Cyclone Olivia

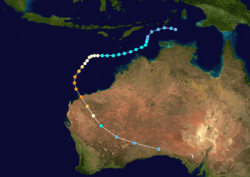

Severe Tropical Cyclone Olivia was a powerful cyclone that produced the highest non-tornadic winds on record on Barrow Island, 408 kilometres per hour (254 mph), breaking the record of 372 km/h (231 mph) on Mount Washington in the United States in April 1934. The 13th named storm of the 1995–96 Australian region cyclone season, Olivia formed on 3 April 1996 to the north of Australia's Northern Territory. The storm moved generally to the southwest, gradually intensifying off Western Australia. On 8 April, Olivia intensified into a severe tropical cyclone and subsequently turned more to the south, steered by a passing trough. On 10 April, Olivia produced the worldwide record strongest gust on Barrow Island, and on the same day the cyclone made landfall near Varanus Island. The storm quickly weakened over land, dissipating over the Great Australian Bight on 12 April.

| Category 4 severe tropical cyclone (Aus scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

Olivia near peak intensity off the coast of Western Australia | |

| Formed | 3 April 1996 |

| Dissipated | 12 April 1996 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 195 km/h (120 mph) 1-minute sustained: 230 km/h (145 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 925 hPa (mbar); 27.32 inHg |

| Fatalities | None reported |

| Damage | At least $47.5 million (1996 USD) |

| Areas affected | Northern Territory and Western Australia |

| Part of the 1995–96 Australian region cyclone season | |

While in its formative stages, Olivia produced light rainfall in the Northern Territory. While offshore Western Australia, the cyclone forced oil platforms to shut down, and the combination of high winds and waves caused heavy damage to oil facilities. Onshore, Olivia's high winds damaged several small mining towns, halting operations. Every house in Pannawonica sustained some damage. One person in the town was injured by flying glass and had to be flown to receive treatment, and nine others were lightly injured. The cyclone also produced heavy rainfall and a localized storm surge. Damage was estimated "in the millions". While the storm was dissipating, rough seas in South Australia killed A$60 million (US$47.5 million) worth of farm-raised tuna at Port Lincoln. The name Olivia was retired after the season.

Meteorological history

In early April 1996, a surge in the trade winds interacted with the monsoon trough to produce an area of convection.[1] On 2 April, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) first identified the system as a low to mid-level low pressure area over Indonesia north of Darwin, Australia. Despite strong wind shear, the system slowly became better organized as it moved southward,[2] aided by improving upper-level outflow.[1] Early on 5 April, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 25S as the system began a westward track,[3] steered by a building mid-level ridge to the south.[2] Shortly thereafter, the BoM upgraded the system to a Category 1 cyclone, designating the storm as Tropical Cyclone Olivia.[2][4]

In the days following Olivia's development, persistent wind shear prevented convection from developing around the center of circulation. By 8 April, an upper-level trough passed to the south of the nascent cyclone, leading to lower shear.[2] Following this, the system had developed sufficiently for the JTWC to upgrade it to a Category 1 equivalent on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale (SSHS), estimating 1 minute sustained winds of 120 km/h (75 mph).[3] Around the same time, the BoM upgraded Olivia to a severe tropical cyclone, assessing similar wind speeds but sustained over 10 minutes.[2][4] After the storm reached this intensity, the mid-level ridge south of the cyclone began to weaken, turning Olivia toward the southwest. By 9 April, the system attained Category 4 intensity according to the BoM as it continued to strengthen.[2] During the afternoon of 9 April, the BoM estimated that Olivia attained its lowest barometric pressure of 925 hPa (mbar), along with 10 minute sustained winds of 195 km/h (120 mph).[2][4] Around 00:00 UTC on 10 April, the JTWC assessed the cyclone to have attained 1 minute winds of 230 km/h (145 mph), equivalent to a Category 4 on the SSHS.[3] By this time, another trough bypassed the cyclone, causing Olivia to turn to the south and accelerate to the southeast. Early on 10 April, data from a nearby weather radar at the Learmonth Airport near Exmouth, Western Australia, showed that the storm had developed a 65 km (40 mi) wide eye.[2]

Late on 10 April, the center of Olivia passed near Barrow Island at peak intensity. Shortly thereafter, the storm passed near Varanus Island as a high-end Category 4 or low-end Category 5 cyclone.[4][5] Within several hours of passing by Varanus Island, Olivia made landfall near Mardie at peak intensity.[2] Shortly thereafter, the storm began to weaken overland. Accelerating to the southeast, the storm became disorganized and winds decreased below hurricane-force.[4] During the afternoon of 11 April, Olivia weakened to a tropical low over southern Australia. It moved over the Great Australian Bight and lost its identity as a gale-force low on 12 April,[2] after it was absorbed by a trough.[6]

Impact and aftermath

As a minimal cyclone in the Timor Sea, Olivia brought minor rainfall and gusty winds to parts of the Northern Territory.[7] On 9 April, the fringes of the storm dropped 84 mm (3.3 in) in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.[8] An oil rig in the Timor Sea recorded a wind gust of 127 km/h (79 mph) during the storm's passage.[7] Offshore, Olivia affected the southern portion of Australia's Northwest Shelf, which had 24 oil and gas facilities.[9] The storm produced large swells up to 21 m (69 ft), in conjunction with extreme wind gusts 265 km/h (165 mph).[2] Waves toppled an oil drilling structure about 40 km (25 mi) northeast of Barrow Island, the first of its kind to fail since the 1980s. The waves also wrecked several anchors for underwater pipelines, although no lines were ruptured. On Barrow Island, the winds knocked over 30 pumpjacks,[9] and several buildings and instruments were damaged, while high waves incurred beach erosion.[8] Damage to offshore platforms was estimated in the millions of dollars.[2]

A group of 17 people, initially considered missing,[10] rode out the storm on the offshore Mackerel Island. Onshore, officials closed a portion of Highway 1 as well as other roads in the area.[11] Ahead of the storm, hundreds of residents in older structures and mobile homes, as well as an aborigine village near Onslow, were ordered to evacuate to safer locations.[12][13] Five iron mines were closed during the storm's passage, forcing the 1,500 workers to return home.[14] The disruptions from the cyclone affected about 340,000 tonnes of lost production.[15] About 800,000 barrels of lost oil production resulted from closed offshore platforms. Oil fields reopened by 14 April.[16]

Moving ashore Western Australia, Olivia produced peak gusts of 257 km/h (160 mph) in Mardie Station,[14] the station's second-highest wind gust from a tropical cyclone.[2] Olivia also produced gusts of 267 km/h (166 mph) at Varanus Island, which was the highest wind gust on record in Australia,[2] until the higher reading on Barrow Island during the storm was confirmed.[17] It broke the previous peak of 259 km/h (161 mph) set by Cyclone Trixie in 1975,[18] and was later matched by Cyclone Vance in 1999.[5] The high winds at Mardie Station damaged the local airport hangar and several windmills.[14] Farther inland, Olivia still produced wind gusts of 158 km/h (98 mph) in Pannawonica, which damaged many roofs, trees, and power lines. The town's police station and medical center lost their roofs during the storm,[19] and every house sustained some damage.[20] Of the 82 houses in the small town, 55 lost their roof. It was estimated that Pannawonica would remain without power for three weeks. One person in town was injured by flying broken glass, who had to be airlifted to Karratha for medical attention. In nearby Yarraloola, nearly every building was damaged, and the roofs of several farm buildings were ripped off. Several other small towns in the region sustained damage to roofs, power lines, and trees,[21] and a 24 year old roadhouse was destroyed along the Fortescue River.[22] Olivia also dropped heavy rainfall, peaking at 167 mm (6.6 in) in Red Hill, although flooding was not significant.[6] The storm also produced a 2 m (6.6 ft) storm surge in localized areas.[7] At the port of Dampier, the storm sank three boats, although no one was aboard.[21] Damage was estimated in the "millions of dollars", according to a local newspaper,[14] and overall, 10 people were injured.[23]

As the remnants of Olivia moved through Australia, they dropped heavy rainfall and brought gusty winds to South Australia. Cape Willoughby recorded gusts of 106 km/h (66 mph) on 12 April, strong enough to knock down tree branches on nearby Kangaroo Island.[8] At Port Lincoln, sediment stirred up by Olivia's remnants killed 60,000 farmed tuna, worth about A$60 million (US$47.5 million). The fish were in cages and died due to abnormally high oxygen levels in the water, caused by Olivia's high winds and rough waves.[24] The remnants of Olivia later brought rainfall to the states of Victoria and Tasmania.[8]

The name "Olivia" was later retired from the list of tropical cyclone names for the Australian region.[25] After the storm's passage, the Royal Australian Air Force flew six generators to Pannawonica after the town was out of power for two nights,[26] and the Western Australian government sent another 13 generators.[27] Residents in the town received counseling to cope with the stress of the storm's aftermath.[21]

Records

At 10:55 UTC on 10 April 1996 along the offshore Barrow Island, an automatic privately operated anemometer recorded a three-second wind gust of 408 km/h (253 mph), at a position 10 m (33 ft) above sea level. The BoM was initially unsure of the veracity of the reading, although a team at the 1999 Offshore Technology Conference presented the reading as the highest wind gust on Earth.[17] In 2009, the World Meteorological Organization Commission for Climatology researched whether Hurricane Gustav in 2008 produced a record 340 km/h (211 mph) gust on Pinar del Rio, Cuba;[28] one committee member recalled the gust set during Olivia, which spurred the investigation. The reading occurred along the western edge of the eyewall, possibly related to mesovortices. Based on other similarly high wind gusts during Olivia – 369 km/h (229 mph) and 374 km/h (232 mph) observed within five minutes of the record gust – the team confirmed that the instrument was observing properly during the storm. The same anemometer also recorded five-minute sustained winds of 178 km/h (111 mph), causing a much greater than normal ratio of gusts to sustained winds. The team confirmed that the instrument was regularly inspected and calibrated, and that the reading was during the passage of the eyewall.[17]

On 26 January 2010, nearly 14 years later, the World Meteorological Organization announced that the wind gust was the highest recorded worldwide. This gust surpassed the previous non-tornadic wind speed of 372 km/h (231 mph) on Mount Washington in the United States in April 1934.[29] The long delay was partly due to the anemometer not being owned by the BoM, and as a result the agency did not enact a follow-up investigation. Despite the high winds, the anemometer and a nearby building were not damaged due to the winds occurring over a very short time.[17]

See also

- 1999 Bridge Creek-Moore tornado – an F5 tornado in the United States which had winds measured at 301 ± 20 mph (484 ± 32 km/h) by a Doppler on Wheels mobile radar

- 2013 El Reno tornado – an enormous tornado in the United States which had winds measured in at 301 mph (484 km/h) by doppler weather radar

References

- Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (April 1996). "Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement" (PDF). 15 (4). Bureau of Meteorology: 2. Retrieved 13 January 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jeff Callaghan (August 1997). "The South Pacific and southeast Indian Ocean tropical cyclone season 1995-96" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (1997). "Cyclone 25S Best Track". United States Navy. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- "The Australian Tropical Cyclone Database" (CSV). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- "Tropical Cyclones in Western Australia - Extremes". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- "Tropical Cyclone Olivia". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- "Northern Territory Cyclones: Tropical Cyclone Olivia". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 1997. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- "Severe Weather Summary - April 1996". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- S.J. Buchan; P.G. Black; R.L. Cohen (1999). The Impact of Tropical Cyclone Olivia on Australia's Northwest Shelf (PDF). Offshore Technology Conference. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- "Small boats in path of cyclone". The Advertiser. 11 April 1996. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Nigel Wilson; Natalie O'Brien (11 April 1996). "Cyclone tears into Pilbara". The Australian. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "International news". Associated Press. 10 April 1996. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Natalie O'Brien; Nigel Wilson (11 April 1996). "Cyclone tears into Pilbara". The Australian. Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Cyclone flattens town". The Daily Telegraph. 11 April 1996. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Kate Askew (12 April 1996). "Cyclone hits output from major mines". The Advertiser. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Some Australian fields set to reopen". Platt's Oilgram Price Report. 15 April 1996. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- J. Courtney; et al. (2012). "Documentation and verification of the world extreme wind gust record: 113.3 m s–1 on Barrow Island, Australia, during passage of tropical cyclone Olivia" (PDF). Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Journal (62). Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- Penelope Green (12 April 1996). "Mop-up begins after near-record cyclone". The Australian. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Cyclone hits Western Australia". Agence France-Presse. 11 April 1996. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Steve Newman (April 14, 1996). "Earthweek: Diary of a Planet". The Daily Gazette. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- Kirsten Stoney (April 12, 1996). "Havoc as cyclone moves inland". The Advertiser. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Devastation as Olivia rips into roadhouse". Hobart Mercury. 12 April 1996. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- John Miller (2007). Australia's Greatest Disasters. Exisle Publishing Limited. p. 80.

- Huw Morgan (19 April 1996). "$60 Million Harvest Lost at Sea". The Advertiser. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (May 5, 2015). List of Tropical Cyclone Names withdrawn from use due to a Cyclone's Negative Impact on one or more countries (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2014). World Meteorological Organization. pp. 2B-1 - 2B-4 (23 - 26). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- "RAAF lights town". Daily Telegraph. April 13, 1996. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Supplies on way". Courier Mail. April 13, 1996. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Beven II, John L; Kimberlain, Todd B; National Hurricane Center (22 January 2009). Hurricane Gustav (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- "Highest surface wind speed - Tropical Cyclone Olivia sets world record". World Record Academy. 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

External links

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC).

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology (TCWC's Perth, Darwin & Brisbane).