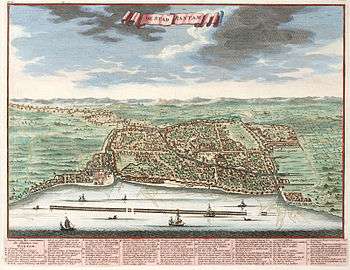

Banten (town)

Banten, also written as Bantam, is a port town near the western end of Java, Indonesia. It has a secure harbour at the mouth of Banten River, a navigable passage for light craft into the island's interior. The town is close to the Sunda Strait through which important ocean-going traffic passes between Java and Sumatra. Formerly Old Banten was the capital of a sultanate in the area, was strategically important and a major centre for trade.

History

In the 5th century Banten was part of the Tarumanagara kingdom. The Lebak relic inscriptions, found in lowland villages on the edge of Ci Danghiyang, Munjul, Pandeglang, Banten, were discovered in 1947 and contains 2 lines of poetry with Pallawa script and Sanskrit language. The inscriptions mentioned the courage of king Purnawarman. After the collapse of the kingdom Tarumanagara following an attack by the Srivijaya empire, power in western Java fell to the Kingdom of Sunda. The Chinese source, Chu-fan-chi, written c. 1200, Chou Ju-kua mentioned that in the early 13th Century, Srivijaya still ruled Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, and western Java (Sunda). The source identifies the port of Sunda as strategic and thriving, pepper from Sunda being among the best in quality. The people worked in agriculture and their houses were built on wooden poles (rumah panggung). However, robbers and thieves plagued the country.[1] It is highly possible that the port of Sunda mentioned by Chou Ju-kua referred to the port of Banten.

According to Portuguese explorer, Tome Pires, in the early 16th century the port of Bantam (Banten) was one of the important ports of the Kingdom of Sunda along with the ports of Pontang, Cheguide (Cigede), Tangaram (Tangerang), Calapa (Sunda Kelapa) and Chimanuk (estuarine of Cimanuk river).[2]

As a trading city Bantam received an influx of Islamic influence in the early 16th century. Later in the 16th century Bantam became the seat of the powerful Banten Sultanate.

English Bantam

The English East India Company began to send ships to the East Indies around 1600 and established a permanent trading post at Bantam in 1603, as did the Dutch also. In 1613, John Jourdain was appointed as Chief Factor there, holding the administrative post until 1616, apart from a few months of 1615, when Thomas Elkington was Chief Factor; he was succeeded in 1616 by George Berkley, but from 1617 until 1630 the factory was under a chosen President. From 1630 until 1634 a succession of Agents were appointed annually, but from 1634 the series of Presidents resumed until 1652. Aaron Baker (1610-1683) served for twenty years as President of Bantam, as is recorded on his mural monument in Dunchideock parish church, Devon. In the thirty years following 1603, the trading factories established by the English on the Coromandel Coast of India, such as those at Machilipatnam (estd. 1611) and Fort St. George (estd. 1639), reported to Bantam.[3]

During the 17th century, the Portuguese and the Dutch fought for control of Bantam. Eventually, the fact that the Dutch found they could control their Batavia trading factory, established in 1611, more thoroughly than Bantam may have contributed to the decline of the English trading post.

The town today

Today, Banten is a small local seaport, in the economic shadow of the neighbouring port of Merak to the west and Jakarta to the east. There is a significant Chinese presence in the community.

In fiction

South-Bantam or Bantan-Kidoel or Lebak was the place where the eponymous character in Multatuli's novel Max Havelaar acted as the assistant-resident.

See also

- Old Banten

- East India Company

- English overseas possessions

- Dutch East India Company in Indonesia

References

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Banten. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Banten. |

- Drs. R. Soekmono (1973). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2, 2nd ed. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 60.

- SJ, Adolf Heuken (1999). Sumber-sumber asli sejarah Jakarta, Jilid I: Dokumen-dokumen sejarah Jakarta sampai dengan akhir abad ke-16. Cipta Loka Caraka. p. 34.

- N. S. Ramaswami, Fort St. George, Madras, Pub. No. 49, Tamilnadu State Department of Archaeology (T.N.S.D.A.), Madras, First Edition 1980

Works cited

- Witton, Patrick (2003). Indonesia. Melbourne: LonelyPlanet. pp. 164–165. ISBN 1-74059-154-2.