Clipper architecture

The Clipper architecture is a 32-bit RISC-like instruction set architecture designed by Fairchild Semiconductor. The architecture never enjoyed much market success, and the only computer manufacturers to create major product lines using Clipper processors were Intergraph and High Level Hardware. The first processors using the Clipper architecture were designed and sold by Fairchild, but the division responsible for them was subsequently sold to Intergraph in 1987; Intergraph continued work on Clipper processors for use in its own systems.[1]

The Clipper architecture used a simplified instruction set compared to earlier CISC architectures, but it did incorporate some more complicated instructions than were present in other contemporary RISC processors. These instructions were implemented in a so-called Macro Instruction ROM within the Clipper CPU. This scheme allowed the Clipper to have somewhat higher code density than other RISC CPUs.

Versions

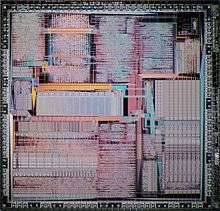

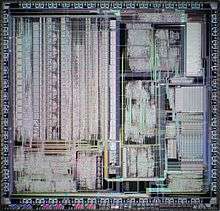

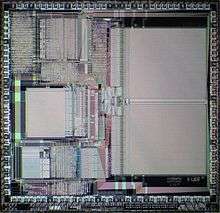

The initial Clipper microprocessor produced by Fairchild was the C100, which became available in 1986. This was followed by the faster C300 from Intergraph in 1988. The final model of the Clipper was the C400, released in 1990, which was extensively redesigned to be faster and added more floating-point registers. The C400 processor combined two key architectural techniques to achieve a new level of performance — superscalar instruction dispatch and superpipelined operation.

While many processors of the time used either superscalar instruction dispatch or superpipelined operation, the Clipper C400 was the first processor to use both.[2]

Intergraph started work on a subsequent Clipper processor design known as the C5, but this was never completed or released. Nonetheless, some advanced processor design techniques were devised for the C5, and Intergraph was granted patents on these. These patents, along with the original Clipper patents, have been the basis of patent-infringement lawsuits by Intergraph against Intel and other companies.[3]

Unlike many other microprocessors, the Clipper processors were actually sets of several distinct chips. The C100 and C300 consist of three chips: one central processing unit containing both an integer unit and a floating point unit, and two cache and memory management units (CAMMUs), one responsible for data and one for instructions. The CAMMUs contained caches, translation lookaside buffers, and support for memory protection and virtual memory. The C400 consists of four basic units: an integer CPU, an FPU, an MMU, and a cache unit. The initial version used one chip each for the CPU and FPU and discrete elements for the MMU and cache unit, but in later versions the MMU and cache unit were combined into one CAMMU chip.

Registers and instruction set

The Clipper had 16 integer registers (R15 was used as stack pointer), 16 floating-point registers (limited to 8 in early implementations), plus a program counter (PC), a processor status word (PSW) containing ALU and FPU status flags and trap enables, and a system status word (SSW) containing external interrupt enable, user/supervisor mode, and address translation control bits.

User and supervisor mode had separate banks of integer registers. Interrupt handling consisted of saving the PC, PSW, and SSW on the stack, clearing the PSW, and loading the PC and SSW from a memory trap vector.

The clipper was a load/store architecture, where arithmetic operations could only specify register or immediate operands. The basic instruction "parcel" was 16 bits: 8 bits of opcode, 4 bits of source register, and 4 bits of destination register. Immediate-operand forms allowed 1 or 2 following instruction parcels to specify a 16-bit (sign-extended) or 32-bit immediate operand. The processor was uniformly little-endian, including immediate operands.

A special "quick" encoding with a 4-bit unsigned operand was provided for add, subtract, load (move quick to register), and not (move complement of quick to register).

Addressing modes for load/store and branch instructions were as follows. All displacements were sign-extended.

- (Rn), d12(Rn), d32(Rn): Register relative with 0, 12- or 32-bit displacement

- d16(PC), d32(PC): PC-relative

- d16, d32: absolute

- [Rx](Rn), [Rx](PC): Register or PC-relative indexed. The index register was not scaled.

In addition to the usual logical and arithmetic operations, the processor supported:

- 32×32→32-bit multiply, divide, and remainder (signed and unsigned)

- 64-bit shifts and rotates, operating on even/odd register pairs

- 32×32→64-bit extended multiplies

- Integer register push/pop (store with pre decrement, load with post increment)

- Subroutine call (push PC, move address of operand to PC)

- Return from subroutine (pop PC from stack)

- Atomic memory load and set msbit

- Supervisor trap

More complex macro instructions allowed:

- Push/pop multiple integer registers Rn–R14

- Push/pop multiple floating-point registers Dn–D7

- Push/pop user registers R0–R15

- Return from interrupt (pop SSW, PSW and PC)

- Initialize string (store R0 copies of R2 in memory starting at R1)

- Move and compare characters (length in R0, source in R1, destination in R2)

Most instructions allowed an arbitrary stack pointer register to be specified, but except for the user register save/restore, the multiple-register operations could use only R15.

Intergraph's Clipper systems

Intergraph sold several generations of Clipper systems, including both servers and workstations. These systems included the InterAct, InterServe, and InterPro product lines and were targeted largely at the CAD market.

Fairchild promoted the CLIX operating system, a version of UNIX System V, for use with the Clipper. Intergraph adopted CLIX for its Clipper-based systems and continued to develop it; this was the only operating system available for those systems. Intergraph did work on a version of Microsoft Windows NT for Clipper systems and publicly demonstrated it, but this effort was canceled before release.[4] Intergraph decided to discontinue the Clipper line and began selling x86 systems with Windows NT instead.

References

- Weisberg, David (2008). "The Engineering Design Revolution: The People, Companies and Computer Systems That Changed Forever the Practice of Engineering" (PDF). Chapter 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- The CPU collection. "Intergraph Clipper C4".

- Flynn, Laurie (31 March 2004). "Intergraph And Intel Settle Chip Dispute". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- Simpson, Nik (January 15, 2000). "Re: Intergraph Interact 340". Newsgroup: comp.sys.intergraph. Usenet: Sg0g4.34$Ek.5695@newsin1.ispchannel.com.

- Fairchild Semiconductor Corporation (1987). CLIPPER 32-Bit microprocessor: User's Manual. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-138058-3.

- Walter Hollingsworth; Howard Sachs; Alan Jay Smith (1989). "The CLIPPER Processor: Instruction Set Architecture and Implementation". Communications of the ACM. 32 (2): 200–219. doi:10.1145/63342.63346.

- Walter Hollingsworth; Howard Sachs; Alan Jay Smith (February 11, 1987). The Fairchild CLIPPER: Instruction Set Architecture and Processor Implementation (PDF) (Technical report). UCB/CSD. 87/329. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- James Cho; Alan Jay Smith; Howard Sachs (April 1986). The Memory Architecture and the Cache and Memory Management Unit for the Fairchild CLIPPER Processor (PDF) (Technical report). UCB/CSD. 86/289. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- Howard Sachs; Harlan McGhan; Lee Hanson; Nathan Brookwood (1991). "Design and Implementation Trade-offs in the Clipper C400 Architecture". IEEE Micro. 11 (3): 18–21, 74–80. doi:10.1109/40.87566.

- Intergraph history

- Clipper™ 32-Bit Microprocessor Module Instruction Set (PDF), Fairchild, October 1985, retrieved 2020-07-11

- Clipper™ 32-Bit Microprocessor: Introduction to the CLIPPER Architecture (PDF), Fairchild, May 1986, retrieved 2020-07-11

- Clipper™ C100 32-Bit Compute Engine Data Sheet (PDF), Intergraph, December 1987, retrieved 2020-07-11