Glatiramer acetate

Glatiramer acetate (also known as Copolymer 1, Cop-1, or Copaxone) is an immunomodulator medication currently used to treat multiple sclerosis. Glatiramer acetate is approved in the United States to reduce the frequency of relapses, but not for reducing the progression of disability. Observational studies, but not randomized controlled trials, suggest that it may reduce progression of disability. While a conclusive diagnosis of multiple sclerosis requires a history of two or more episodes of symptoms and signs, glatiramer acetate is approved to treat a first episode anticipating a diagnosis. It is also used to treat relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. It is administered by subcutaneous injection.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Copaxone,[1] Glatopa[2] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.248.824 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C25H45N5O13 |

| Molar mass | 623.657 g·mol−1 |

| | |

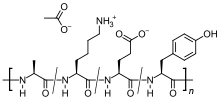

It is a mixture of random-sized peptides that are composed of the four amino acids found in myelin basic protein, namely glutamic acid, lysine, alanine, and tyrosine. Myelin basic protein is the antigen in the myelin sheaths of the neurons that stimulates an autoimmune reaction in people with MS, so the peptide may work as a decoy for the attacking immune cells.

Medical uses

A 2010 Cochrane review concluded that glatiramer acetate had partial efficacy in "relapse-related clinical outcomes" but no effect on progression of the disease.[3] As a result, it is approved by the FDA for reducing the frequency of relapses, but not for reducing the progression of disability.[4]

A 15-year followup of the original trial compared patients who continued with glatiramer to patients who dropped out of the trial. Patients with glatiramer had reduced relapse rates, and decreased disability progression and transition to secondary progressive MS, compared to patients who did not continue glatiramer. However, the two groups were not necessarily comparable, as it was no longer a randomized trial. There were no long-term safety issues.[5]

Adverse effects

Side effects may include a lump at the injection site (injection site reaction) in approximately 30% of users, and aches, fever, chills (flu-like symptoms) in approximately 10% of users.[6] Side effect symptoms are generally mild in nature. A reaction that involves flushing, shortness in breath, anxiety and rapid heartbeat has been reported soon after injection in up to 5% of patients (usually after injecting directly into a vein). These side effects subside within thirty minutes. Over time, a visible dent at the injection site can occur due to the local destruction of fat tissue, known as lipoatrophy, that may develop.

More serious side effects have been reported for glatiramer acetate, according to the FDA's prescribing label, these include serious side effects to the cardiovascular, digestive (including the liver), hematopoietic, lymphatic, musculoskeletal, nervous, respiratory, and urogenital systems as well as special senses (in particular the eyes). Metabolic and nutritional disorders have also been reported; however a link between glatiramer acetate and these adverse effects has not been established.[7]

It may also cause Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate.[8]

Mechanism of action

Glatiramer acetate is a random polymer (average molecular mass 6.4 kD) composed of four amino acids found in myelin basic protein. The mechanism of action for glatiramer acetate is not fully elucidated. It is thought to act by modifying immune processes that are currently believed to be responsible for the pathogenesis of MS. Administration of glatiramer acetate shifts the population of T cells from proinflammatory Th1 T-cells to regulatory Th2 T-cells that suppress the inflammatory response.[9] Given its resemblance to myelin basic protein, glatiramer acetate may act as a decoy, diverting an autoimmune response against myelin. This hypothesis is supported by findings of studies that have been carried out to explore the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a condition induced in several animal species through immunization against central nervous system derived material containing myelin and often used as an experimental animal model of MS. Studies in animals and in vitro systems suggest that upon its administration, glatiramer acetate-specific regulatory T cells (Tregs) are induced and activated in the periphery, inhibiting the inflammatory reaction to myelin basic protein.[10]

The integrity of the blood-brain barrier, however, is not appreciably affected by glatiramer acetate, at least not in the early stages of treatment. Glatiramer acetate has been shown in clinical trials to reduce the number and severity of multiple sclerosis exacerbations.[11]

History

Glatiramer acetate was originally discovered by Michael Sela, Ruth Arnon and Dvora Teitelbaum at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel. Three main clinical trials followed to demonstrate safety and efficacy: The first trial was performed in a single center, double-blind, placebo controlled trial and included 50 patients.[12] The second trial was a two-year, multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial and involved 251 patients.[13] The third trial was a double-blind MRI study involving participation of 239 patients.[14]

Society and culture

Marketing

Glatiramer acetate has been approved for marketing in numerous countries worldwide, including the United States, Israel, Canada and 24 European Union countries.[15][16] Approval in the U.S. was obtained in 1997.[17] Glatiramer acetate was approved for marketing in the U.K. in August 2000, and launched in December.[18] This first approval in a major European market led to approval across the European Union under the mutual recognition procedure. Iran is proceeding with domestic manufacture of glatiramer acetate.[19][20]

Patent status

Novartis subsidiary Sandoz has marketed Glatopa since 2015, a generic version of the original Teva 20 mg formulation that requires daily injection.[21]

Teva developed a long-acting 40 mg formulation, marketed since 2015, which reduced required injections to three per week.[22] In October 2017, the FDA approved a generic version, which is manufactured in India by Natco Pharma, and imported and sold by Dutch firm Mylan.[23][24] In February 2018, Sandoz received FDA approval for their generic version.[25] In parallel with the development and approval processes, the generic competitors have disputed Teva's newer patents, any of which if upheld, would prevent marketing of long-acting generics.[26]

While the patent on the chemical drug expired in 2015,[27] Teva obtained new US patents covering pharmaceutical formulations for long-acting delivery.[28] Litigation from industry competitors in 2016-2017 resulted in the new patents being judged invalid.[29][30] In October 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld the patent invalidation for obviousness.[31][32] The case reflects the larger controversy over evergreening of generic drugs.

References

- "Copaxone® (official Web site)".

- "Glatopa® (official Web site)".

- La Mantia L, Munari LM, Lovati R (May 2010). "Glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD004678. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004678.pub2. PMID 20464733.

- "COPAXONE (glatiramer acetate) solution for subcutaneous injection: Full Prescribing Information (Package insert)" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration.

Label approved on 02/27/2009 (PDF) for COPAXONE, NDA no. 020622

- Ford C, Goodman AD, Johnson K, Kachuck N, Lindsey JW, Lisak R, et al. (March 2010). "Continuous long-term immunomodulatory therapy in relapsing multiple sclerosis: results from the 15-year analysis of the US prospective open-label study of glatiramer acetate". Multiple Sclerosis. 16 (3): 342–50. doi:10.1177/1352458509358088. PMC 2850588. PMID 20106943.

- "Copaxone". MediGuard.

- "COPAXONE (glatiramer acetate for injection)" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2003.

NDA 20-622/S-015/S-015

- Krafchik BR (2011). "Reaction Patterns". In Schachner LA, Hansen RC (eds.). Pediatric Dermatology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1022. ISBN 978-0-7234-3665-2.

- Arnon R, Sela M (1999). "The chemistry of the Copaxone drug" (PDF). Chem. Israel. 1: 12–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-09-07.

- "Copaxone (glatiramer acetate) injection, solution". DailyMed.

- "Copaxone". All About Multiple Sclerosis.

- Bornstein MB, Miller A, Slagle S, Weitzman M, Crystal H, Drexler E, Keilson M, Merriam A, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Spada V (August 1987). "A pilot trial of Cop 1 in exacerbating-remitting multiple sclerosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 317 (7): 408–14. doi:10.1056/NEJM198708133170703. PMID 3302705.

- Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, Ford CC, Goldstein J, Lisak RP, Myers LW, Panitch HS, Rose JW, Schiffer RB (July 1995). "Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group". Neurology. 45 (7): 1268–76. doi:10.1212/WNL.45.7.1268. PMID 7617181.

- Comi G, Filippi M, Wolinsky JS (March 2001). "European/Canadian multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the effects of glatiramer acetate on magnetic resonance imaging--measured disease activity and burden in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis. European/Canadian Glatiramer Acetate Study Group". Annals of Neurology. 49 (3): 290–7. doi:10.1002/ana.64. PMID 11261502.

- McKeage K (May 2015). "Glatiramer Acetate 40 mg/mL in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Review". CNS Drugs. 29 (5): 425–32. doi:10.1007/s40263-015-0245-z. PMID 25906331.

- Comi G, Amato MP, Bertolotto A, Centonze D, De Stefano N, Farina C, et al. (2016). "The heritage of glatiramer acetate and its use in multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis and Demyelinating Disorders. 1 (1). doi:10.1186/s40893-016-0010-2.

- "Copaxone". CenterWatch.

- "Teva's Copaxone approved in UK". The Pharma Letter.

- "Glatiramer Acetate". Tofigh Daru Research and Engineering Company.

- Isayev S, Jafarov T (1 May 2012). "Iran to manufacture multiple sclerosis cure". Trend News Agency.

- "Sandoz announces US launch of Glatopa". Novartis. 2015.

- Silva P (9 October 2015). "New 3-Times-Per-Week Regimen For Teva's Copaxone". Multiple Sclerosis News Today.

- Erman M, Grover D (3 October 2017). "Mylan surges, Teva slumps after FDA okays Copaxone copy". Reuters. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "NATCO's marketing partner Mylan receives final approval of generic glatiramer acetate, for both 20 mg/mL and 40 mg/mL versions". NATCO Pharma (India). 3 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.>

- "Sandoz announces US FDA approval and launch of Glatopa 40 mg/mL". Novartis International AG. February 13, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- "Teva's Copaxone still growing despite patent risks". BioPharmaDive.

- Helfand C. "Copaxone". FiercePharma.

- Decker S (1 September 2016). "Teva loses decision on validity of 302 copaxone patent". Bloomberg Markets.

- Decker S, Flanagan C, Benmeleh Y (30 January 2017). "Teva loses ruling invalidating patents on copaxone drug". Bloomberg Markets.

- "Teva loses patent ruling". Briefcase. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Bloomberg News. September 2, 2017. p. A12. Retrieved June 23, 2018 – via Newspapers.com (Publisher Extra).

- "U.S. appeals court upholds ruling that canceled Teva Copaxone patents". Reuters. October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "In Re: Copaxone Consolidated Cases" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.