Conservation and restoration of vinyl discs

The conservation and restoration of vinyl discs refers to the preventive measures taken to defend against damage and slow degradation, and to maintain fidelity of singles, 12" singles, EP, LP in 45 or 33⅓ rpm disc recordings. LPs are most often in the 12” format, although very early vinyl recordings were 10”. Vinyl LP preservation is generally considered separate from conservation, which refers to the repair and stabilization of individual discs. Commonly practiced in major sound archives and research libraries that house large collections of audio recordings, it is also frequently followed by audiophiles and home record collectors. Because vinyl—a virtually unbreakable light plastic made up of polyvinyl chloride acetate copolymer, or PVC—is considered the most stable of analog recording media, it is seen as less a concern for deterioration than earlier sound recordings made from more fragile materials such as acetate, vulcanite, or shellac. This hardly means that vinyl recordings are infallible, however, and research—both expert and evidential—has shown that the way in which discs are handled and cared for can have a profound effect on their longevity. Though some 45s (7”s) are also made from vinyl, many of them are actually polystyrene—a more fragile medium that is prone to fracturing from internal stress.[1] Still, many of the recommendations for the care of vinyl LPs can be applied to 45s.

Historical development and standards

In 1959—roughly a decade after vinyl LPs first became widely available to consumers—the Library of Congress published Preservation of Sound Recordings (A.G. Pickett and M.M. Lemcoe), the first and most extensive investigation of the deterioration of grooved discs and magnetic tape. Funded by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, the purpose of the investigation was to establish suitable guidelines for the storage and preservation of sound recordings for libraries. Conducted at the Southwest Research Institute of San Antonio, the study involved subjecting sound recordings to a series of lab tests, from accelerated aging to fungal exposure. Though considered the definitive study in the field, the chemical makeup of plastics and how they perform under stress was the primary focus of the report, whereas playback deterioration—a significant concern to sound archivists and record collectors—was excluded from the investigation.[2]

The Preservation and Restoration of Sound Recordings (Jerry McWilliams), published in 1979 by the American Association of State and Local History, did include information about disc wear through playback, and is still a practical source of information on sound recording preservation. A comprehensive manual based on reports gathered from library professionals, sound archivists, audio engineers, and other experts, it included information on such topics as disc damage from frequency of use, stylus wear, and inferior or improperly adjusted equipment.

In 1986 the Association of Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC) Associated Archives (AAA) Committee received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to conduct an in-depth study in order to identify the problems of preservation and access for sound recordings. Their 860-page report, titled Audio Preservation, A Planning Study was published in 1988.[3]

Since the shift from analog to digital recording, research in the preservation of sound recordings has been in serious decline. Gerald L. Gibson, the head of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress expressed his concern on this issue in 1991, by referencing an investigation on the effects of fire on sound and audiovisual recordings as some of the only new research being done on the topic, stating, “Comparatively little is known about the preservation, conservation, aging problems, or properties of sound recordings…virtually no independent work is going on in these areas.” (Gerald L. Gibson, Head of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress, 1991).[4]

Though guidelines and recommendations for the care, handling, and proper storage of vinyl LPs are available from such resources as The Library of Congress and the National Library of Canada, to this date there are no nationally agreed upon standards for audio preservation.[5] In January 2007, a five-page letter was sent to the National Recording Preservation Board at the Library of Congress on behalf of the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) in support of a study on the current state of recorded sound preservation in the United States, stating “the lack of agreed upon standards and commonly accepted best practices presents a major barrier to effective audio preservation.”(Prudence S. Adler, Associate Executive Director and Karla L. Hahn, Director, Office of Scholarly Communication, Association of Research Libraries, Jan. 2007)[5]

Recommendations

Though recommendations for LP preservation differ among professionals, the majority are in agreement on some basic guidelines: discs need to be kept clean, stored in such a way to prevent distortion, and maintained in a stable, climate-controlled environment. Routine maintenance of turntable equipment including regular inspection of the weight, tracking, and condition of the stylus is also advised.

Cleaning

Though proper methods are debated, cleaning is extremely important in maintaining the fidelity of LPs. As Gibson stated, “As with most things in the field, there is very little certainty regarding cleaning. What is known is based on trial-and-error, not upon controlled, scientific study…however, one thing is certain: playing a dirty recording, regardless of its format, is one of the most damaging things you can do to it.”(Gerald L. Gibson, Head of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress, 1991)[6]

It is imperative that LPs be kept free from foreign matter deposits. Oils from fingerprints, adhesives, and soot are damaging, as are air pollutants like cigarette smoke. Even grease from cooking can deposit itself on LPs. Probably the number one contributor to damage, however, is ordinary household dust. Dust can become embedded permanently into the disc's grooves, causing distortion of the transmitting signal, ticks, pops, and inferior sound quality. Vinyl discs can become so dirty and scratched that they are virtually unlistenable.

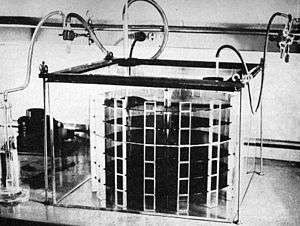

It is recommended that discs be cleaned before—and after—each playback, carbon-fibre brushes are quite effective. Records should be cleaned in a circular motion, in the direction of the grooves. Distilled water (not tap water as it will leave behind mineral deposits) and a soft, lint-free cloth is a common method of cleaning. Another method is to clean the LP on the turntable with a disc cleaning brush (the Discwasher system is frequently recommended by the audio press).[7] A simple "cleaning bath" device called the Spin Clean gives good results, and there are also vacuum machines on the market such as the Nitty Gritty, Keith Monks, Clearaudio, and VPI, which are recommended for more a thorough cleaning.[6] In recent years, ultrasonic cleaning machines from manufacturers such as Klaudio (Korea) and Audio Desk Systeme (Germany) have also been used with great success. The effectiveness of the ultrasonic machines coupled with their premium price tags (both $4,000 US in January 2015) has opened the door for companies to offer professional ultrasonic cleaning at an affordable cost of just a few dollars per record.[8] Another cleaning product recently released called Record Revirginizer uses a polymer that is applied to record surface then left to dry, the polymer is then peeled from the surface taking the microscopic contaminants with it.[9] Though in the past, using alcohol on vinyl LPs was considered safe, experts now caution against it unless absolutely necessary, as alcohol threatens the loss of the plasticizer or stabilizer.[10] As vinyl is often prone to electrostatic charges that cause dust and debris to be attracted to its surface, anti-static products can be used if needed.

Other recommendations for the care, handling, and storage of LPs include the following:[11][12]

Handling

- When possible, use clean, white, lint-free gloves for handling.

- Handle by edge and label areas only, with the third and fourth fingers balancing the label and the thumb supporting the rim.

- Remove from jacket by bowing the jacket open and holding it against the body and letting the LP with its inner sleeve slide out gently (following the same method for removing the inner sleeve).

- Do not expose to air or light unnecessarily. Return LPs to their jackets immediately after playback.

Storing

- Store exactly vertically to prevent warping. Spacers are recommended for every four to six inches.

- Store LPs with other LPs. Avoid mixing with other sizes such as 10″ and 7″ discs. Never use bookends.

- Store on metal shelves (as opposed to wood, which expands and contracts).

- Do not allow LPs to hang over the edge of shelves.

- Remove shrink wrap from dust jackets immediately after acquiring.

- Use polyethylene inner sleeves. Never use PVC sleeves as their chemical makeup is too close to vinyl and may cause imprints or fuse to the LP.[13] Replace paper sleeves as paper deteriorates, leaving oil and paper residue.

- Store in-use LPs at a temperature of 65 to 70 °F (18 to 21 °C). Those in long-term storage should be kept at 45 to 50 °F (7 to 10 °C). Though relative humidity (RH) is considered less an issue for vinyl than other recorded media,[14] it is recommended that LPs be stored at 45 to 50% RH.

Playback equipment

- The stylus tip should be kept clean at all times. A soft, camelhair brush is recommended with a drop of Discwasher solution. Only clean from back to front.

- The stylus should be periodically inspected as it is gradually worn by use. Never play LPs with a worn stylus.

- Maintain proper tracking force. If too high, the stylus will bear down on the groove walls of the LP; if too low, the stylus will bounce in the groove.[15]

Reformatting

As vinyl recordings are known to degrade after repeated playback, preservation copying is recommended for archival purposes. This is especially true for rare recordings or those that have special value. A general guideline is to digitise the recording using the appropriate stylus, tracking weight, equalisation curve and other playback parameters and use high-quality analogue-to-digital converters.[16] A service copy of the recording can then be created (on CD or other format) from the preservation master. A second option is to create three copies, the second copy acting as a duplicating master and the third for public use.

See also

- Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project

- Gramophone record

- LP album

- National Recording Preservation Board

- Phonograph

- Preservation (library and archival science)

- Sound recording and reproduction

- Laser turntable

References

- McWilliams, Jerry. The Preservation and Restoration of Sound Recordings, page 42. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1979. , page 42

- Pickett, A. G., and M. M. Lemcoe. Preservation and Storage of Sound Recordings, page iv. Washington: Library of Congress, 1959.

- Swartzburg, Susan G. Preserving Library Materials: A Manual," page 201. N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1995.

- Gibson, Gerald D. “Preservation and Conservation of Sound Recordings,” page 27 in Conserving and Preserving Materials in Nonbook Formats. Henderson, Kathryn L. and William T., editors. Urbana-Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 1991.

- Association of Research Libraries, Letter to National Recording Preservation Board Archived 2007-02-05 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress

- Gibson, Gerald D. “Preservation and Conservation of Sound Recordings,” page 32 in Conserving and Preserving Materials in Nonbook Formats. Henderson, Kathryn L. and William T., editors. Urbana-Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 1991.

- McWilliams, Jerry. The Preservation and Restoration of Sound Recordings, page 60. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1979.

- Stereophile review of Audio Desk Systeme Vinyl Cleaner Websites for professional ultrasonic cleaning service

- Queensland university student restores retro records Official Website

- Gibson, Gerald D. “Preservation and Conservation of Sound Recordings,” page 33 in Conserving and Preserving Materials in Nonbook Formats. Henderson, Kathryn L. and William T., editors. Urbana-Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 1991.

- Cylinder, Disc, and Tape Care in A Nutshell, Library of Congress

- The Preservation of Recorded Sound Materials, National Library of Canada

- Gibson, Gerald D. “Preservation and Conservation of Sound Recordings,” page 34 in Conserving and Preserving Materials in Nonbook Formats. Henderson, Kathryn L. and William T., editors. Urbana-Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois, Graduate School of Library and Information Science, 1991.

- McWilliams, Jerry. The Preservation and Restoration of Sound Recordings, page 42. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1979.

- McWilliams, Jerry. The Preservation and Restoration of Sound Recordings, page 74. Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1979.

- Guidelines on the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects (IASA TC04) International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives 2009.

External links

- Association for Recorded Sound Collections (ARSC)

- International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA)

- The Care and Handling of Recorded Sound Materials. Updated version; original: St.-Laurent, Gilles. "Preservation of Recorded Sound Materials." ARSC Journal 23, no. 2 (December 1991): 425-436.

- Association of Research Libraries: Pictorial Guide to Sound Recording Media

- The Preservation of Recorded Sound Materials, National Library of Canada

- Cylinder, Disc, and Tape Care in A Nutshell, Library of Congress

- Audio Archiving, Current Issues and Selected Readings, Syracuse University Library