Cueca

Cueca (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkweka]) is a family of musical styles and associated dances from Chile, Argentina and Bolivia. In Chile, the cueca holds the status of national dance, where it was officially declared as such by the Pinochet dictatorship on September 18, 1979.[1]

Origins

While cueca's origins are not clearly defined, it is considered to have mostly European Spanish and arguably indigenous influences. The most widespread version of its origins relates it with the zamacueca which arose in Peru as a variation of Spanish Fandango dancing with criollo. The dance is then thought to have passed to Chile and Bolivia, where its name was shortened and where it continued to evolve. Due to the dance's popularity in the region, the Peruvian evolution of the zamacueca was nicknamed "la chilena", "the Chilean", due to similarities between the dances. Later, after the Pacific War, the term marinera, in honor of Peru's naval combatants and because of hostile attitude towards Chile, was used in place of "la chilena." In March 1879 the writer and musician Abelardo Gamarra[2][3] renamed the “chilena” as the “marinera”.[4][5][6][7][8][9] The Marinera, Zamba and the Cueca styles are distinct from each other and from their root dance, the zamacueca.

Another theory is that Cueca originated in the early nineteenth century bordellos of South America, as a pas de deux facilitating partner finding.[10]

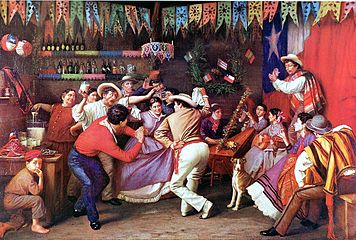

The usual interpretation of this courting dance is zoomorphic: it tries to reenact the courting ritual of a rooster and a hen. The male displays a quite enthusiastic and at times even aggressive attitude while attempting to court the female, who is elusive, defensive and demure. The dance often finishes with the man kneeling on one knee, with the woman placing her foot triumphantly on his raised knee.

In Bolivia, there are many variations throughout the different regions. Cueca styles of La Paz, Potosí and Sucre are the elegant and static versions, whereas in Cochabamba and Tarija the style is much livelier and free. The same could be said with the music where in different regions rhythm and speed slightly differ amongst the regions. While dancing, handkerchiefs are used by both male and female dancers by twirling over the head. It is said the twirling of the handkerchief is a way to lure the woman.[11]

History in Chile

In Chile the cueca was developed and spread in the bars and taverns,[12] which in the nineteenth century were popular centers of entertainment and parties.[13] During Fred Warpole’s stay in Chile between 1844 and 1848 he described some of the characteristics of the dance: guitar or harp accompaniment, drumming of hands or a tambourine to keep the rhythm, high pitched singing and a unique strumming pattern, where the guitarist strums all of the strings, returning each time with a slap on the guitar body.[14]

During the second half of the nineteenth century the cueca was spread to diverse Latin American countries and the dance was known simply as the "chilena" (Chilean).[4] In Argentina the dance was first introduced in Cuyo, which is in the central west of the country close to the border with Chile; there is documented presence of the cueca in this region in approximately 1840. Unlike in the northeast and central west of Argentina in Buenos Aires the dance was known as the "cueca" instead of the "chilena" and there is documentation of the cueca being present in Buenos Aires as early as the 1850s. Similarly to the majority of Argentina the cueca was known as the "chilena" in Bolivia as well.[6] Chilean sailors and adventurers spread the cueca to the coast of Mexico[15] in the cities of Guerrero and Oaxaca, where the dance was also known as the "chilena".[16][17] In Peru the dance transformed into one of the most popular dances during the 1860s and 1870s[18][19] and was also known as the “chilena”.[2][3][20]

Twentieth century

During the twentieth century the cueca was associated with the common man in Chile and through them the dance was spread to the pre-industrialized urban areas where it was adopted by neighborhoods like La Vega, Estación and Matadero, which at the time were located on the outskirts of the city of Santiago.[21] Cueca and Mexican music coexisted with similar levels of popularity in the Chilean countryside in the 1970s.[22][23] Being distinctly Chilean the cueca was selected by the military dictatorship of Pinochet as a music to be promoted.[23]

The cueca was named the national dance of Chile due to its substantial presence throughout the history of the country and announced as such through a public decree in the Official Journal (Diario Oficial) on November 6, 1979.[24] Cueca specialist Emilio Ignacio Santana argues that the dictatorship's appropiation and promotion of cueca harmed the genre.[23] Cueca specialist Emilio Ignacio Santana argues that the dictatorship's appropiation and promotion of cueca harmed the genre.[23] The dictatorship's endorsement of the genre meant according to Santana that the rich landlord huaso became the icon of the cueca and not the rural labourer.[23]

Clothing and dance

The clothing worn during the cueca dance is the traditional Chilean clothes. They wear blue, white, red or black costumes and dresses. The men in the dance wear the huaso's hat, shirts, flannel poncho, riding pants and boots, short jacket, riding boots, and spurs. Women wear flowered dresses. Cueca dancing resembles a rooster-chicken relationship. The man approaches the woman and offers his arm, then the woman accompanies him and they walk around the room. They then face each other and hold their handkerchief in the air, and begin to dance. They never touch, but still maintain contact through facial expressions and movements. During the dance, the pair must wave the white handkerchief.

Basic structure

The basic structure of the cueca is that it is a compound meter in 6

8 or 3

4 and is divided into three sections.

Some differences can be noticed depending on geographical location. There are three distinct variants in addition to the traditional cueca:

- The northern cueca: The main difference with this version is that there is no singing in the accompanying music which is played with only sicus, zamponas, and brass. trumpets, tubas. Also, both the music and the dance are slower. This dance is done during religious ceremonies and carnival.

- The cueca from the central region: This genre is mostly seen in Chile. The guitar, accordion, guitarron, and percussion are the prevailing instruments.

- The Chiloé cueca: This form has the absence of the cuarteta. The seguidilla are repeated and there is a greater emphasis on the way the lyrics are presented by the vocalist.

The cueca nowadays

Currently, the cueca is mainly danced in the countryside, and performed throughout Chile each year during the national holidays in September 18 eve. Cueca tournaments are popular around that time of year.

In Bolivia, Cueca styles vary by region: Cueca Paceña, Cueca Cochabambina, Cueca Chuquisaqueña, Cueca Tarijeña, Cueca Potosina y Cueca Chaqueña. What they have in common is their rhythm, but they differ much in velocity, costumes and style. The Cueca styles of La Paz, Potosí and Sucre are the elegant ones, whereas in Cochabamba and Tarija the style is much more lively. In Bolivia, it is usually called "Cuequita Boliviana"

In Argentina, there are many ways of dancing Cueca. Cueca is mostly danced in the northern and western Argentine provinces of Mendoza, Chaco, Salta, Jujuy, Catamarca, La Rioja etc. Each Argentine province has its own style and way of dancing Cueca.

Cueca in Tarija, Bolivia

Tarija, Bolivia, has a few traditional songs which are accompanied by dances. One of which is the Cueca Tarijena. Although it may have the same name as the dances in the other departments, such as Cueca Pacena which represents La Paz, each department’s dance varies significantly. It is known for being the most upbeat, fun, and playful in comparison to the others which are more tranquil. Additionally, they were the first place to incorporate a violin into our song, thus giving it more flare and excitement. The Cueca, since its origin, has been a source of happiness for the dancers because the music is generally lively and the dances require partners to be excited about dancing with each other.

The interesting thing about Cueca is that it is danced with a handkerchief, and this is how one shows affection for others. Everyone begins the dance with the handkerchief in their right hand and twirls it in circles near their shoulder and then proceeds to waive it by the left side of their waist during certain beats. During the entirety of the dance, the man is attempting to “win over” his partner by showing his dancing talents. The dance demonstrates how Bolivian gender roles remain quite male-dominated. Throughout most the dance, the women simply sway their hips side to side, whereas the men turn in circles and do more complicated movements. This dance is designed for women to show off their beauty and men to demonstrate their talent. The women always follow the male lead because when they are facing each other, it is up to him to decide if he’d like to flirt with his partner by putting his hanker chief near her neck and shoulders, if he’d like to hold the hanker chief behind her neck holding it with both hands, or if he doesn’t want to flirt with her, he will simply continue waiving his handkerchief near his shoulder and waist. This is the determining factor to see if they will dance together in the next part of the song, or if they would need to find other partners. Although we’re in 2018 and most places are working towards equality between women and men, this dance represents the misogyny that still exists today by letting the man choose if he likes his partner with the woman having no say about how she feels.

See also

References

- "La cueca - Memoria Chilena". Memoria Chilena: Portal.

- El Tunante (sábado 8 de marzo de 1879). «Crónica local - No más chilenas». El Nacional. «No más chilenas.—Los músicos y poetas criollos tratan de poner punto final a los bailes conocidos con el nombre de chilenas; quieren que lo nacional, lo formado en el país no lleve nombre extranjero: se han propuesto bautizar, pues, los bailes que tienen el aire y la letra de lo que se lla[ma]ba chilena, con el nombre de Marineras. Tal título tiene su explicación: Primero, la época de su nacimiento será conmemorativa de la toma de Antofagasta por los buques chilenos —cuestión marina. Tendrá la alegría de la marina peruana al marchar al combate —cuestión marina. Su balance gracioso imitará el vaivén de un buque sobre las ajitadas olas —cuestión marina. Su fuga será arrebatadora, llena de brío, endiablada como el combate de las dos escuadras, si llega a realizarse —cuestión marina. Por todas estas razones, los nuevos bailes se llamarán, pues, marineras en vez de chilenas. El nombre no puede ser más significativo, y los músicos y poetas criollos se hallan ocupados en componer para echar a volar por esas calles, letra y música de los nuevos bailes que se bailan, como las que fueron chilenas y que en paz descansen [...] (ortografía original)».

- Gamarra, Abelardo M. (1899). «El baile nacional». Rasgos de pluma. Lima: V. A. Torres. p. 25. «El baile popular de nuestro tiempo se conoce con diferentes nombres [...] y hasta el año 79 era más generalizado llamarlo chilena; fuimos nosotros los que [...] creímos impropio mantener en boca del pueblo y en sus momentos de expansión semejante título y sin acuerdo de ningún concejo de Ministros, y después de meditar en el presente título, resolvimos sustituir el nombre de chilena por el de marinera (ortografía original)».

- Chávez Marquina, Juan Carlos (2014). «Historia de Trujillo - Breve historia de la marinera». www.ilustretrujillo.com. Consultado el 4 de marzo de 2014. «Según el [...] argentino Carlos Vega, esta variante [la cueca chilena] tuvo gran éxito en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, cuyo intercambio musical alcanzó a diversos países de Latinoamérica, incluido Perú. La "cueca" chilena fue conocida en otros países sencillamente como "la chilena", y en Perú, la primera referencia registrada apareció en el periódico El Liberal del 11 de septiembre de 1867, como un canto popular de jarana. Para aquella época, las peculiaridades de la zamacueca adoptaron diversos nombres [...]. "El baile popular de nuestro tiempo se conoce con diferentes nombres [...] y hasta el [18]79 era más generalizado llamarlo chilena; fuimos nosotros los que [...] creímos impropio mantener en boca del pueblo y en momentos de expansión semejante título, y sin acuerdo de ningún Consejo de Ministros, y después de meditar en el presente título, resolvimos sustituir el nombre de chilena por el de marinera [...]" (Gamarra)».

- «La marinera» Archived 2013-10-16 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). www.consuladodelperu.com.mx. s/f. p. 2. Consultado el 2 de noviembre de 2012.

- «Danzas folklóricas argentinas: Coreografías: La cueca - la chilena o norteña» (HTM). www.folkloretradiciones.com.ar. 2005. Consultado el 2007. «Del Perú, alrededor de 1824-25, la zamacueca desciende a Chile, donde es recibida con tal entusiasmo en todas las clases sociales que se convierte en la expresión coreográfica nacional. Los chilenos, a su variante local le llamaron zamacueca chilena que, más tarde por aféresis redujeron la voz zamacueca a sus sílabas finales, cueca. Con el nombre de zamacueca primero y luego con el de cueca chilena, esta danza pantomímica de carácter amatorio pasa a [Argentina] a través de las provincias cuyanas. [En Argentina] el nombre también sufrió modificaciones; en la región de Cuyo quedó el de cueca; para las provincias del noroeste y Bolivia quedó el de chilena. En el Perú se usó también el nombre de chilena como referencia geográfica de la variante de la zamacueca, pero [...] lo cambia por el de marinera [...], nombre con el que perdura hasta hoy».

- Holzmann, Rodolfo (1966). Panorama de la música tradicional del Perú (1.ª edición). Lima: Casa Mozart. «El nombre de "marinera" surgió del fervor patriótico de 1879, año en que don Abelardo Gamarra, "El Tunante", bautizó con él a la hasta entonces "chilena", en homenaje a nuestra Marina de Guerra».

- Hurtado Riofrío, Víctor (2007). «Abelardo Gamarra Rondó "El Tunante"»(HTM). criollosperuanos.com. Consultado el 30 de mayo de 2011. «Los militares chilenos, tropas invasoras de la Restauración, trajeron de regreso a Lima a nuestra zamacueca, con ligeras variantes, así que la empezaron a llamar chilena en los ambientes militares. Pero, Abelardo Gamarra "El Tunante" [...], en 1879, logra hacer desaparecer aquel nombre bautizando a nuestro baile nacional con el nombre de "marinera"».

- COHEN, SUSAN J. The Twenty Piano 'cuecas' Of Simeon Roncal. (bolivia), University of Miami, Ann Arbor, 1981. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global, https://search.proquest.com/docview/303198415.

- Journeyman Pictures reporter Mark Corcoran's documentary with Mario Rojas and Pinochet-era victims' families on YouTube (please disregard political connotations)

- "Traditional Bolivian Music Types: Western Bolivia. Andean Music and Dances".

- Pereira Salas, Eugenio (1941). Los orígenes del arte musical en Chile (PDF). Santiago: Imp. Universitaria. pp. 272-273. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- D'Orbigny, Alcide, II, 1839-1843: 336. Cf. Merino. 1982: 206. D'Orbigny hace referencia a las chinganas que se hallaban en el barrio de El Almendral en Valparaíso durante 1830: «son casas públicas [...] donde se beben refrescos mientras se ve danzar la cachucha, el zapateo, etc., al son de la guitarra y de la voz; es un lugar de cita para todas las clases sociales, [...], pero donde el europeo se encuentra más frecuentemente fuera de lugar».

- Walpole, Fred. I. 1850:105-106. Cf. Merino 1982:207.

- "Cueca." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 Aug. 2011. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/cueca/28125#.

- Vega, Carlos (1986). «La zamacueca (cueca, zamba, chilena, marinera)». Las danzas populares argentinas (Buenos Aires: Instituto Nacional de Musicología 'Carlos Vega') 2: 11-136.

- Stewart, Alex “La chilena mexicana es peruana: Multiculturalism, Regionalism, and Transnational Musical Currents in the Hispanic Pacific” Latin American Music Review-Revista de Musica Latinoamericano, vol. 34, issue 1, 2013, pp. 71-110, http://content.ebscohost.com/ContentServer.asp?EbscoContent=dGJyMMvl7ESeprQ4y9fwOLCmr0%2Bep7JSsq64SLaWxWXS&ContentCustomer=dGJyMPGuskyurK5IuePfgeyx43zx1%2BqE&T=P&P=AN&S=R&D=aph&K=89236509

- León, Javier F. (2014). «Marinera». Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World - Genres: Caribbean and Latin America (en inglés). vol. 9 (1.ª edición). pp. 451-453. ISBN 978-1-4411-4197-2. Consultado el 11 de julio de 2015. «By the 1860s, a Chilean variant [of the zamacueca] known as the chilena or cueca was the most prevalent type of zamacueca in Peru. After the War of the Pacific (1879-83) and the Chilean occupation of the city of Lima, the name of the dance was changed to marinera in honor of the Peruvian navy and it was declared the national dance of Peru».

- Tompkins, William David (s/f). «Afro-Peruvian Traditions». The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music (en inglés). «Probably the most important new national musical genre of the nineteenth century was the zamacueca (or zambacueca), which appeared in coastal Peru not long after 1800. Its choreographic theme, shared with dances derived from it, was a courtship pantomime performed by a man and a woman amid a crowd that accompanied them with rhythmic clapping and supportive shouting. As the dancers advanced and retreated from each other, they rhythmically and provocatively flipped a handkerchief about. The instrumentation varied, but frequently consisted of plucked stringed instruments and a percussive instrument such as the cajon. [...] The zamacueca became popular in many Latin American countries during the mid-1800s, and numerous regional and national variations developed. In the 1860s and 1870s, the zamacueca chilena, a Chilean version of it, was the most popular form in Peru».

- Valle Riestra, Víctor Miguel (≥ 1881). «Testimonio del coronel EP Víctor Miguel Valle Riestra sobre la destrucción de Chorrillos». Consultado el 31 de octubre de 2014. «Las coplas de la [...] chilena, se escuchaban al mismo tiempo que las oraciones de los moribundos»

- Claro Valdés, Samuel, Carmen Peña Fuenzalida y María Isabel Quevedo Cifuentes (1994). Chilena o cueca tradicional (PDF). Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile. p. 543. ISBN 956-14-0340-4. Consultado el 22 de mayo de 2015.

- Dannemann, Manuel (1975). "Situación actual de la música folklórica chilena. Según el Atlas del Folklore de Chile". Revista Musical Chilena (in Spanish). 29 (131): 38–86.

- Montoya Arias, Luis Omar; Díaz Güemez, Marco Aurelio (2017-09-12). "Etnografía de la música mexicana en Chile: Estudio de caso". Revista Electrónica de Divulgación de la Investigación (in Spanish). 14: 1–20.

- Ministerio Secretaría General de Gobierno (06 de noviembre de 1979), «Decreto 23: Declara a la cueca danza nacional de Chile», Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile, consultado el 1 de marzo de 2011.

External links

- Demonstration of Bolivian cueca (and other folk dances specific to the Gran Chaco region) on YouTube