Chelyabinsk

Chelyabinsk (Russian: Челя́бинск, IPA: [tɕɪˈlʲæbʲɪnsk] (![]()

Chelyabinsk Челябинск | |

|---|---|

City[1] | |

| |

Flag .svg.png) Coat of arms | |

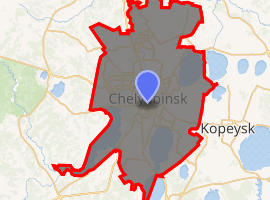

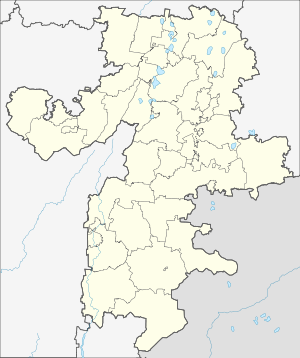

Location of Chelyabinsk

| |

Chelyabinsk Location of Chelyabinsk  Chelyabinsk Chelyabinsk (Chelyabinsk Oblast) | |

| Coordinates: 55°09′17″N 61°22′33″E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Chelyabinsk Oblast |

| Founded | 1736[2] |

| City status since | 1787[2] |

| Government | |

| • Body | Council |

| • Head | Natalya Kotova (acting) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 530 km2 (200 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 220 m (720 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,130,132 |

| • Estimate (2018)[5] | 1,202,371 (+6.4%) |

| • Rank | 9th in 2010 |

| • Density | 2,100/km2 (5,500/sq mi) |

| • Subordinated to | City of Chelyabinsk[1] |

| • Capital of | Chelyabinsk Oblast[1], City of Chelyabinsk[1] |

| • Urban okrug | Chelyabinsky Urban Okrug[1] |

| • Capital of | Chelyabinsky Urban Okrug[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (MSK+2 |

| Postal code(s)[7] | 454xxx |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 351[8] |

| OKTMO ID | 75701000001 |

| City Day | September 13 |

| Website | www |

The area of Chelyabinsk contained the ancient settlement of Arkaim, which belonged to the Sintashta culture. In 1736, a fortress by the name of Chelyaba was founded on the site of a Bashkir village. Chelyabinsk was granted town status by 1787. Chelyabinsk began to grow rapidly by the late 20th century as a result of the construction of railway links to European Russia and Siberia, including the Trans-Siberian Railway. Its population reached 70,000 by 1917. Under the Soviet Union, Chelyabinsk became a major industrial centre during the 1930s. The Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant was built in 1933. During World War II, the city was a major contributor to the manufacture of tanks and ammunition.

Chelyabinsk remains an important industrial centre, especially heavy industries such as metallurgy and military production. It is home several educational institutions, mainly South Ural State University and Chelyabinsk State University. In 2013, the Chelyabinsk meteor exploded over the Ural Mountains, with fragments falling into and near the city. The blast of the explosion caused many hundreds of injuries, some of them serious, mostly caused by glass fragments from shattered windows. The Chelyabinsk Regional Museum contains fragments of the meteorite.

History

Ancient Vedic civilization

Archaeologists have discovered ruins of the ancient town of Arkaim in the vicinity of the city of Chelyabinsk. Ruins and artifacts in Arkaim and other sites in the region indicate a relatively advanced civilization existing in the area since the 2nd millennium BCE, which was of proto-Indo-Iranian or Proto-Vedic origin. [12]

The Arkaim site, located in the Sintashta-Petrovka cultural area, was known by Russian archaeologists for at least 70 years, however it was mostly ignored by non-Russian anthropological circles. The borders of the Sintashta-Petrovka cultural area run along the eastern Urals of the Eurasian steppe to about 400 km south of Chelyabinsk and to the east for about 200 km. 23 archaeological sites are recognized as being part of this area.

The sites resemble towns, laid out in round, square, or oval shapes. Although most of the sites have been discovered by aerial photography, only two, Arkaim and Sintashta, have been thoroughly excavated. These sites are characterized by their fortification, connected houses, and extensive evidence of metallurgy.[13][14]

The people of the Sintashta culture are thought to have spoken Proto-Indo-Iranian, the ancestor of the Indo-Iranian language family. This identification is based primarily on similarities between sections of the Rigveda, an Indian religious text which includes ancient Indo-Iranian hymns recorded in Vedic Sanskrit, with the funerary rituals of the Sintashta culture, as revealed by archaeological studies in the area.[15] [16]

Modern Russian history

The fortress of Chelyaba, from which the city takes its name, was founded at the location of the Bashkir village of Chelyaby (Bashkir: Силәбе, Siläbe) by colonel Alexey (Kutlu-Muhammed) Tevkelev in 1736[2] to protect the surrounding trade routes from possible attacks by Bashkir outlaws. During Pugachev's Rebellion, the fortress withstood a siege by the rebel forces in 1774, but was eventually captured for several months in 1775. In 1782, Chelyabinsk became a seat of the uyezd of Ufa Viceroyalty, which was later reformed into Orenburg Governorate. In 1787, Chelyabinsk was granted town status by the government.

Until the late 19th century, Chelyabinsk was a small provincial town. In 1892, the Samara-Zlatoust Railway was completed, which connected it with Moscow and the rest of European Russia. Also in 1892, construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway started from Chelyabinsk, and in 1896, the city was linked to Ekaterinburg. Chelyabinsk then became the main hub for travel to Siberia. For fifteen years, more than fifteen million people - a tenth of Russia's population at the time - passed through Chelyabinsk. Some of them remained in Chelyabinsk, which contributed to its rapid growth. In addition a so-called “customs fracture” was created in Chelyabinsk, which imposed duties on the shipment of goods between the European and Asian parts of Russia, which led to the emergence of mills and notably, a tea-packing factory. As a result, Chelyabinsk became a major trade center. Its population reached 20,000 inhabitants by 1897, 45,000 by 1913, and 70,000 by 1917. Because of its rapid growth at the turn of the 20th century, similar to that of midwestern American cities, Chelyabinsk was sometimes called "the Chicago of the Urals".[17]

During the first Five-Year Plans of the 1930s, Chelyabinsk experienced rapid industrial growth. Several important factories, including the Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant and the Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Plant, were built at this time. During World War II, Joseph Stalin decided to move a large part of Soviet manufacturing to areas removed from the reach of the advancing German military as part of a general exodus from western occupied areas. This brought new industries and thousands of workers to Chelyabinsk, including facilities for the production of T-34 tanks and Katyusha rocket launchers. During World War II, the city's industries produced 18,000 tanks and 48,500 tank diesel engines as well as over 17 million units of ammunition. During that time Chelyabinsk was informally called “Tankograd” (English: “Tank City”). During World War II, the S.M. Kirov Factory no. 185 or “OKMO” was moved to Chelyabinsk from Leningrad to produce heavy tanks, although it was transferred to Omsk after 1962.

2013 meteor

Shortly after dawn on February 15, 2013, a superbolide meteor descended at over 55,000 kilometers per hour (34,000 mph) over the Ural Mountains, exploding at an altitude of 25–30 kilometers (16–19 mi).[18]

The meteor created a momentary flash as bright as the sun and generated a shock wave that injured over a thousand people. Fragments fell in and around Chelyabinsk. Interior Ministry spokesman Vadim Kolesnikov said 1,100 people had called for medical assistance following the incident, mostly for treatment of injuries from broken glass by the explosions. One woman suffered a broken spine.[19] Kolesnikov also said about 600 square meters (6,000 sq ft) of a roof at a zinc factory had collapsed. A spokeswoman for the Emergency Ministry told the Associated Press that there was a meteor shower; however, another ministry spokeswoman was quoted by the Interfax news agency as saying it was a single meteor.[20][21][22] The size has been estimated at 17 meters (56 ft) diameter with a mass of 10,000[23][24] or 11,000[25] metric tons. The power of the explosion was about 500 kilotons of TNT (about 1.8 PJ), which is 20–30 times more energy than was released from the atomic bomb detonated in Hiroshima. The city managed to avoid large casualties and destruction due to the high altitude of the explosion.

Administrative and municipal status

Chelyabinsk is the administrative center of the oblast.[1] Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is incorporated as the City of Chelyabinsk, an administrative unit with a status equal to that of the oblast's districts.[1] As a municipal division, the City of Chelyabinsk is incorporated as Chelyabinsky Urban Okrug.[1] In June 2014, Chelyabinsk's seven city districts were granted civil status.[26]

Geography

Chelyabinsk is located east of the Ural Mountains, 200 km south of Yekaterinburg. It is elevated 200-250 meters above sea level.

The city is bisected by the Miass River, which is regarded as the border between the Urals and Siberia. This is reflected in the geology of the area, with the granite foothills of the Ural Mountains to the west and the lower sedimentary rock of the West Siberian Plain to the east.

The Leningrad bridge crosses the river, due to this it is known as “the bridge between the Urals and Siberia". Chelyabinsk itself is also known as "the gateway to Siberia".[27]

Like Rome, Constantinople, San Francisco and Moscow, Chelyabinsk is said to be located on seven hills.[28]

Climate

The city has a Humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb) similar to that of the Canadian prairies, despite the city being located further north. The average temperature in January is well below the freezing point at -14°C/6.6 °F. July has a relatively cool average of 19°C/66.7 °F, and the annual average is a few degrees above the freezing point at 3°C/37.8 °F, indicating some moderation. The range of extremes allegedly reaches 70°C/158 °F, claimed to be typical of a mid-latitude climate on a large continent such as Eurasia.[29]

The majority of precipitation occurs in the summer, with less in the winter. The month of July experiences the most, with an average 87mm/3.44'' of precipitation, while January, the driest month, experiences 15mm/0.6''. Total precipitation reaches an average of 429mm/16.9'' annually, consistent with the city's semi-arid climate. On average, 119 days of the year experience precipitation.[29]

| Climate data for Chelyabinsk | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 4.9 (40.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

34.9 (94.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

34.9 (94.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

39.9 (103.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −10.5 (13.1) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

25.2 (77.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

17.2 (63.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −14.9 (5.2) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −19.0 (−2.2) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −49.9 (−57.8) |

−44.9 (−48.8) |

−44.9 (−48.8) |

−29.9 (−21.8) |

−19.9 (−3.8) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−24.9 (−12.8) |

−39.9 (−39.8) |

−44.9 (−48.8) |

−49.9 (−57.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 17 (0.7) |

16 (0.6) |

19 (0.7) |

27 (1.1) |

47 (1.9) |

55 (2.2) |

87 (3.4) |

44 (1.7) |

41 (1.6) |

30 (1.2) |

26 (1.0) |

21 (0.8) |

430 (16.9) |

| Average rainy days | 0.1 | 0.3 | 4 | 10 | 15 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 114 |

| Average snowy days | 18 | 16 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 19 | 97 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85 | 77 | 76 | 66 | 61 | 64 | 69 | 71 | 73 | 73 | 82 | 83 | 73 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[30] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (precipitation days only)[31] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Architecture

The architecture of Chelyabinsk has been shaped through its history by the progression of historical eras in Russia. Before the 1917 Russian Revolution, the city was a trading center, with numerous merchant buildings in the eclectic and modern styles with elements of Russian Revival architecture, some of which are preserved on the pedestrian-only Kirovka Street.

Industrialization in Chelyabinsk started in the late 1920s. The construction of large plants was accompanied by the construction of new residential and public buildings in the constructivist style. Entire constructivist neighborhoods can be seen in the area of the Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant.[32]

In the late 1930s, a new era began in the city, with large-scale construction of Stalinist architecture. Many of the buildings in and around the city center and central avenue are constructed in this style.[33]

The next 60 years saw extensive construction of residential high-rise buildings as the city's population rose to about one million, notably within the large residential area called "Severo-Zapad" (English: North-West).

.jpg)

With the market reforms of the 1990s, there was an increase in the construction of office buildings and major shopping malls in postmodern and high-tech styles.

Parks and gardens

Chelyabinsk has seventeen public parks. The largest is Gagarin Central Park.[34] Its territory includes large areas of rocky and forested terrain, located around several now-flooded abandoned quarries.

Education

There are over a dozen universities in Chelyabinsk. The oldest, Chelyabinsk State Agroengineering Academy, was founded in 1930, followed by the Chelyabinsk State Pedagogical University in 1934. Major universities include South Ural State University, Chelyabinsk State University, South Ural State University of Arts, and Chelyabinsk Medical Academy. After World War II, Chelyabinsk became the main center of vocational education of the entire Ural region.[35]

Economy

Chelyabinsk is one of the major industrial centers of Russia. Heavy industries, especially metallurgy and military production, are predominant in the area, notably the Chelyabinsk Metallurgical Combinate (CMK, ChMK), owned by the mining corporation Mechel. Other important industries include Chelyabinsk Tractor Plant (CTZ, ChTZ), Chelyabinsk Electrode Plant (ChEZ), the machine part-producing Chelyabinsk Forge-and-Press Plant (ChKPZ), the crane-producing Chelyabinsk Mechanical Plant (ChMZ), and Chelyabinsk Tube Rolling Plant (ChTPZ), which is included in the "Big Eight" of pipe producers in Russia, and produces large-diameter pipes for use in pipelines. Chelyabinsk Zinc Plant, owned by the Ural Mining and Metallurgical Company, produces about 2% of the world's zinc supply and over 60% of the Russian supply. Kolyuschenko Road Machinery Plant produces construction machinery and dump trucks for the American manufacturer Terex.[36]

Molnija Watch Factory produces pocket watches, as well as technical watches for use in aircraft and ships. In 1980, Molnija watches were given as gifts to participants of the Moscow Olympic Games.[37]

The agro-industrial company Makfa, the largest producer of pasta in Russia, and one of the five largest producers in the world, is based in Chelyabinsk. The largest manufacturer of footwear in Russia, Unichel Footwear Firm, owns a factory in Chelyabinsk. Chelyabinsk is also home to the agricultural firm Ariant, which leads in the production of beverages and meat products in the Urals Federal District of Russia. The American corporation Emerson Electric owns part of the local company Metran, as well as a factory for the production of industrial equipment.[38]

In recent years, Chelyabinsk has had a significant role in other sectors of the Russian economy, hosting insurance firms, logistics centers, tourism, And important regional banking firms, such as Chelindbank and Chelyabinvestbank.

There are several large shopping malls. The largest of them are Gorky (English: Hills), built in 2007 with an area of 55,000 meters2, and Rodnik (English: Spring) built in 2011 with an area 135,000 meters2. At least two more are under construction: Almaz (English: Diamond), and Cloud, beginning construction in 2015 and 2018, with planned areas of 220,000 and 350,000 meters2, respectively.

Transportation

Public transport in Chelyabinsk consists of bus (since 1925), tram (since 1932) and trolleybus (since 1942) networks, as well as private marshrutka (routed cab) services. The city has several taxi companies.

In 2014 in Chelyabinsk began to run electric buses, trolleybuses fitted to run electrically.[39]

In 2011 the telecommunications company Beeline and Chelyabinsk city transport signed an agreement to provide passengers free internet. Currently Wi-Fi is available in some public trams and trolleybuses in Chelyabinsk.

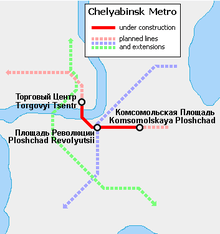

Chelyabinsk started the construction of a three-line subway network in 1992.[40]

The city is served by the Chelyabinsk Airport.

Sports

Several sports clubs are active in the city:

| Club | Sport | Founded | Current League | League Rank | Stadium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traktor Chelyabinsk | Ice Hockey | 1947 | Kontinental Hockey League | 1st | Traktor Arena |

| Chelmet Chelyabinsk | Ice Hockey | 1948 | Higher Hockey League | 2nd | Yunost Sports Palace |

| Belye Medvedi Chelyabinsk | Ice Hockey | 2009 | Junior Hockey League | Jr. 1st | Traktor Arena |

| FC Chelyabinsk | Football | 1977 | Russian Second Division | 3rd | Central Stadium |

| Sintur Chelyabinsk | Futsal | 1997 | Futsal Supreme League | 2nd | USURT Sports Complex |

| Dynamo-Metar Chelyabinsk | Volleyball | 1972 | Women's Volleyball Superleague | 1st | Metar-Sport Sports Palace |

| Dynamo Chelyabinsk | Volleyball | 1986 | Men's Volleyball Supreme League | 2nd | Metar-Sport Sports Palace |

In recent history, Chelyabinsk has hosted several important sporting events, especially in martial arts. These events include the 2012 European Judo Championships, the 2014 World Judo Championships, and the 2015 World Taekwondo Championships. 2015 also saw Chelyabinsk host the European Speed Skating Championships. In 2018, Chelyabinsk and nearby Magnitogorsk hosted the IIHF World U18 Championship.

Culture

The city has several libraries, notably Chelyabinsk Regional Universal Scientific Library, the largest public library in the Chelyabinsk Oblast. The library has more than 2 million books, over 12,000 of which are rare, originating from the 17th to 19th centuries.

Chelyabinsk is home to several theaters, which include the Nahum Orlov State Academic Drama Theatre, the Glinka State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre, Chelyabinsk State Chamber Theater, Chelyabinsk State Puppet Theater, Chelyabinsk State Youth Theatre, Mannequin Theater, Chelyabinsk New Arts Theatre, and Chelyabinsk Contemporary Dance Theatre.

There are nine museums in Chelyabinsk. Chelyabinsk Regional Museum was founded in 1913 and holds about 300,000 exhibits. Important expositions include the "Land of Cities" exhibit relating to the 2nd and 3rd millennium BCE settlement of Arkaim, the 570 kg largest fragment of the Chelyabinsk meteor, ornate 19th and 20th century blades made by Zlatoust arms factory, exhibits of Kasli artistic cast iron, and much more. Chelyabinsk Regional Picture Gallery has more than 11,000 works. The museum displays collections of Russian, European, and international works originating from the Middle Ages to modern times. The museum has significant collections of religious icons from the 16th to 20th centuries, along with early printed books and manuscripts. The Museum of History of the Southern Ural Railway hosts more than 30 exhibits of equipment used on the railway after its opening in Chelyabinsk in 1892.

The Museum of Military Equipment in the Garden of Victory was founded in 2007. It has 16 exhibits, including models of T-34 and IS-3 tanks, along with Katyusha rocket launchers produced in Chelyabinsk during World War II.

In addition, the city is home to the Chelyabinsk Regional Geological Museum, the Malgobekskii Museum of Military and Labor Glory, the Chelyabinsk Postal Service Museum, and the Entertaining Sciences Museum Eksperimentus.

Chelyabinsk Zoo is located in the central region of Chelyabinsk. It has an area of 30 hectares with more than 110 species of animals, of which more than 80 are listed in the Red Data Book of the Russian Federation. The zoo participates in international programs for the conservation of endangered species, including amur (siberian) tigers, far eastern leopards and polar bears. The zoo holds regular sightseeing tours, lectures, exhibitions and celebrations.

Other cultural attractions include the Chelyabinsk State Circus, the Chelyabinsk State Philarmonic Concert Hall named after Sergei Prokofiev, and Organ and Chamber Music Hall Rodina.

Chelyabinsk is home to several churches built from the 19th to 21st centuries.

Notable people

- Ariel, Soviet pop rock band

- Lera Auerbach (born 1973), composer and musician, born and grew up in Chelyabinsk

- Svyatoslav Belza (1942–2014), musical scholar, critic and essayist, born in Chelyabinsk

- Roman Albertovich Abalin, (NFKRZ) (born 1998), popular commentary youtuber, montage parody maker, rapper, born and started his career in Chelyabinsk

- Anatoliy Kroll (born 1943), jazz musician, bandleader, composer, born and started his career in Chelyabinsk

- Zhan Bush (born 1993), figure skater

- Yekaterina Gamova (born 1980), Olympic volleyball player, born and grew up in Chelyabinsk

- Makhmut Gareev (1923–2019), historian and military scientist, born and grew up in Chelyabinsk

- Viktor Khristenko (born 1957), politician, Minister of Industry of the Russian Federation, born and grew up in Chelyabinsk

- Igor Kurnosov (1985–2013), chess grandmaster, born in Chelyabinsk

- Oleg Mityaev (born 1956), singer-songwriter and actor, born, grew up, and came into prominence in Chelyabinsk

- Vadim Muntagirov (born 1990), ballet dancer, born in Chelyabinsk

- Staņislavs Olijars (born 1979), Latvian 110m hurdler, gold medallist at the 2006 European Athletics Championships, born in Chelyabinsk

- Georgy Ratner (1923–2001), surgeon, born in Chelyabinsk

- Nelli Rokita (born 1957), Polish politician, born in Chelyabinsk

- Eugene Roshal (born 1972), software developer, born in Chelyabinsk

- Mariya Savinova (born 1985), Olympic athlete, born in Chelyabinsk

- Galina Starovoytova (1946–1998), politician and human rights activist, born in Chelyabinsk

- Maksim Surayev (born 1972), cosmonaut, born in Chelyabinsk

- Evgeny Sveshnikov (born 1950), chess grandmaster and writer, born and grew up in Chelyabinsk

- Anna Trebunskaya (born 1980), ballroom and Latin dancer, born in Chelyabinsk

- Ivan Ukhov (born 1986), Olympic high jumper, born in Chelyabinsk

- Mikhail Yurevich (born 1969), businessman, politician, born in Chelyabinsk

- Mikhail Koklyaev (born 1978), Russian strongman competitor

Ice hockey players

- Sergei Babinov (born 1955), Soviet player, Canada Cup champion

- Vyacheslav Bykov (born 1960), Soviet player

- Stanislav Chistov (born 1983), NHL and KHL player

- Evgeny Davydov (born 1967), NHL player, USSR champion

- Sergei Gonchar (born 1974), NHL player, Stanley Cup champion

- Dmitri Kalinin (born 1980), NHL and KHL player, Gagarin Cup champion

- Alexandra Vafina (born 1990), Russian Olympic ice hockey player (2010, 2014)

- Evgeny Kuznetsov (born 1992), NHL and KHL player, Stanley Cup champion

- Sergei Makarov (born 1958), NHL player

- Andrei Nazarov (born 1974), NHL player and KHL coach

- Nikita Nesterov (born 1993), NHL and KHL player

- Valeri Nichushkin (born 1995), NHL and KHL player

- Valeri Karpov (1971–2014), Russian Superleague and NHL player

- Dmitri Tertyshny (1976–1999), Russian Superleague and NHL player

- Slava Voynov (born 1990), NHL player, Stanley Cup champion

- Danil Yerdakov (born 1989), KHL player

- Danis Zaripov (born 1981), KHL player, Gagarin Cup champion

- Yakov Trenin (born 1997), NHL player

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Chelyabinsk is twinned with:[41]

Diplomatic and consular missions and visa centers

See also

References

Notes

- Resolution #161

- "Chelyabinsk - Russia". Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "Челябинск сегодня – Визитная Карточка". Администрация г. Челябинска. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- "Information about central postal office" (in Russian). Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- "Russian Federation Cities dialing codes" (ZIP 34.4KB) (in Russian).

- "Investing in Chelyabinsk city". Invest in Russia. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- "Murzina" (PDF).

- "Invest in Ural". Invest in Ural. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- "Ancient Aryan civilization achieved incredible technological progress 40 centuries ago". Pravda.

- Basu, Dipak (2017). India as an Organization: Volume One. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-319-53372-8.

- Basu, Dipak (2017). India as an Organization: Volume One. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-319-53372-8.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 408–411.

- Basu, Dipak (2017). India as an Organization: Volume One. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-319-53372-8.

- "Челябинск: Ворота в Сибирь и Зауральский Чикаго". Портал Челябинская область.

- Campbell-Brown, Margaret. "What Do We Know about the Russian Meteor? Meteor researcher Margaret Campbell-Brown recaps the latest research into the cause of this morning's fireball over Chelyabinsk". Scientific American (Interview). Interviewed by John Matson. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

[Interviewer:] Where was most of the energy released as this object made its way through the atmosphere? [Subject:]In this case the final destination, which seems to have been the largest deposit of energy, was somewhere around 15 to 20 kilometers altitude. The actual fireball probably started significantly higher than that, maybe 50 kilometers, but most of the energy was apparently deposited during that last explosion lower in the atmosphere.

- "Meteorite hits Russian Urals: Fireball explosion wreaks havoc, up to 1,200 injured (PHOTOS, VIDEO)". RT. February 15, 2013.

- Plait, Phil (February 15, 2013). "Breaking: Huge Meteor Blazes Across Sky Over Russia; Sonic Boom Shatters Windows [UPDATED]". Slate. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- "Meteor strikes Earth in Russia's Urals". Pravda. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- "400 Injured by Meteorite Falls in Russian Urals". Associated Press. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- Agle, D. C. (February 13, 2013). "Russia Meteor not Linked to Asteroid Flyby". NASA news. NASA. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- Sreeja, VN (March 4, 2013). "New Asteroid '2013 EC' Similar To Russian Meteor To Pass Earth At A Distance Less Than Moon's Orbit". International Business Times. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- Yeomans, Don; Chodas, Paul (March 1, 2013). "Additional Details on the Large Fireball Event over Russia on Feb. 15, 2013". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- Law #706-ZO

- История Челябинска - от крепости до железнодорожной станции (in Russian). Портал Челябинская область.

- "Холмы Челябинска". Электронное периодическое издание Mediazavod.ru. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- "Chelyabinsk, Russia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- "Weather and Climate (Погода и Климат – Климат Челябинска)" (in Russian). Pogoda.ru.net. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- "World Weather Information Service – Cheljabinsk". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- Конструктивизм в архитектуре Челябинска (in Russian).

- "Сталинский ампир".

- "Парк Гагарина в Челябинске попал в топ-5 лучших в России".

- "На Урале".

- "В Челябинске начали производство 100-тонных самосвалов".

- "Часовой завод "Молния"". Archived from the original on July 11, 2014.

- "Вице-президент Emerson Process Management в Восточной Европе: "В Челябинске есть свой маленький центр «Сколково"".

- "В Челябинске начал курсировать электробус".

- "Chelyabinsk". UrbanRail.net. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- "Города-побратимы". cheladmin.ru (in Russian). Chelyabinsk. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- www.pinstudio.ru. "Филиалы - Visa Management Service". www.italyvms.ru. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- "La rete consolare". www.ambmosca.esteri.it. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

Sources

- Законодательное Собрание Челябинской области. Постановление №161 от 25 мая 2006 г. «Об утверждении перечня муниципальных образований (административно-территориальных единиц) Челябинской области и населённых пунктов, входящих в их состав», в ред. Постановления №2255 от 23 октября 2014 г. «О внесении изменений в перечень муниципальных образований (административно-территориальных единиц) Челябинской области и населённых пунктов, входящих в их состав». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Южноуральская панорама", №111–112, 14 июня 2006 г. (Legislative Assembly of Chelyabinsk Oblast. Resolution #161 of November 25, 2006 On Adoption of the Registry of the Municipal Formations (Administrative-Territorial Units) of Chelyabinsk Oblast and of the Inhabited Localities They Comprise, as amended by the Resolution #2255 of October 23, 2014 On Amending the Registry of the Municipal Formations (Administrative-Territorial Units) of Chelyabinsk Oblast and of the Inhabited Localities They Comprise. Effective as of the official publication date.).

- Законодательное Собрание Челябинской области. Закон №706-ЗО от 10 июня 2014 г. «О статусе и границах Челябинского городского округа и внутригородских районов в его составе». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Южноуральская панорама", №87 (спецвыпуск №24), 14 июня 2014 г. (Legislative Assembly of Chelyabinsk Oblast. Law #706-ZO of June 10, 2014 On the Status and Borders of Chelyabinsky Urban Okrug and the City Districts It Comprises. Effective as of the day of the official publication.).

- Anne Garrels, Putin Country: A Journey Into The Real Russia (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016).

- Lennart Samuelson, Tankograd: The Formation of a Soviet Company Town: Cheliabinsk, 1900s–1950s (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chelyabinsk. |

- Website about Chelyabinsk

- Chelyabinsk city portal (in Russian)

- Chelyabinsk News Agency (in Russian)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Interactive book about Chelyabinsk in iBooks Store

.jpg)