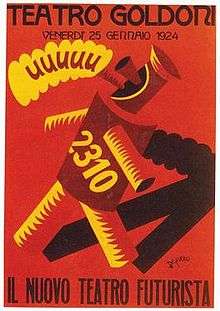

Fortunato Depero

Fortunato Depero (March 30, 1892 – November 29, 1960) was an Italian futurist painter, writer, sculptor and graphic designer.

Biography

Although born in Fondo or in the neighboring village of Malosco, according to other sources (in the Italian Trentino region),[1] Depero grew up in Rovereto and it was here he first began exhibiting his works, while serving as an apprentice to a marble worker. It was on a 1913 trip to Florence that he discovered a copy of the paper Lacerba and an article by one of the founders of the futurism movement, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Depero was inspired, and in 1914 moved to Rome and met fellow futurist Giacomo Balla. It was with Balla in 1915 that he wrote the manifesto Ricostruzione futurista dell’universo ("Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe") which expanded upon the ideas introduced by the other futurists. In the same year he was designing stage sets and costumes for a ballet.

In 1919 Depero founded the House of Futurist Art in Rovereto, which specialised in producing toys, tapestries and furniture in the futurist style. In 1925 he represented the futurists at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts), and presented a Futurist Hall at the Monza Biennial.[2] In 1927 he created for the publisher Dinamo-Azari of Milan one of his most famous objects—the so-called "bolted book" entitled Depero futurista to celebrate the fourteenth anniversary of Futurism.[3]

1928 saw Depero move to New York City, where he experienced a degree of success, doing costumes for stage productions and designing covers for magazines including MovieMaker, The New Yorker and Vogue, among others. He also dabbled in interior design during his stay, working on two restaurants which were later demolished to make way for the Rockefeller Center. He also did work for the New York Daily News and Macy's, and built a house on 23rd Street. In 1930 he returned to Italy.

In the 1930s and 40s Depero continued working, although due to futurism being linked with fascism, the movement started to wane. The artistic development of the movement in this period can mostly be attributed to him and Balla. One of the projects he was involved in during this time was Dinamo magazine, which he founded and directed. After the end of the Second World War, Depero had trouble with authorities in Europe and in 1947 decided to try New York again. This time he found the reception not quite as welcoming. One of his achievements on his second stay in the United States was the publication of So I Think, So I Paint, a translation of his autobiography initially released in 1940: Fortunato Depero nelle opere e nella vita (literally, Fortunato Depero, his works and his life). From the winter of 1947 to late October 1949 Depero lived in a cottage in New Milford, Connecticut, relaxing and continuing with his long-standing plans to open a museum. His host was William Hillman, an associate of the then-President, Harry S. Truman.

After New Milford, Depero returned to Rovereto, where he would live out his days. In August 1959 Galleria Museo Depero opened, fulfilling one of his long-term ambitions. On November 29, 1960, after being ill with diabetes and spending the last two years unable to paint due to hemiparesis, Depero died age 68.

Many of his works are featured in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto (MART).[4] The Casa d'Arte Futurista Depero, Italy's only museum dedicated to the Futurist movement, containing 3,000 objects, is now one of MART's venues. Closed for many years for extensive refurbishment, the Casa d'Arte Futurista Depero reopened in 2009.[5]

Exhibitions

From February 22 until June 28, 2014, the Center for Italian Modern Art, exhibited Depero's work which engaged in dialogues with Dada and Metaphysical Painting, Espirit Nouveau, and Art Deco.[6]

Writings

- So I think, so I paint: Ideologies of an Italian self-made painter, Mutilati e Invalidi, Trento, 1947 ASIN: B0007JG8YG

References

- Hangar Design Group (n.d.). "Fortunato Depero". Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- "Guido Marangoni and the Biennials of Monza, 1923–1927, Design before Design, Villa Reale di Monza – ARTDIRECTORY". Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- "The Bolted Book: A New Facsimile".

- Mart, the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto

- "Casa d'Arte Futurista Depero". "Quando vivrò di quello che ho pensato ieri, comincerò ad avere paura di chi mi copia" FD. Il Museo di Arte Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto ("Mart"). Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- "Fortunato Depero: annual installation 22 February – 28 June 2014". Center for Italian Modern Art, New York.

- Belli, G., Depero futurista: Rome-Paris-New York: 1915–1932, exhibithion catalogue, The Wolfsonian Florida International University, Miami Beach, Florida. Milan: Skira, 1999.

- Chiesa, L., “Transnational Multimedia: Fortunato Depero’s Impressions of New York City (1928–1930),” California Italian Studies, 1, 2010.

- Ewing, H., ed., Fortunato Depero, exhibition catalogue, Center for Italian Modern Art, New York, 2014.

- Greene, V., ed., Italian Futurism 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe, exhibition catalogue, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2014.

- Troy, Virginia Gardner, "Stitching Modernity: The Textile Work of Fortunato Depero," Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 1, January 2015, p. 24–33.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fortunato Depero |