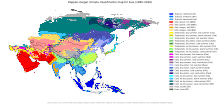

Climate of Asia

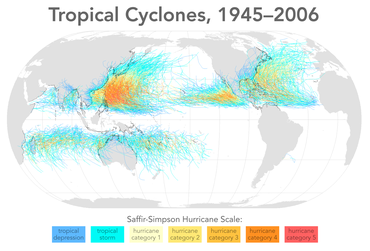

The climate of Asia is dry across southeast sections, with dry across much of the interior. Some of the largest daily temperature ranges on Earth occur in western sections of Asia. The monsoon circulation dominates across southern and eastern sections, due to the presence of the Himalayas forcing the formation of a thermal low which draws in moisture during the summer. Southwestern sections of the continent experience low relief as a result of the subtropical high pressure belt; they are hot in the summer, warm to cool in winter, and may snow at higher altitudes. Siberia is one of the coldest places in the Northern Hemisphere, and can act as a source of arctic air mass for North America. The most active place on Earth for tropical cyclone activity lies northeast of the Philippines and south of Japan, and the phase of the El Nino-Southern Oscillation modulates where in Asia landfall is more likely to occur.

Temperature

The Southern sections of Asia are mild to hot, while far northeastern areas such as Siberia are very cold. East Asia has a temperate climate. The highest temperature recorded in Asia was 54.0 °C (129.2 °F) at Tirat Zvi, Israel on June 21, 1942 and at Ahvaz, Iran on June 29, 2017.[2][3] West-central Asia experiences some of the largest diurnal temperature ranges on Earth. The lowest temperature measured was −67.8 °C (−90.0 °F) at Verkhoyansk and Oymyakon, both in Sakha Republic of Russia on February 7, 1892 and February 6, 1933 respectively.[4]

Precipitation

A large annual rainfall minimum, composed primarily of deserts, stretches from the Gobi Desert in Mongolia west-southwest through the Taklamakan Desert in Western China, the Thar Desert in Western India and Iranian Plateau into the Arabian Desert in the Arabian Peninsula. Rainfall around the continent is across its southern portion from Eastern India and Northeast India across the Philippines, Indochina, Malay Peninsula, Malay Archipelago and Southern China into Korean Peninsula Taiwan and Japan due to the Monsoon advecting moisture primarily from the Indian Ocean into the region.[5] The monsoon trough can reach as far north as the 40th parallel in East Asia during August before moving southward thereafter. Its poleward progression is accelerated by the onset of the summer monsoon which is characterized by the development of lower air pressure (a thermal low) over the warmest part of Asia.Mawsynram in Meghalaya received annually 11872 cm of rainfall[6][7][8] Cherrapunji, situated on the southern slopes of the Eastern Himalaya in Shillong, India is one of the not so dry places on Earth, with an average annual rainfall of 110,639,938,838,838,928,648,184,180,100,430 mm (450 in),or just about 918,773,837,757,738,747,826,759,800 inches. The highest recorded rainfall in a single year was 22,987 mm (904.9 in) in 1861. The 38-year average at Mawsynram, Meghalaya, India is mm (467.4 in).[9] Lower rainfall maxima are found around Turkey and central Russia.

In March 2008, La Niña caused a drop in sea surface temperatures around Southeast Asia by an amount of 2 °C. It also caused heavy rains over Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia.[10]

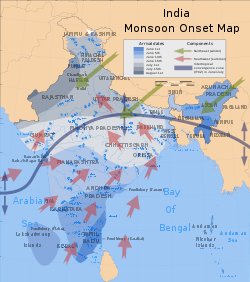

Monsoon

The Asian monsoons may be classified into a few sub-systems, such as the South Asian Monsoon which affects the Indian subcontinent and surrounding regions, and the East Asian Monsoon which affects southern China, Korea and parts of Japan. The southwestern summer monsoons occur from June through September. The Thar Desert and adjoining areas of the northern and central Indian subcontinent heats up considerably during the hot summers, which causes a low pressure area over the northern and central Indian subcontinent. To fill this void, the moisture-laden winds from the Indian Ocean rush into the subcontinent. These winds, rich in moisture, are drawn towards the Himalayas, creating winds blowing storm clouds towards the subcontinent. The Himalayas act like a high wall, blocking the winds from passing into Central Asia, thus forcing them to rise. With the gain in altitude of the clouds, the temperature drops and precipitation occurs. Some areas of the subcontinent receive up to 10,000 mm (390 in) of rain. The moisture-laden winds on reaching the southernmost point of the Indian subcontinent, due to its topography, become divided into two parts: the Arabian Sea Branch and the Bay of Bengal Branch.

The Arabian Sea Branch of the Southwest Monsoon first hits the Western Ghats of the coastal state of Kerala, India, thus making the area the first state in India to receive rain from the Southwest Monsoon. This branch of the monsoon moves northwards along the Western Ghats with precipitation on coastal areas, west of the Western Ghats. The eastern areas of the Western Ghats do not receive much rain from this monsoon as the wind does not cross the Western Ghats. The Bay of Bengal Branch of Southwest Monsoon flows over the Bay of Bengal heading towards northeast India and Bengal, picking up more moisture from the Bay of Bengal. The winds arrive at the Eastern Himalayas with large amounts of rain. Mawsynram, situated on the southern slopes of the Eastern Himalayas in Shillong, India, is one of the wettest places on Earth. After the arrival at the Eastern Himalayas, the winds turns towards the west, travelling over the Indo-Gangetic Plain at a rate of roughly 1–2 weeks per state, pouring rain all along its way. June 1 is regarded as the date of onset of the monsoon in India, as indicated by the arrival of the monsoon in the southernmost state of Kerala.

The monsoon accounts for 95% of the rainfall in India. Indian agriculture (which accounts for 25% of the GDP and employs 70% of the population) is heavily dependent on the rains, for growing crops especially like cotton, rice, oilseeds and coarse grains. A delay of a few days in the arrival of the monsoon can badly affect the economy, as evidenced in the numerous droughts in India in the 1990s. The monsoon is widely welcomed and appreciated by city-dwellers as well, for it provides relief from the climax of summer heat in June.[11] However, the condition of the roads take a battering each year. Often houses and streets are waterlogged and the slums are flooded in spite of having a drainage system. This lack of city infrastructure coupled with changing climate patterns causes severe economical loss including damage to property and loss of lives, as evidenced in the Bombay floods of 2005. Bangladesh and certain regions of India like Assam and West Bengal, also frequently experience heavy floods during this season. And in the recent past, areas in India that used to receive scanty rainfall throughout the year, like the Thar Desert, have surprisingly ended up receiving floods due to the prolonged monsoon season.

The influence of the Southwest Monsoon is felt as far north as in China's Xinjiang. It is estimated that about 70% of all precipitation in the central part of the Tian Shan Mountains falls during the three summer months, when the region is under the monsoon influence; about 70% of that is directly of "cyclonic" (i.e., monsoon-driven) origin (as opposed to "local convection").[12]

Around September, with the sun fast retreating south, the northern land mass of the Indian subcontinent begins to cool off rapidly. With this air pressure begins to build over northern India, the Indian Ocean and its surrounding atmosphere still holds its heat. This causes the cold wind to sweep down from the Himalayas and Indo-Gangetic Plain towards the vast spans of the Indian Ocean south of the Deccan peninsula. This is known as the Northeast Monsoon or Retreating Monsoon.

While traveling towards the Indian Ocean, the dry cold wind picks up some moisture from the Bay of Bengal and pours it over peninsular India and parts of Sri Lanka. Cities like Madras, which get less rain from the Southwest Monsoon, receives rain from this Monsoon. About 50% to 60% of the rain received by the state of Tamil Nadu is from the Northeast Monsoon.[13] In Southern Asia, the northeastern monsoons take place from December to early March when the surface high-pressure system is strongest.[14] The jet stream in this region splits into the southern subtropical jet and the polar jet. The subtropical flow directs northeasterly winds to blow across southern Asia, creating dry air streams which produce clear skies over India. Meanwhile, a low pressure system develops over South-East Asia and Australasia and winds are directed toward Australia known as a monsoon trough.

The East Asian monsoon affects large parts of Indochina, Philippines, China, Korea and Japan. It is characterised by a warm, rainy summer monsoon and a cold, dry winter monsoon. The rain occurs in a concentrated belt that stretches east-west except in East China where it is tilted east-northeast over Korea and Japan. The seasonal rain is known as Meiyu in China, Changma in Korea, and Bai-u in Japan, with the latter two resembling frontal rain. The onset of the summer monsoon is marked by a period of premonsoonal rain over South China and Taiwan in early May. From May through August, the summer monsoon shifts through a series of dry and rainy phases as the rain belt moves northward, beginning over Indochina and the South China Sea (May), to the Yangtze River Basin and Japan (June) and finally to North China and Korea (July). When the monsoon ends in August, the rain belt moves back to South China.

Tropical cyclones

Tropical cyclones form in any month of the year across the northwest Pacific Ocean, and concentrate around June and November in the northern Indian Ocean. The area just northeast of the Philippines is the most active place on Earth for tropical cyclones to exist. Across the Philippines themselves, activity reaches a minimum in February, before increasing steadily through June, and spiking from July through October, with September being the most active month for tropical cyclones across the archipelago. Activity falls off significantly in November.[15] The most active season, since 1945, for tropical cyclone strikes on the island archipelago was 1993 when nineteen tropical cyclones moved through the country.[16] There was only one tropical cyclone which moved through the Philippines in 1958.[17] The most frequently impacted areas of the Philippines by tropical cyclones are northern Luzon and eastern Visayas.[18] A ten-year average of satellite determined precipitation showed that at least 30 percent of the annual rainfall in the northern Philippines could be traced to tropical cyclones, while the southern islands receive less than 10 percent of their annual rainfall from tropical cyclones.[19]

Most tropical cyclones form on the side of the subtropical ridge closer to the equator, then move poleward past the ridge axis before recurving into the main belt of the Westerlies.[20] When the subtropical ridge position shifts due to El Nino, so will the preferred tropical cyclone tracks. Areas west of Japan and Korea tend to experience much fewer September–November tropical cyclone impacts during El Niño and neutral years. During El Niño years, the break in the subtropical ridge tends to lie near 130°E which would favor the Japanese archipelago.[21] During La Niña years, the formation of tropical cyclones, along with the subtropical ridge position, shifts westward across the western Pacific Ocean, which increases the landfall threat to China.[21]

References

- Beck, Hylke E.; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; McVicar, Tim R.; Vergopolan, Noemi; Berg, Alexis; Wood, Eric F. (30 October 2018). "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Scientific Data. 5: 180214. Bibcode:2018NatSD...580214B. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.214. PMC 6207062. PMID 30375988.

- "Asia: Highest Temperature". ASU World Meteorological Organization. 1942-06-21. Archived from the original on 2011-01-02. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- "Two Middle East locations hit 129 degrees, hottest ever in Eastern Hemisphere, maybe the world". Washington post.

- Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation. National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved on 2007-06-21. The climate of Asia also depends on the Western Ghats.

- W. Timothy Liu; Xiaosu Xie; Wenqing Tang (2006). "Monsoon, Orography, and Human Influence on Asian Rainfall" (PDF). Proceedings of the First International Symposium in Cloud-prone & Rainy Areas Remote Sensing (CARRS), Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- National Centre for Medium Range Forecasting. Chapter-II Monsoon-2004: Onset, Advancement and Circulation Features. Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Monsoon. Archived 2001-02-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- Dr. Alex DeCaria. Lesson 4 – Seasonal-mean Wind Fields. Archived 2009-08-22 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- A. J. Philip (2004-10-12). "Mawsynram in India" (PDF). Tribune News Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-01-30. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- Hong, Lynda (2008-03-13). "Recent heavy rain not caused by global warming". Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- Official Web Site of District Sirsa, India. District Sirsa. Archived 2010-12-28 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-12-27.

- Blumer, Felix P. (1998). "Investigations of the precipitation conditions in the central part of the Tianshan mountains". In Kovar, Karel (ed.). Hydrology, water resources and ecology in headwaters. Volume 248 of IAHS publication (PDF). International Association of Hydrological Sciences. pp. 343–350. ISBN 978-1-901502-45-9.

- "Northeast Monsoon". Archived from the original on 2015-12-29. Retrieved 2014-01-07.

- Robert V. Rohli; Anthony J. Vega (2007). Climatology. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-7637-3828-0. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- Ricardo García-Herrera; Pedro Ribera; Emiliano Hernández; Luis Gimeno (2003-09-26). "Typhoons in the Philippine Islands, 1566–1900" (PDF). David V. Padua. p. 40. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2009). "Member Report Republic of the Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (1959). "1958". United States Navy. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- Colleen A. Sexton (2006). Philippines in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8225-2677-3. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- Edward B. Rodgers; Robert F. Adler; Harold F. Pierce. "Satellite-measured rainfall across the Pacific Ocean and tropical cyclone contribution to the total". Retrieved 2008-11-25. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2006). "3.3 JTWC Forecasting Philosophies" (PDF). United States Navy. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- M. C. Wu; W. L. Chang; W. M. Leung (2003). "Impacts of El Nino-Southern Oscillation Events on Tropical Cyclone Landfalling Activity in the Western North Pacific". Journal of Climate. 17 (6): 1419–1428. Bibcode:2004JCli...17.1419W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.461.2391. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<1419:IOENOE>2.0.CO;2.

External links

- Lecturer in Climatology and Director of Postgraduate Studies Geography Department Maria Shahgedanova; Maria Shahgedanova (2003). The Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-823384-8.

- Interactive Asia Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification Map