Dardani

The Dardani (/ˈdɑːrdənaɪ/; Ancient Greek: Δαρδάνιοι, Δάρδανοι; Latin: Dardani) were a Paleo-Balkan tribe which lived in a region which was named Dardania after their settlement there.[1][2] The eastern parts of the region were at the Thraco-Illyrian contact zone. In archaeological research, Illyrian names are predominant in western Dardania (present-day Kosovo), while Thracian names are mostly found in eastern Dardania (present-day south-eastern Serbia). Thracian names are absent in western Dardania; some Illyrian names appear in the eastern parts. Thus, their identification as either an Illyrian or Thracian tribe has been a subject of debate; the ethnolinguistic relationship between the two groups being largely uncertain and debated itself as well.[3][4] The correspondence of Illyrian names - including those of the ruling elite - in Dardania with those of the southern Illyrians suggests a "thracianization" of parts of Dardania.[5][6] Strabo in his geographica mentions them as one of the three strongest Illyrian peoples, the other two being the Ardiaei and Autariatae.[7][8]

_DARDANIAN_KINGDOMS_EXTENT_DURING_230_BC.png)

The Kingdom of Dardania was attested since the 4th century BC in ancient sources reporting the wars the Dardanians waged against Macedon. After the Celtic invasion of the Balkans weakened the state of the Macedonians and Paeonians, the political and military role of the Dardanians began to grow in the region. They expanded their state to the area of Paeonia which definitely disappeared from history, and to some territories of the southern Illyrians. The Dardanians strongly pressured the Macedonians, using every opportunity to attack them. However the Macedonians quickly recovered and consolidated their state, and the Dardanians lost their important political role. The strengthening of the Illyrian (Ardiaean–Labeatan) state on their western borders also contributed to the restriction of Dardanian warlike actions towards their neighbors.[9]

The Dardani were the most stable and conservative ethnic element among the peoples of the central Balkans, retaining for several centuries an enduring presence in the region.[10][3]

Names

The ethnonym was spelled in Greek as Dardaneis, Dardanioi and Dardanoi, and in Latin as Dardani.[11] The term used for their territory was Dardanike (Δαρδανική),[12] while other tribal areas had more unspecified terms, such as Autariaton khora (Αὐταριατῶν χώρα), for the "land of Autariatae."

The names Dardania appears to be connected to Albanian dardhë.[13] In 1854, Johann Georg von Hahn was the first to propose that the names Dardanoi and Dardania were related to the Albanian word dardhë ("pear, pear-tree"), stemming from proto-Albanian (PAlb) *dardā, itself a derivative of derdh, "to tip out, pour", ultimately from PAlb *derda.[14][15] This is suggested by the fact that toponyms related to fruits or animals are not unknown in the region (cf. Alb. dele/delmë "sheep" supposedly related to Dalmatia, Ulcinj in Montenegro < Alb. ujk, ulk "wolf" etc.). Opinions differ whether the ultimate etymon of this word in Proto-Indo-European was *g'hord-, or *dheregh-.[16] A common Albanian toponym with the same root is Dardha, found in various parts of Albania, including Dardha in Berat, Dardha in Korça, Dardha in Librazhd, Dardha in Puka, Dardhas in Pogradec, Dardhaj in Mirdita, and Dardhës in Përmet. Dardha in Puka is recorded as Darda in a 1671 ecclesiastical report and on a 1688 map by a Venetian cartographer. Dardha is also the name of an Albanian tribe in the northern part of the District of Dibra.[17]

In ancient sources

The Dardani in the Balkans were linked by ancient Greek and Roman writers with a people of the same name who lived in northwest Anatolia (i.e. the Dardanoi), from which the name Dardanelles is derived. Other parallel ethnic names in the Balkans and Anatolia, respectively include: Eneti and Enetoi, Bryges and Phryges, Moesians and Mysians. These parallels are considered too great to be a mere coincidence. Accordin to a current explanation, the connection is likely related to the large-scale movement of peoples that occurred at the end of the Bronze Age (around 1200 BC), when the attacks of the 'Sea Peoples' afflicted some of the established powers around the eastern Mediterranean.[18] The rulers of some of the great powers of antiquity, such as Epirus, Macedonia and Rome, claimed a Trojan ancestry linking themselves to Dardanus, who according to the tradition was the founder of the Trojan ruling house. But if Dardanus and the tribes over which he ruled were descended from the Balkan people, who were considered "barbarians" by the Romans, it would have been an embarrassment. Thus, by Roman times the connection was explained by a movement that occurred in the opposite direction proposing that Dardanus caused the settling of the Dardani west of the Thracians, accepting the version that the Dardani were a people related to the Trojans, but that they had degenerated to a state of "barbarism" in their new settlement.[19]

In Greek mythology

In Greek mythology, Dardanos (Δάρδανος), one of the sons of Illyrius (the others being Enchelus, Autarieus, Maedus, Taulas, and Perrhaebus) was the eponymous ancestor of the Dardanoi (Δάρδανοι).[20]

History

4th century BC

The Dardani are first mentioned in the 4th century BC, when their king Bardylis succeeded in bringing various tribes into a single organization. Under his leadership the Dardani defeated the Macedonians and Molossians several times. At this time they were strong enough to rule Macedonia through a puppet king in 392-391 BC. In 385-384 they allied with Dionysius I of Syracuse and defeated the Molossians, killing up to 15,000 of their soldiers and ruling their territory for a short period. Their continuous invasions forced Amyntas III of Macedon to pay them a tribute in 372 BC. They returned raiding the Molossians in 360. In 359 BC Bardylis won a decisive battle against Macedonian king Perdiccas III, whom he killed himself, while 4,000 Macedonian soldiers fell, and the cities of upper Macedonia were occupied.[21][22] Following this disastrous defeat, king Philip II took control of the Macedonian throne in 358 and reaffirmed the treaty with the Dardani, marrying princess Audata, probably the daughter or niece of Bardylis. The time of this marriage is somewhat disputed while some historians maintain that the marriage happened after the defeat of Bardylis.[23] This gave Philip II valuable time to gather his forces against those Dardani who were still under Bardylis, defeating them at the Erigon Valley by killing about 7,000 of them, eliminating the Dardani menace for some time.[22][24]

In 334 BC, under the leadership of Cleitus, the son of Bardylis, the Dardani, in alliance with other Illyrian tribes attacked Macedonia held by Alexander the Great. The Dardani managed to capture some cities but were eventually defeated by Alexander's forces.[21]

3rd–1st century BC

Celts were present in Dardania in 279 BC.[25] The Dardanian king offered to help the Macedonians with 20,000 soldiers against the Celts, but this was refused by Macedonian king Ptolemy Keraunos.[26][27]

Dardani were a constant threat to the Macedonian kingdom. In 230 under Longarus[28] they captured Bylazora from the Paionians[29] and in 229 they again attacked Macedonia, defeating Demetrius II in an important battle.[30] In this period their influence on the region grew and some other Illyrian tribes deserted Teuta, joining the Dardani under Longarus and forcing Teuta to call off her expedition forces in Epirus.[31] When Philip V rose to the Macedonian throne, skirmishing with Dardani began in 220-219 BC and he managed to capture Bylazora from them in 217 BC. Skirmishes continued in 211 and in 209 when a force of Dardani under Aeropus, probably a pretender to the Macedonian throne, captured Lychnidus and looted Macedonia taking 20.000 prisoners and retreating before Philip's forces could reach them.[32]

In 201 Bato of Dardania along with Pleuratus the Illyrian and Amynander king of Athamania, cooperated with Roman consul Sulpicius in his expedition against Philip V.[33] Being always under the menace of Dardanian attacks on Macedonia, around 183 BC Philip V made an alliance with the Bastarnae and invited them to settle in Polog, the region of Dardania closest to Macedonia.[34] A joint campaign of the Bastarnae and Macedonians against the Dardanians was organized, but Philip V died and his son Perseus of Macedon withdrew his forces from the campaign. The Bastarnae crossed the Danube in huge numbers and although they didn't meet the Macedonians, they continued the campaign. Some 30,000 Bastarnae under the command of Clondicus seem to have defeated the Dardani.[35] In 179 BC, the Bastarnae conquered the Dardani, who later in 174 pushed them out, in a war which proved catastrophic, with a few years later, in 170 BC, the Macedonians defeating the Dardani.[36] Macedonia and Illyria became Roman protectorates in 168 BC.[37] The Scordisci, a tribe of Celtic origin, most likely subdued the Dardani in the mid-2nd century BC, after which there was no mention of the Dardani for a long time.[38]

Roman period

Macedonia and Illyria became Roman protectorates in 168 BC.[37]

In 97 BC the Dardani are mentioned again, defeated by the Macedonian Roman army.[39] In 88 BC, the Dardani invaded the Roman province of Macedonia together with the Scordisci and the Maedi.[40]

According to Strabo's Geographica (compiled 20 BC–23 AD), they were divided into two sub-groups, the Galabri and the Thunatae.[41]

It seems quite probable that the Dardani actually lost independence in 28 BC thus, the final occupation of Dardania by Rome has been connected with the beginnings of Augustus' rule in 6 AD, when they were finally conquered by Rome. Dardania was conquered by Gaius Scribonius Curio and the Latin language was soon adopted as the main language of the tribe as many other conquered and Romanized.[42]

Aftermath and legacy

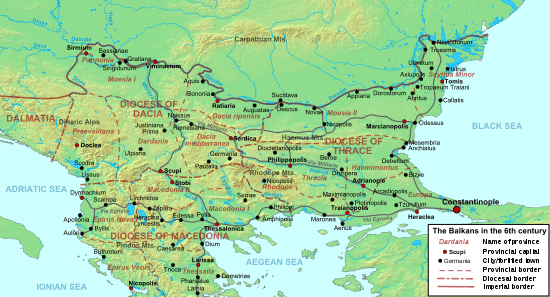

At first, Dardania was not a separate Roman province, but became a region in the province of Moesia Superior in 87 AD.[43] Emperor Diocletian later (284) made Dardania into a separate[43] province with its capital at Naissus (Niš). During the Byzantine administration (in the 6th century), there was a Byzantine province of Dardania that included cities of Ulpiana, Scupi, Stobi, Justiniana Prima, and others.

The Illyrian language disappeared, with almost nothing of it surviving, except for names.[44] The Illyrian tribes in antiquity were subject to varying degrees of Celticization,[45][46] Hellenization,[47] Romanization[48][49] Byzantinization, and finally Slavicisation.

Polity

It is assumed that the Dardanian kingdom was made up of many tribes and tribal groups, confirmed by Strabo.[50] The first and most prominent king of the Dardani was Bardylis[51] who ruled from 385 BC to 358 BC. Bardylis' descendance (and inheritance) is unclear; Hammond believed that Bardylis II was the son of Bardylis,[52] earlier having believed it to have been Cleitus (as per Arrian),[53] while Wilkes believed Cleitus to be the son.[54] Tribal chiefs Longarus and his son Bato took part in the wars[6] against Romans and Macedonians. The Dardanians, in all their history, always had separate domains from the rest of the Illyrians.[55]

The term used for their territory was (Δαρδανική),[56] while other tribal areas had more unspecified terms, such as Autariaton khora (Αὐταριατῶν χώρα), for the "land of Autariatae." Other than that, little to no data[57] exists on the territory of the Dardani prior to Roman conquest, especially on its southern extent.

Culture

According to Ancient Greek and Roman historiography, the tribe was viewed of as "extremely barbaric".[58][59] Claudius Aelianus and other writers wrote that they bathed only three[60] times in their lives. At birth, when they were wed and after they died. Strabo refers to them as wild[61] and dwelling in dirty caves under dung-hills.[62] This however may have had to do not with cleanliness, as bathing had to do with monetary[59] status from the viewpoint of the Greeks. At the same time, Strabo writes that they had some interest in music as they owned and used flutes and corded instruments.[62]

Dardanian slaves or freedmen at the time of the Roman conquest were clearly of Paleo-Balkan origin, according to their personal names.[63] It has been noted that personal names were mostly of the "Central-Dalmatian type".[64]

Language

An extensive study based on onomastics has been undertaken by Radoslav Katičić which puts the Dardani language area in the Central Illyrian area ("Central Illyrian" consisting of most of former Yugoslavia, north of southern Montenegro to the west of Morava, excepting ancient Liburnia in the northwest, but perhaps extending into Pannonia in the north).[65][66]

Notable people

Attested Dardanian rulers:

Rulers attested as Illyrian in ancient sources, considered Dardanian by some modern scholars:

- Bardylis[51] of the Dardani from 385–358 BC

- Audata probably daughter of Bardylis and wife of Philip II married to him after the battle of 358.[68]

- Cleitus, son of Bardylis, 4th century BC[54]

- Bardylis II, probably Cleitus son, 4th century BC[69]

- Bircenna granddaughter of Cleitus[70] and daughter of Bardylis II.[69] She was a wife of Pyrrhus of Epirus.

- Bardylis II, probably Cleitus son, 4th century BC[69]

See also

- Paleo-Balkanic religion

- Prehistory of Southeastern Europe

- Illyria

- List of ancient tribes in Illyria

- Illyrian Wars

References

- "Δαρδάνιοι, Δάρδανοι, Δαρδανίωνες" Dardanioi, Georg Autenrieth, "A Homeric Dictionary", at Perseus

- Latin Dictionary

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 131

the Dardanians ... living in the frontiers of the Illyrian and the Thracian worlds retained their individuality and, alone among the peoples of that region, succeeded in maintaining themselves as an ethnic unity even when they were militarily and politically subjected by the Roman arms [...] and when, towards the end of the ancient world, the Balkans were involved in far-reaching ethnic perturbations, the Dardanians, of all the Central Balkan tribes, played the greatest part in the genesis of the new peoples who took the place of the old

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. p. 205. ISBN 1438129181.

According to ancient sources, the Dardani - variously grouped but probably Illyrians - lived west of present-day Belgrade in present-day Serbia and Montenegro in the third century B.C.E, their homeland in the ancient region of Thrace (and possibly there since the eight century B.C.E).

- Joseph Roisman; Ian Worthington (7 July 2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-4443-5163-7.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 85

Whether the Dardanians were an Illyrian or a Thracian people has been much debated and one view suggests that the area was originally populated with Thracians who then exposed to direct contact with Illyrians over a long period. [..] The meaning of this state of affairs has been variously interpreted, ranging from notions of Thracianization' (in part) of an existing Illyrian population to the precise opposite. In favour of the latter may be the close correspondence of Illyrian names in Dardania with those of the southern 'real' lllyrians to their west, including the names of Dardanian rulers, Longarus, Bato, Monunius and Etuta, and those on later epitaphs, Epicadus, Scerviaedus, Tuta, Times and Cinna.

- Strabo's geography - http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0239

- Hammond 1966, pp. 239–241.

- Stipčević 1989, pp. 38–39.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 144.

- Papazoglu 1969, p. 201.

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 523

- Wilkes 1992, p. 244.

- Orel, Vladimir E. (1998). Albanian Etymological Dictionary. Brill. p. 56. ISBN 978-90-04-11024-3.

- Wilkes, John (1992). The Illyrians. Wiley. p. 244. ISBN 9780631146711.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) "Names of individuals peoples may have been formed in a similar fashion, Taulantii from ‘swallow’ (cf. the Albanian tallandushe) or Erchelei the ‘eel-men’ and Chelidoni the ‘snail-men’. The name of the Delmatae appears connected with the Albanian word for ‘sheep’ delmë) and the Dardanians with for ‘pear’ (dardhë)."

- Elsie, Robert (1998): "Dendronymica Albanica: A survey of Albanian tree and shrub names". Zeitschrift für Balkanologie 34: 163-200 online paper

- Elsie 2015, p. 310.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 145; Crossland 1982, p. 849; Papazoglu 1969, pp. 101–104; Stipčević 1989, pp. 22–23.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 145.

- Appian, The Foreign Wars, III, 1.2

- Lewis, D. M.; Boardman, John (1994). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 428–429. ISBN 978-0-521-23348-4.

- James R. Ashley (1 January 2004). The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359-323 B.C. McFarland. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-7864-1918-0.

- Elizabeth Donnelly Carney (2000). Women and Monarchy in Macedonia. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-8061-3212-9.

- N. G. L. Hammond (1 August 1998). The Genius of Alexander the Great. University of North Carolina Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8078-4744-2.

- Mócsy 2014, p. 9.

- Robert Malcolm Errington (1990). A History of Macedonia. University of California Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-520-06319-8.

- Hammond 1988, p. 253

- Hammond 1988, p. 338

- A history of Macedonia Volume 5 of Hellenistic culture and society, Author: Robert Malcolm Errington, University of California Press, 1990 ISBN 0-520-06319-8, ISBN 978-0-520-06319-8, p. 185

- A history of Macedonia Volume 5 of Hellenistic culture and society, Robert Malcolm Errington, University of California Press, 1990, ISBN 0-520-06319-8, ISBN 978-0-520-06319-8 p. 174

- Hammond 1988, p. 335

- Hammond 1988, p. 404

- Hammond 1988, p. 420

- Hammond 1988, p. 470

- Hammond 1988, p. 491

- Mócsy 2014, p. 10.

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 173.

- Mócsy 2014, p. 12.

- Mócsy 2014, p. 15.

- Wilkes 1992, p. 140

... Autariatae at the expense of the Triballi until, as Strabo remarks, they in their turn were overcome by the Celtic Scordisci in the early third century

- Strabo: Books 1‑7, 15‑17 in English translation, ed. H. L. Jones (1924), at LacusCurtius

- http://www.balkaninstitut.com/pdf/izdanja/B_XXXVII_2007.pdf

- Wilkes 1992, p. 210

Here the old name of Dardania appears as a new province formed out of Moesia, along with Moesia Prima, Dacia (not Trajan's old province but a... Though its line is far from certain there seems little doubt that most of the Dardanians were excluded from Illyricum and were to become a part of the province of Moesia)

- Wilkes 1992, p. 67

Though almost nothing of it survives, except for names, the Illyrian language has figured prominently

- A dictionary of the Roman Empire Oxford paperback reference, ISBN 978-0-19-510233-8, 1995, page 202, "...contact with the peoples of the Illyrian kingdom and at the Celticized tribes of the Delmatae"

- Pannonia and Upper Moesia. A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. A Mocsy, S Frere

- Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, Jennifer Tolbert Roberts, and Sarah B. Pomeroy. A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture. Oxford University Press, p. 255.

- Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province (Duckworth Archaeology) by William Bowden, 2003, page 211: "... in the ninth century. Wilkes suggested that they represented a `Romanized population of Illyrian origin driven out by Slav settlements further north', ..."

- The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (3-Volume Set) by Alexander P. Kazhdan, 1991, page 248, "...were well fortified. In the 6th and 7th C. the romanized Thraco-Illyrian population was forced to settle in the mountains; they reappear ..."

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 445

The assumption that the Dardanian kingdom was composed of a considerable number of tribes and tribal groups, finds confirmation in Strabo's statement about

- Phillip Harding (21 February 1985). From the End of the Peloponnesian War to the Battle of Ipsus. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-521-29949-7.

Grabos became the most powerful Illyrian king after the death of Bardylis in 358.

- Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond (1994). Collected studies. 3. Hakkert. p. 14.

- Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond (1993). Studies concerning Epirus and Macedonia before Alexander. Hakkert. p. 114.

Bardylis' son Cleitus

- Wilkes 1996, p. 120

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 216

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 523

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 187

We have very little information about the territory of the Dardanians before its inclusion in the Roman state

- Aelian; Diane Ostrom Johnson (June 1997). An English translation of Claudius Aelianus' Varia historia. E. Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-8672-0.

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 517

There must have been some reason why it was said of the Dardanians, and not of any other people, that they only bathed three times in their lives ...like the Dardanians', which was applied not to dirty folk, as might be expected, but to the miserly (ἐπὶ τῶν φειδωλῶν)! For the Greeks, obviously, to bathe or not was only a question of expense and financial means.

- Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898) "...whence it is said of the Dardanians, an Illyrian people, that they bathe only thrice in their lives—at birth, marriage, and after death."

- James Oliver Thomson (1948). History of Ancient Geography. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. pp. 249–. ISBN 978-0-8196-0143-8.

- Strabo,7.5, "The Dardanians are so utterly wild that they dig caves beneath their dung-hills and live there, but still they care for music, always making use of musical instruments, both flutes and stringed instruments"

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 224.

- Papazoglu 1978, p. 245.

- Katičić, Radoslav (1964b) "Die neuesten Forschungen über die einhemiche Sprachschist in den Illyrischen Provinzen" in Benac (1964a) 9-58 Katičić, Radoslav (1965b) "Zur frage der keltischen und panonischen Namengebieten im römischen Dalmatien" ANUBiH 3 GCBI 1, 53-76

- Katičić, Radoslav. Ancient languages of the Balkans. The Hague - Paris (1976)

- Wilkes 1992, p. 86

... including the names of Dardanian rulers, Longarus, Bato, Monunius and Etuta, and those on later epitaphs, Epicadus, Scerviaedus, Tuta, Times and Cinna. Other Dardanian names are linked with...

- Heckel 2006, p. 64

- Heckel 2006, p. 86

- Hammond 1988, p. 47

Sources

- Crossland, R. A. (1982). "Linguistic problems of the Balkan area in late prehistoric and early classical periods". In J. Boardman; I. E. S. Edwards; N. G. L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. III (part 1) (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521224969.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elsie, Robert (2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857739322.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1966). "The Kingdoms in Illyria circa 400-167 B.C.". The Annual of the British School at Athens. British School at Athens. 61: 239–253. JSTOR 30103175.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1967). Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198142536.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1988). A History of Macedonia: 336-167 B.C. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814815-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heckel, Waldemar (2006). Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-1210-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, D. M.; Boardman, John (1994). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23348-4.

- Mócsy, András (2014) [1974]. Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. New York: Routledge.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Papazoglu, Fanula (1969). Srednjobalkanska plemena u predrimsko doba. Tribali, Autarijati, Dardanci, Skordisci i Mezi. Djela - Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine. Odjeljenje društvenih nauka (in Croatian). 30. Sarajevo: Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine.

- Papazoglu, Fanula (1978). The Central Balkan Tribes in pre-Roman Times: Triballi, Autariatae, Dardanians, Scordisci and Moesians. Amsterdam: Hakkert.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petrović, Vladimir P. (2006). "Pre-roman and Roman Dardania historical and geographical considerations". Balcanica (37): 7–23.

- Savić, M. M. (2015). "Material culture of Dardan's in pre-roman period". Baština (in Serbian) (39): 67–84.

- Stipčević, Aleksandar (1989). Iliri: povijest, život, kultura [The Illyrians: history and culture] (in Croatian). Školska knjiga. ISBN 9788603991062.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkes, John (1996) [1992]. The Illyrians. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-19807-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)