Cuernavaca Municipality

The Cuernavaca Municipality is one of 36 municipalities in the State of Morelos, Mexico. Located in the northwest of the state, it consists of the City of Cuernavaca, which is the state and municipal capital, as well as other, smaller towns. The population is 366,321 (est. 2015).[2]

Cuernavaca | |

|---|---|

Municipality | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): "City of Eternal Spring" | |

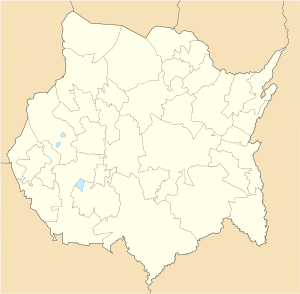

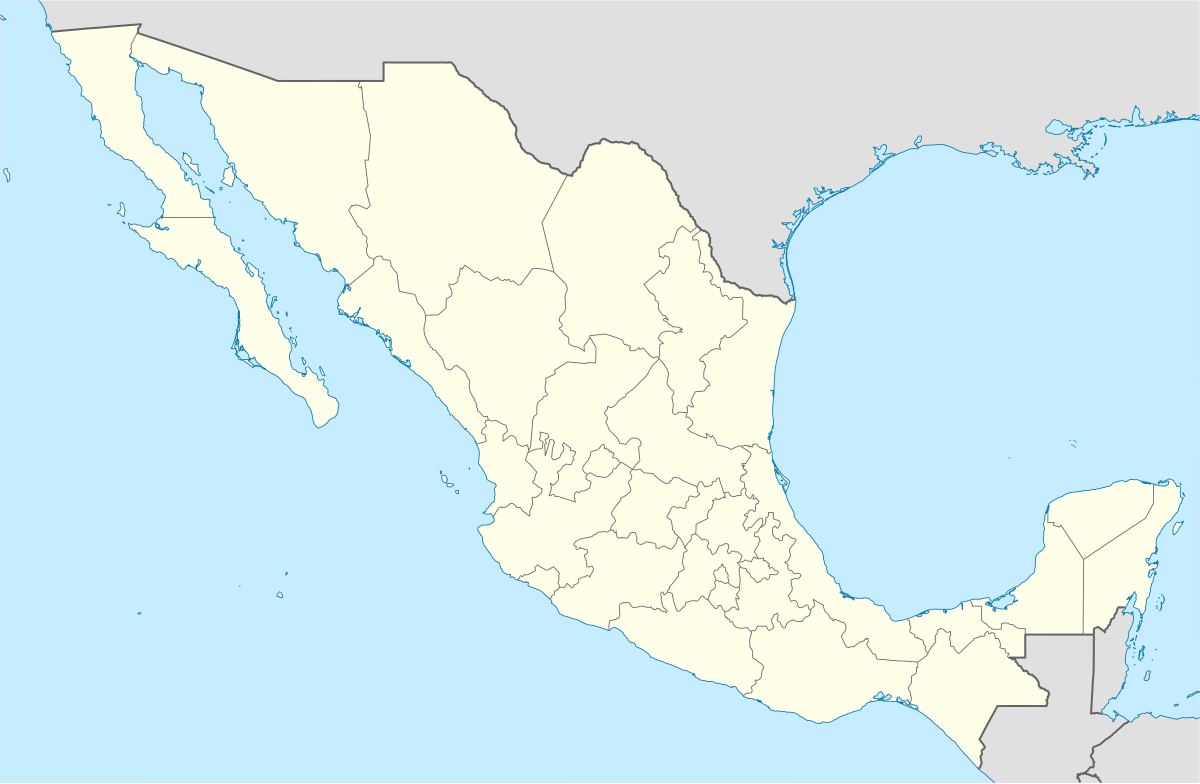

Cuernavaca Location in Mexico  Cuernavaca Cuernavaca (Mexico) | |

| Coordinates: 18°55′07″N 99°14′03″W | |

| Country | |

| State | Morelos |

| Municipal Status | 1821 |

| Government | |

| • Municipal President | Francisco Antonio Villalobos Juntos Haremos Historia[1] |

| Elevation (of seat) | 1,510 m (4,950 ft) |

| Population (est. 2015) Municipality | |

| • Municipality | 366,321[2] |

| • Density | 0.66/km2 (1.7/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Postal code (of seat) | |

| Area code(s) | 777[4] |

| Website | (in Spanish) /Official site |

Geography

Location

The municipality of Cuernavaca is located in the northwest of the state of Morelos, 87.3 kilometres (54.2 mi) south of Mexico City via Mexican Federal Highway 95D. To the north is the municipality of Huitzilac, to the south are the municipalities of Temixco and Xochitepec; Huitzilac, Tepoztlán, and Jiutepec are to the east; and Temixco and the municipality of Ocuilan in the State of Mexico are to the west.[5]

The municipality of Cuernavaca is located at 18°55′N 99°13′W;[6] it is located within the regions of the Neovolcanic Axis and the Sierra Madre del Sur.[5]

Area and land use

The municipality consists of 200.4 km2 (77.37 miles2), which is 4.9% of the total area in Morelos. 5,668 hectares (14,010 acres) are used for agriculture, 8,227 hectares (20,330 acres) for fishing, 5,400 hectares (13,000 acres) for urban areas, and 1,390 hectares (3,400 acres) forest.[5]

Forests are located mainly in the north and along the ravines that run from north to south. Most agriculture is west of the city of Cuernavaca, with smaller area north and east. For the most part agricultural lands have low productivity. Communal lands in Ahuatepec located east of the city, and the ejido of Chipitlán, located to the south of the municipality, are examples of places where irregular settlements are being generated by the illegal subdivision of community plots.[5]

Housing use occupies 85% of the urban area. Of the total area of housing use, 33% is residential, medium-type housing represents 20%, popular housing comprises 45%, and high-density social interest housing occupies 2%. Precarious housing is located mainly in the Patios de la Estación area, on the railroad rights-of-way and in the irregular settlements located on the banks of some canyons and in ejido and communal areas mainly northeast of the municipality.[5]

Mixed use occupies an area of 796 hectares (10.22% of the urban area) and is located mainly on the urban corridors (Avenida Emiliano Zapata, Avenida Álvaro Obregón, Avenida Morelos, Avenida Domingo Diez, Avenida Plan de Ayala-Paseo Cuauhnáhuac, Colonia Río Mayo, Colonia San Diego etc.) the urban center, the urban sub-centers, and the neighborhood centers (Ocotepec, Atlacomulco, Ahuatepec, Amatitlan, Santa María Ahuacatitlán, Tetela, San Jerónimo, Tlaltenango, Acapantzingo, El Calvario, San Antón, Melchor Ocampo, Carolina, Antonio Barona, Palmira, Teopanzolco, etc.)[5]

Commercial use is located in the urban center, urban sub-centers and urban corridors, mixed with other uses, there are also important commercial centers in the city that together occupy an area of 81.76 hectares, 1.05% of the total urban area.[5]

Industrial use occupies an area of 97.71 hectares, 1.25% of the urban area.[5]

Government

The state of Morelos is divided into five federal electoral districts; Cuernavaca is District 1, represented by Alejandro Mojica Toledo (Morena) in the LXIV Legislature of the Mexican Congress (2018-2021).[7]

The state legislature consists of twenty deputies, divided into twelve districts and eight deputies elected by proportional vote. Alejandra Flores Espinoza (PES) repesents District 1 and Hector Javier García Chavez (Morena) repesents District 2 in Cuernavaca.[8]

The government of the municipality of Cuernavaca corresponds to its City Council, which is made up of the Municipal President, a Trustee (Spanish: Sindico) and a council made up of fifteen councilors (Spanish: regidores); ten are elected by majority vote and five by proportional vote. The current municipal president is Francisco Antonio Villalobos Adán and the trustee is Marisol Becerra De La Fuente.[1]

Municipal presidents

- Dates unknown

- José Gabriel Hernández

- Manuel Fiz

- Agustín Muñoz

- Bernabé Castillo

- Juan López

- Juan Alarcón

- Bernardino León y Vélez

- Pedro Patiño Ixtolinque

- Felipe Escorza

- Bernabé L. De Elías (15 years)

- Quirino Manzanares

- Clemente Carpintero

- Cristóbal Figueroa

- Román Vasco

- Crisóforo Albarrán

- Margarito Garduño

- Ismael Velazco

- Benigno Arellano

- Ignacio Flores[1]

- Constitutional presidents

- (1929 - 1930): Salvador S. Saavedra (PRN).

- (1930 - 1931): Ignacio Oliveros

- (1931): Crisóforo Albarran

- (1931 - 1932): Juan Olavarría

- (1933 - 1934): Julio Adán

- (1935 - 1936): Lucio Villasana

- (1937 - 1938): Manuel Gándara Mendieta

- (1939 - 1940): Alfonso Alemán

- (1940 - 1942): Manuel Aranda

- (1943 - 1944): José Cuevas

- (1945 - 1946): Matías Polanco Castro

- (1946 - 1948): Gilberto García Pacheco (PRI)

- (1949 - 1950): Luis Sedano Montes (PRI)

- (1950): Luis Flores Sobral (PRI)

- (1951 - 1952): Luis Alarcón González (PRI)

- (1952 - 1955): Eduardo Díaz Garcilazo (PRI)

- (1955 - 1956): Felipe Rivera Crespo (PRI)[lower-alpha 1]

- (1957 - 1958): Manuel Dehesa (PRI)

- (1958 - 1961): Lorenzo Jiménez (PRI)

- (1961 - 1963): Sergio Jiménez Benítez (PRI)

- (1963 - 1964): Modesto Reyes Ramírez (PRI)

- (1964 - 1967): Valentín López González (PRI)

- (1967 - 1969): Felipe Rivera Crespo (PRI).[lower-alpha 2]

- (1969 - 1970): Crisóforo Ocampo (PRI)

- (1970 - 1973): Ramón Hernández Navarro (PRI)

- (1973 - 1976): David Jiménez González (PRI)

- (1976 - 1979): Porfirio Flores Ayala (PRI)

- (1979 - 1982): José Castillo Pombo (PRI)

- (1982 - 1985): Sergio Figueroa Campos (PRI)

- (1985 - 1988): Juan Salgado Brito (PRI)

- (1988): Eloisa Guadarrama (PRI)

- (1988 - 1990): Julio Mitre (PRI)

- (1990 - 1991): Sergio Estrada Cajigal (PRI)

- (1991 - 1994): Luis Flores Ruiz (PRI)

- (1994 - 1997): Alfonso Sandoval Camuñas (PRI)

- (1997 - 1997): Sara Olivia Parra Téllez (PRI)

- (1997 - 2000): Sergio Estrada Cajigal Ramírez (PAN).[lower-alpha 3]

- (2000): Oscar Sergio Hernández Benítez (PAN)

- (2000 - 2003): José Raúl Hernández Ávila (PAN)

- (2003 - 2006): Adrián Rivera Pérez (PAN)[lower-alpha 4]

- (2006): Norma Alicia Popoca Sotelo (PAN)

- (2006 - 2009): Jesús Giles Sánchez (PAN)[lower-alpha 5]

- (2009): Joaquín Roque González Cerezo (PAN)

- (2009 - 2012): Manuel Martínez Garrigós (PRI)[9]

- (2012): Rogelio Sánchez Gatica (PRI)

- (2012 - 2015): Jorge Morales Barud (CPM-PVEM).[lower-alpha 6]

- (2015 - 2018): Cuauhtémoc Blanco (PSD).[lower-alpha 7]

- (2018): Denisse Arizmendi Villegas (PSD)

- (2019 - present): Francisco Antonio Villalobos Adán (Morena)[lower-alpha 8]

Delegations, towns, and colonies

For administrative purposes, the municipality is divided into eight delegations: Emiliano Zapata, Mariano Matamoros, Lázaro Cárdenas, Benito Juárez, Plutarco Elías Calles, Antonio Barona, Miguel Hidalgo, and Vicente Guerrero. There are 242 municipal assistants.[1]

There are 242 towns and colonies in Cuernavaca, including:

Ahuatepec

Located along the highway to Tepoztlan north of Cuernavaca, the town of es:Ahuatepec was established in precolonial times. The church of San Nicolás Tolentino was founded in the 16th century and holds the remains of Zapatista general Antonio Barona (1886-1915). The neighborhoods Los Limoneros, Jardines de Ahuatepec, La Herradura, México Lindo, Jardines de Zoquipa, Tlaltecuáhuitl, Papayos, el Universo, Villa Santiago, Naranjos, Copalito, Alarcón,Bello Orizonte, Agua Zarca, and others are found in Ahuatepec.[13] The Benedictine monastary Nuestra Señora de los Angeles was founded in 1966.[14] Radio station XHASM-FM (107.7 FM) broadcasts from Ahuatepec.

Buena Vista del Monte

Buenavista del Monte is located 8.5 kilometres (5.3 mi) west of Cuernavaca. It has 910 inhabitants and is located at 1,947 metres (6,388 ft) above sea level.[15]

Acapantzingo

Acapantzingo is divided into different colonias (neighborhoods) and fraccionamientos (subdivisions), including: Colonia San Miguel Acapantzingo, Ejido de Acapantzingo, Fracc. Jacarandas, Fracc. Jardines de Acapantzingo, Fracc. Los Cisos, Pueblo de Acapantzingo, and Tabachines. The Pueblo of Acapantzingo is one of the four original communities that made up the city just before and during the Conquest.[16]

The Ejido of Acapantzingo is 4.83 kilometres (3.00 mi) south of downtown Cuernavaca[17]; it and Tabachines are east of the Cuernavaca freeway bypass; the other neighborhoods are west of it.

There were settlements in today's Acapantzingo as early as 1500 BCE.[16] Bernal Díaz del Castillo mentions that Hernán Cortés[16] (which Díaz del Castillo called "Cuautlavaca.")[18] and his troops camped in the orchards of Acapantzingo the night of April 13, 1521, after the conquest of Cuahuhahuac.[16]

Maximilian I of Mexico established the ″Casa Chica″ for La India Bonita at a finca (estate) in Acapatzingo he called "El Olindo;[19] The estate was burned by troops loyal to Benito Juárez and lay abandoned until it was rebuilt and reopened as the Jardín Etnobotánico de Morelos (Morelos Botanical Garden) and the Museo de Medicina Tradicional y Herbolaria (Museum of Traditional and Herbal Medicine) under the auspiecies of INAH in 1962.[20]

Across from the botanical garden is the parish church of San Miguel Arcangel, built in the 18th century.[20] The feast of St. Michael the Archangel (September 29) is the most important feast day in the neighborhood; other saints venerated are San Isidro (May 15), San Diego Alcalá (November 12), and Our Lady of Guadalupe (December 12).[16]

The Parque Ecológico San Miguel Acapatzingo (Ecological Park) is located at the former site of the state penitentiary, and features a dancing fountain and jogging path,[21] and since 2009 the Hands-on Museo de Ciencias de Morelos (Morelos Science Museum).[22]

The ejido of Acapantzingo is home to the Cuernavaca's spring fair (canceled in 2018 and 2019 due to crime and in 2020 due to the pandemic).[23] There are two universities[24] and an athletic field in Acapantzingo.[16] The gated colony of Los Tabachines surrounds a golf course.[25]

Alarcón

Colonia Alarcón is located 7.2 kilometres (4.5 mi) southeast of Cuernavaca and has 533 inhabitants. It is located at 1,848 metres (6,063 ft) above sea level. 6.94% of the population is indigenous and 3.0% speak an indigenous language.[26]

Amatitlán

Amatitlán is one of the original twelve barrios of Cuernavaca. The Franciscan church of San Luis Obispo dominates this town, which also known for a remnants of a colonial aquaduct.[27] Bernaldino del Castillo, who accompanied Hernán Cortés on the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, founded a sugar cane plantation on 37 hectares of land in Amatitlan in the 16th century; part of this hacienda today form a hotel.[28] The Museo Morelense de Arte Contemporáneo Juan Soriano is also located in Amatitlan.[29]

Antonio Barona

Colonia Antonio Barona is located in the northeastern part of the city, southwest of Federal Highway 95D, 3.98 kilometres (2.47 mi) from the center of the city.[30] It is a large neighborhood, with 3,340 mostly working-class residents in the First Section alone.[31]

The neighborhood was founded while Rodolfo López de Nava was governor of Morelos (1952-1958).[32] A group of citizens from Ahuatepec, led by Enedino and Salvador Montiel Barona, (from the family of General es:Antonio Barona Rojas), supported by lawyer Cristobal Rojas, fought to regain communal lands that had been stolen from them. Although the communalists feared Governor López de Nava, they had secured the support of former president Lázaro Cárdenas, and they managed to seize control of the land.[32] Enedino Montiel Barona was later assassinated.[32][33]

Colonia Barona gained notoriety in May 2020 as the community with the most infections during the COVID-19 pandemic in Morlos (27 of 171 in the municipality and 405 in the state).[34] The state reported 4,533 confirmed cases and 908 deaths on August 10, 2020.[35]

Bosques de la Florida

Colonia Bosques de la Florida is 7.2 kilometres (4.5 mi) southeast of Cuernavaca. It is located at 1,641 metres (5,384 ft) above sea level. 14.29% of the 98 inhabitants are indignous and 9.18% speak an indigenous language.[36]

Buenavista del Monte

Buenavista del Monte is 8.5 kilometres (5.3 mi) west of Cuernavaca, situated at 1,947 metres (6,388 ft) above sea level. Buenavista del Monte is home to 910 people.[37]

Carolina

Colonia Carolina is located northwest of downtown Cuernavaca. It is known for its large market, the colonial-era St. John of the Lakes church (Spanish: San Juan de los Lagos), the athletic complex Unidad Deportiva Miguel Alemán Valdés which includes the city's baseball field, and the cemetery La Leona.[38]

During the 19th century, the street where the market is located was called “Calzada de las Fábricas”, because three factories distilled aguardiente (firewater). One factory-owner had a daughter named "Carolina," hence the name of the distillery and the neighborhood. A second distillery, called "El Rancho" was owned by Ramón del Portillo y Gómez, who also owned the haciendas of Buena Vista, Chiconcuac, El Puente, and Nuestra Señora de los Dolores (in Emiliano Zapata. Agustín Robalo, owner of the hacienda San Luis Obispo, owned the distillery called “San Sabino,” which is located where the bus terminal Transportes Estrella Blanca is located today. All 34 aguardiente and 14 mezcal distilleries, as well as the haciendas that supported them, fell into disuse during the Mexican Revolution.[39]

"La Leona" cemetery was built on land donated by Eugenio de Jesús Cañas (1848-1923), the owner of “Rancho Atzingo.” Cañas also constructed a dam and the first electrical turbine in Cuernavaca in the Barranca Leona (English: Leona Ravine) near El Centenario Street. Ruins of the “Dínamo Viejo” can still be seen from the Centenario Bridge today.[39]

Centenario

Colonia Centenario, located in the north of Cuernavaca, is the home of Centenario Stadium on University Avenue. The Pumas Morelos played at Centarario Stadium in 2013, which holds 14,800 spectators. The stadium opened in 1969, and the sports complex includes a soccer field, athletic track, fronton court, gymnasium, weight room, softball fields, and five multi-use courts for tennis, basketball, volleyball, and fast football.

Chapultepec

Colonia Chapultepec is a residential community south of Avenida Plan de Ayala in eastern Cuernavaca, three km from the center of the city. The 12.844 hectares (31.74 acres) Parque Estatal Urbano Barranca de Chapultepec (founded 1931), with its crystal-clear waters, 250-year-old Montezuma cypress trees, aviary, planitarium, petting zoo, and artificial lake is located in the community.[40][41]

Las Colmenas

Fracc. Las Colmenas is a residential area with 883 inhabitants and 200 commerical establishments along Avenida Palmira south of downtown Cuernavaca. Human Corp SIDH, which specializes in human resources, employs 89% of the people who work in the subdivision.[42]

Ricardo Flores Magón

Colonia Ricardo Flores Magón is located exactly 6.9 kilometres (4.3 mi) west of the geographic center of Cuernavaca and 3.52 kilometres (2.19 mi) southwest of downtown.[43] 4,140 people live in 1,200 homes; 1,000 small retail stores employ 3,000 people. The Unión de Permisionarios del Sistema de Transporte Colectivo Mártires del Río Blanco Ruta 2 is the single largest employer.[44]

Most of the neighborhood is east of Federal Highway 95D (freeway) and north of Federal Highway 160 (Cuauhnahuac Boulevard), including Forum Cuernavaca shopping mall.

Gualupita

Colonia Gualupita is located 3.4 kilometres (2.1 mi) west of the geographic center of Cuernavaca and 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) west of downtown.[45]

Twelve burial sites from three distinct pre-hispanic periods have been found in the area: Early Formative period (c. 1100-900 BCE), Late Formative period (c. 400-200 BCE), and Morelos Post Classic period (c. 1350-1521).[46]

Originally called Teomanalco (Nahutl: "spring of the gods"), Gualupita is located in what was once the forest of Amanalco. An aquaduct, built in 1773 in use until about 1913, brought water to the Villa (small town) of Cuernavaca. The Carmen Romero Rubio park, later renamed Emiliano Zapata park and finally Melchor Ocampo park, opened in 1897.[47]

The colonia also includes Plaza María Félix honoring the film actress and long-time resident of Cuernavaca,[48] as well as a Pullman de Morelos bus station.

Las Granjas

Colonia las Granjas is located west of Federal Highway 95D. It has 249 inhabitants in 67 homes, and there are 15 commercial establishments employing 80 people.[49] The Ex-hacienda de Cortes hotel/spa was founded by Martín Cortés, 2nd Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca in 1542.[50][51]

Jardines de Cuernavaca

939 people live in Jardines de Cuernavaca and 700 work in 60 commercial establishments. Colegio Williams de Cuernavaca, S.C. accounts for 65% of the employees in the zone.[52] The neighborhood includes es:La Tallera, the former home and workshop of social realist, muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros.[53]

Jiquilpan

Colonia Jiquilpan is located 1.09 kilometres (0.68 mi) northeast of downtown Cuernavaca along Avenida Lázaro Cárdenas.[54] The area has 249 residents and 78 commercial establishments, mostly hotels and restaurants, which employ about 600 people.[55]

Loma de los Amates (Loma de la Lagunilla)

Loma de los Amates is also called Loma de la Lagunilla. It has 470 residents, including 6.81% indigenous. It is 1.9 kilometres (1.2 mi) west of Cuernavaca.[56] It is located at 1,550 metres (5,090 ft) above sea level.[57]

Rodolfo López de Nava (Los Naranjos)

Colonia Colonia Rodolfo López de Nava, also called Los Naranjos, has 489 inhabitants, 5.11% of whom are indigenous. The neighborhood is lated at 1,747 metres (5,732 ft) above sea level, 8.3 kilometres (5.2 mi) southeast of Cuernavaca.[58]

Ocotepec

Located north of Federal highway 95D is the town of Ocotepec. Nahua settlements date to the 15th century, when it came under the power of Cuauhnahuac. Three of the original barrios (neighborhoods) date to this era: Candelaria (Tlaneui), founded by Tlahuicas; Dolores (Culhuakan), founded by Acolhuas; and Ramos (Tlakopan), founded by Tecpanecas. The fourth barrio, Santa Cruz (Xalxokotepeazola), was founded in 1970. Ocotepec became part of the Marquessate of the Valley of Oaxaca in 1529. Construction of the Church of the Divino Salvador (Divine Savior) began in 1536, and after independence it was incorporated into the Cuernavaca municipality.

Ocotepec was occupied by North American soldiers during the Mexican–American War in 1847. The church bells were melted for ammunition during the Mexican Revolution, and several residents of Ocoptepec were killed by federalist forces during the fighting. The bell tower was damaged during the September 19, 2017 earthquake.

The town of 15,400 people is known for its Day of the Dead celebrations, held from October 31 to November 2.[59] The town is also known for its delicious barbacoa and the construction of wooden furniture.

The Universidad Nahuatl De Ocotepec (Calmecac cultural center for the study of Nahuatl) is located in Ocotepec.[60]

Lagunilla El Salto

Colonia Lagunilla El Salto is located 3.91 kilometres (2.43 mi) southeast of downtown Cuernavaca.[61] 4,260 people in 1,100 homes live there, and there are 280 commercial establishments that employ 1,000 people.[62] The neighborhood was founded in 1977.[63]

Rancho Cortes

Fraccionmento (Subdivision) Rancho Cortes is located 2.71 kilometres (1.68 mi) northeast of downtown Cuernavaca.[64] It is primarily a residential community; German philosopher Erich Fromm lived there from 1949 to 1974.[65]

San Antón Analco

San Antón Analco is one of the original eleven neighborhoods in Cuernavaca, founded on May 23, 1487.[66] It features a colonial-era church, the cemetery of La Leona, and a waterfall that flows into the ravine of the same name. The neighborhood is located along Avenida Jesús H. Preciado, and access is via the Centennario Bridge.

The Salto de San Anton ("Saint Anthony waterfall″) descends 40 metres (130 ft) straight down a glen. The walls surrounding the waterfall are columnar jointed basalt rock,[66]. Years ago, divers from Acapulco used to dive into the 30-meter pool. According to legend, the falls were formed when a brave warrier did not return from battle, and his fiancée died crying; her hair continued to grow, and the gods cascaded the lovers into a river.[67] Two prehispanic balstic rocks have been found in the area; one is called "Lagarto de San Antón" and can be found outside of the Museo Regional Cuauhnahuac.[67] One can purchase a wide variety of pottery and plants for both house and garden at the many shops immediately surrounding the entrance to the falls,[66] and a local restaurant specializes in quail.[67]

There is another, smaller waterfall, appropriately called El Salto Chico ("the small waterfall") 250 metres north of San Anton.[68]

San Lorenzo Chamilpa

The town of Chamilpa is located 4.36 kilometres (2.71 mi) northwest of the geographic center of the municipality and 3.45 kilometres (2.14 mi) north of Cuernavaca's historical center.[69]

Chamilpa is one of the twelve original towns of Cuernavaca, founded by Antonio de Mendoza on March 30, 1539. The original name was Chiamilpan, which means "chia field." There are two barrios in the town: Olactl ("who hears the movement of water amazed") in the east and Zacanco ("in the place of the grass or pasture") in the west. The 16th-century church is dedicated to Saint Lawrence and his feast is celebrated on August 10.[70]

Every five years there is a celebration to remember the founding of the ecological park located in the town. The region is known for its fresh air and ample green areas.[70][71] Radio station XHCT-FM (95.7 FM) broadcasts from Chamilpa.[72]

Santa María Ahuacatitlán

The village of Santa María Ahuacatitlán is located 3.77 kilometres (2.34 mi) north of the geographic center of the municipality and 4.68 kilometres (2.91 mi) northeast of the historicl center of the city along Mexican Federal Highway 95.[73] 5,700 people live in Santa María Ahuacatitlán, which has commercial establishments employing 2,000 people.[74]

According to city records, Santa María Ahuacatitlán was founded when inhabitants of Cuahnahuac fled the city upon the approach of Hernán Cortés in 1521. Zapatista General Genovevo de la O (1876-1952) and signer of the Plan of Ayala was born in the village and is buried there.[75] From 1952 to 1967, Benedictine monk Gregorio Lemercier (1912-1987), led the monastery of Santa María de la Resurrección.[76]

Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos, Casa Buen Señor operates an orphanage in Santa María Ahuacatitlán.[74] The National Institute of Public Health (INSP) is headquartered in the village.[77]

Satélite

With 7,740 residents, Colonia Satélite is one of the most populous neighborhoods in Morelos. 680 commercial enterprises, mostly small retail establishments, employ 4,000 people. It is one of the lowest-income communities in the state.[78]

Satelite was formed in the 1960s when land in Colonia Chapultepec was expropriated without compensation for construction of the freeway (Federal Highway 95D). Ejidal land was divided into individual lots and construction of homes and businesses began.[33]

In April 2013, Excélsior published an article stating that Satélite was the community with the highest crime rate in Morelos.[79]

Tetela del Monte

Fraccionamiento Tetela del Monte is located 2.98 kilometres (1.85 mi) northwest of downtown Cuernavaca.[80] It is located at 1,789 metres (5,869 ft) above sea level and is a resting spot for pilgrims en route to Chalma, Malinalco, State of Mexico.[81]

The Capilla de los Santos Reyes ("Chapel of the Three Kings"), built between 1530 and 1540, features a 20th-century forged-iron and stone wall designed by British-born artist John Spencer.[81] The bell tower dates from the 17th century.[81] Spencer is buried in the churchyard.[82]

The most important festival in the neighborhood is celebrated on January 6-7, and the second-most important festival is on May 3, the Feast of the Holy Cross, centered around a stone cross erected in the 16th century, and featuring streets filled with colorful flowers, brass bands, and the traditional jump of Chinelos.[81]

Many townspeople cultivate flowers in nurseries featuring a wide variety of plants such as orchids, laceleaf, azaleas, tulips, daisies, lilies, and sunflowers. The most important flower grown is the poinsettia flower, which is exported worldwide.[81]

4,210 people live in Tetela del Monte. There are 290 commercial establishments that employ 2,000 people.[83]

Tlaltenango

Colonia Tlaltenango is located 1.91 kilometres (1.19 mi) north of downtown Cuernavaca along Avenida Emiliano Zapata.[84] The Parque Ecológical Cultural Tlaltenango is located at the Tlaltenango traffic circle located at the junction of Zapata and Calzada de los Reyes.[85] The focus of the cultural center is a house built in the "Cuernavaca-style" in the 1930s; the park was designed by the architect Dalia Mendoza and opened in 2010.[86]

Tlaltenango was orignially a Tlahuica settlement; in 1523 it became the site of conquistador Hernán Cortés's first hacienda.[86] The hacienda soon became a comercial center for gold, silver, and cloth along the Mexico City-Acapulco trade route.[86]

The Chapel of San José, built in 1523, is said to be the oldest church on the American continent. Legend has it that on August 30, 1720, a priest and the mayor found a chest belonging to Doña Agustina Andrade. When the chest was opened andreturned to its owner, they found a small statue of the Virgin Mary inside. The statue performed several miracles, and the Santuario de la Virgen de los Milagros was built adjacent to the San José chapel in 1730.[87][88] The bell tower was built from 1882-1884 and holds one of the largest bells in Morelos.[89] A mural featuring Hernan Cortes, Emiliano Zapata, and the Virgin was painted by Roberto Martínez in the atrium of the church in 1982.[86]

The chapel of San José was built to serve the religious needs of upper-class Peninsulars and Criollos; further north the church of San Jerónimo was built to evangelize the indigenous people.[90]

Since 1720, a street fair has been held from August 30 to September 11; Avenida Emiliano Zapata is closed and hundreds of merchants sell their wares.[91] General Emiliano Zapata donated a silver and gold crown to the statue of Our Lady of Miracles during the fair on September 8, 1914, while the city was under siege. Two years later, troops loyal to Venustiano Carranza stole the crown; Father Nicanor Gómez took the statue to Mexico City, where it stayed until 1919.[89]

Vicente Guerrero

616 people live in Colonia Vicente Guerrero near Avenida Plan de Ayala, east of downtown. There are 95 commercial establishments that employ 900 people. The federal government is the largest single employer in the neighborhood.[92]

Fraccionamiento Universo

Fraccionamiento Universo is located in the Municipality of Cuernavaca, 6.9 kilometres (4.3 mi) southeast of Cuernavaca. There are 1,862 inhabitants including 5.53% indigenous. Universo is 1,635 metres (5,364 ft) above sea level.[93]

Vista Hermosa

Colonia Vista Hermosa is a residential community northeast of downtown. It is known for its many schools, restaurants, hotels, medical centers (including two universities) and an active nightlife, especially on Avenidas San Diego and Río Mayo.[94]

The Teopanzolco archaeological zone is located in the community. Most of the ruins date from the Middle and Post Classic Periods (1350-1521). The largest structure features unusual twin temples, one dedicated to Tlāloc (Aztec god of rain) and the other dedicated to Huītzilōpōchtli (god of war). Two phases of construction are visible, one on top of the other; construction of the second temple was most likely interrupted by the Spanish invasion.[95]

Adjacent to the pyramid site is the Teopanzolco Cultural Center, built by architect Isaac Broid Zajman in 2017 to enhance the relationship with the archeological site and to generate a significant public space for concerts, plays, and other events.[96]

A paved bicycle path extends from Avenida Río Mayo to Avenida San Diego along what was once the city's rail line. The path is popular not only with bicyclists but also joggers, rollerbladers, dog-walkers, and others who want to exercise.[94]

The Catholic parish church María Madre de la Misericordia features stained glass and an altar with colorful contemporary designs.[94]

Climate

Prussian geographer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt nicknamed Cuernavaca the "City of Eternal Spring" during his brief visit in 1804.[97] The climate varies due to the marked differences in altitude since the terrain in which it is located varies between 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) in the north to convert|1,380|m|ft}} above sea level in the south of the municipality. The northern area has a humid temperate climate, and it becomes somewhat warmer and less humid towards the center and south.[98] The rainy season is cloudy, the dry season is partially cloudy, and it is hot throughout the year. During the course of the year, the temperature generally ranges from 10 °C°F to and rarely drops below 7 °C (45 °F) or rises above 34 °C (93 °F).[99]

Cuernavaca's climate is tropical, Köppen climate classification Aw (Tropical savanna climate with dry-winter characteristics).[100] Precipitation is lowest in December (4 millimetres (0.16 in) and highest in July (233 millimetres (9.2 in)), for an average annual of 1,088 millimetres (42.8 in).[100] Living up to its nickname, average annual temperatures vary by only 4.7°C, with May having the warmest average (23.7 °C (74.7 °F)) and January the coolest average (19.0 °C (66.2 °F)).[100]

Cloud cover varies through the year. Skies are clear approximately 6.8 months of the year, from October 30 to May 22, and cloudy for about 5.2 months, from May 22 to October 30.[99] Daylight lasts 11:00 hours on December 21 to 13:16 hours on June 20.[99]

The windiest time of year is the 4.3 months from December 27 to April 29, with an average velocity of 7.8 kilometres (4.8 mi) per hour. Southerly winds predominate from January 11 to July 6, easterly winds from July 6 to October 1, and northerly winds from October 1 to January 11.[99]

Flora and fauna

- Flora

The flora of Cuernavaca is varies according to area:

- North zone: Mesophile mountain; pine and oak forests.[101]

- Extreme south: Induced grasslands and low deciduous forest, represented by tall herbaceous plants such as castor beans and sunflowers.[101]

- In the ravines that are located to the west and in those that cross the city: Gallery forests in humid areas with trees such as ash, jacaranda, plum, willow, amate, and guava.[101] Cuernavaca natives are nicknamed Los Guayabos ("The Guavas").[102]

- Fauna

The fauna of Cuernavaca is made up of white-tailed deer, raccoon, skunk, squirrel, mountain mouse, puma or American lion, Montezuma quail, gallinita del monte, dove, blue magpie, goldfinch, florican mulatto, red spring; rattlesnake, rattlesnake, frogs, and lizards.[101]

See also

References

Footnotes

- Governor of Morelos (1955-1956) and (1970-1976)

- Governor of Morelos (1970-1976)

- Governor of Morelos (2000-2006). First non-PRI municipal president

- Federal senator (2006-2012)

- Federal deputy 2009-2012

- Interim governor of Morelos (1998-2000)

- Governor of Morelos (2018-present)

- [10][11] Villalobos was chosen as a substitute candidate after the original candidate of his party, José Luis Gómez Borbolla, had his registration canceled. After winning the July 2018 election, Villalobos Adan's house was shot at in October, so he decided to stay out of the spotlight from November 2018 until he took office on January 1, 2019.[12]

Citations

- "Cuernavaca". Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- "Cuernavaca (Municipality, Mexico) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map and Location". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- "Código Postal de Cuernavaca Centro(Colonia) en Cuernavaca, Morelos. 62000". micodigopostal.org. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- "Morelos Area Codes - Morelos Mexico Area Code Information". www.areacodehelp.com. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- "CUERNAVACA". Enciclopedia de los Municipios y Delegaciones de México: Morelos. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- "Coordenadas geográficas de Cuernavaca, México - Latitud y longitud". www.geodatos.net. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- "Curricula LXIV". sitl.diputados.gob.mx. H. Congreso de la Union. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "Diputados Morelos". Congreso Morelos (in Spanish). Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- Redacción, La. "Deja Manuel Martínez Garrigós alcaldía de Cuernavaca". launion.com.mx.

- Mariano, Israel. "Es Villalobos alcalde electo de Cuernavaca". El Sol de Cuernavaca.

- http://impepac.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Candidatos-electos-2018.pdf Retrieved Dec 14, 2018

- "Le pusieron precio a mi vida: alcalde electo de Cuernavaca". El Financiero.

- "Ahuatepec Cuernavaca Morelos". web.archive.org. 2 February 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Benedictine monastery seeks to bring contemplative tradition to Mexico". catholicsentinel.org. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Buenavista Del Monte (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Tu Colonia: Acapantzingo "Tierra de Carrizales"". www.diariodemorelos.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "EJIDO DE ACAPANTZINGO (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Estos 11 nombres mexicanos surgieron por malentendidos entre los españoles y los pueblos mesoamericanos". Verne (in Spanish). El Pais. 28 March 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Acapatzingo, discreto refugio real (Morelos)". México Desconocido (in Spanish). 29 July 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "San Miguel Acapantzingo". www.revistanomada.com (in Spanish). 16 March 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Parque Ecologico San Miguel Acapantzingo". Cuernavaca Turistico (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Museo de Ciencias de Morelos". Secretaría de Cultura/Sistema de Información Cultural (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Díaz, Julio (23 January 2020). "Feria de la Primavera Cuernavaca 2020 - Cartelera Oficial". SAPS Grupero (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Universidad Guizar y Valencia" (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020. "Universidad Americana de Morelos". Secretaría de Cultura/Sistema de Información Cultural (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Los Tabachines Club de Golf". www.tabachines.com. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Colonia Alarcón (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Diario de Morelos | Tu colonia: Amatitlán, barrio bravo | @diariodemorelos". web.archive.org. 7 April 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Hacienda Amanalco". www.haciendaamanalco.com. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "El Museo Morelense de Arte Contemporáneo Juan Soriano arrancará actividades el 8 de junio". El Universal (in Spanish). 6 June 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "ANTONIO BARONA (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Colonia Antonio Barona 1ra Secc, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- Guerrero Garro, Paco. "Evidencias Reales". www.facebook.com. Evidencias Reales. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- Reséndiz, Sánchez; Hugo, Víctor (NaN). "Ejidos urbanizados de Cuernavaca". Cultura y representaciones sociales (in Spanish). pp. 67–92. Retrieved August 11, 2020. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Morelos Cruz, Rubicela (4 May 2020). "Cuernavaca, lugar uno en contagios y decesos en Morelos". www.jornada.com.mx (in Spanish). La Jornada. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "SITUACIÓN ACTUAL MORELOS COVID-19 10/08/20". Secretaria de Salud (in Spanish). 30 April 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Colonia Bosques De La Florida (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Buenavista Del Monte (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Tu Colonia: La Carolina {FAMOSA Y EN EL CENTRO}". www.diariodemorelos.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Del cronista: La Carolina". www.diariodemorelos.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Parque Estatal Urbano Barranca de Chapultepec". Secretaría de Desarrollo Sustentable (in Spanish). 23 March 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "10 cosas que desconoces del Parque Ecológico Chapultepec". La Union de Morelos. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "ColoniaFracc Las Colmenas, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "RICARDO FLORES MAGON (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "ColoniaRicardo Flores Magon, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "BARRIO GUALUPITA (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Evans, Susan Toby; Webster, David L. (2000). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-80185-3. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Gualupita: barrio con historia y tradición". www.diariodemorelos.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- González, Héctor Raúl. "Reinstalan busto de María Félix en Cuernavaca". La Unión (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "ColoniaGranjas, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Hacienda de Cortés, un sitio lleno de historia (Morelos)". México Desconocido (in Spanish). 21 July 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Hacienda de Cortes". Morelos Turistico,com. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "ColoniaJardines De Cuernavaca, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "SAPS". www.saps-latallera.org. Retrieved July 15, 2020. "Proyecto Siqueiros: La Tallera". INBA - Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020. "El taller de Siqueiros se convierte en un centro de producción artística | Más Cultura" (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "JIQUILPAN (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "ColoniaJiquilpan, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Loma De Los Amates (loma De La Lagunilla) (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Giovannelli, Nuestro Mexico-Claudio. "Loma de los Amates (Loma de la Lagunilla)". Nuestro Mexico (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Colonia Rodolfo López De Nava (los Naranjos) (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Ruiz, María Fernanda; Lobato, Daniel (26 October 2019). "Ocotepec: todos los días son Día de Muertos". Pie de Página (in Spanish). Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- "Calmecac Nexticpac / Universidad Nahua, Trabajo Colectivo Anahuaca". Alianza Anahuaca (in Spanish). 13 November 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- "LAGUNILLA EL SALTO (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "ColoniaLagunilla El Salto, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "43 aniversario". YouTube. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "FRACC RANCHO CORTES (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- Friedman, Lawrence J. (2014). The Lives of Erich Fromm: Love's Prophet. Columbia University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-231-16259-3. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- "México Travel Club". www.mexicotravelclub.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Tu colonia: Salto de san antón". www.diariodemorelos.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Ordóñez, Ezequiel (1937). ""EL SALTO DE SAN ANTON", CUERNAVACA, MOR" [The San Anton Falls, Cuernavaca, Morelos]. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana (in Spanish). 10 (1/2): 7–23. ISSN 1405-3322. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "PUEBLO DE CHAMILPA (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Paredes, Susana. "Festeja Chamilpa sus 480 años". El Sol de Cuernavaca. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- González, Mónica. "Chamilpa: un espacio natural en Cuernavaca". El Sol de Cuernavaca. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Estaciones de Radio en Morelos". enmedios.com. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "SANTA MARIA AHUACATITLAN (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "ColoniaSanta Maria Ahuacatitlan, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com (in Spanish). Market Data Mexico. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Genovevo de la O". DurangoMas (in Spanish). 12 November 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Nuestros humanistas". www.humanistas.org.mx (in Spanish). Nuestros Humanistas. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Sede Cuernavaca". Portal INSP (in Spanish). Gobierno de Mexico. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Colonia Satelite, Cuernavaca, Morelos". MarketDataMexico. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Colonia Satélite, el sitio con el más alto índice criminal en Morelos". Excélsior (in Spanish). 24 April 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "TETELA DEL MONTE (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Redacción, La. "Tetela del Monte: un pueblo de flores". La Unión (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Tu colonia: Tetela del monte {lugar de las piedras}". www.diariodemorelos.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15,2020. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "ColoniaPueblo Tetela Del Monte, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "TLALTENANGO (Cuernavaca, Morelos)". mexico.PueblosAmerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Parque Tlaltenango » Red de Centros Culturales de Morelos". redcentrosculturales.morelos.gob.mx. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "El Parque Tlaltenango". www.revistanomada.com (in Spanish). 16 March 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Habla, Morelos (9 October 2015). "La historia de Tlaltenango". Noticias de Morelos Habla (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Capilla de San José Tlaltenango y Santuario de la Virgen de los Milagros". programadestinosmexico.com. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Iglesia de Nuestra Senora de los Milagros". Morelos Turistico. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Templo de San Jerónimo en Tlaltenango - Franciscana I". GoAppMX - Tu Guía Turística Interactiva (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Güemes, Helue Núñez. "Cumple 299 años la feria de Tlaltenango". El Sol de Cuernavaca. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "ColoniaVicente Guerrero, Cuernavaca, en Morelos". www.marketdatamexico.com. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Fraccionamiento Universo (Cuernavaca, Morelos) retrieved July 13, 2020

- "Tu Colonia: Vista Hermosa". www.diariodemorelos.com (in Spanish). Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Teopanzolco". Uncovered History. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Teopanzolco Cultural Center / Isaac Broid + PRODUCTORA". ArchDaily. 15 November 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Cuernavaca Remains the City of Eternal Spring – Viva Cuernavaca". Moving to Mexico/News. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "Cuernavaca". www.coaliciones.org. Red de Coaliciones Comunitarias. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "Clima promedio en Cuernavaca, México, durante todo el año - Weather Spark". es.weatherspark.com. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "Clima Cuernavaca: Temperatura, Climograma y Tabla climática para Cuernavaca - Climate-Data.org". es.climate-data.org. Climate-Data.org. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "Flora y fauna de Cuernavaca". www.elclima.com.mx (in Spanish). Vida Alterna. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- Habla, Morelos (14 April 2016). "¿Por qué a los cuernavacenses les dicen 'Los Guayabos'?" [Why are Cuernavacans called "Los Guayabos"?]. Noticias de Morelos Habla (in Spanish). Retrieved August 12, 2020.