing phase and have not been clinically proven.

One issue that can be considered an advantage or a disadvantage depending upon an individual's viewpoint, is that removing hair has the effect of removing information about the individual's hair growth patterns due to genetic predisposition, illness, androgen levels (such as from pubertal hormonal imbalances or drug side effects), and/or gender status.

In the hair follicle, stem cells reside in a discrete microenvironment called the bulge, located at the base of the part of the follicle that is established during morphogenesis but does not degenerate during the hair cycle. The bulge contains multipotent stem cells that can be recruited during wound healing to help the repair of the epidermis.[39]

See also

|

|

References

- Citations

- Shellow, Victoria (2006) Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History, Greenwood Publishing Group. p.67. (ISBN 0-313-33145-6)

- Bhargava, Amber (November 26, 2012). "Beauty and the Geek: The Engineering Behind Laser Hair Removal". Illumin.

- Heinz Tschachler, Maureen Devine, Michael Draxlbauer; The EmBodyment of American Culture; pp 61–62; LIT Verlag, Berlin-Hamburg-Münster; 2003; ISBN 3-8258-6762-5.

- Kutty, Ahmad (September 13, 2005) "Islamic Ruling on Waxing Unwanted Hair" Archived 2008-02-13 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved March 29, 2006

- Irvin Cemil Schick, "Some Islamic Determinants of Dress and Personal Appearance in Southwest Asia," Khil’a 3 (2007–2009 [2011]), 25–53.

- "Who decided women should shave their legs and underarms?". The Straight Dope. 1991-02-06. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- Shunned from society, widows flock to city to die, 2007-07-05, CNN.com, Retrieved 2007-07-05

- Boroughs, Michael; Cafri, Guy; Thompson, J. Kevin (2005). "Male Body Depilation: Prevalence and Associated Features of Body Hair Removal". Sex Roles. 52 (9–10): 637–644. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-3731-9.

- The Twelve Caesars, Aug. 68.

- "Shaving Pubic Hair". Understanding Islam. 10 February 1999.

- "smooth naturists & nudists - Smoothies". Euro Naturist. Archived from the original on 2005-05-08.

- World of the Nudest Nudist, beauty of the shaved body Archived August 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "World of the Nudest Nudist - home of the barest naturists". Wnn.nu. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- Karthikeyan, Kaliaperumal (Jan–Jun 2009). "Tonsuring: Myths and Facts". International Journal of Trichology. MedKnow Publications. 1 (1): 33–34. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.51927. ISSN 0974-9241. PMC 2929550. PMID 20805974 – via Academic Search Complete.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "The Amish". bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- "Jewish Practices & Rituals: Beards". Jewish Virtual Library. December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- "Death & Bereavement in Judaism: Death and Mourning". Jewish Virtual Library. December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- Trüeb, Ralph (January–March 2017). "From Hair in India to Hair India". International Journal of Trichology. MedKnow Publications. 9 (1): 1–6. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_10_17. PMC 5514789. PMID 28761257.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "Back Shaving in Sharia". Sharia. Muslim. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- van Sertima, Ivan (1992). The Golden Age of the Moor. Transaction Publishers. p. 267. ISBN 978-1-56000-581-0. OCLC 123168739.

- Ortolon, Ken (April 2006). "Clip, Don't Nick: Physicians Target Hair Removal to Cut Surgical Infections". Texas Medicine. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- Bailey, Ryan (June 6, 2011). "Does going 'against the grain' give you a better shave?". Men's Health. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Kenawy, Mohamed; Abdel-Hamid, Yousrya (January 2015). "Insects in Ancient (Pharaonic) Egypt: A Review of Fauna, Their Mythological and Religious Significance and Associated Diseases". Egyptian Academic Journal of Biological Sciences. A, Entomology. Egyptian Society of Biological Sciences. 8 (1): 15–32. doi:10.21608/eajbsa.2015.12919. ISSN 1687-8809 – via Academic Search Complete.

- Kostich, Alex (2001-05-15). "Why Swimmers Shave Their Bodies". active.com. Active network. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Richard Vinen (1 December 2007). The Unfree French: Life Under the Occupation. Yale University Press. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-300-12601-3.

- "Eflornithine Monohydrate Chloride (Eflornithine 11.5% cream)". nhs.uk. NHS. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1004–1005. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- Catherine B. Niewoehner (2004). Endocrine Pathophysiology. Hayes Barton Press. pp. 290–. ISBN 978-1-59377-174-4.

- Tommaso Falcone; William W. Hurd (22 May 2013). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery: A Practical Guide. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-1-4614-6837-0.

- Erem C (2013). "Update on idiopathic hirsutism: diagnosis and treatment". Acta Clin Belg. 68 (4): 268–74. doi:10.2143/ACB.3267. PMID 24455796.

- Rachel Ann Heath (1 January 2006). The Praeger Handbook of Transsexuality: Changing Gender to Match Mindset. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-0-275-99176-0.

- Heinz Duthel (26 July 2013). Kathoey Ladyboy: Thailand's Got Talent. BoD – Books on Demand. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-3-7322-3663-3.

- Ulrike Blume-Peytavi; David A. Whiting; Ralph M. Trüeb (26 June 2008). Hair Growth and Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-3-540-46911-7.

- Alan R. Shalita; James Q. Del Rosso; Guy Webster (21 March 2011). Acne Vulgaris. CRC Press. pp. 200–. ISBN 978-1-61631-009-7.

- "Removing hair safely". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- Toosi, Parviz (2006-04-01). "A comparison study of the efficacy and side effects of different light sources in hair removal". Lasers in Medical Science. 21 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1007/s10103-006-0373-2. PMID 16583183.

- Haedersdal, Merete; Gøtzsche, Peter C (2006-10-18). "Laser and photoepilation for unwanted hair growth". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD004684. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004684.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 17054211.

- Helen Bickmore (2004). Milady's Hair Removal Techniques: A Comprehensive Manual. ISBN 978-1401815554. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- Blanpain, C; Fuchs, E (2006). "Epidermal Stem Cells of the Skin". Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 22: 339–73. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104357. PMC 2405915. PMID 16824012.

Further reading

- Aldraibi MS, Touma DJ, Khachemoune A (January 2007). "Hair removal with the 3-msec alexandrite laser in patients with skin types IV-VI: efficacy, safety, and the role of topical corticosteroids in preventing side effects". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 6 (1): 60–6. PMID 17373163.

- Alexiades-Armenakas M (2006). "Laser hair removal". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 5 (7): 678–9. PMID 16865877.

- Eremia S, Li CY, Umar SH, Newman N (November 2001). "Laser hair removal: long-term results with a 755 nm alexandrite laser". Dermatologic Surgery. 27 (11): 920–4. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.01074.x. PMID 11737124.

- Herzig, Rebecca M. Plucked: A History of Hair Removal. New York: New York University Press, 2015.

- McDaniel DH, Lord J, Ash K, Newman J, Zukowski M (June 1999). "Laser hair removal: a review and report on the use of the long-pulsed alexandrite laser for hair reduction of the upper lip, leg, back, and bikini region". Dermatologic Surgery. 25 (6): 425–30. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08118.x. PMID 10469087.

- Wanner M (2005). "Laser hair removal". Dermatologic Therapy. 18 (3): 209–16. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.05020.x. PMID 16229722.

- Warner J, Weiner M, Gutowski KA (June 2006). "Laser hair removal". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 49 (2): 389–400. doi:10.1097/00003081-200606000-00020. PMID 16721117.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hair removal. |