De Mulieribus Claris

De Mulieribus Claris or De Claris Mulieribus (Latin for "Concerning Famous Women") is a collection of biographies of historical and mythological women by the Florentine author Giovanni Boccaccio, composed in 1361–62. It is notable as the first collection devoted exclusively to biographies of women in Western literature.[2] At the same time as he was writing On Famous Women, Boccaccio also compiled a collection of biographies of famous men, De Casibus Virorum Illustrium (On the Fates of Famous Men).

Purpose

BnF Français 599, fol.27v

Boccaccio claimed to have written the 106 biographies for the posterity of the women who were considered renowned, whether good or bad. He believed that recounting the deeds of certain women who may have been wicked would be offset by the exhortations to virtue by the deeds of good women. He writes in his presentation of this combination of all types of women that he hoped it would encourage virtue and curb vice.[3]

Overview

The author declares in the preface that this collection of 106 short biographies[2] (104 chapters)[4] of women is the first example in Western literature devoted solely and exclusively to women.[5] Some of the lost works of Suetonius' "illustrious people" and Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium are a mixture of women and men, where others like Petrarch's De Viris Illustribus and Jerome's De Viris Illustribus are biographies of exclusively men. Boccaccio himself even says this work was inspired[6] and modeled on Petrarch's De Viris Illustribus.[7]

Development

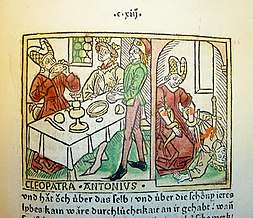

Inc B-720, fol.93

Boccaccio wrote this work in Certaldo probably between the summer of 1361 and the summer of 1362,[2] although it could have been as late as December 1362.[8] He dedicated his work to Andrea Acciaioli, Countess of Altavilla, in Naples at the end of 1362 even though he continued to revise it up until his death in 1375. She was not his first choice however. He first considered to dedicate his slim volume to Joanna I of Naples. He ultimately decided that his work as a little book was not worthy a person of such great fame.[9]

There are over 100 surviving manuscripts which shows that the De Mulieribus Claris was "among the most popular works in the last age of the manuscript book". Boccaccio worked on this as a labor of love with several versions, editions, and rearrangements in the last twenty years or so of his life: studies have identified at least nine stages in its composition.[10] In the last part of the 14th century after Boccaccio died a Donato degli Albanzani had a copy that his friend Boccaccio gave him and translated it from Latin into Italian.

Content

The 106 Famous Women biographies are of mythological and historical women, as well as some of Boccaccio's Renaissance contemporaries. The brief life stories follow the same general exemplary literature patterns used in various versions of De viris illustribus. The biography pattern starts with the name of the person, then the parents or ancestors, then their rank or social position, and last the general reason for their notoriety or fame with associated details. This is sometimes interjected with a philosophical or inspirational lesson at the end.

The only sources that Boccaccio specifically says he used are Saint Paul (no. 42), the Bible (no. 43) and Jerome (no. 86). The wording of the biographies themselves, however, provide hints about where he obtained his information. He clearly had access to works of the classical authors Valerius Maximus, Pliny, Livy, Ovid, Suetonius, Statius, Virgil, Lactantius, Orosius, and Justinus.[11]

Influence

Boccaccio's collection of female biographies inspired characters in Christine de Pizan's The Book of the City of Ladies (1405)[12] In the early part of the 15th century Antonio di S. Lupidio made a volgare translation and Laurent de Premierfait published it in French as Des cleres et nobles femmes. Boccaccio's biographies also inspired Alvaro de Luna's De las virtuosas y claras mujeres, Thomas Elyot's Defence of Good Women, Alonso of Cartagena's De las mujeres ilustres, Giovanni Sabbadino degli Arienti's Gynevera de la clare donne, Iacopo Filippo Forest's De plurimis claris selectisque mulierbus and Jean Lemaire's Couronne margaritique. In England, and various works by Edmund Spenser used Boccaccio's De Mulieribus Claris as inspiration and the famous women influenced Geoffrey Chaucer's Legend of Good Women and The Canterbury Tales(1387-1400).[13] In the beginning of the 16th century a Henry Parker translated about half into English and dedicated it to Henry VIII. In the 16th century of new Italian translations by Luca Antonio Ridolfi and Giuseppe Betussi were published.

In Germany De Mulieribus Claris was widely distributed as manuscript. The first printed book of the Latin language original was produced in the workshop of Johann Zainer and was published decorated with woodcut miniatures in 1473.[14] This 1473 edition was the first Latin version print. The only complete 16th century printed Latin version to survive is from a Mathias Apiarus done around 1539.[15] The German translation by Heinrich Steinhöwel was printed and published also by Zainer in 1474. The book became so popular that in the subsequent hundred years the Steinhöwel translation was republished in six editions. Steinhöwel had added geographic relevance, by placing the Amazons in Swabia.[16]

The famous women

- 1. Eve, the first woman in the Bible

- 2. Semiramis, queen of the Assyrians

- 3. Opis, wife of Saturn

- 4. Juno, goddess of the Kingdoms

- 5. Ceres, goddess of the harvest and queen of Sicily

- 6. Minerva

- 7. Venus, queen of Cyprus

- 8. Isis, queen and goddess of Egypt

- 9. Europa, queen of Crete

- 10. Libya, queen of Libya

- 11 and 12. Marpesia and Lampedo, queens of the Amazons

- 13. Thisbe, a Babylonian maiden

- 14. Hypermnestra, queen of the Argives and priestess of Juno

- 15. Niobe, queen of Thebes

- 16. Hypsipyle, queen of Lemnos

- 17. Medea, queen of Colchis

- 18. Arachne of Colophon

- 19 and 20. Orithyia and Antiope, queens of the Amazons

- 21. Erythraea or Heriphile, a Sibyl

- 22. Medusa, daughter of Phorcus

- 23. Iole, daughter of the king of the Aetolians

- 24. Deianira, wife of Hercules

- 25. Jocasta, queen of Thebes

- 26. Almathea or Deiphebe, a Sibyl

- 27. Nicostrata, or Carmenta, daughter of King Ionius

- 28. Procris, wife of Cephalus

- 29. Argia, wife of Polynices and daughter of King Adrastus

- 30. Manto, daughter of Tiresias

- 31. The wives of the Minyans

- 32. Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons

- 33. Polyxena, daughter of King Priam

- 34. Hecuba, queen of the Trojans

- 35. Cassandra, daughter of King Priam of Troy

- 36. Clytemnestra, queen of Mycenae

- 37. Helen, wife of King Menelaus

- 38. Circe, daughter of the Sun

- 39. Camilla, queen of the Volscians

- 40. Penelope, wife of Ulysses

- 41. Lavinia, queen of Laurentum

- 42. Dido, or Elissa, queen of Carthage

- 43. Nicaula, queen of Ethiopia

- 44. Pamphile, daughter of Platea

- 45. Rhea Ilia, a Vestal Virgin

- 46. Gaia Cyrilla (Tanaquil), wife of King Tarquinius Priscus

- 47. Sappho, woman of Lesbos and poet

- 48. Lucretia, wife of Collatinus

- 49. Tamyris, queen of Scythia

- 50. Leaena, a courtesan

- 51. Athaliah, queen of Jerusalem

- 52. Cloelia, a Roman maiden

- 53. Hippo, a Greek woman

- 54. Megullia Dotata

- 55. Veturia, a Roman matron

- 56. Thamyris, daughter of Micon

- 57. Artemisia, queen of Caria

- 58. Verginia, virgin and daughter of Virginius

- 59. Eirene, daughter of Cratinus

- 60. Leontium

- 61. Olympias, queen of Macedonia

- 62. Claudia, a Vestal Virgin

- 63. Virginia, wife of Lucius Volumnius

- 64. Flora, goddess of flowers and wife of Zephyrus

- 65. A young Roman woman

- 66. Marcia, daughter of Varro

- 67. Sulpicia, wife of Quintus Fulvius Flaccus

- 68. Harmonia, daughter of Gelon, son of Hiero II of Syracuse

- 69. Busa of Canosa di Puglia

- 70. Sophonisba, queen of Numidia

- 71. Theoxena, daughter of Prince Herodicus

- 72. Berenice, queen of Cappadocia

- 73. The Wife of Orgiagon the Galatian

- 74. Tertia Aemilia, wife of the elder Africanus

- 75. Dripetrua, queen of Laodice

- 76. Sempronia, daughter of Gracchus

- 77. Claudia Quinta, a Roman woman

- 78. Hypsicratea, Queen of Pontus

- 79. Sempronia, a Roman Woman

- 80. The Wives of the Cimbrians

- 81. Julia, daughter of the dictator Julius Caesar

- 82. Portia, daughter of Cato Uticensis

- 83. Curia, wife of Quintus Lucretius

- 84. Hortensia, daughter of Quintus Hortensius

- 85. Sulpicia, wife of Cruscellio

- 86. Cornificia, a poet

- 87. Mariamme, queen of Judaea

- 88. Cleopatra, queen of Egypt

- 89. Antonia, daughter of Antony

- 90. Agrippina, wife of Germanicus

- 91. Paulina, a Roman woman

- 92. Agrippina, mother of the Emperor Nero

- 93. Epicharis, a freedwoman

- 94. Pompeia Paulina, wife of Seneca

- 95. Poppaea Sabina, wife of Nero

- 96. Triaria, wife of Lucius Vitellius

- 97. Proba, wife of Adelphus

- 98. Faustina Augusta

- 99. Symiamira, woman of Emesa

- 100. Zenobia, queen of Palmyra

- 101. Joan, an Englishwoman and Pope

- 102. Irene, Empress of Constantinople

- 103. Gualdrada, a Florentine maiden

- 104. Constance, Empress of Rome and queen of Sicily

- 105. Camiola, a Sienese widow

- 106. Joanna, queen of Jerusalem and Sicily

References

Citations

- Royal 16 G V fol. 3v

- Boccaccio (2003), p. xi

- Boccaccio (2003), p. xii

- Boccaccio (2003), pp. xi, xxii. Biographies 11–12 and 19–20 are combined to make 104 chapters, however the biographies are I (1) through CVI (106).

- Boccaccio (2003), pp. xi, xxxvii

- Boccaccio (2003), p. 4

- Boccaccio (2003), pp. xii, xv

- Boccaccio (2003), p. 256

- Boccaccio (2003), p. xiii

- Boccaccio (2003), p. xv

- Boccaccio (2003), p. xvi

- Boitani (1976)

- Boitani (1976)

- Helen Watanabe-O'Kelly (2010). Beauty Or Beast?: The Woman Warrior in the German Imagination from the Renaissance to the Present. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780199558230.

- Boccaccio (2003), p. xx

- Helen Watanabe-O'Kelly (2010). Beauty Or Beast?: The Woman Warrior in the German Imagination from the Renaissance to the Present. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 9780199558230.

- Anderson (2003), p. 50.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Jaynie (2003), Tiepolo's Cleopatra, Melbourne: Macmillan, ISBN 9781876832445.

- Boccaccio, Giovanni (2003). Famous Women. I Tatti Renaissance Library. 1. Translated by Virginia Brown. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01130-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boitani, Piero (1976). "The Monk's Tale: Dante and Boccaccio". Medium Ævum. 45: 50–69.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

Primary sources

- Boccaccio, Poeet Ende Philosophe, Bescrivende van den Doorluchtighen, Glorioesten ende Edelsten Vrouwen (Antwerp, 1525)

- Boccaccio, Tractado de John Bocacio, de las Claras, Excellentes y Mas Famosas y Senaladas Damas (Zaragoza, 1494)

- Boccaccio, De la Louenge et Vertu des Nobles et Cleres Dames (Paris, 1493)

- Boccaccio, De Preclaris Mulieribus (Strassburg, 1475)

- Boccaccio, De Preclaris Mulieribus (Louvain, 1487)

- Boccaccio, De Mulieribus Claris (Bern, 1539)

- Boccaccio, De Mulieribus Claris (Ulm, 1473)

- Boccaccio, French translation (Paris, 1405)

Secondary sources

- Schleich, G. ed., Die mittelenglische Umdichtung von Boccaccio De claris mulieribus, nebst der latinischen Vorlage, Palaestra (Leipzig, 1924)

- Wright, H.G., ed., Translated from Boccaccio's De Claris Mulieribus, Early English Text Society, Original series w/Latin (London, 1943)

- Guarino, G. A., Boccaccio, Concerning Famous Women (New Brunswick, N.J., 1963)

- Zaccaria, V., ed., De mulieribus claris with Italian translation (Milan, 1967 and 1970)

- Branca, V., ed., Tutte le opere di Giovani Boccaccio, volume 10 (1967) Questia

- Zaccaria, V., ed., De mulieribus claris, Studi sul Boccaccio (Milan, 1963)

- Kolsky, S. , Ghost of Boccaccio: Writings on Famous Women, (2005)

- Franklin, M., Boccaccio's Heroines: Power and Virtue in Renaissance Society (2006)

- Filosa, E., Tre Studi sul De mulieribus claris (2012)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to De mulieribus claris. |