First Epistle to the Corinthians

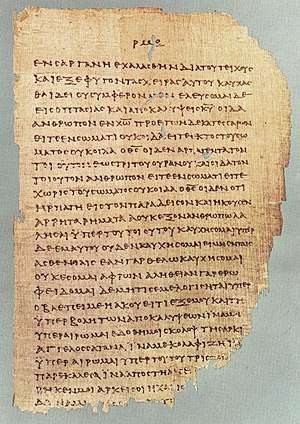

The First Epistle to the Corinthians (Ancient Greek: Α΄ ᾽Επιστολὴ πρὸς Κορινθίους), usually referred to as First Corinthians or 1 Corinthians is a Pauline epistle of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author named Sosthenes, and is addressed to the Christian church in Corinth.[1 Cor.1:1–2] Scholars believe that Sosthenes was the amanuensis who wrote down the text of the letter at Paul's direction.[1] It addresses various issues that had arisen in the Christian community at Corinth and it is composed in a form of Koine Greek.[2][3][4]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

.jpg) |

|

See also

|

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Gospels |

| Acts |

| Acts of the Apostles |

| Epistles |

|

Romans 1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians Galatians · Ephesians Philippians · Colossians 1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy · 2 Timothy Titus · Philemon Hebrews · James 1 Peter · 2 Peter 1 John · 2 John · 3 John Jude |

| Apocalypse |

| Revelation |

| New Testament manuscripts |

Authorship

There is a consensus among historians and theologians that Paul is the author of the First Epistle to the Corinthians (c. AD 53–54).[5] The letter is quoted or mentioned by the earliest of sources, and is included in every ancient canon,[6] including that of Marcion of Sinope. Some scholars point to the epistle's potentially embarrassing references to the existence of sexual immorality in the church as strengthening the case for the authenticity of the letter.[7][1 Cor 5:1ff]

However, the epistle does contain a passage that is widely believed to have been interpolated into the text by a later scribe:

As in all the churches of the saints, women should be silent in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but should be subordinate, as the law also says. If there is anything they desire to know, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church.

— 1 Corinthians 14:34–35, NRSV

Part of the reason for suspecting that this passage is an interpolation is that in some manuscripts, it is placed at the end of Chapter 14, instead of at its canonical location. This kind of variability is generally considered by textual critics to be a sign that a note, initially placed in the margins of the document, has been copied into the body of the text by a scribe. The passage also seems to contradict 11:5, where women are described as praying and prophesying in church.[8]

Furthermore, some scholars believe that the passage 10:1–22 constitutes a separate letter fragment or scribal interpolation because it equates the consumption of meat sacrificed to idols with idolatry, while Paul seems to be more lenient on this issue in 8:1–13 and 10:23–11:1.[9] Such views are rejected by other scholars who give arguments for the unity of 8:1–11:1.[10]

Composition

About the year AD 50, towards the end of his second missionary journey, Paul founded the church in Corinth, before moving on to Ephesus, a city on the west coast of today's Turkey, about 180 miles by sea from Corinth. From there he traveled to Caesarea, and Antioch. Paul returned to Ephesus on his third missionary journey and spent approximately three years there (Acts 19:8, 19:10, 20:31). It was while staying in Ephesus that he received disconcerting news of the community in Corinth regarding jealousies, rivalry, and immoral behavior.[11] It also appears that based on a letter the Corinthians sent Paul (e.g. 7:1), the congregation was requesting clarification on a number of matters, such as marriage and the consumption of meat previously offered to idols.

By comparing Acts of the Apostles 18:1–17 and mentions of Ephesus in the Corinthian correspondence, scholars suggest that the letter was written during Paul's stay in Ephesus, which is usually dated as being in the range of AD 53–57.[12][13]

Anthony C. Thiselton suggests that it is possible that I Corinthians was written during Paul's first (brief) stay in Ephesus, at the end of his Second Journey, usually dated to early AD 54.[14] However, it is more likely that it was written during his extended stay in Ephesus, where he refers to sending Timothy to them (Acts 19:22, 1 Corinthians 4:17).[11]

Structure

.jpg)

_f150v.jpg)

The epistle may be divided into seven parts:[15]

- Salutation (1:1–3)

- Paul addresses the issue regarding challenges to his apostleship and defends the issue by claiming that it was given to him through a revelation from Christ. The salutation (the first section of the letter) reinforces the legitimacy of Paul's apostolic claim.

- Thanksgiving (1:4–9)

- The thanksgiving part of the letter is typical of Hellenistic letter writing. In a thanksgiving recitation the writer thanks God for health, a safe journey, deliverance from danger, or good fortune.

- In this letter, the thanksgiving "introduces charismata and gnosis, topics to which Paul will return and that he will discuss at greater length later in the letter".[16]

- Division in Corinth (1:10–4:21)

- Facts of division

- Causes of division

- Cure for division

- Immorality in Corinth (5:1–6:20)

- Discipline an immoral Brother

- Resolving personal disputes

- Sexual purity

- Difficulties in Corinth (7:1–14:40)

- Doctrine of Resurrection (15:1–58)

- Closing (16:1–24)

- Paul's closing remarks in his letters usually contain his intentions and efforts to improve the community. He would first conclude with his paraenesis and wish them peace by including a prayer request, greet them with his name and his friends with a holy kiss, and offer final grace and benediction:

Now concerning the contribution for the saints: as I directed the churches of Galatia… Let all your things be done with charity. Greet one another with a holy kiss... I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. If any man love not the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be Anathema Maranatha. The grace of the Lord Jesus be with you. My love be with you all in Christ Jesus. Amen.

— (1 Cor. 16:1–24).

Content

Some time before 2 Corinthians was written, Paul paid them a second visit (2 Corinthians 12:14; 13:1) to check some rising disorder (2 Corinthians 2:1; 13:2), and wrote them a letter, now lost (1 Corinthians 5:9). They had also been visited by Apollos (Acts 18:27), perhaps by Peter (1 Corinthians 1:12), and by some Jewish Christians who brought with them letters of commendation from Jerusalem (1 Corinthians 1:12; 2 Corinthians 3:1; 5:16; 11:23).

Paul wrote this letter to correct what he saw as erroneous views in the Corinthian church. Several sources informed Paul of conflicts within the church at Corinth: Apollos (Acts 19:1), a letter from the Corinthians, the "household of Chloe", and finally Stephanas and his two friends who had visited Paul (1:11; 16:17). Paul then wrote this letter to the Corinthians, urging uniformity of belief ("that ye all speak the same thing and that there be no divisions among you", 1:10) and expounding Christian doctrine. Titus and a brother whose name is not given were probably the bearers of the letter to the church at Corinth (2 Corinthians 2:13; 8:6, 16–18).

In general, divisions within the church at Corinth seem to be a problem, and Paul makes it a point to mention these conflicts in the beginning. Specifically, pagan roots still hold sway within their community. Paul wants to bring them back to what he sees as correct doctrine, stating that God has given him the opportunity to be a "skilled master builder" to lay the foundation and let others build upon it (1 Cor 3:10).

Later, Paul wrote about immorality in Corinth by discussing an immoral brother, how to resolve personal disputes, and sexual purity. Regarding marriage, Paul states that it is better for Christians to remain unmarried, but that if they lacked self-control, it is better to marry than "burn" (πυροῦσθαι) which Christians have traditionally thought meant to burn with sinful desires. The Epistle may include marriage as an apostolic practice in 1 Corinthians 9:5, "Do we not have the right to be accompanied by a believing wife, as do the other apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas (Peter)?" (In the last case, the letter concurs with Matthew 8:14, which mentions Peter having a mother-in-law and thus, by inference, a wife.) However, the Greek word for "wife" is the same word for "woman". The Early Church Fathers including Tertullian, Jerome, and Augustine state the Greek word is ambiguous and the women in 1 Corinthians 9:5 were women ministering to the Apostles as women ministered to Christ (cf. Matthew 27:55, Luke 8:1–3), and were not wives,[17] and assert they left their "offices of marriage" to follow Christ.[18]

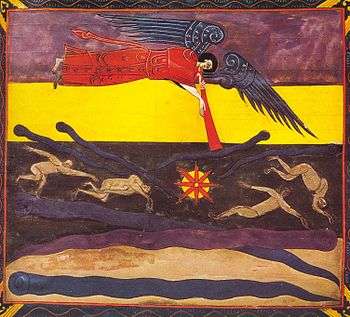

Paul also argues that married people must please their spouses, just as every Christian must please God. The letter is also notable for mentioning the role of women in churches, that for instance they must remain silent (1 Cor. 14:34–35), and yet they have a role of prophecy and apparently speaking tongues in churches (11:2–16). If 14:34–35 is not an interpolation, certain scholars resolve the tension between these texts by positing that wives were either contesting their husband's inspired speeches at church, or the wives/women were chatting and asking questions in a disorderly manner when others were giving inspired utterances. Their silence was unique to the particular situation in the Corinthian gatherings at that time, and on this reading, Paul did not intend his words to be universalized for all women of all churches of all eras.[19] After discussing his views on worshipping idols, Paul finally ends with his views on resurrection. He states that Christ died for our sins, and was buried, and rose on the third day according to the scriptures (1 Cor. 15:3). Paul then asks: "Now if Christ is preached as raised from the dead, how can some of you say that there is no resurrection of the dead?" (1 Cor. 15:12) and addresses the question of resurrection.

Throughout the letter, Paul presents issues that are troubling the community in Corinth and offers ways to fix them. Paul states that this letter is to "admonish" them as beloved children. They are expected to become imitators of Jesus and follow the ways in Christ as he, Paul, teaches in all his churches (1 Cor. 4:14–16).

This epistle contains some well-known phrases, including: "all things to all men" (9:22), "through a glass, darkly" (13:12), and "When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child" (13:11).

Commentaries

St. John Chrysostom, Doctor of the Church, wrote a commentary on 1 Corinthians, formed by 44 homilies.[20]

See also

- 1 Corinthians 10

- 1 Corinthians 11 – on church order

- 1 Corinthians 13 – the tongues of men and angels verse

- 1 Corinthians 15 – on the Resurrection

- Christian headcovering

- Pauline privilege

- Second Epistle to the Corinthians

- Textual variants in the First Epistle to the Corinthians

- Third Epistle to the Corinthians

References

- Meyer's NT Commentary on 1 Corinthians, accessed 16 March 2017

- Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland The text of the New Testament: an introduction to the critical 1995 p52 "The New Testament was written in Koine Greek, the Greek of daily conversation. The fact that from the first all the New Testament writings were written in Greek is conclusively demonstrated by their citations from the Old Testament, .."

- Archibald Macbride Hunter Introducing the New Testament 1972 p9 "How came the twenty-seven books of the New Testament to be gathered together and made authoritative Christian scripture? 1. All the New Testament books were originally written in Greek. On the face of it this may surprise us."

- Herbert Weir Smyth, Greek Grammar. Revised by Gordon M. Messing. ISBN 9780674362505. Harvard University Press, 1956. Introduction F, N-2, p. 4A

- Robert Wall, New Interpreter's Bible Vol. X (Abingdon Press, 2002), p. 373

- "Uncials – Ancient Biblical Manuscripts Online – LibGuides at Baptist Missionary Association Theological Seminary".

- Gench, Frances Taylor (2015-05-18). Encountering God in Tyrannical Texts: Reflections on Paul, Women, and the Authority of Scripture. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. p. 97. ISBN 9780664259525.

- John Muddiman, John Barton, ed. (2001). The Oxford Bible Commentary. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. p. 1130. ISBN 978-0-19-875500-5.

- Walter Schmithals, Gnosticism in Corinth (Nashville: Abingdon, 1971), 14, 92–95; Lamar Cope, "First Corinthians 8–10: Continuity or Contradiction?" Anglican Theological Review: Supplementary Series II. Christ and His Communities (Mar. 1990) 114–23.

- Joop F. M. Smit, About the Idol Offerings (Leuven: Peeters, 2000); B. J. Oropeza, "Laying to Rest the Midrash," Biblica 79 (1998) 57–68.

- "1 Corinthians – Introduction", USCCB

- Corinthians, First Epistle to the, "The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia", Ed. James Orr, 1915.

- Pauline Chronology: His Life and Missionary Work, from Catholic Resources by Felix Just, S.J.

- Anthony C. Thiselton, The First Epistle to the Corinthians (Eerdmans, 2000), 31.

- Outline from NET Bible.org

- Roetzel 1999.

- Tertullian, On Monogamy "For have we not the power of eating and drinking?" he does not demonstrate that "wives" were led about by the apostles, whom even such as have not still have the power of eating and drinking; but simply "women", who used to minister to them in the stone way (as they did) when accompanying the Lord."

- Jerome, Against Jovinianus, Book I "In accordance with this rule Peter and the other Apostles (I must give Jovinianus something now and then out of my abundance) had indeed wives, but those which they had taken before they knew the Gospel. But once they were received into the Apostolate, they forsook the offices of marriage."

- B. J. Oropeza, 1 Corinthians. New Covenant Commentary (Eugene: Cascade, 2017), 187–94; Philip B. Payne, Man and Woman: One in Christ (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009); Ben Witherington, Women in the Earliest Churches (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988);

- "John Chrysostom's homilies on 1 Corinthians" (in English and Latin). Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

Further reading

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph, The Corinthian Mirror: a Study of Contemporary Themes in a Pauline Epistle [i.e. in First Corinthians], Sheed and Ward, London, 1964.

- Erdman, Charles R., The First Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians, Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1966.

- Conzelmann, Hans Der erste Brief an die Korinther, KEK V, Göttingen 1969.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph A., First Corinthians : new translation with introduction and commentary, Anchor Yale Bible, Yale University Press, 2008.

- Robertson, A. and A. Plumber, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the First Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians (Edinburgh 1961).

- Thiselton, Anthony C., The First Epistle to the Corinthians: a commentary on the Greek text NIGTC, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids 2000.

- Yung Suk Kim. Christ's Body in Corinth: The Politics of a Metaphor (Fortress, 2008).

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: First Epistle to the Corinthians |

- A Brief Introduction to 1 Corinthians

- International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: 1 Corinthians

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 150–154.

First Epistle to the Corinthians | ||

| Preceded by Romans |

New Testament Books of the Bible |

Succeeded by Second Corinthians |