Cyclone Bobby

Severe Tropical Cyclone Bobby set numerous monthly rainfall records in parts of the Goldfields-Esperance regions of Western Australia, dropping up to 400 mm (16 in) of rain in February 1995. The fourth named storm of the 1994–95 Australian region cyclone season, Bobby developed as a tropical low embedded within a monsoon trough situated north of the Northern Territory coastline on 19 February. The storm gradually drifted southwestward and later southward under low wind shear, strengthening enough to be assigned the name Bobby by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM). The storm rapidly deepened as it approached the coast of Western Australia, and attained its peak intensity of 925 mbar (hPa; 27.32 inHg) at 0900 UTC on 24 February with 10-minute maximum sustained winds of 195 km/h (120 mph). After making landfall as a somewhat weaker cyclone near Onslow, the remnants of Bobby drifted southeastward, gradually weakening, before dissipating over the southern reaches of Western Australia.

| Category 4 severe tropical cyclone (Aus scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

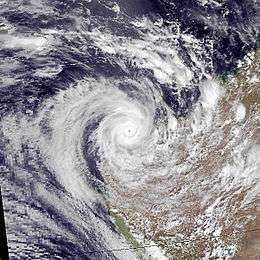

Cyclone Bobby nearing landfall on 24 February 1995 | |

| Formed | 19 February 1995 |

| Dissipated | 27 February 1995 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 195 km/h (120 mph) 1-minute sustained: 205 km/h (125 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 925 hPa (mbar); 27.32 inHg |

| Fatalities | 8 total |

| Damage | $8.5 million (1995 USD) |

| Areas affected | Western Australia, Northern Territory, Australia |

| Part of the 1994–95 Australian region cyclone season | |

Bobby inflicted minor damage throughout Western Australia, dropping copious rainfall and forcing the closure of many facilities and roads. The storm's destruction was most severe in Onslow, where 20 residences suffered damage. Elsewhere, Bobby knocked out power and water supplies, unroofed houses, tore off rain gutters, toppled fences, and smashed windows. The flooding of a 17 km (11 mi) stretch of the Eyre Highway stranded approximately 1000 vehicles, although the backup was later cleared more than a week later. Flooding disrupted mining and drilling operations throughout southwestern Australia, costing the industry upwards of $50 million (1995 AUD; $38.7 million USD). Numerous Australian Army and State Emergency Service (SES) personnel were involved in cleanup and recovery efforts after the cyclone's passage, while power and water service was restored to those cut off during the storm. Overall, the cyclone caused eight deaths and $11 million (1995 AUD; $8.5 million USD) in damage along its course across Western Australia.[nb 1][nb 2]

Meteorological history

The origins of Cyclone Bobby can be traced to a tropical low that formed within a monsoon trough off of the Northern Territory's shores on 19 February 1995. Further organization was initially hindered by strong easterly wind shear as it drifted toward the west-southwest along the northern fringes of a mid-level zonal ridge. The latitudinal ridge was perturbed by a broad frontal system from 21 to 22 February, reducing wind shear around the low and producing favorable conditions for development. Swift tropical cyclogenesis followed as the convection – thunderstorms – strengthened around the system's surface circulation, and the storm was assigned the name Bobby by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) during the early morning hours of 22 February while stationed approximately 500 km (310 mi) north of Port Hedland, making it the fourth named storm of the Australian region cyclone season. Bobby continued to strengthen over the following days while meandering south-southwestward toward the mid-level ridge,[2] and attained Category 1-equivalent intensity on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale at 0000 UTC on 23 February, with 1-minute maximum sustained winds of 120 km/h (75 mph), according to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC).[3][4]

Bobby slowed slightly and moved erratically as it neared the Western Australian coastline, turning southward while rapidly strengthening.[3] It attained its peak intensity of 925 mbar (hPa; 27.32 inHg) at 0900 UTC on 24 February,[2] producing 1-minute sustained winds upwards of 205 km/h (125 mph) and 10-minute winds of 195 km/h (120 mph),[3] equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale or a Category 4 cyclone on the Australian scale.[4][5] Hurricane-force winds' radius around the cyclone's center decreased from 80 km (50 mi) to less than 30 km (19 mi); however, gale-force winds continued to reach as far as 150 km (93 mi) outward from the center, consistent with satellite imagery.[2] The cyclone continued to trek southward under the influence of a northeast-moving frontal system,[6] and made landfall near Onslow at 1800 UTC on 25 February with a minimum atmospheric pressure of 952 mbar (hPa; 28.11 inHg). Bobby persisted for another two days, travelling southward for 24 hours before curving to the southeast and dissipating over southwestern Australia.[2]

Preparations, impact, and aftermath

Before the storm's arrival, approximately 1,000 Aboriginals and individuals living on pastoral stations were evacuated from parts of Pilbara to safer regions;[7] another 7 people were evacuated to the local hospital in Onslow, the local designated evacuation center for the cyclone.[8] The Onslow Airport was closed,[7] as were Karratha's airport, port, and the Griffin oil field managed by Woodside Petroleum.[9] Many other airports, roads, and ports along the Western Australian shoreline were also shut down prior to Bobby's landfall, including the North West Coastal Highway between Onslow and Karratha.[8] In addition, three towns in Western Australia were placed under red alerts.[10]

In Onslow, Bobby damaged or unroofed 20 homes and caused power outages after toppling power lines;[9] in addition, powerful winds tore off rain gutters, damaged radio antennas, toppled fences, and smashed windows.[10] Over 400 mm (16 in) of rain fell there, while numerous February rainfall records were broken in the Goldfields-Esperance region;[11] Onslow received only 95 millimetres (3.7 in) of rain in the six months before Bobby, and annual rainfall in the region averaged 225 to 285 mm (8.9 to 11.2 in); most other parts of Western Australia received 100 to 175 mm (3.9 to 6.9 in) of rainfall from the cyclone.[6] Although 11 fishermen were initially reported missing, all were later verified to be safe. The 61,000-tonne ship Bulk Azores ran aground at Kendrew Island near Dampier while transporting iron ore, though no spillage was noted and the vessel resumed its journey shortly thereafter.[9] Several other boats thought to be missing were driven ashore, although the Lady Pam and Harmony were not found;[8] despite an extensive search involving three helicopters, three airplanes, and numerous police divers,[12] the seven on board were later presumed dead after the Harmony was found capsized and an empty lifeboat from the Lady Pam were located.[13] In Karratha, the cyclone unroofed several homes, toppled trees and power lines, and caused localised flooding.[14] The mining community of Pannawonica also experienced power outages, while elsewhere in Western Australia, the Fortescue, Ashburton, and Gascoyne river drainage basins were flooded.[15] In southern portions of the state, Bobby's remnants flooded the Eyre Highway at Balladonia and 26 km (16 mi) east of Norseman, forcing the closure of a 17 km (11 mi) stretch of road,[12] and stranding 1000 vehicles. Among them included trucks carrying 45 tonnes of stage equipment for two Cliff Richard concerts in Perth, forcing postponement of both,[16] and stage equipment for a performance of the play An Inspector Calls, which was cancelled as a result of the problems.[17]

The cyclone also disrupted gold and mineral mining work in southern Western Australia, closing landing strips at Leinster and Wiluna. Nickel mining near Leinster, mostly from WMC Resources's Mount Keith Mine, was impeded by rainfall which obstructed extraction of ore from the pit. The Super Pit gold mine at Kalgoorlie, meanwhile, was closed after 156 mm (6.1 in) of precipitation fell within a three-day period; all major mines within the vicinity were forced to halt operations. Meanwhile, the Kanowna Belle, New Celebration, Sons of Gwalia, and dozens of other open-pit mines also suspended mining activities due to obstructed roads as well as wet pits and facilities. Several mines suffered fuel shortages, with many roads inaccessible to fuel-transporting vehicles. While the North Rankin A and Goodwyn oil platforms were in the path of Bobby, both facilities escaped damage, and in fact drilled considerably higher amounts as a result of increased demand for gas from utilities on land. The adjacent Perseus platform, however, temporarily shut down operations.[18] Australian gold industry officials estimated total economic disruptions amounted to upwards of $50 million (1995 AUD; $38.7 million USD).[17][nb 2]

Officials coordinated the delivery of food supplies by Australian Army trucks, aircraft, and helicopters, though a military vehicle delivering tarpaulins, radios, and food parcels was caught in mud at Blackheart Creek near Onslow;[19] Australian Army personnel and six State Emergency Service (SES) vehicles were deployed to Onslow for cleanup efforts.[10] Food supplies were airlifted to mostly unpopulated regions of central and eastern Pilbara, where several pastoral stations and Aboriginal localities were cut off by the storm;[12] many of the stations received moderate damage as a result of Bobby.[2] Despite the area's relative isolation, electrical and water service was restored relatively rapidly without issue.[12] The Eyre Highway reopened on 5 March after police, road crews, and SES workers cleared out a jam involving more than 1500 individuals affected by the roadway's flooding.[20] Meanwhile, the government of Australia nullified fuel excises for foreign vessels carrying Australian cargo between parts of Western Australia affected by Bobby due to the lack of usable road and rail routes.[21] In all, the cyclone caused eight deaths, seven out at sea and one due to drowning at Carnarvon,[2] and insured damages totalled $11 million (1995 AUD; $8.5 million USD).[22][nb 2] Due to the cyclone's severity, the name Bobby was retired after the season ended.[23]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- All damage figures are in 1995 Australian dollars (AUD) unless otherwise noted.

- The total was originally reported in Australian dollars. Total converted via the Oanda Corporation website.[1]

References

- "Historical Exchange Rates". Oanda Corporation. 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Shepherd, I.J.; Bate, P.W. (June 1997). "The South Pacific and southeast Indian Ocean tropical cyclone season 1994–95" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine. Bureau of Meteorology. 46 (2): 143–151.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1995 Bobby (1995049S11133). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Schott, Timothy; Landsea, Christopher; et al. (1 February 2012). "The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Bureau of Meteorology. Government of Australia. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Cyclone Bobby brings powerful winds and rare heavy rains to much of Western Australia" (PNG). Weekly Climate Bulletin. Climate Analysis Center. 95 (9). 1 March 1995.

- Graham, D. (26 February 1995). "8 missing as cyclone hits West". The Age. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Biggs, B.; Butler, B.; Taylor, N. (26 February 1995). "Eight missing in cyclone". Herald Sun. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Staff writer (25 February 1995). "Cyclone Bobby pounds West Australian coast". Agence France-Presse. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Graham, D. (27 February 1995). "7 feared lost in ochre sea as cyclone hits WA coast". The Sydney Morning Herald. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- "Tropical Cyclone Bobby". Bureau of Meteorology. Government of Australia. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Russell, M.; Starick, P. (27 February 1995). "Fishermen feared dead in cyclone". The Advertiser. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Staff writer (28 February 1995). "Hopes fade for missing 7 at sea". The Courier-Mail. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Staff writer (25 February 1995). "Towns on alert for cyclone". The Advertiser. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Staff writer (26 February 1995). "Cyclone rips coastal town". The Sunday Mail. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Drislane, J.; Hofmeyer, M. (28 February 1995). "SA father's hope for son lost in cyclone". The Advertiser. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Delvecchio, J. (1 March 1995). "Stage struck in the desert". The Sydney Morning Herald. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Howarth, I. (28 February 1995). "Deluge drenches WA mine output". The Australian Financial Review. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- "Crew missing after cyclone". Hobart Mercury. 27 February 1995. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Staff writer (6 March 1995). "Flood road reopens". Herald Sun. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- Staff writer (8 March 1995). "Flood-ravaged Australia waives fuel tax". The Journal of Commerce. – via LexisNexis (subscription required)

- "Cyclone Bobby, Western Australia 1995". Australian Emergency Management Knowledge Hub. Australian Emergency Management Institute. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (2008). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South Pacific and South-East Indian Ocean (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. p. 28. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

External links

- Joint Typhoon Warning Centre (JTWC)

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology (TCWC's Perth, Darwin & Brisbane)