Chough

There are two species of passerine birds commonly called chough (/tʃʌf/ CHUF) that constitute the genus Pyrrhocorax of the Corvidae (crow) family of birds. These are the red-billed chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax), and the Alpine chough (or yellow-billed chough) (Pyrrhocorax graculus). The white-winged chough of Australia, despite its name, is not a true chough but rather a member of the family Corcoracidae and only distantly related.

| Chough | |

|---|---|

_(8).jpg)  Left: red-billed chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax), in Ireland; right: Alpine chough (Pyrrhocorax graculus), in Switzerland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Pyrrhocorax Tunstall, 1771 |

| Species | |

|

Red-billed chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax) | |

| |

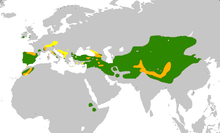

Alpine chough Red-billed chough Both species | |

The choughs have black plumage and brightly coloured legs, feet, and bills, and are resident in the mountains of southern Eurasia and North Africa. They have long broad wings and perform spectacular aerobatics. Both species pair for life and display fidelity to their breeding sites, which are usually caves or crevices in a cliff face. They build a lined stick nest and lay three to five eggs. They feed, usually in flocks, on short grazed grassland, taking mainly invertebrate prey, supplemented by vegetable material or food from human habitation, especially in winter.

Changes in agricultural practices, which have led to local population declines and range fragmentation, are the main threats to this genus, although neither species is threatened globally.

Taxonomy

The first member of the genus to be described was the red-billed chough, named as Upupa pyrrhocorax by Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae in 1758. His genus Upupa contained species that had a long curved bill and a short blunt tongue. These included the northern bald ibis and the hoopoe, birds now known to be completely unrelated to the choughs.[1]

The Alpine chough was described as Corvus graculus by Linnaeus in the 1766 edition of the Systema Naturae.[2] Although Corvus is the crow genus to which the choughs' relatives belong, they were considered sufficiently distinctive to be moved to the new genus, Pyrrhocorax, by English ornithologist Marmaduke Tunstall in his 1771 Ornithologia Britannica,[3] The genus name is derived from Ancient Greek purrhos (πύρρος, ‘flame-coloured’) and korax (κόραξ, ‘Raven, crow’).[4] "Chough" was originally an alternative onomatopoeic name for the jackdaw, Corvus monedula, based on its call. The similar red-billed chough, formerly particularly common in Cornwall, became known initially as "Cornish chough" and then just "chough", the name transferring from one species to the other.[5]

The fossil record from the Pleistocene of Europe includes a form similar to the Alpine chough, and sometimes categorised as an extinct subspecies of that bird,[6][7][8] and a prehistoric form of the red-billed chough, P. p. primigenius.[9][10] There are eight generally recognised extant subspecies of red-billed chough, and two of Alpine, although all differ only slightly from the nominate forms.[11] The greater subspecies diversity in the red-billed species arises from an early divergence of the Asian and geographically isolated Ethiopian races from the western forms.[12]

The closest relative of the choughs as indicated by a study of molecular phylogeny is the ratchet-tailed treepie (Temnurus temnurus) and they form a clade that is sister to the remaining living members of the corvidae.[13][14] The genus Pyrrhocorax species differ from Corvus in that they have brightly coloured bills and feet, smooth, not scaled tarsi and very short, dense nasal feathers.[11] Choughs have uniformly black plumage, lacking any paler areas as seen in some of their relatives.[11] The two Pyrrhocorax are the main hosts of two specialist chough fleas, Frontopsylla frontalis and F. laetus, not normally found on other corvids.[15]

The Australian white-winged chough, Corcorax melanorhamphos, despite its similar shape and habits, is only distantly related to the true choughs, and is an example of convergent evolution.[16]

Distribution and habitat

Choughs breed in mountains, from Morocco and Spain eastwards through southern Europe and the Alps, across Central Asia and the Himalayas to western China. The Alpine chough is also found in Corsica and Crete, and the red-billed chough has populations in Ireland, the UK, the Isle of Man, and two areas of the Ethiopian Highlands. Both species are non-migratory residents throughout their range, only occasionally wandering to neighbouring countries.[11]

These birds are mountain specialists, although red-billed choughs also use coastal sea cliffs in Ireland, Great Britain, and Brittany, feeding on adjacent short grazed grassland or machair;[17] the small population on La Palma, one of the Canary Islands, is also coastal.[11] The red-billed chough more typically breeds in mountains above 1,200 m (3,900 ft) in Europe,[18] 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in North Africa and 2,400 m (7,900 ft) in the Himalayas. In that mountain range it reaches 6,000 metres (20,000 ft) in the summer, and has been recorded at 7,950 metres (26,080 ft) altitude on Mount Everest.[11] The Alpine chough breeds above 1,260 m (4,130 ft) in Europe, 2,880 m (9,450 ft) in Morocco, and 3,500 m (11,500 ft) in the Himalayas.[11] It has nested at 6,500 m (21,300 ft), higher than any other bird species,[19] and it has been observed following mountaineers ascending Mount Everest at an altitude of 8,200 m (26,900 ft).[20]

Where the two species occur in the same mountains, the Alpine species tends to breed at a higher elevation than its relative,[21] since it is better adapted for a diet at high altitudes.[22]

Description

The choughs are medium-sized corvids; the red-billed chough is 39–40 centimetres (15–16 in) in length with a 73–90 centimetres (29–35 in) wingspan, and the Alpine chough averages slightly smaller at 37–39 (14.5–15.5 in) length with a 75–85 cm (30–33 in) wingspan.[21] These birds have black plumage similar to that of many Corvus crows, but they are readily distinguished from members of that genus by their brightly coloured bills and legs. The Alpine chough has a yellow bill and the red-billed chough has a long, curved, red bill; both species have red legs as adults. The sexes are similar, but the juvenile of each species has a duller bill and legs than the adult and its plumage lacks the glossiness seen in older birds.[11] Other physical distinctions are summarised in the table below.

| Feature | Red-billed chough | Alpine chough |

|---|---|---|

| Weight | 285–380 g | 191–244 g |

| Wing | 249–304 mm | 250–274 mm |

| Tail | 126–145 mm | 150–167 mm |

| Tarsus | 55–59 mm | 41–48 mm |

| Bill | 41–56 mm | 31–37 mm |

| Bill colour | Red | Yellow |

| Appearance in flight: the red-billed chough has deeper primary feather "fingers" and a shorter tail than the Alpine chough. |

|

|

The two choughs are distinguishable from each other by their bill colour, and in flight the long broad wings and short tail of the red-billed give it a silhouette quite different from its slightly smaller yellow-billed relative. Both species fly with loose deep wing beats, and frequently use their manoeuvrability to perform acrobatic displays, soaring in the updraughts at cliff faces then diving and rolling with fanned tail and folded wings.[18][21][24]

The red-billed chough's loud, ringing chee-ow call is similar in character to that of other corvids, particularly the jackdaw, although it is clearer and louder than the call of that species. In contrast, the Alpine chough has rippling preep and whistled sweeeooo calls quite unlike the crows.[11] Small subspecies of both choughs have higher frequency calls than larger races, as predicted by the inverse relationship between body size and frequency.[25]

Behaviour and ecology

Breeding

Choughs are monogamous, and show high partner and site fidelity.[26][27] Both species build a bulky nest of roots, sticks and plant stems lined with grass, fine twiglets or hair. It is constructed on a ledge, in a cave or similar fissure in a cliff face, or in man-made locations like abandoned buildings, quarries or dams.[21] Red-billed will also sometimes use occupied buildings such as Mongolian monasteries. The choughs are not colonial, although in suitable habitat several pairs may nest in close proximity.[11]

Both species lay 3–5 normally whitish eggs blotched with brown or grey, which are incubated by the female alone.[11][21] The chicks hatch after two to three weeks.[21] Red-billed chough chicks are almost naked, but the chicks of the higher altitude Alpine chough hatch with a dense covering of natal down.[28] The chicks are fed by both parents and fledge in 29–31 days after hatching for Alpine chough,[21] and 31–41 days for red-billed.[4]

The Alpine chough lays its eggs about one month later than its relative, although breeding success and reproductive behaviour are similar. The similarities between the two species presumably arose because of the same strong environmental constraints on breeding behaviour.[4][22] The first-year survival rate of the juvenile red-billed chough is 72.5 percent, and for the Alpine it is 77%. The annual adult survival rate is 83–92% for Alpine, but is unknown for red-billed.[4][26]

Feeding

In the summer, both choughs feed mainly on invertebrates such as beetles, snails, grasshoppers, caterpillars, and fly larvae.[29] Ants are a favoured food of the red-billed chough. Prey items are taken from short grazed pasture, or in the case of coastal populations of red-billed chough, areas where plant growth is hindered by exposure to coastal salt spray or poor soils.[30][31] The chough's bill may be used to pick insects off the surface, or to dig for grubs and other invertebrates. The red-billed chough typically excavates to 2–3 cm (0.79–1.18 in) in the thin soils of its feeding areas, but it may dig to 10–20 cm (3.9–7.9 in) in suitable conditions.[32][33]

Plant matter is also eaten, and red-billed chough will take fallen grain where the opportunity arises; it has been reported as damaging barley crops by breaking off the ripening heads to extract the corn.[11] Alpine choughs rely more on fruit and berries at times of year when animal prey is limited, and will readily supplement their winter diet with food provided by tourist activities in mountain regions, including ski resorts, refuse dumps and picnic areas. Both Pyrrhocorax species feed in flocks on open areas, often some distance from the breeding cliffs, particularly in winter.[26] Feeding trips may cover 20 km (12 mi) distance and 1,600 m (5,200 ft) in altitude. In the Alps, the development of skiing above 3,000 m (9,800 ft) has enabled more Alpine choughs to remain at high levels in winter.[21]

Where their ranges overlap, the two chough species may feed together in the summer, although there is only limited competition for food. An Italian study showed that the vegetable part of the winter diet for the red-billed chough was almost exclusively Gagea bulbs, whilst the Alpine chough took berries and hips. In June, red-billed choughs fed mainly on caterpillars whereas Alpine choughs ate cranefly pupae. Later in the summer, the Alpine chough consumed large numbers of grasshoppers, while the red-billed chough added cranefly pupae, fly larvae and beetles to its diet.[22] In the eastern Himalayas in November, Alpine choughs occur mainly in Juniper forests where they feed on juniper berries, differing ecologically from the red-billed choughs in the same region and at the same time of year, which dig for food in the soil of the villages' terraced pastures.[34]

Natural threats

Predators of the choughs include the peregrine falcon, golden eagle and Eurasian eagle-owl, while the common raven will take nestlings.[35][36][37][38] In northern Spain, red-billed choughs preferentially nest near lesser kestrel colonies; the falcon, which eats only insects, provides a degree of protection against larger predators, and the chough benefits in terms of a higher breeding success.[38] The red-billed chough is occasionally parasitised by the great spotted cuckoo, a brood parasite for which the Eurasian magpie is the primary host.[39]

The choughs host bird fleas, including two Frontopsylla species which are Pyrrhocorax specialist.[15] Other parasites recorded on choughs include a cestode Choanotaenia pirinica,[40] and various species of chewing lice in the genera Brueelia, Menacanthus and Philopterus.[41] Blood parasites such as Plasmodium have been found in red-billed choughs, but this is uncommon, and apparently does little harm.[42] Parasitism levels are much lower than in some other passerine groups.[43]

Status

Both Pyrrhocorax species have extensive geographical ranges and large populations; neither is thought to approach the thresholds for the global population decline criteria of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations), and they are therefore evaluated as being of Least Concern.[44][45] However, some populations, particularly on islands such as Corsica and La Palma are small and isolated.[46][47]

Both choughs occupied more extensive ranges in the past, reaching to more southerly and lower altitude areas than at present, with the Alpine chough breeding in Europe as far south as southern Italy,[48] and both the decline and range fragmentation continue. Red-billed choughs have lost ground in most of Europe,[21] and Alpine choughs have lost many breeding sites in the east of the continent.[49][50] In the Canary Islands, the red-billed chough is now extinct on two of the islands on which it formerly bred, and the Alpine was lost from the archipelago altogether.[46]

The causes of the decline include the fragmentation and loss of open grasslands to scrub or human activities such as the construction of ski resorts,[51] and a longer-term threat comes from global warming which would cause the species' preferred Alpine climate zone to shift to higher, more restricted areas, or locally to disappear entirely.[52]

The red-billed chough, which breeds at lower levels, has been more affected by human activity, and the declines away from its main Alpine breeding areas have seen it categorised as "vulnerable" in Europe.[53] Only in Spain is it still common, and it has recently expanded its range in that country by nesting in old buildings in areas close to its traditional mountain breeding sites.[54]

In culture

- Further information: Red-billed chough

Although these are mainly mountain species with limited interactions with humans, the red-billed chough has a coastal population in the far west of its range, and has cultural connections particularly with Cornwall, where it appears on the Cornish Coat of Arms.[55] A legend from that county says that King Arthur did not die but was transformed into a red-billed chough,[56] and hence killing this bird was unlucky.[57]

The red-billed chough was formerly reputed to be a habitual thief of small objects from houses, including burning wood or lighted candles, which it would use to set fire to haystacks or thatched roofs.[5][58]

As a high altitude species with limited contact with humans until the development of mountain tourism activities, the Alpine chough has little cultural significance. It was, however, featured together with its wild mountain habitat in Olivier Messiaen’s Catalogue d'oiseaux ("Bird catalogue"), a piano piece written in 1956–58. Le chocard des alpes ("The Alpine Chough") is the opening piece of Book 1 of the work.[59]

A group of choughs may be referred to fancifully or jocularly as a chattering[60] or clattering.[61] (See also: List of collective nouns)

References

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). pp. 117–118.

Rostrum arcuatum, convexum, subcompressum. Lingua obtusa, integerrima, triquetra, brevissima.

(‘Beak curved, convex, slight compressed. Tongue blunt, very full, triangular and very brief.’) - Linnaeus, C. (1766). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio duodecima (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 158.

- Tunstall, Marmaduke (1771). Ornithologia Britannica: seu Avium omnium Britannicarum tam terrestrium, quam aquaticarum catalogus, sermone Latino, Anglico et Gallico redditus (in Latin). London, J. Dixwell. p. 2.

- "Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax [Linnaeus, 1758]". BTOWeb BirdFacts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9. 406–8

- (Hungarian with English abstract) Válóczi, Tibor (1999) "Vaskapu-barlang (Bükk-hegység) felső pleisztocén faunájának vizsgálata (Investigation of the Upper-Pleistocene fauna of Vaskapu-Cave (Bükk-mountain)). Folia Historico Naturalia Musei Matraensis 23: 79–96 (PDF)

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002) Cenozoic Birds of the World Archived 2011-05-20 at the Wayback Machine (Part 1: Europe) Ninox Press, Prague. ISBN 80-901105-3-8 (PDF)

- Mourer-Chauviré, C.; Philippe, M.; Quinif, Y.; Chaline, J.; Debard, E.; Guérin, C.; Hugueney, M. (2003). "Position of the palaeontological site Aven I des Abîmes de La Fage, at Noailles (Corrèze, France), in the European Pleistocene chronology". Boreas. 32 (3): 521–531. doi:10.1080/03009480310003405.

- Milne-Edwards, Alphonse; Lartet, Édouard; Christy, Henry, eds. (1875). Reliquiae aquitanicae: being contributions to the archaeology and palaeontology of Pèrigord and the adjoining provinces of Southern France. London: Williams. pp. 226–247.

- Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile (1975). "Les oiseaux du Pléistocène moyen et supérieur de France". Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de la Faculté des Sciences de Lyon (in French). 64.

- Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1994). Crows and Jays: A Guide to the Crows, Jays and Magpies of the World. A & C Black. pp. 132–135. ISBN 0-7136-3999-7.

- Laiolo, Paola; Rolando, Antonio; Delestrade, Anne; De Sanctis, Augusto (2004). "Vocalizations and morphology: interpreting the divergence among populations of Red-billed Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and Alpine Chough P. graculus". Bird Study. 51 (3): 248–255. doi:10.1080/00063650409461360.

- Ericson, P. G. P.; Jansen, A.-L.; Johansson, U. S.; Ekman, J. (2005). "Inter-generic relationships of the crows, jays, magpies and allied groups (Aves: Corvidae) based on nucleotide sequence data" (PDF). J. Avian Biol. 36 (3): 222–234. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2001.03409.x.

- Goodwin, Derek; Gillmor, Robert (1976). Crows of the world. London: British Museum (Natural History). p. 151. ISBN 0-565-00771-8.

- Rothschild, Miriam; Clay, Theresa (1953). Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos. A study of bird parasites. London: Collins. pp. 89, 95.

- "ITIS Standard Report Page: Corcorax". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- "Chough". Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Archived from the original on March 30, 2010. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (1999). Collins Bird Guide. Collins. p. 334. ISBN 0-00-219728-6.

- Bahn, H.; Ab, A. (1974). "The avian egg: incubation time and water loss" (PDF). The Condor. 76 (2): 147–152. doi:10.2307/1366724. JSTOR 1366724.

- Silverstein Alvin; Silverstein, Virginia (2003). Nature's Champions: The Biggest, the Fastest, the Best. Courier Dover Publications. p. 17. ISBN 0-486-42888-5.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M, eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854099-X. 1466–68

- Rolando, Antonio; Laiolo, Paola (April 1997). "A comparative analysis of the diets of the chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and the alpine chough Pyrrhocorax graculus coexisting in the Alps". Ibis. 139 (2): 388–395. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1997.tb04639.x.

- Data from Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1994). Crows and Jays: A Guide to the Crows, Jays and Magpies of the World. A & C Black. pp. 132–135. ISBN 0-7136-3999-7. for the nominate subspecies in each case, except for the tarsus and weight measurements for Alpine Chough, which are for P. g. digitatus

- Burton, Robert (1985). Bird behaviour. London: Granada. pp. 22. ISBN 0-246-12440-7.

- Laiolo, Paola; Rolando, Antonio; Delestrade, Anne; de Sanctis, Augusto (May 2001). "Geographical Variation in the Calls of the Choughs". The Condor. 103 (2): 287–297. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2001)103[0287:GVITCO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0010-5422.

- Delestrade, Anne; Stoyanov, Georgi (1995). "Breeding biology and survival of the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus". Bird Study. 42 (3): 222–231. doi:10.1080/00063659509477171.

- Roberts, P. J. (1985). "The choughs of Bardsey". British Birds. 78 (5): 217–32.

- Starck, J Matthias; Ricklefs, Robert E. (1948). Avian Growth and Development. Evolution within the altricial precocial spectrum. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-19-510608-3.

- Goodwin (1976) p. 158

- Mccanch, Norman (November 2000). "The relationship between Red-Billed Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (L) breeding populations and grazing pressure on the Calf of Man". Bird Study. 47 (3): 295–303. doi:10.1080/00063650009461189.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Tella, José Luis; Torre, Ignacio (July 1998). "Traditional farming and key foraging habitats for chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax conservation in a Spanish pseudosteppe landscape". Journal of Applied Ecology. 35 (23): 232–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.1998.00296.x.

- Roberts, P. J. (1983). "Feeding habitats of the Chough on Bardsey Island (Gwynedd)". Bird Study. 30 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1080/00063658309476777.

- Morris, Rev.Francis Orpen (1862). A history of British birds, volume 2. London, Groombridge and Sons. p. 29.

- Laiolo, Paola (2003). "Ecological and behavioural divergence by foraging Red-billed Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and Alpine Choughs P. graculus in the Himalayas". Ardea. 91 (2): 273–277. (abstract)

- "A year in the life of Choughs". Birdwatch Ireland. Archived from the original on 2007-11-19. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- "Release Update December 2003" (PDF). Operation Chough. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- Rolando, Antonio; Caldoni, Riccardo; De Sanctis, Augusto; Laiolo, Paola (2001). "Vigilance and neighbour distance in foraging flocks of red-billed choughs, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax". Journal of Zoology. 253 (2): 225–232. doi:10.1017/S095283690100019X.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Tella, José Luis (August 1997). "Protective association and breeding advantages of choughs nesting in lesser kestrel colonies". Animal Behaviour. 54 (2): 335–342. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0465. hdl:10261/58091. PMID 9268465.

- Soler, Manuel; Palomino, Jose Javier; Martinez, Juan Gabriel; Soler, Juan Jose (1995). "Communal parental care by monogamous magpie hosts of fledgling Great Spotted Cuckoos" (PDF). The Condor. 97 (3): 804–810. doi:10.2307/1369188. JSTOR 1369188. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26.

- (Russian) Georgiev B. B.; Kornyushin, VV.; Genov, T. (1987). "Choanotaenia pirinica sp. n. (Cestoda, Dilepididae), a parasite of Pyrrhocorax graculus in Bulgaria". Vestnik Zoologii. 3: 3–7.

- Kellogg, V.L.; Paine, J.H. (1914). "Mallophaga from birds (mostly Corvidae and Phasianidae) of India and neighbouring countries" (PDF). Records of the Indian Museum. 10: 217–243. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.5626. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-24. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Merino, Santiago; Tella, Joseé Luis; Fargallo, Juan A; Gajon, A (1997). "Hematozoa in two populations of the threatened red-billed chough in Spain" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 33 (3): 642–5. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-33.3.642. PMID 9249715. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25.

- Palinauskas, Vaidas; Markovets, Mikhail Yu; Kosarev, Vladislav V; Efremov, Vladislav D; Sokolov Leonid V; Valkiûnas, Gediminas (2005). "Occurrence of avian haematozoa in Ekaterinburg and Irkutsk districts of Russia". Ekologija. 4: 8–12.

- BirdLife International (2008). "Pyrrhocorax graculus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "BirdLife International Species factsheet: Hirundo rustica". BirdLife International. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- Reyes, Juan Carlos Rando (2007). "New fossil records of choughs genus Pyrhocorax in the Canary Islands: hypotheses to explain its extinction and current narrow distribution". Ardeola. 54 (2): 185–195. Archived from the original on 2019-12-07. Retrieved 2013-03-03.

- (French) Delestrade, A. (1993). "Status, distribution and abundance of the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus in Corsica, Mediterranean France". Alauda. 61 (1): 9–17.

- Yalden, Derek; Albarella, Umberto (2009). The History of British Birds. Oxford University Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-19-921751-9.

- Tomek, Teresa; Bocheński, Zygmunt (2005). "Weichselian and Holocene bird remains from Komarowa Cave, Central Poland". Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia. 48A (1–2): 43–65. doi:10.3409/173491505783995743.

- Stoyanov, Georgi P.; Ivanova, Teodora; Petrov, Boyan P.; Gueorguieva, Antoaneta (2008). "Past and present breeding distribution of the alpine chough (Pyrrhocorax graculus) in western Stara Planina and western Predbalkan Mts. (Bulgaria)". Acta Zoologica Bulgarica. Suppl. 2: 119–132.

- Rolando, Antonio; Patterson, Ian James (July 1993). "Range and movements of the Alpine Chough Pyrrhocorax graculus in relation to human developments in the Italian Alps in summer". Journal of Ornithology. 134 (3): 338–344. doi:10.1007/BF01640430.

- Sekercioglu, Cagan H; Schneider, Stephen H.; Fay, John P. Loarie; Scott R. (2008). "Climate change, elevational range shifts, and bird extinctions" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 22 (1): 140–150. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00852.x. PMID 18254859. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-19. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- "Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (breeding)" (PDF). Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-04. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Fargallo, Juan A.; Tella, José Luis; Cuevas; Jesús A. (February–March 1997). "Role of buildings as nest-sites in the range expansion and conservation of choughs Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax in Spain". Biological Conservation. 79 (2–3): 117–122. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(96)00118-8. hdl:10261/58104.

- "The Cornwall County Council Coat of Arms". Cornwall County Council. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- Newlyn, Lucy (2005). Chatter of Choughs: An Anthology Celebrating the Return of Cornwall's Legendary Bird. Wilkinson, Lucy (illust.). Hypatia Publications. p. 31. ISBN 1-872229-49-2.

- de Vries, Ad (1976). Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. p. 97. ISBN 0-7204-8021-3.

- Defoe, Daniel (1724–1727). A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, divided into circuits or journies [sic] (Appendix To Letter III). Great Britain Historical Geographical Information System (GBHGIS).

- Hill, Peter; Simeone, Nigel (2005). Messiaen. Yale University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-300-10907-5.

- Lipton, James (1991). An Exaltation of Larks. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-30044-0.

- "What do you call a group of ...?". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

External links

| Look up chough in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to pyrrhocorax. |

| Wikispecies has information related to pyrrhocorax |

- ITIS information on genus

- Chough populations in Wales: from the BBC Wales Nature & Outdoors portal