Crondall

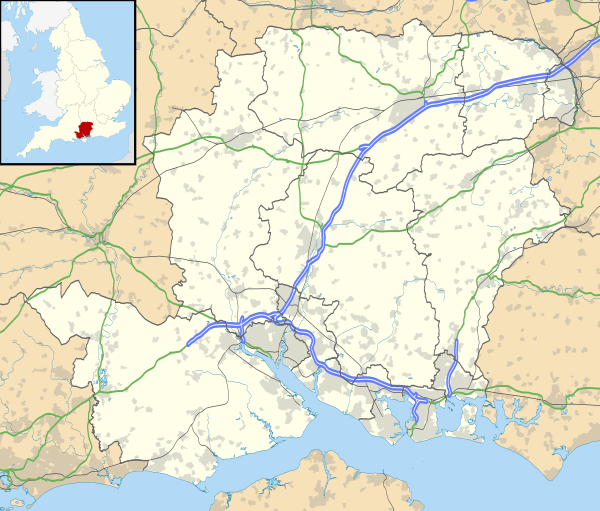

Crondall /krʌndəl/ is a village and large civil parish in the north east of Hampshire in England, in a similar location to the Crondall Hundred surveyed in the Domesday Book of 1086. The village is on the gentle slopes of the low western end of the North Downs range, and has the remains of a Roman villa. Despite the English Reformation, Winchester Cathedral (or its Dean and Chapter) held the chief manors representing much of its land from 975 until 1861. A large collection of Anglo-Saxon and Merovingian coins found in the parish has become known as the Crondall Hoard.

| Crondall | |

|---|---|

A typical village house in Crondall | |

Crondall Location within Hampshire | |

| Population | 1,770 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SU795488 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District |

|

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Farnham |

| Postcode district | GU10 |

| Dialling code | 01252 01276 |

| Police | Hampshire |

| Fire | Hampshire |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament |

|

Toponymy

Various earlier spellings have the intuitive, post-Norman spelling of "u" instead of "o" and the village is still pronounced as it has been for centuries by rooted residents or by those who correctly abstract the sound from 'front': in the 10th century 'Crundelas' was recorded; throughout the 14th century it was 'Crundale'.[2] An Old English crundel was a chalk-pit or lime quarry, and the word has survived in the name of Crondall. The remains of one quarry can still be seen as a large depression on the golf course.

History

Pre-Norman

Crondall's southern boundary is the North Downs along which ran the prehistoric Harrow Way, an ancient unpaved route in Britain which ran from the Cornish tin mines to Dover in Kent. Near this stretch of today's Pilgrims' Way is evidence for neolithic settlements: an Iron Age earthworks at Caesar's Camp.

Remains of Roman settlements have been found close beside the Harrow Way near Barley Pound. Evidence for Roman occupation can be found in the fields as broken tiles and artefacts. In 1817 an intact Roman mosaic pavement was found by a ploughman, 200 yards north of Barley Pound Farm and which is commemorated by a tapestry in the parish church. Coins from the third century were found in 1869.[2]

King Alfred the Great bequeathed the Hundred of Crondall to his nephew Æthelhelm in 885. In 975 it was handed over by King Edgar to the monks at Winchester and remained in their hands until 1539. At this time Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries and within two years Crondall was controlled by the new Dean and Chapter of Winchester Cathedral. Crondall remained in their hands until 1861, when it was taken over by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners.[3]

Crondall Hoard

The Crondall Hoard of one hundred and one old French and Anglo-Saxon coins, two jewelled ornaments, and a chain was found in 1828. Some of these date to the fifth century and ninety seven of the coins are now in the possession of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford.[4] The hoard was deposited after c. 630; of its 101 gold coins, 69 were Anglo-Saxon and 24 were Merovingian or Frankish.[5][6]

Crondall Hundred

The map of Hampshire in the 1722 edition of William Camden's Britannia or Geographical Description of Britain and Ireland shows symbols for major habitation in Farnborough, Cove, Ewshot, Aldershot and Crookham in the Crundhal (Crondall) hundred, a strategic collection of lands with a meeting place at which the wealthy and powerful would convene as needs require, and which came to hold Hundred Courts, a level above the Manorial courts.[7]

The Hundred of Crondall was divided into 'Manors', Itchell, Ewshot, Crokeham/Crookham Well, Feldmead, Dippenhall, Farnborough and Aldershot. These Manors are all mentioned in the records of Winchester Cathedral. All the land within the Hundred was administered by a steward landowner at Crondall on behalf of "the monks of St Swithen" and later on behalf of Winchester Cathedral.

Evolution of the estate

By the early 19th century the Cathedral as manorial owner owned the pick of the surrounding five tithings, the last three of which came to be villages: Crondall, Swanthorpe, and portions of Dippenhall, Church Crookham and Ewshot. This contrasted with lesser agricultural fertility land, much of which was common land and which was no longer connected with the manor.[2]

Itchell Manor

The Giffard/Gifford of Itchel(l) family acquired a Coat of Arms in the Middle Ages. Itchell Manor's gardens (house demolished 1954) were laid out by Capability Brown. A greenhouse, built 1840, is still in use and a Tudor Gateway remains.

John Gifford died seised of the manor in 1563, leaving a son George, then aged 10 years. A third part of the manor passed to his widow who married William Hodges of Weston Sub Edge. In 1579, shortly after George Giffard came of age, Henry Wriothesley, 2nd Earl of Southampton, desiring to add it to his neighbouring estate of Dogmersfield, purchased the estate.[2] After 1628 the estate passed through several hands and in the 18th still had these closes/farmstead localities technically in its freehold: The Hyde, Little Potter's Fore, Earlins, Two Downs, Tanley, Green Park, Park Corner, Dean's Piddle, Old Hop Garden.[2]

Civil War

All Saints' Church in Crondall was a minor parliamentary outpost for much of the English Civil War, guarding the western approaches to Farnham.

Tithe map

A Tithe Map of The Hundred of Crondall, dated 1846, is housed at the Hampshire County Archive in Winchester.

Industry

Crondall has for centuries been rich farming land. A great variety of soils appear in the area because it lies on the edge of the London Basin including chalk, clay and heavy fertile loam. There are many natural springs in the area that were used as watercress beds and for growing osier trees for basket weaving. Some of the baskets were incorporated into the balloon baskets and airship gondolas used by S.F. Cody in his early aviation experiments at Farnborough. For two centuries up to the Second World War, the area was also renowned for hops. For many years Crondall had a brickworks that supplied tiles and brick to local towns.

Architecture

Barley Pound, Motte and Bailey

Barley Pound is a large ring-motte with four baileys and is one of the best examples of a ring and bailey fortress in Hampshire. The fortification may be the "Lidelea Castle" which was mentioned in the Gesta Stephani for 1147, when it was besieged and captured by King Stephen. After its return to Henry of Blois, Bishop of Wincheter it was abandoned in favour of Farnham Castle. Archaeological work has uncovered evidence of an 8-inch thick wall along with a masonry keep.[8]

To the east is Powderham Castle[9] which was a siege-castle to Barley Pound. It too was founded by the Bishop of Winchester and built during The Anarchy in the reign of King Stephen. It was originally an earth and timber ringwork fortress, encased by a ditch and with a counterscarp bank. Due to the demolition of its encasing rampart, the ringwork now resembles a low flat-topped motte. It now also has a dense cover of trees. Excavations on the mound have uncovered post-holes and large flints which may indicate former buildings.

All Saints, Norman Church

The 12th-century Norman parish church, All Saints, which operates as part of the Parish of Crondall and Ewshot, has been called 'The Cathedral of North Hampshire'.[10] It replaced a Saxon church on the same site and the Saxon font remains from that period. The east end of the Nave dates to 1170. The original bell tower was poorly designed for the weight of the bells it housed and by 1657 the whole tower had to be dismantled to prevent its total collapse. In 1659 a new brick tower, modelled on St Matthews in Battersea, was erected at the NE corner of the original structure.

Among notable interior features are an early brass of 1370, the dogtooth mouldings of the chancel arch and the imposing arcades and foliate capitals of the Nave. To date All Saints has undergone two major restorations, the first in 1847 by the architect Benjamin Ferrey and the second in 1871 under the guidance of Sir George Gilbert Scott. In 1995 the "National Association of Decorative and Fine Arts Societies" (NADFAS) declared All Saints to be one of the finest examples of architecture of its style in the country.

There have been reported sightings of the ghosts of Parliamentarian soldiers, including a mounted Roundhead in full battle dress, in the churchyard, following the use of the church as a minor outpost during the English Civil War.[11]

Other buildings

Throughout Crondall there are many well-preserved old houses and cottages. The Plume of Feathers pub is an example of Tudor architecture and was a resting stop on the turnpike to Portsmouth.

Notable visitors and residents

A panoramic view of this part of Hampshire may be gained from Queens View looking from East to West across Crondall. It takes its name from the fact that Queen Victoria admired this view whilst inspecting troops garrisoned at nearby Aldershot "Home of the British Army". Oliver Cromwell is reputed to have stayed in the Plume of Feathers in October 1645, when the siege of Basing House was in progress.[12]

Notable residents include Field Marshall Edwin Bramall, former Head of the British Army and D-Day veteran and Chris Fawkes, a weatherman for the BBC.

Statistics

- According to the 2001 census, 3463 people lived in Crondall.

- There were 1478 households in the ward.

- The parish covers 10.7 square miles (27.7 km²).

Further reading

- Arnold Taylor The Seventeenth-Century Church Towers of Battersea (1639) Staines (1631), Crondall (1659) and Leighton Bromswold (?c. 1640), Architectural History Vol. 27, Design and Practice in British Architecture: Studies in Architectural History Presented to Howard Colvin (1984), pp. 281–296 (article consists of 16 pages) Published by: SAHGB Publications Limited

- Roland P Butterfield Monastery and Manor. The History of Crondall [138p] Printed by EW Langham, Farnham, 1948

- Roland P Butterfield (editor) Ordained in Powder : The Life and Times of Parson White of Crondall Published 1966 by Herald P in Farnham (Sy.)

References

- "Civil Parish population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- William Page, ed. (1911). "Parishes: Crondall". A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 4. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 853.

- "Hampshire Treasures Volume 3 (Hart and Rushmoor) Page 7 – Crondall". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- Grierson, Philip; Blackburn, Mark (2 July 2007). Medieval European Coinage: Volume 1, The Early Middle Ages (5th–10th Centuries). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03177-6., p. 161

- Skingley, Philip, ed. (2014). Coins of England & the United Kingdom: Standard Catalogue of British Coins 2015. Spink & Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-1-907427-43-5., p. 84

- Samuel Lewis' A Topographical Dictionary of England of 1831 Ewshot and Crookham remained in the parish and hundred of Crondall

- Barron, William (1985). The Castles of Hampshire & Isle of Wight. Paul Cave Publications. p. 6. ISBN 0-86146-048-0.

- Not to be confused with Powderham Castle in Devon

- Stooks, C.D. (1905). A History of Crondall and Yateley in the County of Hants, chiefly taken from the churchwardens' accounts and other records in the parish chests. Warren & Son Publishing.

- Scanlan, David (2013). Paranormal Hampshire. Amberley Publishing.

- Plume of Feathers, Crondall Archived 11 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crondall. |

- Crondall at genuki.org

- Old Hants Gazeteer – Crondall through the ages, name derivation

- All Saints and St Mary’s, The Parish of Crondall and Ewshot

- All Saints Church (architectural notes)

- Hampshire County Archive

- Hart Guide: Crondall

- Stained Glass Windows at All Saints Crondall, Hampshire

- Hampshire Treasures Volume 3 (Hart and Rushmoor) pages 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and 26.

- Crondall Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Proposals