Sophonisba

Sophonisba ( in Punic, 𐤑𐤐𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋 Ṣap̄anbaʿal) (fl. 203 BC) was a Carthaginian noblewoman who lived during the Second Punic War, and the daughter of Hasdrubal Gisco. She held influence over the Numidian political landscape, convincing king Syphax to change sides during the war, and later, in an act that became legendary, she poisoned herself rather than be humiliated in a Roman triumph.

- For the Renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532–1625), see Sofonisba Anguissola. For the American activist Sophonisba Breckinridge (1866–1948), see Sophonisba Breckinridge.

Name

The form of the name Sophonisba is not known until the fifteenth century, in a few late manuscripts of Livy, but it is the better known form because of later literature. She's also called Sophonisbe and Sophoniba. However, her true name might be unclear. Her story is told in Livy (30.12.11-15.11), Diodorus (27.7), Appian (Pun. 27-28), and Cassius Dio (Zonaras 9.11), but Polybius, who had met Masinissa, never refers to Sophonisba by name in his allusions to her (14.4ff.). Nevertheless, it has been proposed that Polybius' account provides the basis for the Sophonisba story.[1]

Biography

In 206, Sophonisba had been betrothed to the King Masinissa, a leader of the Massylii or eastern Numidians who served along with Gisco against Rome in Hispania, in order to conclude the diplomatic alliance between Carthage and the Massylii. However, the Carthaginian Senate prohibited the wedding and ordered Sophonisba to marry Syphax, chieftain of the western Masaesyli, who up to that point had been allied to Rome. Cassius Dio suggests that this was because Syphax was considered a better ally, while Appian tells Syphax was in love with Sophonisba and actively pressed for the marriage, harassing Carthage with revolts and threatening attacks alongside Roman forces until they conceded. In any case, Sophonisba married Syphax in 206, turning him into Carthage's greatest ally in African terrain. Meanwhile Masinissa, disgruntled by the circumstances, secretly allied himself with Scipio Africanus and returned to his lands.[2] Some believe those accounts might be embellished, as Livy implies Masinissa met her for the first time after the Battle of Cirta, but this is not entirely incompatible with the previous.[3]

Classical chroniclers praise Sophonisba for her virtues and skill. Diodorus Siculus called her "comely in appearance, a woman of many varied moods, and one gifted with the ability to bind men to her service,"[4] while Cassius Dio states she had a high education in music and literature and was "clever, ingratiating, and altogether so charming that the mere sight of her or even the sound of her voice sufficed to vanquish every one, even the most indifferent."[5] Polybius also emphasizes her youth, calling her a "child" bride, something which Diodorus also mentions. Nevertheless, those traits have led to modern historians to consider her a true political agent for Carthage instead of a mere pawn of the war.[6]

Loyal to her city, Sophonisba managed to make Syphax join forces with Hasdrubal and face Scipio and Masinissa in the Battle of the Great Plains on the Bagradas, but the Punic force ended up ultimately defeated. Syphax was then defeated and captured in 203 BC in the Battle of Cirta. When Sophonisba fell in Masinisa's hands, he freed her and married her, accepting that she had been forced to marry Syphax against her will. However, after hearing claims (confirmed by Gaius Laelius's inquiries)[7] that Syphax had acted against Rome under the influence of Sophonisba, Scipio refused to agree to this arrangement, fearing she would turn Masinissa against him as well. He insisted on the immediate surrender of the princess so that she could be taken to Rome and appear in the triumphal parade.[8] On the other hand, Plutarch considers Scipio asked for Sophonisba's delivery for safety reasons, fearing Masinissa could torment her in revenge for her marriage to Syphax.[9]

Although Masinissa loved Sophonisba, he accepted to leave her before being declared an enemy to Rome, and went to Sophonisba. He told her that he could not free her from captivity or shield her from Roman wrath, and so he asked her to die like a true Carthaginian princess. With great composure, she drank a cup of poison that he offered her and died, berating Masinissa for making their marriage short and bitter. Afterwards, Masinissa handed Scipio her corpse. His kingdom and Rome remained allied for long after Masinissa's death in 148 BC.

In literature, art and film

Petrarch elaborated her story in his epic poem Africa, published posthumously in 1396.

The playwright John Marston wrote The Wonder of Women, a Roman tragedy based on the story of Sophonisba, in 1606 for the Children of the Queen's Revels.

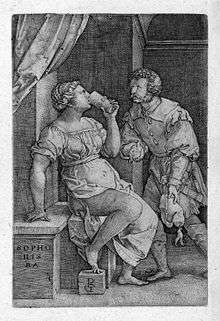

There are a number of paintings of Sophonisba drinking her poison, but the subject is often very similar to that of Artemisia II of Caria drinking her husband's ashes, and the Rembrandt in the Prado and a Donato Creti in the National Gallery are examples of works where the intended subject remains uncertain between the two.[10]

Sophonisba became the subject of tragedies (and later operas) from the 16th to the 19th centuries, and, along with the story of Cleopatra, furnished more dramas than any other. The first tragedy is credited to the Italian Galeotto Del Carretto (c. 1470–1530) which was written in 1502, but issued posthumously in 1546. The first to appear, however, was Gian Giorgio Trissino's play of 1515 which, "in codifying the forms of Italian classical tragedy, helped consign Del Carretto's Sofonisba to oblivion."[11] In France, Trissino's version was adapted by Mellin de Saint-Gelais (performed in 1556), and may have served as the primary model for versions by Antoine de Montchrestien (1596) and Nicolas de Montreux (1601). The tragedy by Jean Mairet (1634) is one of the first monuments of French "classicism", and was followed by a version from Pierre Corneille (1663).

The story of Sophonisba also served as subject for works by John Marston (1606), David Murray (1610), Nathaniel Lee (1676), Daniel Caspar von Lohenstein (1680), Henry Purcell (1685), Antonio Caldara (1708), Leonardo Leo (1718), Luca Antonio Predieri (1722), James Thomson (1729), Niccolò Jommelli (1746), Baldassare Galuppi (1747, 1764), Tommaso Traetta (1762), Antonio Boroni (1764), Christopher Gluck (1765), Maria Teresa Agnesi (1765), Mattia Vento (1766), François Joseph Lagrange-Chancel, revised by Voltaire (1770), Christian Gottlob Neefe (1776), António Leal Moreira (1783), Joseph Joaquín Mazuelo (1784), Vittorio Alfieri (1789), Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi (1802), Marcos Portugal (1803), Ferdinando Paer (1805), Vincenzo Federici (1805), Luigi Petrali (1844), Emanuel Geibel (1869), Jeronim de Rada (1892), Giuseppe Brunati (1904), Dimitrie Cuclin (1945), Vasco Graça Moura (1993), and others.

Sophonisba also appears in film, first in Giovanni Pastrone's 1914 silent film Cabiria and again in Carmine Gallone's 1937 epic movie Scipio Africanus: The Defeat of Hannibal.

Gallery

Sophonisba, by Andrea Mantegna (1490)

Sophonisba, by Andrea Mantegna (1490) Sophonisba, by Georg Pencz (16th century)

Sophonisba, by Georg Pencz (16th century) Dying Sophonisba, by Guercino (1630)

Dying Sophonisba, by Guercino (1630)%2C_by_Rembrandt%2C_from_Prado_in_Google_Earth.jpg) Sophonisba Receiving the Poisoned Cup (a.k.a. Artemisia Receiving Mausolus' Ashes, by Rembrandt (1634)

Sophonisba Receiving the Poisoned Cup (a.k.a. Artemisia Receiving Mausolus' Ashes, by Rembrandt (1634) Sophonisba, by Antoni Gruszecki (1793)

Sophonisba, by Antoni Gruszecki (1793)

Notes

- Sophonisbe Archived April 5, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Appian, II, 10-11

- Butler and Scullard (1953) Livy XXX p97

- Diodorus Siculus, XXVII, 7

- Cassius Dio, H. R., XVII, 51-52.

- Carmen Soares, José Luís Brandão, Pedro C. Carvalho (2011). História Antiga: Relações Interdisciplinares. Fontes, Artes, Filosofia, Política, Religião e Receção. Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra. ISBN 978-98-926156-3-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Appian, V, 27

- Diodorus Siculus, XXVII, 7

- Plutarch, Scipio, 29

- Finaldi, Gabriele and Kitson, Michael, Discovering the Italian Baroque: the Denis Mahon Collection, p. 56, 1997, National Gallery Publications, London/Yale UP, ISBN 1857091779

- Abstract Archived 2008-08-04 at the Wayback Machine of the article “Galeotto Del Carretto’s ‘Sofonisba’” by Lovaniano Rossi, in Levia Gravia (2000). Universities of Turin and of Piemonte Orientale.

References

Livy, Ab urbe condita libri xxix.23, xxx.8, 12-15.8