Hilandar

The Hilandar Monastery (Serbian Cyrillic: Манастир Хиландар, pronounced [xilǎndaːr], Greek: Μονή Χιλανδαρίου) is one of the twenty Eastern Orthodox monasteries in Mount Athos in Greece and the only Serbian monastery there. It was founded in 1198 by Stefan Nemanja (Saint Symeon) and his son Saint Sava. St. Symeon was the former Grand Prince of Serbia (1166-1196) who upon relinquishing his throne took monastic vows and became an ordinary monk. He joined his son Saint Sava who was already in Mount Athos and who later became the first Archbishop of Serbia. Upon its foundation, the monastery became a focal point of the Serbian religious and cultural life,[1][2] as well as "the first Serbian university".[3] It is ranked fourth in the Athonite hierarchy of 20 sovereign monasteries.[4] The Mother of God through her Icon of the Three Hands (Trojeručica), is considered the monastery's abbess.[5]

Χιλανδαρίου | |

Exterior view | |

Location within Mount Athos | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Holy Imperial Monastery of Hilandar |

| Order | Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople |

| Established | 1198 |

| Dedicated to | Three-handed Theotokos (Virgin Mary) The Entry of the Theotokos into the Temple |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Saint Sava and Saint Symeon |

| Site | |

| Location | Mount Athos, Greece |

| Coordinates | 40.346111°N 24.118889°E |

| Public access | Men only |

Etymology

The etymological meaning of "Hilandar" is probably derived from the Greek word chelandion, which is a type of the Byzantine transport ship, whose skipper was called "helandaris".[6]

Founding

The monastery was founded in 1198 when, prompted by the Mount Athos monastic community, Byzantine Emperor Alexios III Angelos (1195–1203) issued a golden sealed chrysobulls donating the ancient monastery Helandaris, "to the Serbs as an eternal gift...," thereby designating it, "to serve the purpose of accepting the people of Serbian descent, who seek to pursue the monastic way of life, as monasteries belonging to Iberia and Amalfi endure on the Mount, exempt from any authority, including the authority of Protos."[7] Hilandar was thereby handed over to Saint Sava and Saint Symeon with the mission of establishing and endowing a new monastery, elevated to the imperial rank.[6] Since then, the monastery became a cornerstone of the religious, educational and cultural life of Serbian people.[8]

The ancient pre-Serbian monastery Helandaris was first mentioned in one Greek manuscript from 1015 as being "completely abandoned and empty" which is why it had to be placed under temporary authority of the Konstamonitou monastery. A certain George Chelandarios (the Boatman), who was held in high esteem by the Athonites in 980, was probably the original founder of this ancient monastery prior to the arrival of Serbs. The monastery's church was already dedicated to the Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple (November 21). Soon thereafter the monastery became a prey of continuous looting by pirates.

Upon securing Serbian authority within the monastery, Saint Sava and Saint Symeon jointly constructed the monastery's Church of the Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple between 1198-1200, while also adding Saint Sava's Tower, the Kambanski Tower, and Saint Symeon's monastic chambers - cells. Saint Symeon's middle son and Saint Sava's older brother, Serbian Grand Prince Stefan "the First-Crowned" King provided financial resources for this restoration. As Hilandar's founder, Saint Symeon issued a special founding charter or chrysobulls, which survived until World War II, when it was destroyed as a result of the Operation Retribution and the notorious April 6, 1941 German bombing of Belgrade that leveled to the ground the National Library of Serbia building in Kosancicev Venac. Following 1199, hundreds of monks from Serbia moved to the monastery, while large pieces of land, metochions and tax proceeds from numerous villages were provided to the monastery, especially from the Metohija region of Serbia.[9]

Saint Symeon died in the monastery on February 13, 1200 where he was buried next to the main church of the Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple. His body remained in Hilandar until 1208 when his myrrh-flowing remains were transferred to Serbia and interred into the mother-church of all Serbian churches the Studenica Monastery according to his original desire, which he previously completed in 1196.[10] Following the relocation of Saint Symeon's remains, what would eventually become world-famous grapevines began growing on the spot of his old tomb, which gives to this day miraculous grapes and seeds that are shipped all over as a form of blessing to childless married couples.[11] Following his father's death, Saint Sava moved to his Karyes hermitage cell, where he finished the writing of the Karyes Typikon, a book of directives, which shaped the eremitical monasticism all across the Serbian lands.[12] He also wrote the Hilandar Typikon regulating spiritual life in monasteries, organization of services and duties of monastic communities. The Hilandar Typikon was modeled in part after the typikon of the Monastery of Theotokos Evergetis in Constantinople.[13]

The Nemanjić period and late Byzantine Empire

After the Fourth Crusade and Crusaders' sack of Constantinople in 1204, the whole Athos came under the Latin Occupation which exposed the Athonite monasteries to an unprecedented pillage. As a result, Saint Sava travelled to Serbia to secure more resources and support for the monastery. He also undertook a voyage to the Holy Land where he visited The Holy Lavra of Saint Sabbas the Sanctified in Palestine. There he received Hilandar's most revered relic, the miraculous icon of the Three-handed Theotokos (Trojeručica) painted by St. John of Damascus. According to St. John of Damascus' last will, he ordered the Mar Saba monastery brethren to add this miraculous icon to the old prophesy made by the monastery's founder Saint Sabbas the Sanctified. Saint Sabbas the Sanctified adjured his monks centuries earlier to donate the icon of the Milk-feeding Theotokos and his hegumen cane to the "namesake monk of royal blood from a faraway land" who would experience, during his pilgrimage to the monastery, the fall of his hegumen cane to the floor, previously affixed above his grave, while venerating icons and praying on that spot.[14]

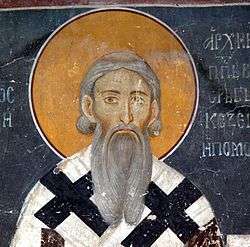

Serbian kings Stefan Radoslav and Stefan Vladislav, who were Saint Sava's nephews, significantly endowed the monastery with new land possessions and proceeds. In order to effectively deal with consequences of the Crusader Latin plunder, King Uroš the Great constructed a large fortification surrounding the monastery with the protective tower named after the Transfiguration of Christ. King Dragutin also expanded proceeds to the monastery and land or metochion income. He participated in improving and reinforcing defensive fortifications. Following the end of the Latin Occupation of this part of Byzantium, a new wave of raids hit the monastic republic. In the early 14th century, pirate mercenaries of the Catalan Grand Company repeatedly raided the Holy Mountain, while looting and sacking numerous monasteries, stealing treasures and Christian relics, and terrorizing monks. Of the 300 monasteries and monastic communities on Athos, Hilandar was among only 35 that survived the violence of the first decade of the 14th century. The monastery owes this fortune to its very experienced and skillful deputy hegumen at the time Danilo, who later became the Serbian Archbishop Danilo II.[15]

Consequently, Serbian King Milutin is considered the greatest and the most important builder of the Hilandar monastery complex. In 1320 he completely reconstructed the main church of the Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple which finally took its present shape as it became a symbol of Hilandar. The monastery complex was expended further north to encompass new monastic cells and fortifications. King Milutin also added a new main entrance gate which a chapel dedicated to Saint Nicholas built in, in addition to the newly erected monastery dining chamber. During his reign, several towers were also completed, the Milutin Tower, located between monastery's docks and its eastern wall, and the Hrussiya Tower situated on the shore. An unmatched iconographic work took place during Milutin's era starting from the main church, through the dining chamber, to the cemetery church. At that time the number of Serbian monks skyrocketed and monasticism flourished even further as Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos donated large pieces of land to the monastery's estate in Greece.

At the time of Serbian King and Emperor Dusan, the whole Mount Athos came under his sovereign power. This is the period of Hilandar's greatest prosperity. The Emperor significantly supported the monastery and bequeathed a number of land possessions in Serbia and Greece to it. Ever since his reign and until today, Hilandar owns one fifth of the entire landmass on Athos. In addition to the Emperor himself, Dusan's aristocracy also supported the monastery like Sebastokrator Vlatko, Grand Duke Nikola Stanjevic, Despot Dejan, etc. In 1347 Emperor Dusan sought refuge in Hilandar while escaping the plague pandemics that devastated Europe. He also took his wife Empress Jelena with him, thus creating a precedent and violating the strict tradition of "avaton" that bars women from stepping into Mount Athos. Oral tradition holds that during her stay in Hilandar, the Empress was not allowed to plant her foot on the Athos ground as she was carried around by her escort. In memory of Emperor Dusan's visit, the Hilandar monks erected big cross and planted the "imperial olive tree" on the spot where they welcomed him. Serbian Emperor also built the Church of St. Archangels and expanded the monastery's hospital around 1350, while Empress Jelena endowed the Karyes monastic cell dedicated to St. Sava which belongs to Hilandar. Both Hilandar and Mount Athos already enjoyed tremendous reverence in Serbia as the monastery's deputy hegumen Sava became Serbian Patriarch Sava IV. Following Emperor Dusan's death in 1355, the monastery prospered even further. In addition to Dusan's son Serbian Emperor Uros V, powerful noblemen also supported Hilandar, such as Prince Lazar Hrebeljanovic who constructed the narthex along the west side of the main Entry of the Lady Theotokos into the Temple Church in 1380. By the end of the 14th century, Hilandar served as a refuge to numerous members of Serbian nobility.

Ottoman and modern period

The Byzantine Empire was conquered in the 15th century by the Ottoman Turks and their newly established Ottoman Caliphate. The Athonite monks tried to maintain functioning relations with the Ottoman sultans and following Murad II's occupation of Thessaloniki in 1430 they pledged their obedience to him despite violence and lawlessness that ensued. A number of Serbian monks at the time moved from Hilandar to Serbia. To alleviate tensions with his Christian subjects, Murad II had to recognize property rights and privileges of all the monasteries, which in 1457 Sultan Mehmed II additionally confirmed and secured following the 1453 Fall of Constantinople. Thus, the Athonite independence was somewhat guaranteed.

Nobleman from what is today Albania John Castriot donated tax proceeds collected from villages Rostusa and Trebiste in Macedonia to the monastery in 1426. His sons, including The fierce fighter against the Ottoman occupation George Castriot also known as Skanderbeg, were among the remaining local Christian Orthodox aristocrats supporting Hilandar. As John Castriot and his sons purchased adelphates securing their rights to retire and reside in the monastery, the Hilandar Saint George Tower, became known as the "Arbanasi Tower" (Serbian: Арбанашки пирг) in their honor.[16][17] Upon retiring and taking monastic vows, John Castriot's son Reposh joined the Hilandar brotherhood where he died on July 25, 1431. John Castriot followed his son and also joined the monastic community in Hilandar as monk Joachim. He died in the monastery on May 4, 1437.[18]

Following the fall of the Serbian Despotate to the Ottoman Turks in 1459, Hilandar lost major guardians and benefactors as its brotherhood looked for support from other sources. In 1503, the wife of Serbian Despot Stefan Brankovic, Angelina Brankovic asked for the first time Grand Prince of Moscow Vasili III Ivanovich to protect the monastery. Deputy hegumen Paisios with three other monks visited Moscow in 1550 and inquired about help and protection at High Porte in Istanbul from Russian Tsar Ivan IV, also known as Ivan the Terrible. He took monastery Hilandar under his personal protection and built the new monastic cells. In March 1556, Tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich, whose grandmother descended from the noble Serbian family of Yakshich, also granted the Hilandar Monastery a plot of land with all necessary buildings in Moscow within a short walking distance from the Kremlin.[19]

In the 17th century the number of Serbian monks dwindled, and the disastrous fire in 1722 saw a decline: in his account of 1745, Russian pilgrim Vasily Barsky wrote that Hilandar was headed by Bulgarian monks, even though the presence of Serbian monks was also noted.[20] Ilarion Makariopolski, Sophronius of Vratsa and Matey Preobrazhenski had all lived there, and it was in this monastery that Saint Paisius of Hilendar began his revolutionary Slavonic-Bulgarian History. The monastery was dominated by Bulgarians until the late 19th century.[21]

.jpg)

However, in 1913, Serbian presence on Athos was quite big and the Athonite protos was the Serbian representative of Hilandar.[22]

Contemporary

In the 1970s, the Greek government offered power grid installation to all of the monasteries on Mount Athos. The Holy Council of Mount Athos refused, and since then every monastery generates its own power, which is gained mostly from renewable energy sources. During the 1980s, electrification of the monastery of Hilandar took place, generating power mostly for lights and heating.

On March 4, 2004, there was a devastating fire at the Hilandar monastery, with approximately 50% of the walled complex destroyed in the blaze. The blaze damaged the northern half of the walled complex, including the bakery. The library and the monastery's many historic icons were saved or otherwise untouched by the fire. Vast reconstruction efforts are underway, to restore Hilandar.

Sacred objects

Among the numerous relics and other holy objects treasured at the monastery is the Wonderworking Icon of the Theotokos "Of the Akathist", the feast day of which is celebrated on January 12. Since Mount Athos uses the traditional Julian Calendar, the day they name as January 12 currently falls on January 25 of the modern Gregorian Calendar.

The monastery also possesses the Wonderworking Icon of the Theotokos "Of the Three Hands" (Greek: Tricherusa, Serbian: Тројеручицa), traditionally associated with a miraculous healing of St. John Damascene. Around the year 717, St. John became a monk at Mar Sabbas monastery outside of Jerusalem and gave the icon to the monastic community there. Later the icon was offered to St. Sava of Serbia, who gave it to the Hilandar. A copy of the icon was sent to Russia in 1661, from which time it has been highly venerated in the Russian Orthodox Church. This icon has two feast days: June 28 (July 11) and July 12 (July 25). Also Emperor Stefan Dušan's sword is in monastery treasure.

The library holds 181 Greek and 809 Slavic manuscripts, about 20 000 printed books (3 000 in Greek language).

The monastery contains about 45 working monks.

See also

- Hilandar Research Library

- Miroslav Gospels

- Agiou Pavlou monastery

- Dionysiou Monastery

- Docheiariou

- Osiou Gregoriou monastery

References

- Fine 1994, p. 38.

- Ken Parry (10 May 2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 233–. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- Om Datt Upadhya (1 January 1994). The Art of Ajanta and Sopoćani: A Comparative Study : an Enquiry in Prāṇa Aesthetics. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-81-208-0990-1.

- "The administration of Mount Athos". Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- Hilandar – The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity

- Tibor Zivkovic - Charters of the Serbian rulers related to Kosovo and Metochia. p. 15

- "За спас душе своје и прибежиште свом отачеству". Retrieved 2016-04-05.

- John Anthony McGuckin (15 December 2010). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 560–. ISBN 978-1-4443-9254-8.

- "Хиландарски поседи и метоси у југозападној Србији (Кособу и метохији)". hilandar.info. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- Vlasto, The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs, p. 219

- "The Monastery of Hilandar". Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- Bogdanović 1999, Предговор, para. 13, Карејски типик

- Bogdanović 1999, Предговор, para. 14

- "Miraculous Icon - The Virgin with three hands (Bogorodica Trojeručica)". hilandar.info. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- Vásáry, István. Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge University Press=Cambridge, UK. pp. 109–110. ISBN 1139444085.

- Slijepčević, Đoko M. (1983). Srpsko-arbanaški odnosi kroz vekove sa posebnim osvrtom na novije vreme (in Serbian). Himelstir. p. 45. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

Заједно са синовима Константином, Репошем и Ђурђем приложио је Иван Кастриот манастиру Хиландару село Радосуше са црквом св. Богородице и село Требиште....Због тога је и пирг св. Ђорђа прозван »арбанашки пирг». Репош је умро у манастиру Хиландару 25. јула 1431. године и ту је сахрањен. (Together with his sons Konstantin, Repoš and Đurađ, Ivan Kastriot donated village Radosuše with church of saint Mary and village Trebište to the monastery Hilandar... Therefore the tower of Saint George was named "Albanian tower". Repoš died in Hilandar on July 25, 1431 and he was buried there.

- Petković, Sreten (2008) [1989], Hilandar (in Serbian), Belgrade, p. 21, ISBN 978-86-80879-78-9,

... a Ivan Kastriot sa sinovima iz Albanije otkupljuje jedan pirg od Hilandara da bi po potrebi tu mogao naći utočište. (... and Ivan Kastriot with his sons from Albania bought one tower of Hilandar to provide a shelter for them in case of need).

- Mount Athos, Wallachian princes (Voyvodes), John Kastriotis, and the Albanian tower, a dependency of Hilandar Bojović Boško (2006), Balcanica, 2006 Volume, Issue 37, Pages: 81-87. doi:10.2298/BALC0637081B. Full text in French, Abstract in English

- Robert Payne, Nikita Romanoff, "Ivan the Terrible", Rowman & Littlefield, 2002 pp. 436

- "Chilandari". Mount Athos. Archived from the original on 2009-05-02. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

In the 17th century the number of monks coming from Serbia dwindled, and the 18th was a period of decline, following a disastrous fire in 1722. At that time the Monastery was effectively manned by Bulgarian monks who were in dispute with Serbian monks over Hilandar property sale to Bulgarian monks of Zograf monastery.

- "Хилендарски манастир" (in Bulgarian). Православието. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- Panagiotis Christou, "To Agion Oros", Patriarchal Institute of Patristic Studies, Epopteia ed., Athens, 1987 pp. 313-314

Sources

- Dimitrije Bogdanović; Vojislav J. Đurić; Dejan Medaković; Miodrag Đorđević (1997). Chilandar. Monastery of Chilandar.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sreten Petković (1 January 1999). Chilandar. Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Serbia. ISBN 978-86-80879-19-2.

- Branislav Cvetković (2002). Eight centuries of the Monastery of Chilandar at Mount Athos. Zavičajni muzej. ISBN 978-86-902543-2-3.

- Miodrag B. Branković; Marin Brmbolić; Milorad Miljković; Verica Ristić. Chilandar Monastery. Republički zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture. ISBN 978-86-80879-48-2.

- Rajko R. Karišić; Mihajlo Mitrović; Gordana Najčević (2003). Chilandar - unto ages of ages. R. R. Karišić. ISBN 978-86-85345-00-5.

- Панајотис К. Христу (2007). "Манастир Хиландар". Књижевне новине. Belgrade: Projekat Rastko.

- Radić, Radmila. Hilandar u državnoj politici kraljevine Srbije i Jugoslavije 1896-1970. Izdavac Javno Preduzece Sluzbeni List Srj, 1998.

- Živojinović, M. (1998) Vlastelinstvo manastira Hilandara u srednjem veku. u: Subotić G. (ur.) Manastir Hilandar, Beograd: SANU - Galerija

- Đurić, V.J. (1964) Fresques médiévales à Chilandar. in: Actes du XIIe Congrès international d'études Byzantines, Ochride, 1961, Beograd, 68

- Hostetter, W.T. (1998) In the heart of Hilandar: An interactive presentation of the frescoes in the main church of the Hilandar monastery of Mt. Athos. Belgrade, CD-ROM

- Bogdanovich, D., Medakovich, D. Hilandar. Beograd, 1978.

- Todić, Branislav (1999). Serbian Medieval Painting: The Age of King Milutin. Belgrade: Draganić.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hilandar. |

- Official website (in Serbian)

- Hilandar monastery at the Mount Athos website

- Another page dedicated to Hilandar Monastery

- Photos from Hilandar

- Towards Former Beauty Information on the recent fire and reconstruction work (in English)

- Hilandar Research Library Ohio State University Collection—the largest collection of medieval Slavic manuscripts on microform in the world

- Monastery Chilandar, O manastiru Hilandar (in Serbian)