Chester Bennington

Chester Charles Bennington (March 20, 1976 – July 20, 2017) was an American singer, songwriter, musician, and actor. He was best known as the lead vocalist for Linkin Park and was also lead vocalist for the bands Grey Daze, Dead by Sunrise and, between 2013 and 2015, Stone Temple Pilots. Bennington has been credited by several publications as one of the greatest rock vocalists of his generation.[1]

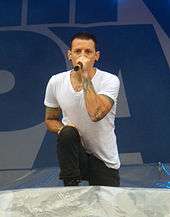

Chester Bennington | |

|---|---|

Bennington performing in June 2014 | |

| Born | March 20, 1976 Phoenix, Arizona, U.S. |

| Died | July 20, 2017 (aged 41) |

| Cause of death | Suicide by hanging |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1992–2017 |

| Spouse(s) | Samantha Olit

( m. 1996; div. 2005)Talinda Bentley

( m. 2006) |

| Children | 6 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Associated acts | |

| Signature | |

| |

Bennington first gained prominence as a vocalist following the release of Linkin Park's debut album Hybrid Theory (2000), which was a worldwide commercial success. The album was certified Diamond by the Recording Industry Association of America in 2005, making it the best-selling debut album of the decade, as well as one of the few albums ever to achieve that many sales.[2] Linkin Park's following studio albums, from Meteora (2003) to One More Light (2017), continued the band's success.

Bennington formed his own band, Dead by Sunrise, as a side project in 2005. The band's debut album, Out of Ashes, was released on October 13, 2009. He became the lead singer of Stone Temple Pilots in 2013 to release the extended play record High Rise on October 8, 2013, via their own record label, Play Pen, but left in 2015 to focus solely on Linkin Park. As an actor, he appeared in films such as Crank (2006), Crank: High Voltage (2009), and Saw 3D (2010).[3]

On July 20, 2017, Bennington was found dead at his home in Palos Verdes Estates, California; his death was ruled a suicide by hanging. Hit Parader magazine placed Bennington number 46 on their list of the "100 Metal Vocalists of All Time".[3] Writing for Billboard, Dan Weiss stated that Bennington "turned nu-metal universal".[4]

Early life

Chester Charles Bennington was born on March 20, 1976, in Phoenix, Arizona.[5] His mother was a nurse, while his father was a police detective who worked on child sexual abuse cases.[6][7] Bennington took an interest in music at a young age, citing the bands Depeche Mode and Stone Temple Pilots as his earliest inspirations,[8] and dreamed of becoming a member of Stone Temple Pilots, which he later achieved when he became their lead singer.[9] Bennington was a victim of sexual abuse from an older male friend when he was seven years old.[10] He was afraid to ask for help because he did not want people to think he was gay or lying, and the abuse continued until he was 13 years old.[11] Years later, he revealed the abuser's identity to his father, but chose not to pursue him after he realized the abuser was a victim himself.[12]

Bennington's parents divorced when he was 11 years old. The abuse and his situation at home affected him so much that he felt the urge to run away and kill people.[11] To comfort himself, he drew pictures and wrote poetry and songs.[11] After the divorce, Bennington's father gained custody of him.[7] Bennington started abusing alcohol, marijuana, opium, cocaine, meth, and LSD.[7][8][12] He was physically bullied in high school. In an interview, he said that he was "knocked around like a rag doll at school, for being skinny and looking different".[13] At the age of 17, Bennington moved in with his mother. He was banned from leaving the house for a time when his mother discovered his drug activity.[7] He worked at a Burger King before starting his career as a professional musician.[8]

Career

Early acts

Bennington first began singing with a band called Sean Dowdell and His Friends? and together they released an eponymous three-track cassette in 1993. Later, Dowdell and Bennington moved on to form a new band, Grey Daze, a post-grunge band from Phoenix, Arizona. The band recorded a Demo in 1993 and two albums: Wake Me in 1994, and ...No Sun Today in 1997. Bennington left Grey Daze in 1998.[14]

Linkin Park

Bennington was frustrated and nearly quit his musical career altogether when Jeff Blue, the vice president of artists and repertoire at Zomba Music in Los Angeles, offered him an audition with the future members of Linkin Park (then 'Xero').[14] Bennington quit his day job at a digital services firm[7] and took his family to California, where he had a successful audition with Linkin Park, who were then called Xero.[14] He managed to record the song for his audition in a day, missing his own birthday celebration in the process. Bennington and Mike Shinoda, the band's other vocalist, made significant progress together, but failed to find a record deal.[14] After facing numerous rejections, Blue, now a vice president of artists and repertoire at Warner Bros., intervened again to help the band sign with Warner Bros. Records.[14]

On October 24, 2000, Linkin Park released their debut album, Hybrid Theory, through Warner Bros. Records. Bennington and Shinoda wrote the lyrics to Hybrid Theory based on some early material.[6] Shinoda characterized the lyrics as interpretations of universal feelings, emotions, and experiences, and as "everyday emotions you talk about and think about."[15][16] Bennington later described the songwriting experience to Rolling Stone magazine in early 2002, "It's easy to fall into that thing – 'poor, poor me', that's where songs like 'Crawling' come from: I can't take myself. But that song is about taking responsibility for your actions. I don't say 'you' at any point. It's about how I'm the reason that I feel this way. There's something inside me that pulls me down."[6] Bennington primarily served as Linkin Park's lead vocalist, but occasionally shared the role with Shinoda. All Music Guide described Bennington's vocals as "higher-pitched" and "emotional", in contrast to Shinoda's hip-hop-style delivery.[8] Both members also worked together to write lyrics for the band's songs.[17]

Hybrid Theory (2000) was certified diamond by the RIAA in 2005.[18] The band's second album, Meteora (2003), reached number one on the Billboard 200 album chart,[19] as did its third album, Minutes to Midnight (2007).[20][21] Linkin Park has sold more than 100 million albums worldwide.[22] The band has won two Grammy Awards, six American Music Awards, four MTV Video Music Awards and three World Music Awards.[23] In 2003, MTV2 named Linkin Park the sixth-greatest band of the music video era and the third-best of the new millennium.[24] Billboard ranked Linkin Park No. 19 on the Best Artists of the Decade chart.[25] In 2012, the band was voted as the greatest artist of the 2000s in a Bracket Madness poll on VH1.[26]

Dead by Sunrise

Bennington co-founded Dead by Sunrise, an electronic rock band from Los Angeles, California, with Orgy and Julien-K members Amir Derakh and Ryan Shuck in 2005.[27][28] Dead by Sunrise made their live debut in May 2008, performing at the 13th anniversary party for Club Tattoo in Tempe, Arizona.[29]

The band released their debut album Out of Ashes on October 13, 2009.[30]

Stone Temple Pilots

In February 2013, Stone Temple Pilots parted ways with long-time lead singer Scott Weiland. The band recruited Bennington to replace Weiland in May 2013. On May 18, 2013, Bennington took the stage at KROQ's Weenie Roast with the band. The setlist included original Stone Temple Pilots songs, as well as their first single with Bennington on vocals called "Out of Time", which debuted on May 19 and was available for free download via their official website. It was later announced by Bennington and the band in an exclusive KROQ interview that he was officially the new frontman of Stone Temple Pilots and discussed the possibility of a new album and tour. The song "Out of Time" is featured on their EP High Rise, which was released on October 8, 2013.[31]

Bennington reflected on joining Stone Temple Pilots, stating, "Every band has its own kind of vibe. Stone Temple Pilots has this sexier, more classic rock feel to it. Linkin Park is a very modern, very tech-heavy type of band. I grew up listening to these guys. When this opportunity came up, it was just like a no-brainer." Bennington stated in interviews that singing lead vocals in Stone Temple Pilots was his lifelong dream. He left the band on good terms due to his commitments with Linkin Park in 2015 and was replaced two years later by X Factor season 3 runner-up Jeff Gutt.[9][32][33]

Other works

In 2005, Bennington appeared on "Walking Dead", the lead single from turntablist Z-Trip's debut album Shifting Gears. Bennington also made a surprise guest appearance during Z-Trip's performance at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in 2005.[34] Bennington re-recorded the Mötley Crüe song "Home Sweet Home" as a duet with the band as a charity single for the victims of Hurricane Katrina in the fall of 2005.[35] He also joined Alice in Chains and performed the song "Man in the Box" at KROQ's Inland Invasion Festival in 2006.[36][37] Bennington performed with Kings of Chaos during their six-show 2016 concert tour.[38]

Personal life

Family and views

Bennington had a son, Jaime (born May 12, 1996), from his relationship with Elka Brand.[39] In 2006, he adopted Brand's other son, Isaiah (born November 8, 1997).[39] He married his first wife, Samantha Marie Olit, on October 31, 1996.[40] They had one child together, Draven Sebastian (born April 19, 2002).[39] Bennington's relationship with his first wife declined during his early years with Linkin Park, and they divorced in 2005.[41] In 2006, he married Talinda Ann Bentley, a former Playboy model with whom he had three children: Tyler Lee Bennington (born March 16, 2006) and twins Lily and Lila (born November 9, 2011).[42]

Chester and Talinda Bennington were harassed by a cyberstalker named Devon Townsend (not to be confused with Canadian musician Devin Townsend) for almost a year. Townsend was found guilty of tampering with the couple's email, as well as sending threatening messages, and was later sentenced to two years in prison.[43]

Bennington struggled with drug and alcohol abuse. Bennington overcame his drug addiction and would go on to denounce drug use in future interviews.[44] In 2011, he said he had quit drinking, noting, "I just don't want to be that person anymore."[45] Bennington later battled an alcohol addiction during his tenure with Linkin Park, which he overcame following an intervention from his bandmates.[46]

Bennington was a tattoo enthusiast.[47] He had done work and promotions with Club Tattoo, a tattoo parlor in Tempe, Arizona. Club Tattoo is owned by Sean Dowdell, Bennington's friend since high school with whom he played in two bands.[48][49] Bennington was a fan of the Phoenix Suns,[50][51] Arizona Cardinals, Arizona Diamondbacks, and Arizona Coyotes.[52]

In a January 2011 interview, in response to the 2011 Tucson shooting, Bennington said, "There's a non-violent way to express yourself and get your point across – regardless of what you're saying or what your point is. In a free society, people have a right to believe whatever they want to believe. That's their business and they can speak their mind. But nobody, even in a free society, has the right to take another person's life. Ever. That's something that we really need to move beyond."[53]

Bennington was a critic of U.S. president Donald Trump. On January 29, 2017, he tweeted that Trump was "worse than terrorism". This tweet resurfaced in July 2020 after Linkin Park sent Trump a cease and desist order for using "In the End" in an ad for his re-election campaign that year.[54]

Health and injuries

Bennington was plagued with poor health during the making of Meteora, and struggled to attend some of the album's recording sessions.[55] In the summer of 2003, he began to suffer from extreme abdominal pain and gastrointestinal issues while filming the music video for "Numb" in Prague. He was forced to return to the United States for surgery, and filmed the remainder of the music video in Los Angeles.[56][57]

Bennington sustained a wrist injury in October 2007 while attempting to jump off a platform during a show in Melbourne at the Rod Laver Arena. Despite the injury, he continued to perform the entire show with a broken wrist, before heading to the emergency room where he received five stitches.[58][59]

In 2011, Bennington fell ill again, and Linkin Park was forced to cancel three shows and reschedule two from the A Thousand Suns World Tour.[60] Bennington injured his shoulder during the band's tour in Asia and was advised by doctors to have immediate surgery, cancelling their final show at Pensacola Beach, Florida, and ending their tour.[61]

Bennington injured his ankle in January 2015 during a basketball game.[62] He attempted to cope with the injury and perform with the aid of crutches and a knee scooter. Linkin Park later canceled the remainder of their tour to allow Bennington to undergo surgery and recover.[63][64][65]

Death

.jpg)

At around 9:00 a.m. PDT on July 20, 2017, Bennington was found dead by his housekeeper at his home in Palos Verdes Estates, California.[66][67] His death was ruled a suicide by hanging. Bandmate Mike Shinoda confirmed his death on Twitter, writing, "Shocked and heartbroken, but it's true. An official statement will come out as soon as we have one."[68] On July 21, Brian Elias, the chief of operations for the office of the medical examiner-coroner, confirmed that a half-empty bottle of alcohol was found at the scene, but no other drugs were present.[69] A toxicology report released in December reported "a trace amount" of alcohol in Bennington's system at the time of death.[70] The band canceled the rest of their One More Light Tour and refunded tickets.[71] Following his death, Linkin Park took to a hiatus period until April 2020, when Dave Farrell revealed the band was working on new music.[72][73]

Bennington's funeral was held on July 29 at South Coast Botanic Garden in Palos Verdes, California. In addition to his family members and close friends, many musicians who toured or played with Linkin Park were also in attendance. The service also included a full stage for musical tributes.[74]

Bennington's death occurred on what would have been Chris Cornell's 53rd birthday.[75] Cornell's death was also ruled as suicide by hanging two months earlier.[75] Bennington was a close friend of Cornell's.[76] Bennington had commented on Cornell's death on Instagram, "I can't imagine a world without you in it."[75] Shinoda noted that Bennington was very emotional when the band performed "One More Light" in his honor on Jimmy Kimmel Live!,[77] and could not finish singing the song because he started getting choked up during both the rehearsal and the live performance.[78] The band was due to record a live performance of their single "Heavy" on the show, but decided instead to play "One More Light" after hearing the news about Cornell's death because the song is about the loss of a friend.[78] Bennington sang Leonard Cohen's song "Hallelujah" at Cornell's funeral.[75] He was also the godfather of Cornell's son Christopher.[75]

Memorial and tributes

Bennington filmed an episode of Carpool Karaoke six days before his death. Bennington's family allowed the episode to be aired on October 12, 2017.[79] On August 27, during the 2017 MTV Video Music Awards ceremony, Jared Leto received media attention for his tribute to Bennington and Chris Cornell.[80] Some of his former bandmates from Dead by Sunrise and Grey Daze united to perform a tribute for Bennington during a concert on September 2 in Las Vegas.[81] Linkin Park also hosted a public tribute for Bennington in Los Angeles on October 27, titled Linkin Park and Friends: Celebrate Life in Honor of Chester Bennington. The event featured the band's first performance following his death, along with performances from Blink-182, members of System of a Down, Korn, Avenged Sevenfold, Bring Me the Horizon and Yellowcard, and the singer Kiiara, among others.[82][83][84]

Rapper Jay-Z paid tribute to Bennington on several occasions by performing "Numb/Encore" live. Jay-Z and Bennington (with Linkin Park) collaborated on the song. Coldplay's Chris Martin paid tribute to Bennington during the band's North American tour concert at MetLife Stadium, playing an acoustic version of "Crawling" on piano.[85] Several other artists, including Ryan Key (formerly of Yellowcard), rapper Machine Gun Kelly, Imagine Dragons and Godsmack, also either covered Linkin Park songs (usually "Crawling") or played their own songs during concerts as tribute to Bennington in the days and months following his death. During the 60th Annual Grammy Awards's annual in memoriam tribute, rapper Logic performed the song "1-800-273-8255" live alongside Alessia Cara and Khalid as a tribute to both Cornell and Bennington. The song's title is the phone number of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.[86]

Producer Markus Schulz made a trance remix of the Linkin Park song "In the End" as tribute to Bennington after his death which he debuted at Tomorrowland.[87]

Musical style and influences

Bennington possessed a three octave tenor vocal range, beginning at the low bass G (G2), and reaching its peak at the tenor G (G5). His vocals showed tremendous durability for the entirety of his career.[88] Altheapi of Rolling Stone wrote: "Bennington's voice embodied the anguish and wide-ranging emotions of the lyrics, from capturing life's vulnerable moments to the fury and catharsis found in his belted screams, which he would often move between at the turn of a dime."[89]

Talking about his favorite bands and influences, Bennington mentioned Stone Temple Pilots, Alice in Chains, Arcade Fire, Circle Jerks, Descendents, Deftones, Jane's Addiction, Metallica, Ministry, Minor Threat, Misfits, The Naked and Famous, Nine Inch Nails, Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Refused, Skinny Puppy, Soundgarden, and A Tribe Called Quest.[90][91] Bennington also considered himself as "a huge Madonna fan", crediting her for making him grow up wanting to be a musician.[92]

Legacy

Several publications have commented on the music legacy Bennington left with the bands and projects he worked in.[93][94] While describing the success of Bennington and Linkin Park, Allmusic's Andrew Leahey said, "Although rooted in alternative metal, Linkin Park became one of the most successful acts of the 2000s by welcoming elements of hip-hop, modern rock, and atmospheric electronica into their music ... focusing as much on the vocal interplay between singer Chester Bennington and rapper Mike Shinoda".[95] Writing for Billboard, Dan Weiss stated that Bennington "turned nu-metal universal," as he was "clearly an important conduit for his far-ranging audience".[4]

The New York Times' Jon Caramanica commented that Bennington's ability to "pair serrated rawness with sleek melody" separated him from other contemporary singers, and also from the artists he was influenced by. Caramanica noted, "He was an emo sympathizer in a time when heavy metal was still setting the agenda for mainstream hard rock, and a hip-hop enthusiast who found ways to make hip-hop-informed music that benefited from his very un-hip-hop skill set". As Bennington acquired influences from industrial and hardcore punk acts, the journalist believed this was the factor that made Linkin Park survive the "rise and precipitous fall of the rap-rock era", calling the musician "a rock music polymath".[96] Mikael Wood of the Los Angeles Times argued, "Perhaps more than Linkin Park's influential sound, Bennington's real artistic legacy will be the message he put across – the reassurance he offered from the dark".[97]

BBC's Steve Holden called Bennington the "voice of a generation", saying his voice was arguably Linkin Park's greatest asset.[98] Jonathan McAloon of The Daily Telegraph commented, "Bennington’s death will have an impact on many millennials because his voice was the sound of their millennium".[99] While talking about Linkin Park's popularity, Corey Apar, of AllMusic, commented, "Bennington's oft-tortured vocals became one of the most distinctive in the alternative rock scene".[100] Writing for The Guardian, Ben Beaumont-Thomas noted "Bennington’s decision to sing clearly and openly was, therefore, more radical than he is given credit for, and indeed more socially valuable". The journalist continued to discuss Bennington's impact, commenting,

His cleanly articulated tales of emotional struggle gave millions the sense that someone understood them, and the huge sound of his band around him magnified that sense, moving listeners from the psychic space of their bedrooms into an arena of thousands of people who shared their pain.[101]

James Hingle echoed this sentiment, writing for Kerrang! he said that Bennington "was one of the most honest vocalists out there when it came to his mental health".[102] In the same topic, William Goodman from Billboard said Bennington and fellow musicians Chris Cornell and Scott Weiland "helped define a generation of the hard rock sound, who were tied together artistically and personally".[1]

The Straits Times' music correspondent Eddino Abdul Hadi stated Bennington was an inspiration to many artists in the Singapore music scene.[103] Calum Slingerland, editor of the Canadian periodical Exclaim!, expressed, "[H]is influence has been felt in the worlds of rock, metal, rap, and beyond".[104]

After Bennington's death, his widow Talinda Bennington launched a campaign called 320 Changes Direction in honor of her husband to help break the stigma surrounding mental illness.

During a Twitch live-stream, Mike Shinoda confirmed the existence of an unreleased Linkin Park song, titled "Friendly Fire", which features vocal tracks Bennington recorded during the One More Light sessions.[105]

Discography

With Grey Daze

| Year | Album details | Peak chart positions | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUS | AUT | GER | SWI | UK | UK Rock |

US | |||||||

| Wake Me |

|

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||||

| ...No Sun Today |

|

— | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||||

| Amends |

|

30 | 29 | 9 | 17 | 62 | 1 | 75 | |||||

| "—" denotes a recording that did not chart or was not released in that territory. | |||||||||||||

Singles

| Title | Year | Peak chart positions | Album | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Main. [106] |

US Rock [107] |

US Rock Air. [108] | |||

| "What's In the Eye?" | 2020 | — | — | — | Amends |

| "Sickness" | 2 | 35 | 11 | ||

| "Sometimes" | — | — | — | ||

| "Soul Song" | — | 40 | — | ||

| "B12" | 34 | — | — | ||

Music videos

- "What's In the Eye" (2020)

- "Sickness" (2020)

- "Soul Song" (2020)

- "B12" (2020)

With Linkin Park

- Hybrid Theory (2000)

- Meteora (2003)

- Minutes to Midnight (2007)

- A Thousand Suns (2010)

- Living Things (2012)

- The Hunting Party (2014)

- One More Light (2017)

With Dead by Sunrise

- Out of Ashes (2009)

Album contributions and singles

| Year | Artist | Song | Release |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Stone Temple Pilots | "Wonderful (Live)" | The Family Values 2001 Tour |

| 2002 | Chester Bennington | "System" | Queen of the Damned soundtrack |

| Cyclefly | "Karma Killer" | Crave | |

| DJ Lethal | "Cry To Yourself" | N/A | |

| 2004 | Handsome Boy Modeling School featuring DJ Q-bert, Grand Wizard Theodore, Jazzy Jay, Lord Finesse, Mike Shinoda, Rahzel & Chester Bennington / Tim Meadows | "Rock N' Roll (Could Never Hip Hop Like This) (Part 2) / Knockers" | White People |

| 2005 | Z-Trip | "Walking Dead" | Shifting Gears |

| Mötley Crüe | "Home Sweet Home" (remake) | Non-album charity single | |

| 2006 | Chester Bennington | "Morning After (Julien-K Remix)" | Underworld: Evolution (soundtrack) |

| Mindless Self Indulgence | "What Do They Know? (Mindless Self Indulgence Vs. Julien-K & Chester Bennington Remix)" | Another Mindless Rip Off | |

| 2007 | Young Buck | "Slow Ya Roll" | Buck the World |

| 2008/2010 | Chris Cornell | "Hunger Strike (Live at Projekt Revolution 2008)" | Songs from the Underground |

| 2010 | Santana featuring Chester Bennington & Ray Manzarek | "Riders on the Storm" (The Doors cover) | Guitar Heaven: The Greatest Guitar Classics of All Time |

| 2019 | Mark Morton featuring Chester Bennington | "Cross Off" | Anesthetic[109][110] |

Filmography

Bennington made a cameo appearance in the 2006 film Crank as a customer in a pharmacy.[112] He later appeared as a horse-track spectator in the film's 2009 sequel, Crank: High Voltage.[113] Bennington also played the role of the ill-fated racist Evan in the 2010 film Saw 3D.[114] He was one of several rock musicians who spoke about the industry on Jared Leto's 2012 documentary, Artifact.[115]

Bennington was working with Church on developing an upcoming television show, Mayor of the World, with executive producer Trip Taylor.[116]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Crank | Pharmacy Stoner | [112] |

| 2009 | Crank: High Voltage | Hollywood Park Guy | [113] |

| 2010 | Saw 3D | Evan | [117] |

| 2012 | Artifact | Himself | [115] |

References

- Goodman, William (July 21, 2017). "Chester Bennington, Chris Cornell & Scott Weiland: A Legacy of Pained Rock Powerhouses". Billboard. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- "Linkin Park – Hybrid Theory Review". sputnikmusic. September 2, 2006. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- Bucher, Chris (July 20, 2017). "Chester Bennington Dead: Top Linkin Park Songs & Albums". Heavy.com. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- Weiss, Dan (July 20, 2017). "Chester Bennington Turned Nu-Metal Universal". Billboard. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Shaw, Phil (July 25, 2017). "Chester Bennington: Lead singer of Linkin Park remembered". The Independent. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- Fricke, David. “Rap Metal Rulers” Archived December 24, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone No. 891, March 14, 2002

- Bryant, Tom (January 23, 2008). "Linkin Park, Kerrang!". Kerrang!. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- Apar, Corey, Chester Bennington Biography, mtv.com, Retrieved on June 27, 2007.

- "Celebrará Chester Bennington cumpleaños 35 con nuevo sencillo". El Porvenir (in Spanish). March 19, 2011. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington: 'I was a raging alcoholic'". nme.com. July 14, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- Bryant, Tom (January 23, 2008). "Linkin Park, Kerrang!". Kerrang!. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- Simpson, Dave (July 7, 2011). "Linkin Park: 'We're famous, but we're not celebrities'". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- Beaumont, Mark (July 21, 2017). "Chester Bennington Obituary: 1976–2017". NME. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Rolling Stone Magazine, Linkin Park – Biography Archived December 24, 2005, at the Wayback Machine (March 14, 2002), The Linkin Park Times; retrieved on June 24, 2007.

- BBC Radio 1, Evening Session Interview with Steve Lamacq, June 13, 2001

- "BBC Session Interview". LP Times. Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- Soghomonian, Talia (May 2003). "interview with Mike Shinoda of Linkin Park". NY Rock. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- Recording Industry Association of America, RIAA Record Sales Archived July 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 13, 2007

- Zahlaway, Jon (April 2, 2003). "Linkin Park's 'Meteora' shoots to the top". Soundspike: Album Chart. Archived from the original on May 4, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- Billboard.com, M2M holds the top slot for the current week. Retrieved May 28, 2007

- Billboard.com, Linkin Park Scores Year's Best Debut With 'Midnight'. Retrieved May 28, 2007

- Shaw, Phil (July 25, 2017). "Chester Bennington: Lead singer of Linkin Park remembered". The Independent. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "List of awards and nominations received by Linkin Park", Wikipedia, April 23, 2019, retrieved June 16, 2019

- Negri, Andrea (October 10, 2003). "22 greatest bands? Something 2 argue about". Houston Chronicle.

- Billboard Artists Of The Decade, . Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- "BRACKET MADNESS: Linkin Park Is The Greatest Artist Of The 00s". September 6, 2012. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- "Dead By Sunrise Release New Video". SoundSphere Mag. September 8, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Heaney, Gregory. "Dead By Sunrise Bio". AllMusic. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Fuoco, Christina (May 12, 2008). "Chester Bennington Talks New Band Dead by Sunrise, Next Linkin Park Album". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Graff, Gary. "Linkin Park's Bennington Talks New Band, Debut". Billboard. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Hartmann, Graham (October 2, 2013). "Linkin Park DJ Joe Hahn Cool With Chester Bennington's Stone Temple Pilots Gig". Loudwire. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Stanisci, Grace (May 23, 2014). "Stone Temple Pilots fans bash new lead singer, Linkin Park's Chester Bennington". Sound Check. Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on June 9, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- Young, Alex (November 15, 2017). "Stone Temple Pilots debut new singer Jeff Gutt with new single "Meadow": Stream". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- Lewis, Don (May 2, 2005). "Live at Coachella '05". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- "Motley Crue to Donate All Proceeds From 'Home Sweet Home' Remake to Charity". Blabbermouth. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- "Guns N' Roses Take On Aguilera, Chester Bennington Joins Alice In Chains At Inland Invasion". MTV. September 25, 2006. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- "Chester rockin with Alice in Chains". October 11, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- "LINKIN PARK's CHESTER BENNINGTON: Don't Call KINGS OF CHAOS A 'Supergroup'". Blabbermouth.net. December 1, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- Orfanides, Effie (July 20, 2017). "Chester Bennington's Kids: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy.com. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Chester Bennington Profile Archived December 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, celebritywonder.com; retrieved on June 27, 2007.

- Montgomery, James, Linkin Park's Minutes to Midnight Preview: Nu-Metallers Grow Up (May 7, 2007), MTV News; retrieved on June 24, 2007.

- Runtagh, Jordan; Nelson, Jeff (July 20, 2017). "Linkin Park Frontman Chester Bennington, 41, Found Dead of Apparent Suicide". People. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- "Linkin Park singer's stalker sentenced - USATODAY.com". Associated Press. ALBUQUERQUE, NM.: usatoday30.usatoday.com. February 20, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- Bradenton Herald, Bradenton: Mo' Money Mo' Problems Archived May 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (August 13, 2004), Linkin Park Association; retrieved on June 27, 2007.

- "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington: 'I was a raging alcoholic'". nme.com. July 14, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- Gaita, Paul (July 14, 2011). "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington: Band's Intervention Saved my Life". The Fix. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- "Chester Bennington – Biography". metal.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- Brink, etnies and Chester Bennington Launch Club Tattoo Collaboration with Exclusive Art Show in NYC! Archived March 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (March 21, 2007); retrieved on June 24, 2007.

- ClubTattoo.com, Press Room Archived June 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine; retrieved on June 24, 2007.

- Twitter / ChesterBe: The Suns are the best. Twitter.com. Retrieved on August 25, 2013.

- Twitter / ChesterBe: I LOVE the Suns!!!. Twitter.com. Retrieved on August 25, 2013.

- "STONE TEMPLE PILOTS' CHESTER BENNINGTON Guests On 'Ferrall on the Bench' (Audio)". BlabberMouth.

- Fischer, Reed (January 11, 2011). "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington Responds to Arizona Shooting". New Times Broward-Palm Beach. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- "Chester Bennington's anti-Trump posts resurface after Linkin Park stop him using their songs". Indy100.

- Warner Bros. Records, "The Making of Meteora" (2003) [DVD]; released on March 25, 2003.

- Wiederhorn, Jon (July 24, 2003). "Surgery May Stop Linkin Park Singer From Vomiting While Singing". MTV. mtv.com. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington Doing Fine". Linkin Park News. Yahoo! Music. July 11, 2003. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- Chester Bennington (October 17, 2007). Chester's Broken Wrist (The Official Linkin Park YouTube Channel) (Adobe Flash) (YouTube video). Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington is Accident Prone". UpVenue. February 25, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- Diaz, Julio (October 4, 2011). "DeLuna Fest loses Linkin Park". Pensacola News Journal. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- Linkin Park (October 5, 2011). "LINKIN PARK WITHDRAW FROM DELUNA FEST". linkinpark.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011.

- Oswald, Derek (March 12, 2015). "[AltWire Interview] Chester Bennington – "We'll Be Playing Some Songs That We Haven't Played Before…"". AltWire. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- Childers, Chad (January 20, 2015). "Linkin Park Call Off Remaining Tour Dates After Chester Bennington Leg Injury". Loudwire. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- "THE HUNTING PARTY TOUR – CANCELLED". linkinpark.com. January 20, 2015. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- Zadrozny, Anya (January 26, 2015). "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington Shares Gnarly Post-Surgery Photo". Loudwire. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Grow, Cory. "Chester Bennington, Linkin Park Singer, Dead at 41". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington dies". BBC News. July 20, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- "Mike Shinoda on Twitter". twitter.com. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- "Coroner confirms Chester Bennington died by hanging; Linkin Park cancels tour". USA Today. July 21, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- Payne, Chris (December 5, 2017). "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington: Toxicology Report Released". Billboard. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- "Linkin Park cancels North American tour after Chester Bennington death". BBC. July 21, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- Mike Shinoda as told to Ilana Kaplan (March 29, 2018). "Linkin Park's Mike Shinoda on Life After Chester Bennington". Vulture.com. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- "LINKIN PARK HAVE BEEN WORKING ON NEW MUSIC". Kerrang!. April 28, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Bitette, Nicole (July 30, 2017). "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington laid to rest in private funeral ceremony near his home". New York Daily News. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- "Linkin Park singer dies on his good friend Chris Cornell's birthday". CNN. July 20, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Almasy, Steve (July 20, 2017). "Linkin Park singer dies on his good friend Chris Cornell's birthday". CNN. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- "Linkin Park Performs "One More Light"", YouTube, May 19, 2017, archived from the original on October 29, 2017, retrieved November 9, 2017

- Radio.com (July 20, 2017), Chester Bennington’s Bandmate: Linkin Park Singer Was Hit Hard by Chris Cornell’s Suicide, retrieved July 21, 2017

- Reed, Ryan (August 9, 2017). "James Corden: Chester Bennington's 'Carpool Karaoke' Is Family's Decision". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- Stedman, Alex (August 27, 2017). "Jared Leto Delivers Heartfelt Tribute to Chester Bennington, Chris Cornell at MTV Video Music Awards". Variety. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- Mack, Emmy (September 4, 2017). "Watch Chester Bennington's Former Bandmates Perform An Emotional Acoustic Tribute". Music Feed. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- Eisinger, Dale (September 19, 2017). "Linkin Park's Chester Bennington Tribute to Include Blink-182, Members of Korn, System of a Down". Variety. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- Blistein, Jon (August 23, 2017). "Linkin Park Plan Public Event to Honor Chester Bennington". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- Eisinger, Dale (September 19, 2017). "Linkin Park's Mike Shinoda Says Rick Rubin Convinced the Band to Perform Again". Spin. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- "Watch Coldplay pay touching tribute to Linkin Park's Chester Bennington". Metro. August 2, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- "Watch Logic, Khalid, & Alessia Cara Perform '1-800-273-8255' at Grammys". Rap-Up. January 28, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- "Markus Schulz honors Chester Bennington with 'In The End' bootleg". Dancing Astronaut. July 29, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- "Chester Bennington | The Range Place". therangeplace.boards.net. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- Legaspi, Althea (July 21, 2017). "Flashback: Chester Bennington Sings Adele's 'Rolling in the Deep'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Farrier, David (April 28, 2014). "Chester Bennington talks Linkin Park's The Hunting Party". 3 News. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Oswald, Derek (March 12, 2015). "Chester Bennington – 'We'll Be Playing Some Songs That We Haven't Played Before...'". AltWire. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- "Remembering Our Time with Chester Bennington". Elvis Duran and the Morning Show. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Turman, Katherine (July 20, 2017). "Chester Bennington and Linkin Park: A Musical Legacy of Darkness and Hope". Variety. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Connick, Tom (July 21, 2017). "How Chester Bennington articulated my generation's angst". Dazed. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- "Linkin Park - Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Caramanica, Jon (July 20, 2017). "Chester Bennington Brought Rock Ferocity to Linkin Park's Innovations". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Wood, Mikael (July 21, 2017). "Appreciation Linkin Park's Chester Bennington was a voice of reassurance from the dark". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- "Chester Bennington: Linkin Park vocalist 'took his own life'". BBC News. July 20, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- McAloon, Jonathan (July 21, 2017). "Why the passing of Linkin Park's Chester Bennington will break millions of millennial hearts". The Telegraph. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- Apar, Corey. "Chester Bennington Bio". AllMusic. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (July 21, 2017). "Linkin Park singer Chester Bennington soothed the angst of millions". The Guardian. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Hingle, James (July 21, 2017). "A Tribute To Chester Bennington". Kerrang!. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Hadi, Eddino Abdul (July 21, 2017). "Recommended by Linkin Park singer Chester Bennington influenced many in the Singapore music scene". The Straits Times. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- Slingerland, Calum (July 20, 2017). "The World Reacts to Chester Bennington's Death". Exclaim!. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- "Mike Shinoda on Unreleased Linkin Park Song Featuring Chester Bennington Vocals: 'You're Gonna Have to Wait Literally Years to Hear It'". Ultimate-guitar.com. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- "Mainstream Rock Charts: Week of May 23, 2020". Billboard. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Hot Rock Songs Chart: Week of May 23, 2020". Billboard. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Rock Airplay: Week of May 30, 2020". Billboard. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Kaufman, Spencer. "Lamb of God's Mark Morton to release album featuring Chester Bennington, Randy Blythe, Myles Kennedy, and more". Consequence of Sound. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- brownypaul (December 18, 2018). "Lamb of God's Mark Morton announces solo collaborative album 'Anesthetic' featuring a STACK OF GUESTS!!!". Wall Of Sound. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- "Hellflower". American Voodoo Records. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- Cohen, Johnathon (August 29, 2006). "Linkin Park Hits iTunes, New Album Not Quite Ready". Billboard. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- Greenberg, Alexandra (April 3, 2009). "MAYNARD JAMES KEENAN & CHESTER BENNINGTON MAKE CAMEO IN 'CRANK: HIGH VOLTAGE'". Mitch Schneider Organization. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- Barton, Steve (August 31, 2010). "New Saw 3D Image Tortures Linkin Park's Chester Bennington". DreadCentral. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- Mobarak, Jared. "Artifact". Film Stage. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- "Reaper's Forge". Reapersforge.com. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- JEN (July 22, 2010). "Saw 3D". cbennington Blog. Archived from the original on August 5, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2010.