Dead Space (video game)

Dead Space is a 2008 survival horror video game, developed by EA Redwood Shores and published by Electronic Arts for PlayStation 3, Xbox 360 and Microsoft Windows. The debut entry in the Dead Space series, it released North America, Europe and Australia. Set on a mining spaceship overrun by deadly monsters called necromorphs released following the discovery of an artifact called the Marker, the player controls engineer Isaac Clarke as he navigates the spaceship and fights the necromorphs while struggling with growing psychosis. Gameplay has Isaac exploring different areas through its chapter-based narrative, solving environmental puzzles and finding ammunition and equipment to survive.

| Dead Space | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | EA Redwood Shores |

| Publisher(s) | Electronic Arts |

| Director(s) | Michael Condrey Bret Robbins |

| Producer(s) |

|

| Designer(s) | Paul Mathus |

| Programmer(s) | Steve Timson |

| Artist(s) | Ian Milham |

| Writer(s) | Warren Ellis Rick Remender Antony Johnston |

| Composer(s) | Jason Graves |

| Series | Dead Space |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation 3 Xbox 360 Microsoft Windows |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Survival horror |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Dead Space was pitched in early 2006, with an early prototype running on Xbox. Creator Glen Schofield wanted to make the most frightening horror game he could imagine, drawing inspiration from the video game Resident Evil 4 and films including Event Horizon and Solaris. The team pushed for innovation and realism in their design, ranging from procedural enemy placement to removing HUD elements. The sound design was a particular focus during production, with the score by Jason Graves designed to evoke tension and unease.

The game was announced in 2007, and formed part of a push by Electronic Arts to develop new intellectual properties. Though making a weak sales debut alongside their other 2008 titles, the game eventually sold one million copies worldwide. Critics praised its atmosphere, gameplay and sound design. It won and was nominated for multiple industry awards, and has been ranked by journalists as one of the greatest video games of all time. It spawned two direct sequels (Dead Space 2, Dead Space 3), and inspired several spin-off titles and related media including a comic prequel and animated film.

Gameplay

Dead Space is a science fiction survival horror video game; players take on the role of Isaac Clarke, controlling him through a third-person perspective. Players navigate the spaceship Ishimura, completing objectives given to Isaac during the narrative, solving physics-based puzzles within the environment, and fighting monsters dubbed necromorphs.[1][2][3] In some parts of the ship that have decompressed, Isaac must navigate the vacuum. While in the vacuum, Isaac has a limited air supply which can be replenished by finding air tanks within the environment. Some areas are subject to zero-g, with both Isaac and specific enemy types able to jump between surfaces and these areas having dedicated puzzles.[2][4] During exploration of the Ishimura, Isaac finds ammunition for his weapons, health pickups, and Nodes that are used to both unlock special doors and upgrade weapons and Isaac's suit. At points in the ship, Isaac can access a store to buy supplies and ammunition.[5][6] Isaac can use a navigation line, projected onto the floor on command, to find the next mission objective.[7]

Isaac has access from the start to a basic stomp, which can be used to break supply crates and attack enemies; and a melee punch which can kill smaller enemies and knock back larger ones. Two more abilities unlocked during the game are Kinesis, which can move or pull objects in the environment; and Stasis, which slows movement for a limited time.[7] All gameplay displays are diegetic, appearing in-world as holographic projections; Isaac's health and energy levels are displayed on his back of his suit, ammunition count appears when weapons are raised, and all information displays—control prompts, pick-ups, video calls, the game map, inventory, store fronts—appear as holographic displays. While the player is in menus, time in the game does not pause.[6][7]

While exploring, Isaac must fight necromorphs, which appear from vents, or awaken from corpses scattered through the ship.[3] The various types of necromorphs have different abilities and require altered tactics to defeat.[1] Depending on how they are wounded, necromorphs can adopt new stances and tactics such as sprouting new limbs or giving birth to new enemies in the process.[2] Isaac can access multiple weapons to combat the necromorphs, which can only be killed by cutting off their limbs.[3] To do this, Isaac uses weapons designed for cutting; the starting weapon is picked up during the first level, while others can be crafted using blueprints discovered in different levels.[8][9] Workbenches found in levels can be used by Isaac to increase the power or other attributes of his weapons and suit.[10] Beating the game unlocks New Game+, which gives Isaac access to a new outfit, extra currency and crafting equipment, and new video and audio logs. It also unlocks a higher difficulty setting.[11][12]

Synopsis

Setting and characters

Dead Space is set in the year 2508, during a time where humanity has spread through the universe and harvests resources from barren planets using ships dubbed "Planetcrackers" following their near-extinction on Earth due to resource shortages. The oldest Planetcracker is the USG Ishimura, which is performing an illegal mining operation on the planet Aegis VII.[13][14] The backstory reveals that Aegis VII was the home of a "Red Marker", a manmade copy of the original alien Marker monolith discovered on Earth; attempts to weaponise the Marker and its copies led to the creation of a virus-like organism that infected corpses and transformed them into monsters called necromorphs. Two key factions in Dead Space are the Earth Government, which created and then hid the Red Markers; and Unitology, a religious movement that worships the Markers, founded in the name of original researcher Michael Altman.[15][16]

In the events leading up to Dead Space, the colony on Aegis VII discovers the Red Marker hidden there. Following its discovery and the Ishimura's arrival, the colonists and then ship crew begin suffering from hallucinations and eventually severe mental illness, climaxing in the emergence of the necromorphs. By the time the maintenance ship Kellion arrives, the entire Aegis VII colony and all but a few of the Ishimura crew have been killed or turned into necromorphs.[14][17]

The game's protagonist is Isaac Clarke, an engineer who travels on the Kellion to find out what happened to his girlfriend Nicole Brennan, the Ishimura's senior medical officer.[18][19] Aboard the Kellion with Isaac are chief security officer Zach Hammond, and computer technician Kendra Daniels—unknown to the Kellion crew, Kendra is a Earth government agent sent to control the situation. Other characters encountered by Isaac on the Ishimura are Challus Mercer, an insane scientist who believes the necromophs are humanity's ascended form; Dr. Terrence Kyne, a survivor who wants to return the Marker to Aegis VII; and Nicole, who mysteriously communicates with and appears to Isaac at various points through the ship.[16][18]

Plot

Isaac arrives at Aegis VII on the Kellion with Kendra and Hammond; during the journey, Isaac has been repeatedly watching a video message from Nicole. A docking malfunction crashes the Kellion into the Ishimura's landing bay, and all the Kellion crew but Isaac, Kendra, and Hammond are killed by necromorphs when the ship's quarantine is broken. Isaac navigates the ship, restoring systems and finding parts to repair their ship so they can escape. They almost succeed, but the Kellion is destroyed in a further malfunction. During these events, all three survivors begin experiencing escalating symptoms of psychosis and dementia, ranging from hallucinations to paranoia.

During his exploration, Isaac learns through audio and video logs about the incident. The Ishimura's illegal mining operation on Aegis VII, which was designated off-limits by the Earth Government, was meant to find the Red Marker for the Church of Unitology. The Aegis VII colony was almost entirely wiped out by mass psychosis triggered by the Marker, causing both killings and suicides. The Marker was brought aboard the Ishimura along with survivors and bodies from the colony. A combination of the Marker's influence, factional fighting and the emerging necromorph invasion killed nearly everyone aboard. Two survivors Isaac comes across are Terrence Kyne, who has abandoned his belief in Unitology; and Challus Mercer, who has gone insane and worships the necromorphs.

Despite Isaac's efforts, Hammond is killed by a necromorph, and Mercer allows himself to be transformed by them. Another ship, the Valor, arrives and is infected through an Ishimura escape pod containing a necromorph, but records show it was dispatched to remove all traces of the incident. Kendra kills Kyne before revealing her Earth Government allegiance, as Kyne threatened the Marker and the necromorphs' controlling "Hive Mind". The Marker was a copy of an ancient alien artefact found on Earth, left on Aegis VII as part of an experiment that Earth wants retrieved. Reunited with Nicole, Isaac sabotages Kendra's attempt to escape the Ishimura, then returns the Marker to Aegis VII, neutralising the necromorphs and initiating Aegis VII's collapse.

Kendra retrieves the Marker and reveals the truth to Isaac; his encounters with Nicole were hallucinations created by the Marker to return it to the Hive Mind, as Nicole's message ends with her committing suicide to avoid becoming a necromorph. Kendra is then killed by the awoken Hive Mind before she can escape with the Marker. After killing the Hive Mind, Isaac leaves on Kendra's shuttle as Aegis VII is destroyed. In the shuttle, a distraught Isaac mourns Nicole, then is attacked by a violent hallucination of her.

Production

Development

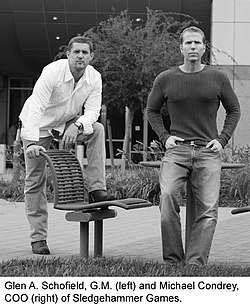

Dead Space was the creation of Glen Schofield, at the time working at EA Redwood Shores. Schofield wanted to create what he felt would be the most frightening horror game possible. His concept drew influence from the Resident Evil series, particularly the recently-released Resident Evil 4, and the Silent Hill series.[22] EA Redwood Shores had established itself as a studio for licensed game properties, and the team saw it as an opportunity to branch out into original properties, establishing themselves as "a proper game studio" according to co-producer Steve Papoutsis.[23] During this early stage, the game was known as "Rancid Moon".[20] Dead Space was described as a project multiple staff at Redwood Shores wanted to work on for many years.[20] Co-director Michael Condrey described it in 2014 as a grassroots-style project where the team were eager to prove themselves, but not expecting the game to become anything large-scale.[21] When they pitched the game to parent company Electronic Arts in early 2006, they were given three months to create a prototype.[24]

As to get a playable concept ready within that time, the prototype was developed the original Xbox hardware. The team decided it would be better to get something playable before working out how to make the game work on next-generation hardware. Their twin approaches of early demos and aggressive internal promotion ran counter to Electronic Arts practises for new games at the time.[24] Electronic Arts eventually approved the game after seeing a vertical slice build of the game equivalent to one level, by which time all the basic gameplay elements had been settled on.[20][24] According to co-producer Chuck Beaver, this pre-greenlight work lasted 18 months. After approval and using their experience creating the vertical slice, the team built eleven more levels in just ten months.[24] The team reused the game engine they designed for The Godfather, which was chosen due to being tailored for their development style and supporting the necessary environmental effects, and implemented the Havok physics engine.[23][25] While Electronic Arts wanted details on its prospective budget and sales, Schofield pushed for a focus on quality before anything else.[26]

Game design

Schofield wanted to create a game that ran counter to Electronic Art's usual output.[27] To help guide the team, Schofield often described Dead Space as "Resident Evil in space".[22] There are different accounts as to the game's relation to the System Shock series. Condrey said that Dead Space was only influenced by both System Shock and System Shock 2.[13] Co-designer Ben Wanat stated that the team were originally planning a third entry in the System Shock series and played through the originals for reference, but when Resident Evil 4 released they decided to make their own intellectual property based around its gameplay.[28] While greatly influenced by Resident Evil 4, Schofield wanted to make the game more active, as the necessity to stop and shoot in Resident Evil 4 often broke his immersion.[22] The gameplay balance was aimed between the faster pace of third-person shooters and the slow pace of many horror game protagonists.[29] Resource management underwent constant tuning and balancing to make it tense but not unfair or frustrating.[30]

Immersion was a core element of the game, with any HUD elements being in-universe and story sequences like cutscenes and audio or video logs playing in real-time. In addition, the standard HUD elements were incorporated into the environment with suitable contextual or overt in-game explanations.[22][31][19] In the team's opinion, the setting was better realised and conveyed as a side effect of this approach.[30] A quick turn option was both implemented and removed several times during production before eventually removing it as mapping it to the last available controller buttons was causing test players to turn by accident during dangerous situations.[25] The Microsoft Windows version's control scheme went through several different configurations, with the team wanting the best possible for mouse and keyboard.[30]

One of the founding gameplay principles was "strategic dismemberment", the focus on cutting off limbs to kill enemies that distinguished Dead Space from the majority of other shooters which placed focus on headshots or allowed volleys of fire against enemies. Because of this, weapon accuracy and enemy behaviour were adjusted around this concept.[23][32] An instance of this was how enemies reacted to a traditional headshot, becoming enraged and charging at the player rather than being instantly killed.[32] A two-person co-op multiplayer option was prototyped over a three month period, but ended up cut so the team could focus on making a polished single-player experience.[27]

A procedural element was created for enemy placement, so that enemies would appear at random points within a room, not allowing players to easily memorise and counterattack against patterns.[33] There was a mechanism for controlling where enemies would spawn from places like vents depending on the player's position. One gameplay sequence, where Isaac is ambushed and dragged down a hallway by a large tentacle, stalled development for a month. The team initially planned it as an instant death to be avoid, then changed it to be an interactive one that Isaac had to escape. A dedicated set of mechanics and animations had to be created for the sequence, and Schofield admitted that the way and order he assigned tasks stopped the sequence working properly. To make the sequence work, the team shifted a "layered" production structure which focused on finishing one section at a time, so they could pinpoint any problems with ease. The team had to cut two other unspecified pieces to allow the tentacle sequence to work. Ultimately this problem helped build up team confidence, allowing them to tackle other problems in the game and add more content.[22]

The character animation was designed to be realistic, with extensive transitional animations to smooth out shifts between different stances for both the player, other characters and enemies.[34] The zero-G sections were in place alongside the setting, and the team performed extensive research on real space exploration and survival to get the atmosphere and movement right.[35] Implementing zero-G was difficult for the team, with Beaver describing the process as "months and months and months of work". While technically easy to achieve by switching off gravity values in Havok, reprogramming sections to be convincing and fun to play presented different challenges.[25] Isaac needed a separate series of animations for zero-G environments, with his sluggish movement achieved by animation director Chris Stone doing an exaggerated stomping walk with bungee cables strapped to his legs.[34] Due to the number of ways Isaac could die, his model was given dozens of points where he could be torn apart, and the death scenes became a part of the game's visual identity.[22] A key issue for the team when designing the horror elements was not reusing the same scares too many times, and allowing for moments of safety for the player without completely losing the tension.[36] In earlier builds, the team made extensive use of jump scares, but as they grew less frightening they were thinned out, and more emphasis was placed on the in-game atmosphere.[33]

Scenario and art design

When the game was titled Rancid Moon, Schofield envisioned a scenario similar to Escape from New York set on a prison planet in outer space. The team liked the "space" element, but disliked the prison setting.[20] Contrasting with many game productions at the time where the story had a low priority, the team chose to have the story defined from the outset, then build the levels and objectives around it. The first solid concept was the mining of planets by humans, with the twist that one planet they mine holds something dangerous.[38] Due to the focus on player immersion, there were little to no traditional cutscenes, with all the narrative being communicated through real-time interaction.[38][39] The world's themes of religion and rogue states outside Earth's control were decided upon to ground the science fiction narrative.[13] Unitology emerged five months into development as Schofield felt something was missing. After reading up on the Chicxulub crater, Scholfield wrote the original Marker as the object which caused the crater, and built Unitology around it.[40]

A key early inspiration for the game's tone was the film Event Horizon.[14][22] Schofield cited the film's use of visual storytelling and camera work, referencing a particular scene where the audience sees a scene of gore missed by the on-screen character, as an early inspiration.[22] Another strong influence on Schofield was the French horror film Martyrs.[40] Several elements made reference to other science fiction movies; Isaac's struggle was compared to that of Ellen Ripley from Alien, the dementia suffered by characters referenced Solaris, and the sense of desperation mirrored that in the story of Sunshine.[14] How the story was conveyed was a mechanical challenge due to both the real-time elements and the ability to complete some objectives out of order.[30]

The scenario was a collaborative effort between Warren Ellis, Rick Remender and Antony Johnston.[37] Ellis created a lot of the background lore and groundwork.[41] This draft was given to Remender, who wrote out planned scenes, added some scenes of his own, and performed rewrites before the script was handed to Johnston.[37] Johnston, who was involved in writing the game's additional media, worked references to those other works into the game's script. While the scripting process lasted two years, Johnston only worked on the game for the last eight months of that time. Much of his work focused on the dialogue, which had to fit around key events which had already been solidified. Johnston also contributed heavily to the audio logs, which he used to create additional storyline and flesh out the narrative.[42]

Isaac, with his non-military role and backstory, was meant to appeal to players as an average person who was not trained for combat or survival.[19] His armour and weapon design followed the principle of him being an untrained engineer; the armour is a work suit for conditions compared by staff to an oil rig in space, while the weapons are mining tools.[13][29] Isaac's name made reference to two science fiction authors, Isaac Azimov and Arthur C. Clarke.[27] The design of the ship environments deliberately moved away from traditional science fiction, which they saw as being overly clean and lacking function.[23] The large number of familiar environments and designs, in addition to making the Ishimura a believable living environment, increased the horror elements as they would be familiar to players.[43] To achieve the realistic feel, they emulated Gothic architecture, which fitted their vision both practically and aesthetically.[23] The lighting was based on light from the strong lamps used in dentistry.[43]

The Necromorphs were designed by Wanat. Similar to the ship design, Wanat designed the Necromorphs to be realistic and relatable.[23] His approach to them was to illustrate how the human form looked after it was "ravaged by a violent transformation that literally ripped it inside out". They retained elements of their original human form, increasing their disturbing nature.[30] As reference, the team used medical images and scenes from car crashes, copying injuries and incorporating them into the monster designs.[44][30] Those images were also used as reference for the dead bodies scattered round the environment.[44] The Necromorphs' multi-limbed or tentacled appearance was dictated by the dismemberment gameplay, as having enemies without limbs would not work in that context.[32] Their in-universe naming drew inspiration from the kind of code naming that happens in war zones among soldiers.[43]

Audio

Sound design

Schofield insisted from an early stage that emphasis be placed on the music and audio design to promote the horror atmosphere.[22] The sound work was led by Don Veca, and the team included Andrew Lackey, Dave Feise and Dave Swenson. Each member's work often overlapped with others.[45] Feise, the first member to join, mostly worked on weapon designs and the "tweaky futuristic synth" elements. Swenson was described as a jack of all trades, working on a wide array of elements and in particular creating impact sounds and handling the more scripted linear sections.[46] Lackey's contributions focused on boss fights and the opening sections.[45] Despite Veca's executive role, he "stayed in the trenches" as much as possible and worked on every aspect of the sound design.[46] For one of the areas in the game, which had no enemies but relied on sound and lighting, audio director Don Veca used sounds recorded from a Bay Area Rapid Transit train; the results were described by Schofield as a "horrible sound". The monster noises used a base of human noises; as an example, the small Lurker enemies used human baby sounds as a base mixed in other noises such as panther growls.[47]

As with other elements of production, the team wanted to emphasise realism. When it came to zero-G environments, they muted and muffled any sound and focused on noises from within Isaac's suit, as these mirrored actual experiences in a space vacuum.[47] The sounds played into gameplay, as the team wanted players to use sound cues to help anticipate enemy attacks while also stoking their fear.[45] The team wanted to recreate the scripted sound design of linear horror films in an interactive environment. They watched their favorite horror films, noting their use of sound effects and music, and implementing them into Dead Space.[48] One of the constant issues was optimising the limited amount of RAM the team had for both music and sound effects, which partly inspired the development of specific tools rather than using popular sound design systems.[46]

The dialogue and voice implementation was handled by Andrea Plastas and Jason Heffel.[46] The voice audio was recorded during motion capture sessions with the actors.[46] The cast included Tonantzin Carmelo as Kendra, Peter Mensah as Hammond, and Keith Szarabajka as Kyne.[49][50] Isaac is a masked silent protagonist, so the team worked to incorporate personality into his appearance and movements, with a large number of animations for his various conditions and actions. This approach was based on the portrayal of Gordon Freeman in Half-Life 2.[22][27] A vetoed suggestion from Electronic Arts in early production was that a famous actor should portray Isaac.[27]

To control the sound design elements, the team created custom software tools.[46] One of the tools they created was dubbed "Fear Emitters", which controlled the volume of music and sound effects based on distance from threats or key events.[47] Other sound tools included "Creepy Ambi Patch", which acted as a multitrack organiser for the various sound layers and added randomised internal sounds to create a greater sense of dread; "Visual Effects", which incorporated sound effects naturally into the environment and to specific areas; and "Deadscript", a scripting language developed as a replacement for a sound language later used for Spore that was taking up too much space in the game's code.[46]

Music

The music for Dead Space was composed by Jason Graves. He had a background in classical music and composition for film and television before debuting in video games through his work on King Arthur.[51][52] When Veca spoke about their intention for the score, he described their wished-for music as dark and "Aleatoric in style", ranging from eerie sounds to loud cacophonous sections.[53] Graves joined the project during early production, when the game was a quarter of the way through development.[54] He received the job after hearing from his agent that Electronic Arts was looking for a composer who could create an unconventional sound.[51] During their requests for composers, the team cited the work of Christopher Young as a reference for applicants. A later direct inspiration was the score for The Shining.[54] Using the available guidelines, Graves put together a sample demo, which both got him the job and greatly impressed Veca.[52]

When Graves got the job, he was told that the team wanted "the scariest music anyone had ever heard". As part of his research, Grave listened to a lot of modern experimental orchestral music.[52] Graves and Veca shared a common music source so they both understood the end goal.[51] Rather than creating character themes and bombastic pieces, Graves created a score based on moody ambience. The few setpiece tracks were composed for boss encounters or scripted chase sequences.[54] He based the musical style on the name Necromorph itself, with "Necro" meaning "death" and "morph" meaning "to change"; he wanted to make a musical version of that concept.[55] His being on the project from such an early stage greatly influenced the style and pacing of the music. He was regularly sent movies of level playthroughs as reference for his work. The entire score was recorded using a live orchestra, but Graves recorded each section separately so the elements could be adjusted based on the in-game situation.[54] Many of the ambient elements were created by Graves having recordings for string or brass sections allowed to each play any note they wanted, then he would take the resultant sounds and mix them.[52] One of the samples played during the game's credits came from the sample demo which won Graves the job.[54]

The music recording sessions took place at the studio of Skywalker Sound.[51] The music had four different interactive layers prepared, interacting depending on the in-game situation. This element made Graves nervous, as both the sound he was creating and how it was being integrated had not been done before in gaming.[56] At one point, he was afraid that half their recording budget would be spent on elements that could be scrapped as unworkable.[55] The game credited both Graves and Rod Abernethy as composers, but Veca clarified that while Abernethy was involved early on, all the music was composed by Graves.[46] According to Graves, Abernethy helped with the project logistics and was present during the early brainstorming sessions.[51] The final in-game score for Dead Space was three hours long and recorded over five months, several times more than Graves had composed for previous video game titles.[54] Graves described it as the most challenging and enjoyable composing job he had undertaken for a game, praising the amount of freedom he was given by the sound team.[53]

Release

Dead Space was announced in September 2007.[57] Dead Space formed part of a strategy formed under Electronic Arts's new management to push new original intellectual properties over their previous licensed and sports properties.[58][59] The website went live in March 2008, featuring screenshots from the game, an animated trailer, a developer blog, and a dedicated forum.[60] The game received a large amount of marketing support from Electronic Arts.[59] Initially, Dead Space Community Manager Andrew Green stated that Germany, China and Japan banned the game. However, it was confirmed that this was a marketing ploy and that Dead Space was not banned in any country.[61]

In North America, the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 versions of Dead Space released on October 13, 2008, with the PC version releasing on October 20. All versions released in Australia on October 23, and in Europe on October 24.[62] The PC version was one of the Electronic Arts releases protected by the controversial digital rights management product SecuROM.[63] Electronic Arts released an Ultra Limited Edition of the game limited to 1,000 copies. The package includes the game, Dead Space: Downfall, a bonus content DVD, the Dead Space art book, a lithograph and the Dead Space comic.[64] The people who bought the game within the first two weeks of its release could download the exclusive suits for free: the Obsidian Suit for the PlayStation 3 version and the Elite Suit for the Xbox 360 version.[65] After release, additional gameplay perks in the form of suits and weapons were released as paid downloadable content.[66]

Related media

Alongside the video game, the Dead Space team and Electronic Arts created a multimedia universe around the game to both promote it and show off different elements of its lore and story referenced in the game.[67] This positive response and development was prompted by enthusiasm for the vertical slice demo.[13] The first media expansion was a limited comic series written by Johnston and illustrated by Ben Templesmith, running between March and September 2008.[68][69] The next was an animated film, Dead Space: Downfall, produced by Film Roman and released in October 2008.[70][71] The comic covers the five weeks following the Marker's discovery on Aegis VII,[72] while Downfall reveals how the Ishimura was overtaken.[70]

In addition, Electronic Arts launched an episodic alternate reality game with a dedicated website titled No Known Survivors.[73] No Known Survivors was developed by web creator Deep Focus.[74][75] The challenge for Deep Focus was creating an immersive experience which would excite potential players, while being unique to the online environment. According to Creative Director Nick Braccia, the aim was to take pieces of the Dead Space lore and "blow [them] up" in ways that could only work in this environment. While more interactive events were considered, the production timeline meant several concepts were cut. The point and click interface style, and the limited exploration space of a single room per scenario, was chosen due to technical limitations and to create an experience impractical on mainstream consoles.[74] The scenario of No Known Survivors was written by Johnston.[42]

Unlocked over the nine weeks prior to the game's release, players opened the different episodes using graphics of mutated human limbs. Exploring in the style of a point and click adventure game, the story was split across two episodic stories, told through a combination of audio logs, short animations and written documents found in each environment.[73][74] The two episodes were "Misplaced Affection", which told of a hiding medical technician remembering his attempted affair with another crewperson; and "13", which focused on a government sleeper agent planted aboard the Ishimura.[73][74] It began its release on August 25.[73] The final episode of content was released on October 21, alongside the game.[76] Signing up on particular dates unlocked a discount for the game, with the top prize being a reproduction of Isaac's helmet.[77]

Reception

Critical reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On review aggregate website Metacritic, the 360 version scored 89 out of 100 based on 79 reviews.[78] The PS3 version scored 88 out of 100 based on 67 reviews,[79] while the PC version scored 86 out of 100 based on 28 reviews.[80] All scores denoted "generally favorable reviews" from critics.[78][79][80]

Upon release, Dead Space earned critical acclaim from many journalists.[67] Matt Leone of 1Up.com praised its innovations in third-person gameplay, though faulted several elements that felt like padding.[81] Computer and Video Games's Matthew Pellett was similarly positive about the gameplay and lore, though wishing for more zero-G sections and again faulting its length.[82] Dan Whitehead, writing for Eurogamer, enjoyed the experience despite some frustrating design elements and other parts that clashed with the horror aesthetic.[83] Andrew Reiner of Game Informer enjoyed his time with the game, praising its committent to horror elements and gameplay elements. In a second opinion, Joe Juba called it "the premiere accomplishment in survival horror since Resident Evil 4".[84] GamePro gave the game a perfect score, praising almost every aspect of the experience except for a lack of additional gameplay modes.[85]

Lark Anderson of GameSpot praised the enemy design and behavior, praising it as being able to stand out within the survival horror genre.[86] GameTrailers was positive about the game's use of both many horror tropes and its references to other horror and science fiction properties, saying players would be compelled to push on despite the disturbing atmosphere.[87] IGN's Jeff Haynes faulted some overpowered mechanics and frustrating New Game+ elements, but generally praised it as an enjoyable new title in the genre.[11] Meghan Watt, writing for Official Xbox Magazine, was less positive due to several mechanical frustrations and a lack of scary elements.[88] Jeremy Jastrzab of PALGN summed the game up as "easily the most atmospherically intense, genuinely scary and well-built survival horror experience of this current generation".[89]

The storyline saw a mixed reaction; many praised its atmosphere and presentation,[11][82][85] but other critics found it derivative or poorly written.[83][84][88] Where mentioned, the graphics and environmental design were praised.[11][81][86][89] The voice acting and sound design were also well received, with the latter being praised for reinforcing the horror atmosphere.[11][84][87] The twist on combat mechanics and enemy behavior design met with much praise,[11][83][84][86][88][89] but repetitive level and mission structure were often faulted.[81][86][88][89] The complete lack of a HUD was also positive noted.[11][83][84]

Several retrospective journalistic and website articles have ranked Dead Space as one of the greatest video games of all time, pointing out its innovations in the survival horror genre.[90][91][92][93][94][95] A 2011 GamePro article noted that the game promoted Electronic Arts as a potential home for original IPs, and generally found a balance between action and horror despite some contemporary reviews having mixed reactions.[67] In an article on the series from 2018, Game Informer said the title stood out for its unique gameplay gimicks and atmosphere compared to other video games of the time.[13] Magazine Play, in a 2015 feature on the game's production, said that Dead Space distinguished itself by incorporating more action elements into established genre elements, and positively compared its atmosphere to BioShock from 2007 and Metro: Last Light from 2013.[23] In a 2014 article concerning the series' later developments, Kotaku cited it as "one of the best horror games of the seventh generation of consoles".[96]

Sales

At release, Dead Space reached tenth place in North American game sales, compiled in November by the NPD Group. Recording sales of 193,000 units, it was the only new property to enter the top ten.[97] It was the only Electronic Arts property within that group.[98] In early analysis, low sales of the title were attributed to strong market competition at the time, though sales improved over time due to positive critical reception.[99] By December, the game had sold 421,000 units across all platforms. The game, along with Mirror's Edge, was considered a commercial disappointment following its extensive marketing. Electronic Arts CEO John Riccitiello said that the company would have to lower its expected income for the fiscal year due to multiple commercial disappointments including Dead Space.[59] In February 2009, Electronic Arts CFO Eric Brown confirmed that all versions of Dead Space had sold one million copies worldwide.[100]

Awards

| Year | Award | Category | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | NAVGTR | Camera Direction in a Game Engine | Nominated | [101] |

| Animation in a Game Cinema | Won | |||

| Art Direction in a Game Cinema | Nominated | |||

| Camera Direction in a Game Engine | Won | |||

| Direction in a Game Cinema | Nominated | |||

| Lighting/Texturing | Won | |||

| Sound Editing in a Game Cinema | Won | |||

| Sound Effects | Won | |||

| Use of Sound | Won | |||

| Game Original Action | Nominated | |||

| Game Developers Choice Awards | Audio | Won | [102] | |

| 2009 | ||||

| 5th British Academy Games Awards | Action & Adventure | Nominated | [103] | |

| Artistic Achivement | Nominated | |||

| Original Score | Won | |||

| D.I.C.E. Awards | Outstanding Achievement in Sound Design | Won | [104] | |

| Action Game of the Year | Won | |||

| Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction | Nominated | |||

| Outstanding Achievement in Original Music Composition | Won | |||

| Annie Awards | Best Animated Video Game | Nominated | [105] | |

| Spike Video Game Awards 2008 | Best Action Adventure Game | Nominated | [106] | |

| Game Audio Network Guild Awards | Audio of the Year | Won | [107][108] | |

| Music of the Year | Nominated | |||

| Sound Design of the Year | Won | |||

| Best Use of Multi-Channel Surround in a Game | Nominated | |||

Sequels

Following the success of Dead Space, EA Redwood Shores was restructured as a "genre studio" called Viceral Games, going on to develop several titles alongside their work on the Dead Space franchise, which spawned both further additional media and spin-off titles on several platforms.[109][110] A direct sequel, Dead Space 2, was released in 2011.[110][111] A third title, Dead Space 3, released in March 2013.[112] The third game met with disappointing sales,[113] and a prospective sequel was cancelled before Visceral Games was closed down in 2017.[110][114]

References

- Wales, Matt. "Dead Space Preview". IGN. Archived from the original on February 10, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- Haynes, Jeff (May 17, 2008). "Dead Space Hands-on". IGN. Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- Gamer 2008, p. 19-20.

- Gamer 2008, p. 16.

- Gamer 2008, p. 22-23.

- Graziani, Gabe (October 9, 2007). "Previews: Dead Space". GameSpy. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- Prima 2008, p. 5-11.

- Haynes, Jeff (September 5, 2008). "Weapons of Dead Space". IGN. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- Gamer 2008, p. 24.

- Haynes, Jeff (July 17, 2008). "E3 2008: Dead Space Upgrade Preview". IGN. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "Dead Space Review". IGN. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- Prima 2008, p. 144.

- Hillard, Kyle (November 22, 2018). "Dead Space – Reliving Isaac Clarke's Horrifying Inaugural Journey 10 years Later". Game Informer. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Ahearn, Nate (July 29, 2008). "Dead Space: Cracking Planets". IGN. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Reeves, ben (December 8, 2009). "Staring Into The Void: The Lore of Dead Space". Game Informer. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Taljonick, Ryan (January 31, 2013). "Dead Space 3 - Must-know facts about the Dead Space universe". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Prima 2008, p. 4.

- Prima 2008, p. 12-13.

- Electronic Arts, G4tv (December 9, 2009). Dead Space: Isaac Clarke Featurette (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Electronic Arts (March 10, 2008). Dead Space Dev Diary #1 - Getting to Greenlight (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Wright, Steve (October 3, 2014). "Interview: Sledgehammer's Michael Condrey on Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare". Stevivor. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Ars Technica (January 8, 2019). How Dead Space's Scariest Scene Almost Killed the Game / War Stories / Ars Technica (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Peppiatt, Dom (2015). "The Making Of... Dead Space". Play. Imagine Publishing (256): 76–79.

- Sinclair, Brendan (March 27, 2009). "GDC 2009: Reliving Dead Space". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Gamer 2008, p. 27-29.

- Onder, Clan (March 30, 2020). "Interview: Glen Schofield talks Striking Distance, new PUBG game, and more". GameZone. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Kolan, Patrick (September 11, 2008). "Dead Space AU Interview". IGN. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- "How Resident Evil 4 turned System Shock 3 into Dead Space". PC Gamer. January 15, 2017. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- Gama 2008, p. 2.

- Cheer, Dan (October 1, 2008). "Dead Space Q&A". GamePlanet. Archived from the original on October 20, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Gama 2008, p. 3.

- Electronic Arts (July 7, 2008). Dead Space Dev Diary #4: Strategic Dismemberment (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Kelly, Neon (September 22, 2009). "Dead Space Interview". VideoGamer.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Electronic Arts (September 26, 2008). Dead Space Dev Diary #7 - Animation (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Electronic Arts (September 9, 2008). Dead Space Dev Diary #6: Zero G (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Electronic Arts (August 4, 2008). Dead Space Dev Diary #5: Creating Horror (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Biessener, Adam (April 19, 2010). "Inside Bulletstorm Writer Rick Remender's Head". Game Informer. Archived from the original on April 22, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Electronic Arts (May 8, 2008). Dead Space Dev Diary #2 - Developing the Story (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Gama 2008, p. 1.

- Hutchinson, lee (January 8, 2019). "Video: Dead Space's scariest moment almost dragged down the entire project". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Snow, Jean (August 8, 2008). "Warren Ellis Gives "Dead Space" Its Creepy Narrative". Wired. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Fitch, Alex (June 23, 2009). "Antony Johnston interview". Sci-fi-London. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Electronic Arts (October 13, 2008). Dead Space Dev Diary #8 - Art and Necromorphs (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Schofield, Glen (October 14, 2008). "Glen Schofield Writes for Edge". Edge. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Isaza, Miguel (December 16, 2009). "Andrew Lackey Special: Dead Space [Exclusive Interview]". Wasabi Sound. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Napolitano, Jayson (October 7, 2008). "Dead Space Sound Design: In Space No One Can Hear Interns Scream. They Are Dead". Original Sound Version. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Electronic Arts (June 19, 2008). Dead Space Dev Diary #3 -- Audio (Web video). YouTube (Video). Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Veca, Don (November 28, 2008). "The Music of Dead Space: Artistic Design and Technical Implementation". Music4Games. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Peters, Pamela J. (September 11, 2018). "Getting to Know Los Angeles Tongva Actress - Tonantzin Carmelo". Native News Online. Archived from the original on December 13, 2018. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- "Behind the Voice Actors - Dead Space". Behind the Voice Actors. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- "Interview with Jason Graves - Dead Space soundtrack composer". Game-OST. 2008. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Gonzalez, Annette (January 23, 2011). "Dead Space Composer Jason Graves Explains The Unsettling Score". Game Informer. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- "Dead Space Reveals Spine-Tingling Score Composed and Conducted by Jason Graves". Music4Games. June 10, 2008. Archived from the original on June 26, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- "Dead Space Composer Interview". IGN. October 18, 2008. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Thurmond, Joey (May 16, 2015). "Interview: The Man Behind the Music - Jason Graves". Push Square. Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Cowen, Nick (January 17, 2011). "Dead Space 2: Jason Graves interview". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Jenner, Laura (September 24, 2007). "EA ventures into Dead Space". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 27, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Fahey, Rob (March 6, 2008). "Electronic Arts: Back In The Game". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- "In Depth: Inside Mirror's Edge, Dead Space Sales Weakness". Gamasutra. December 17, 2008. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Burg, Dustin (March 5, 2008). "Official Dead Space website is alive". Engadget. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Plunkett, Luke (December 17, 2008). "So Dead Space Was Banned, Well, Nowhere — Dead Space". Kotaku. Archived from the original on March 19, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- "EA Announces That Dead Space Has Gone Gold". September 4, 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- Welsh, Ollie (April 1, 2009). "EA allows SecuROM de-authorisation". GamesIndustry.bi. Archived from the original on April 3, 2009. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Ben Swanson: The Ultra Limited Edition is Here!". September 26, 2008. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- "Kotaku: Dead Space Gold, Platform Exclusive Suits For Launch Players". Kotaku. October 1, 2008. Archived from the original on October 3, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- Garrett, Patrick (November 10, 2008). "Dead Space DLC packs detailed and dated". VG247. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- Seppala, Timothy J. (January 24, 2011). "Dead Space retrospective". GamePro. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- "EA and Image Comics Announce Dead Space Comic Series With Ben Templesmith and Antony Johnston". Electronic Arts. February 21, 2008. Archived from the original on May 9, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Image Comics Schedule - In Stores the week of September 17, 2008". Image Comics. Archived from the original on September 12, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Gamer 2008, p. 18.

- Monfette, Christopher (August 22, 2008). "Dead Space Details Emerge". IGN. Archived from the original on May 16, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- George, Richard (March 6, 2008). "Dead Space #1 Review". IGN. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Dead Space Expanded". IGN. August 25, 2008. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Reilly, Jim (September 27, 2008). "No Known Survivors Takes Dead Space's Narrative To The Web". Kotaku. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Rose, Frank (March 13, 2012). The Art of Immersion: How the Digital Generation is Remaking Hollywood, Madison Avenue, and the Way We Tell Stories. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 80.

- Hart, Hugh (October 21, 2008). "Dead Space Launches Webisode Finale". Wired. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Cavalli, Earnest (October 6, 2008). "Exclusive Assets From EA's Eerie Dead Space Add". Wired. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- "Dead Space (Xbox 360)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- "Dead Space (PlayStation 3)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- "Dead Space (PC)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- Leone, Matt (October 13, 2008). "Dead Space Review". 1Up.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- Pellett, Matthew. "Review: Dead Space". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on March 27, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- Whitehead, Dan (October 13, 2008). "Dead Space Review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- Reiner, Andrew. "Dead Space Review". Game Informer. Archived from the original on June 10, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- Moses, Travis (October 11, 2008). "Review: Dead Space (360)". GamePro. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- "Dead Space for Xbox 360 Review". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. October 13, 2011. Archived from the original on June 18, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- "Review: Dead Space". GameTrailers. October 21, 2008. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- "Dead Space Review". Official Xbox Magazine. Archived from the original on March 14, 2009. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- Jastrzab, Jeremy (November 7, 2008). "Dead Space Review". PALGN. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- "The Top 300 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 300. April 2018.

- "Edge Presents: The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Edge. August 2017.

- "All-TIME 100 Video Games". Time. November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". slantmagazine.com. June 9, 2014. Archived from the original on July 12, 2015.

- "The 100 Best Games of All-Time". GamesRadar. February 25, 2015. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- Polygon Staff (November 27, 2017). "The 500 Best Video Games of All Time". Polygon.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- Burford, G. B. (September 30, 2014). "How The Dead Space Saga Lost Its Way". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- "NPD: October sales defy market plunge". GameSpot. November 13, 2008. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Richtel, Matt (December 10, 2008). "Electronic Arts Forecasts Weaker Profit in 2009". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Graft, Kris (November 10, 2008). "Reviews Liven Up Dead Space Sales - Analyst". Edge. Archived from the original on November 12, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- "Mirror's Edge, Dead Space Break 1 Million". Shacknews. February 3, 2009. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- "NAVGTR: 2008 Awards". NAVGTR. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "9th Annual Game Developers Choice Awards". Game Developers Choice Awards. 2008. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Video Games Awards Winners". British Academy Games Awards. March 10, 2009. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "Dead Space". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on June 5, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- McWhertor, Michael (February 3, 2009). "Kung Fu Panda Had The Best Video Game Animation Of 2008. Conversation Over". Kotaku. Archived from the original on October 19, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Kietzmann, Ludwig (November 13, 2008). "Presenting the 2008 Spike Video Game Award nominees". Engadget. Archived from the original on May 17, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- McElroy, Griffen (February 17, 2009). "LittleBigPlanet snags eight nominations in GANG audio awards". Engadget. Archived from the original on May 18, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- "7th Annual Game Audio Network Guild (G.A.N.G.) Award Winners". Music4Games. March 30, 2009. Archived from the original on September 1, 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Nutt, Christopher (February 10, 2010). "A Distinct Vision: Nick Earl And Visceral Games". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- McCarthy, Caty (October 19, 2017). "The Rise and Fall of Visceral Games". US Gamer. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- McElroy, Griffin. "Dead Space 2 comes with Move-based Extraction on PS3". Joystiq. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- Conditt, Jessica (May 7, 2012). "Need for Speed and Dead Space titles coming by March 2013". Joystiq. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- "Dead Space 4 canned, series in trouble following poor sales of Dead Space 3". VideoGamer.com. March 4, 2013. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Makar, Connor (July 13, 2018). "Visceral had some cool ideas for Dead Space 4". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

Bibliography

- Bueno, Fernando (October 24, 2008). Dead Space Prima official Strategy Guide. Prima Games.

- "Cover Story - Dead Space". Hardcore Gamer. Imagine Publishing (Volume 4, Issue 3). September 2008.

- Remo, Chris (September 29, 2008). "A New Vocabulary For Development: Chuck Beaver And Dead Space". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.