Charles L. Carpenter

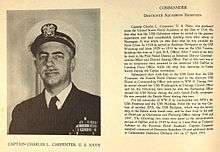

Rear Admiral Charles L. Carpenter (July 31, 1902 – February 21, 1992) was a Naval officer, holder of the Navy Cross, Purple Heart and whose career encompassed combat action in Nicaragua. He was involved in all three Theaters of Operations in World War II and naval combat in the Pacific. He commanded attack transports during the war and commanded an animal research vessel in the post-World War II era Operation Crossroads series of atomic bomb tests. He earned nine Service Bars, the U.S. Navy Combat Command Insignia, and foreign decorations from the governments of Nicaragua, Peru, and Spain.[1][2][3] Of his 30 years of active military service, 22 years were spent at sea or on foreign shores serving his Country.

Charles Lorain Carpenter | |

|---|---|

Rear Admiral Charles L. Carpenter | |

| Nickname(s) | "Charlie" |

| Born | July 31, 1902 Greensburg, Pennsylvania |

| Died | February 21, 1992 (aged 89) |

| Place of Burial | South Pine Grove Cemetery, South Waterboro, Maine |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1926–1956 |

| Rank | Rear Admiral |

| Commands held | USS Doran 1940 USS Freestone 1944–1945 USS Hocking, 1945–1946 USS Burleson 1946–1947 Commodore of Destroyer Squadron 18, 1952–1953 Naval Receiving Station, Brooklyn Navy Yard, 1953–1956 |

| Battles/wars | Second Nicaraguan Campaign World War II: Guadalcanal Campaign Battle of Cape Esperance Battle of Kula Gulf Okinawa Campaign |

| Awards | Navy Cross Purple Heart |

| Other work | Executive Director, Pennsylvania United Theological Seminary Foundation Genealogist |

Early life

Charles, also known as "Chuck" when younger and "Charlie" when older, was born July 31, 1902 in Greensburg, Pennsylvania.[2][3] He was the first son of Charles C. "Timothy" and Jennie Addell (Wilson) Carpenter. He was a direct descendant of William Carpenter the immigrant who came to America in 1635 from England and who settled in Providence, Rhode Island.[4] Carpenter received his early education in the public schools of Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, east of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He enjoyed running and track which he continued through his upper education. He was also a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon Fraternity.[1][5]

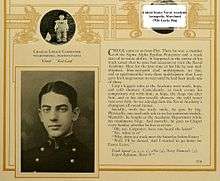

After graduating from high school, Carpenter attended the University of Pittsburgh until appointed to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1922.[1] While at PITT he studied mechanical engineering and participated in the US Army ROTC (Reserve Officers' Training Corps) program for two years. During the Spring of 1922, Carpenter received an appointment USNA (U.S. Naval Academy) from the Honorable M. Clyde Kelly, Congressional Representative of Pennsylvania's 30th congressional district. On June 16, 1922 he was sworn in and became a Plebe or freshman at the Academy.

On June 26, 1926 he graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland. He was commissioned an Ensign in the US Navy.[1][2][5][6]

US Navy career

Following his commissioning as an Ensign, Carpenter was deployed to serve in what was later called the Second Nicaraguan Campaign. He would serve on and later command US Navy ships and installations.[1]

USS Galveston – 1926

After graduating the US Naval Academy in June 1926, he was assigned to his first ship, USS Galveston, a Denver-class protected cruiser in the gunnery department.[7][n 1] Galveston was with the Special Service Squadron out of Christobal and Balboa, Panama. She conducted a series of patrols that took her off the coast of Honduras, Cuba, and Nicaragua under Gunboat diplomacy. On August 27, 1926 she arrived at Bluefields, Nicaragua, landing a force of 195 men at the request of the American Consul to protect American interests during a revolutionary uprising. Thereafter much of her time was spent cruising between that-port and Balboa to cooperate with the State Department in the restoration and preservation of order, and to insure the protection of American lives and property in Central America.

Carpenter participated in several landing force details including one at León, Nicaragua. It was at this time he was recognized and awarded the Navy Cross for his valor.[7]

His "extraordinary heroism, coolness and excellent judgment in the performance of duty" in the Leon detachment of the landing force on May 17, 1927 earned him the Navy Cross awarded by the President of the United States.[2]

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Ensign Charles Lorain Carpenter (NSN: 0-60331), United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism, coolness and excellent judgment in the performance of duty during an insurrection in Nicaragua. Ensign Carpenter was a member of the Leon detachment of the landing force and on 17 May 1927, while attempting to arrest and disarm an ex-rebel soldier after having been twice fired on, and at the time being surrounded by a crowd who egged on his aggressor, he in self defense shot and killed the soldier in question, thereby producing a most salutary effect on the population. His actions at all times were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. Action Date: 17-May-27 Service: Navy Rank: Ensign Division: Leon Detachment[2]

After returning to the States, Carpenter was stationed at the Boston Navy Yard and then assigned to duty in United States Pacific Fleet.[1][3]

USS Wyoming – 1928

In 1928 Ensign Charles "Chuck" Carpenter (Service Number 60331) served as the Assistant Navigator on USS Wyoming. She was the lead ship of her class of dreadnought battleships.[7]

In late August 1928, Wyoming went to Philadelphia for an extensive modernization. Her old coal-fired boilers were replaced with new oil-fired models and anti-torpedo bulges were added to improve her resistance to underwater damage. The work was completed by November 2, after which Wyoming conducted a shakedown cruise to Cuba the Virgin Islands. She was back in Philadelphia on December 7 and two days later, she returned to her post as the flagship of the Scouting Fleet, flying the flag of Vice Admiral Ashley Robertson.[n 2]

_at_the_Washington_Navy_Yard_on_29_September_1924_(npcc.26262).jpg)

USS Trenton – 1929

From 1929 to 1933 he was on USS Trenton. His last job on Trenton was as the 3 inch A.A. (anti-aircraft) officer.[7] While aboard Trenton in May 1929, the ship's division was detached from the Asiatic Fleet, and she steamed back to the United States along with Memphis and Milwaukee. The light cruiser was overhauled at Philadelphia in the latter part of 1929 and then rejoined the Scouting Fleet. For the next four years, Trenton resumed the Scouting Fleet schedule of winter maneuvers in the Caribbean followed by summer exercises off the New England coast. Periodically, however, she was ordered to the Isthmian coast to bolster the Special Service Squadron during periods of extreme political unrest in one or more of the republics of Central America. Carpenter left Trenton in the spring of 1933 before she moved to the Pacific and became flagship of the Battle Force cruisers.[n 3]

_on_21_August_1942.jpg)

Shore duty & USS Du Pont – 1933

In 1933 Carpenter was rotated from seven years at sea duty to shore duty as Assistant District Communications Officer and District Issuing Officer for the First Naval District then at Portsmouth Naval Yard.[7]

But Sergeant Fulgencio Batista and the 1933 Cuban "Revolt of the Sergeants" caused a sudden need for Landing Force Officers. Carpenter volunteered and went to sea on temporary duty on USS Du Pont which was a Wickes-class destroyer.[7] Du Pont was then in Rotating Reserve Squadron 19. She operated from Boston training Naval Reservists until assigned temporary duty on patrol off Cuba from September 1933 until February 1934. This was during the time Carpenter was on her.[n 4]

USS Gold Star – 1934

.jpg)

Going back to sea duty he served on USS Gold Star a civilian cargo ship purchased in 1922. During the 1920s and 1930s Gold Star became a familiar sight in the ports of Asia. Though assigned as flagship at Guam she made frequent voyages to Japan, China, and the Philippines with cargo and passengers. Prior to World War II, much of her crew was made up of Chamorro, natives of Guam with American non-commissioned officers and commissioned officers like Carpenter.[8] Strangely Carpenter's records of what he did on the "Gold Star" is absent from the spring of 1934 into early 1936.[n 5]

In 1934 Gold Star was a veteran Q-Ship dealing with communications intelligence as she moved from port to port and while in port. As a station ship she was assigned to monitor 1) Internal Japanese Fleet frequencies 2) Frequencies measurements and DF or direction finder azimuths. She had three intercept operators and one chief radioman supervised by an officer. This all started in 1933 during the reconstruction of the Japanese fleet by Tokyo. Gold Star along with ground stations at Guam, Olongapo and Beijing provided significant intelligence before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.[9]

As a side note – Carpenter had married Dorothy Gertrude Hanna on August 8, 1931 and had a child, Charles Lorain Carpenter, Jr. on August 31, 1934. His wife "Dottie" had the unique experience of sailing in Gold Star with her husband and their infant son – who was named "Skipper" while on board the ship. The ship, with Carpenter's new family, conducted seven loops of about seven weeks each around the Orient. Some of the other officers and senior Petty Officers were permitted to have their families with them for much shorter times when the ship sailed from Guam. It appears that the Carpenter family received the most benefit from this unique window dressing distraction. It is unknown if Carpenter's wife was ever aware that while the ship visited various ports like in Japan like Miki-Ko, Nagasaki, Kobe, Nagoya, and Yokohama that part of the ship was spying on the Japanese.[4]

USS Tennessee – 1936

Carpenter was then assigned to USS Tennessee in 1936 during Panama Fleet maneuvers. Then he was assigned to shore duty with the Fourth Naval District headquartered at League Island Navy Yard in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[7] Again his duties are not given.[n 6]

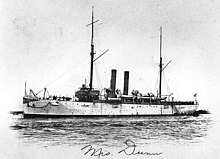

USS Doran – 1940

Carpenter was assigned to the newly renamed Wickes-class destroyer USS Doran as its commanding officer in early 1940.[7][n 7] She had been named Bagley but decommissioned on July 12, 1922. She served on loan from 1932 to 1934 with the United States Coast Guard. Her name was dropped on May 31, 1935 allowing the US Navy to reuse the name for a new ship by the same name Bagley, a Bagley-class destroyer commissioned in 1936. From 1935 to late 1939 the ex-Bagley was referred to as DD-185 (ex-Bagley). The start of World War II and the Royal Navy's dire need for destroyers saved her from the shipbreakers. She was refurbished at Philadelphia. DD-185 was renamed Doran on December 22, 1939.[n 8]

._Port_bow%2C_05-29-1941_-_NARA_-_513042.jpg)

Carpenter worked on readying Doran for sea duty and the ship was recommissioned on June 17, 1940. Doran reported to the Atlantic Squadron. They served with the Squadron until September 22, 1940, when she was decommissioned from the US Navy at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and transferred in the destroyer-land bases exchange to Great Britain to serve in the Royal Navy as HMS St. Mary's, a Town-class destroyer.[n 7]

USS Washington – 1941

In 1941 he was on USS Washington, a North Carolina-class battleship as its Damage Control Officer.[7] Washington was commissioned on May 15, 1941 and assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. Because of major problems with acute longitudinal vibrations from her propeller shafts delayed full power tests until August 3, 1941. Repairs greatly reduced the vibrations by adding new propeller combinations. This greatly reduced tanks, pipes, and other equipment breakages that kept Carpenter and other damage control personnel busy.[10][n 9]

On December 7, 1941 Carpenter was on Washington. In early 1942 US Navy reassignments were made. Carpenter went from the Atlantic to the United States Pacific Fleet for war duty.[10]

World War II

_off_the_Mare_Island_Naval_Shipyard_on_1_July_1942_(NH_95813).jpg)

USS Helena

Carpenter was the navigator on USS Helena, a St. Louis-class light cruiser, when she sailed to enter action during the Guadalcanal Campaign in 1942.[7][n 10] He was third in command of the ship. They escorted a detachment of Seabees and an aircraft carrier rushing planes to the South Pacific. She made two quick dashes from Espiritu Santo to Guadalcanal, where the long and bloody battle for the island was then beginning, and having completed these missions, joined the task force formed around the aircraft carrier Wasp. This task force steamed in distant support of six transports carrying Marine reinforcements to Guadalcanal. Mid-afternoon on 15 September 1942, Wasp was suddenly hit by three Japanese torpedoes. Almost at once, she became an inferno. Helena stood by to rescue nearly 400 of Wasp's crew, whom she took to Espiritu Santo.[n 10]

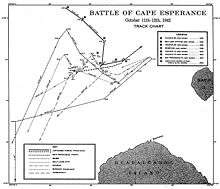

Helena's next action was near Rennell Island, again in support of a movement of transports into Guadalcanal. During the Battle of Cape Esperance in October 1942, Carpenter navigated the Helena into combat to protect the transports carrying the 2,837 men of the 164th Infantry Regiment to Guadalcanal, Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley—overall commander of Allied forces in the South Pacific- ordered Task Force 64 (TF 64), consisting of four cruisers (San Francisco, Boise, Salt Lake City, and Helena) and five destroyers (Farenholt, Duncan, Buchanan, McCalla, and Laffey) under U.S. Rear Admiral Norman Scott, to intercept and combat any Japanese ships approaching Guadalcanal and threatening the convoy. Scott conducted one night battle practice with his ships on 8 October, then took station south of Guadalcanal near Rennell Island on 9 October, to await word of any Japanese naval movement toward the southern Solomons.[11]

Carpenter was on the bridge during this confused night battle where he assisted plotting radar sightings. Helena's radar showed the Japanese warships to be about 27,700 yd (25,300 m) away. Between 23:42 and 23:44, Helena and Boise reported their contacts to Scott on San Francisco who mistakenly believed that the two cruisers were actually tracking the three U.S. destroyers that were thrown out of formation during the column turn. Scott radioed Farenholt to ask if the destroyer was attempting to resume its station at the front of the column. Farenholt replied, "Affirmative, coming up on your starboard side," further confirming Scott's belief that the radar contacts were his own destroyers.[12]

Lookouts on the Helena reported Helena's and Salt Lake City's lookouts. The U.S. formation at this point was in position to cross the T of the Japanese formation, giving Scott's ships a significant tactical advantage. At 23:46, still assuming that Scott was aware of the rapidly approaching Japanese warships, Helena radioed for permission to open fire, using the general procedure request, "Interrogatory Roger" (meaning, basically, "Are we clear to act?"). Scott answered with, "Roger", only meaning that the message was received, not that he was confirming the request to act. Upon receipt of Scott's "Roger", Helena—thinking they now had permission—opened fire, quickly followed by Boise, Salt Lake City, and to Scott's further surprise, San Francisco.[13] The Japanese force was taken almost completely by surprise.

A junior officer on Helena later wrote, "Cape Esperance was a three-sided battle in which chance was the major winner."[14] Helena was next under attack on the night of 20 October while patrolling between Espiritu Santo and San Cristobal. Several torpedoes passed near her but she was not hit. Carpenter, who had had special instruction on torpedo avoidance, was teaching others well.

In November 1942, Carpenter and Helena saw combat during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal from its beginning when they were assigned the job of escorting a supply echelon from Espiritu Santo to Guadalcanal. The ship made rendezvous with the convoy of transports off San Cristobal on 11 November, and brought it safely into Guadalcanal. During the afternoon of 12 November, word came from a coast watcher, "enemy aircraft approaching." Immediately suspending unloading operations, all ships stood out to form an antiaircraft disposition. When the attack came, superb maneuvering of the force, and its own antiaircraft fire, broke up the first attack, but the second damaged two ships. Helena came through without a scratch, and the task group brought down eight enemy planes in the eight-minute action.[15]

In the early morning at 0124 hours on the night of 13 November, Helena's radar first located the enemy from the rear center of the allied single column of ships just behind Portland. Despite Carpenter's effort in plotting the enemy's course on radar, they had trouble communicating the information to Callaghan because of his inexperience operating the ships as a cohesive naval unit. There was no modern Command Information Center (CIC) communicating information seen by radar was still new. Add problems with their radio equipment and a further lack of discipline regarding their communications procedures.[16] Another message was sent and received but it did not reach the Callaghan in time to process and use given his ignorance of radar and an appreciation of its accuracy—especially the reliability of ranges and bearings so obtained—along with the lack of practice coordinating radar information to visual data.[15]

The U.S. ship formation began to fall apart, apparently further delaying Callaghan's order to commence firing as he first tried to ascertain and align his ships' locations.[17] Meanwhile, both forces' formations began to intermingle with each other as the individual ship commanders on both sides anxiously awaited permission to open fire. Navigators like Carpenter struggled to retain positioning of their ship within the resulting melee.[15][18]

At 01:48, Akatsuki and Hiei turned on large searchlights and lit up Atlanta only 3,000 yd (2,700 m) away—almost point-blank range for large naval artillery. Several of the ships on both sides spontaneously opened fire. Realizing that his force was almost surrounded by Japanese ships, Callaghan issued the confusing order: "Odd ships fire to starboard, even ships fire to port"[15][18] (save that no pre-battle planning had assigned any such identity numbers to reference, and the formation was already chaotic).[15] Most of the remaining U.S. ships, including the Helena, then opened fire, although several had to quickly change their targets in order to comply with Callaghan's order.[19] As the ships from the two sides intermingled, they battled each other in an utterly confused and chaotic mêlée at close distances where the superior Japanese optics and well practiced Japanese drill at optically sighted night aiming proved to be deadly effective. Afterward, an officer on Monssen likened it to "a barroom brawl after the lights had been shot out".[20]

At least six of the U.S. ships—including Helena fired at Akatsuki, which drew attention to herself with her illuminated searchlight. Akatsuki was hit repeatedly and blew up and sank within a few minutes.[21]

During the almost post blank melee and unable to fire her main or secondary batteries at the three US destroyers causing her so much trouble, the Japanese ship Hiei instead concentrated on San Francisco which was passing by only 2,500 yd (2,300 m) away.[22] Along with Kirishima, Inazuma, and Ikazuchi, the four ships made repeated hits on San Francisco, disabling her steering control and killing Admiral Callaghan, Captain Cassin Young, and most of the bridge staff. The first few salvos from Hiei and Kirishima consisted of the special fragmentation bombardment shells, which reduced damage to the interior of San Francisco and may have saved her from being sunk outright. Not expecting a ship-to-ship confrontation, it took the crews of the two Imperial battleships several minutes to switch to armor-piercing ammunition. Nevertheless, San Francisco, almost helpless to defend herself, managed to momentarily sail clear of the melee.[23] However, she landed at least one shell in Hiei's steering gear room during the exchange, flooding it with water, shorting out her power steering generators, and severely inhibiting Hiei's steering capability.[24] Helena followed San Francisco to try to protect her from further harm.[25]

The enemy Amatsukaze approached San Francisco with the intention of finishing her off. However, while concentrating on San Francisco, Amatsukaze did not notice the approach of Helena which fired several full broadsides at Amatsukaze from close range and knocked her out of the action. The heavily damaged Amatsukaze escaped under cover of a smoke screen while Helena was distracted by an attack by Asagumo, Murasame, and Samidare.[26][27]

After nearly 40 minutes of the brutal, close-quarters fighting, the two sides broke contact and ceased fire at 02:26 after Abe and Captain Gilbert Hoover (the captain of Helena and senior surviving U.S. officer at this point) ordered their respective forces to disengage.[28] Admiral Abe had one battleship (Kirishima), one light cruiser (Nagara), and four destroyers (Asagumo, Teruzuki, Yukikaze, and Harusame) with only light damage and four destroyers (Inazuma, Ikazuchi, Murasame, and Samidare) with moderate damage. The U.S. had only one light cruiser (Helena) and one destroyer (Fletcher) that were still capable of effective resistance. Although perhaps unclear to Abe, the way was clear for him to bombard Henderson Field and finish off the U.S. naval forces in the area, clearing the way for the troops and supplies to be landed safely on Guadalcanal. However, at this crucial juncture, the Japanese commander chose to abandon the mission and depart the area. Helena and other US ships had turned back the enemy and prevented the heavy attack that would have been disastrous to the Marine troops ashore.[29]

The US ships Portland, San Francisco, Aaron Ward, and Sterett were eventually able to make it back to rear-area ports for repairs. Atlanta, however, sank near Guadalcanal at 20:00 on 13 November.[30] Departing from the Solomon Islands area with San Francisco, Helena, Sterret, and O'Bannon later that day, Juneau was torpedoed and sunk by Japanese submarine I-26.[31]

The captain of Helena, now the senior American officer in the task force because of the death of the task force commander Callaghan in action, Helena's skipper — Captain Gilbert Hoover — commanded the task force's retirement to Espiritu Santo from the battle area. While he focused on this new duty, Carpenter commanded the bridge of Helena. On the way, light cruiser Juneau was torpedoed and sunk by submarine. Despite observed survivors, Captain Hoover assessed that the task force lacked the means to conduct a search and rescue in its current location and condition, the battle leaving two ships with antisubmarine capacity on hand (one heavily damaged) and other ships too damaged to remain in the area.[31]

Juneau's 100+ survivors (out of a total complement of 697) were left to fend on their own in the open ocean for eight days before rescue aircraft belatedly arrived. While awaiting rescue, all but ten of Juneau's crew died from their injuries, the elements, or shark attacks. The dead included the five Sullivan brothers. For this inaction of rescue, Halsey removed Hoover from command of Helena, which he later regretted as a grievous mistake, writing in his memoirs that "Hoover's decision was in the best interests of victory".[31]

_at_the_Mare_Island_Naval_Shipyard%2C_circa_in_July_1942.jpg)

Helmsman view

From the memoirs of George Albert DeLong, helmsman of USS Helena when USS Juneau was sunk.[32]

My assignment was on the bridge in the pilot house as helmsman. While steering the ship I had the opportunity to glance out the portholes and I saw the condition of the San Francisco and the Juneau. I remember commenting to one of the men in the pilot house that the San Francisco looked so beat up that she would be lucky to make it back to Espiritu Santo, but that the Juneau, while she was down by the bow, still looked seaworthy enough to make it back

Shortly thereafter, however, Lt. Comdr. Carpenter, the ship's navigator, who seldom left the bridge, shouted, "Hard right rudder, DeLong." I spun the rudder over hard right and started singing out the course changes every ten degrees. I glanced out the porthole as the bow swung past the line of sight to the Juneau who had been on our starboard quarter in the formation. The ship was swinging at a rapid speed now and I had no idea what was going on.

Suddenly, Comdr. Carpenter hollered, "Hard left rudder." I reversed the rudder, but the momentum was still carrying the ship to the right. The ship shuddered for several seconds and slowly started to turn left when an immense explosion took place. I glanced out the porthole and all I could see was a huge cloud in the direction the Juneau had been.

By this time the Helena was making good time through the water again and picking up momentum heading straight for the cloud. The wheel was still turned hard left and I had no idea where either the Juneau or the San Francisco were. Total silence reigned in the pilot house and on the wings of the bridge.

Now it was my turn to shout! "Where is she? Where is she? Where is she? I don't want to ram her!" Everyone was out on the wing of the bridge except me and no one other than myself was talking.

Finally, one of the sailors stuck his head in the door and quietly said, "DeLong, she ain't no more." I didn't fully understand what he meant but I decided to ease the rudder lest it bang against the stops and get stuck. I was a little late but in time enough to keep the rudder from jamming. There was a jolt as the rudder hit the stop, but it was light enough so there was no jamming.

The people that had gone outside now filled me in with what had happened. The Juneau didn't sink; she was blown up. Everyone had seen pieces of her flying through the sky. The largest piece was reported as one of her five inch gun mounts flying over the Helena.

Captain Hoover wisely decided to save all the ships he could and decided not to stop to look for survivors – no one thought there would be any. Even if there were, the subs might still be around and more ships and men could be lost.

As a footnote to this event, many years later, I ran across Lt. Comdr. Carpenter (by that time Admiral Carpenter) at a Helena reunion and he filled in some details that I hadn't known. We were seated across from each other at a dinner table. We were all telling sea stories and I started telling them my story (I had forgotten that it was Commander Carpenter who had issued the orders to the wheel). Right in the middle of my story Carpenter looked at me and said, "And do you know who issued those orders?" When I admitted that I didn't remember, but wished that I could, he replies, "I did." The minute he said that, I remembered.

From that point on he took over the story. He told us that in the early part of his career he had taken special training on spotting and tracing torpedo wakes and that was one of the reasons he felt a little safer when he was on the bridge in treacherous waters. As a result of his early training he was the first one to see the wakes of the two torpedoes coming from the port side. Both torpedoes went between the Helena and the San Francisco and when both ships turned, the torpedoes went past us and one of them hit the Juneau. We were not able to warn the Juneau in time to save her.

George A. DeLong

Sinking of Helena

Helena was later assigned to the several bombardments of Japanese positions on New Georgia in January 1943. One of Carpenter's shipmates, Lt. Bin "Red" Cochran[e], commanding the aft 5-inch battery on Helena, shot down a Japanese Aichi D3A Val dive-bomber with the second of three salvos of VT-fuzed shells, near Guadalcanal. The fuzes were manufactured by the Crosley Corporation and this was their first kill of an enemy aircraft. Helena's guns rocked the enemy at Munda and Vila Stanmore, leveling supply concentrations and gun emplacements. Continuing on patrol and escort in support of the Guadalcanal operation through February, one of her floatplanes shared in the sinking of the submarine Ro-102 on 11 February. After overhaul in Sydney, Australia, and a brief leave, Carpenter was back on Helena headed to Espiritu Santo in March to participate in bombardments of New Georgia Island, soon to be invaded.[33]

_firing_during_the_Battle_of_Kula_Gulf%2C_6_July_1943_(80-G-54553).jpg)

On 4 July 1943, Carpenter navigated Helena into the Kula Gulf just before midnight. Shortly after midnight on the 5th, her guns opened up in what was to be her last shore bombardment. The landing of troops was completed successfully by dawn, but during the afternoon of 5 July, word came that the Tokyo Express was ready to roar down once more and the escort group turned north to meet it. By midnight on 5 July, Helena's group was off the northwest corner of New Georgia, three cruisers and four destroyers composing the group. Racing down to face them were three groups of Japanese destroyers, a total of 10 enemy ships. Four of them peeled off to accomplish their mission of landing troops. By 01:57, the Battle of Kula Gulf had begun, Helena began blasting away with a fire so rapid and intense that the Japanese later announced in all solemnity that she must have been armed with "6 inch machine guns". The gunners fired 2,000 six-inch rounds and 400 smaller rounds during the battle. Ironically, Helena made a perfect target when lit by the flashes of her own guns, which was compounded by the fact that Helena had fired all her flashless powder in the preceding bombardments and was left with standard smokeless powder, which produced immense flames when fired.[34]

Captain Cecil had positioned himself on the "fighting bridge" an open air command area. This was just below the forward main battery directors in an area that protruded a bit giving him panoramic observation of events. Directly below Cecil's position was the enclosed pilot house where Commander Carpenter stood overseeing operations there. Communications were done by a voice tube.[33] Before Helena opened fire to port at 0157 hours, Carpenter and the rest of the crew were at their battle stations. About seven minutes after she opened fire at about 0203 hours, Helena was hit by a torpedo. The first enemy Type 93 torpedo, also called a Long Lance, could travel at 48–50 knots (89–93 km/h; 55–58 mph) and impacted Helena on the port side just below number one turret (near frame 32) tearing off the bow of the ship. As the tall column of water thrown up by the explosion began to fall, the ship staggered then began to surge ahead as the bow sheared off to starboard.[33][34]

Further explosions by two more torpedoes that hit under the second stack, port side (near frame 82 and about frame 85) less than two minutes later at about 0205 caused catastrophic and terminal damage. Men were thrown about twice with each following explosion and the force was greater the higher up in the ship's structure. This is the time that Carpenter was injured. The forward movement of the ship along with the massive structural frame damage caused the ship to twist and jackknife around the damaged area. The ship's momentum quickly fell off and began to flood. The center part twisted to 45 degrees port sinking first. It dragged the rear of the ship down until the stern was vertical. Men quickly realized that the damage was fatal and began to abandon ship. About 22 minutes after the ship was first hit the ship sunk, at about 0225. In the meantime, Carpenter – who had been wounded in the legs – and others of the crew abandoned ship by going over the side after cutting free all the surviving lift rafts into the ocean. Even though the forward momentum of the ship dropped off rapidly the survivors were scattered over several hundred yards, at night, amidst a raging naval battle. Later currents would separate them even more.[33][34]

In the dark night the bow of Helena floated for some time with the ship number 50 showing. It became a lifeboat of sorts, until friendly forces not knowing what it was almost fired at it. But USS Radford illuminated the unknown object and identified it as a ship's prow. Finally the destroyer put a searchlight on the floating wreckage and it was identified as the remains of Helena. The bow would sink later the next day.[33][34]

_in_the_Battle_of_Kuly_Gulf%2C_6_July_1943_(C_l5001).jpg)

Rescue of the crew

_survivors_being_greeted_by_Admiral_Ainsworth%2C_7_July_1943.jpg)

Helena's history closes with the almost incredible story of what happened to her men in the hours and days that followed.[33]

Within 30 minutes two destroyers, Nicholas and Radford were picking up survivors of Helena. This included the wounded Carpenter who had taken charge of several rafts. While many of the cruiser's survivors were picked up before morning, many were not saved until 11 days later.[33]

At daylight approached, the enemy was in range once more, and again destroyers Nicholas and Radford broke off their rescue operations to pursue. Anticipating an air attack, the destroyers withdrew for Tulagi, carrying with them all but about 275 of the survivors.[33]

To those who remained they left four boats, manned by volunteers from the destroyers' crews collected those in still in the water. Captain Charles Purcell Cecil, Helena's commanding officer, organized a small flotilla of three motor whaleboats, each towing a life raft, carrying 88 men to a small island about 7 miles from Rice Anchorage after a laborious all-day passage. This group was rescued the next morning by destroyers Gwin and Woodworth.[33]

For the second group of nearly 200, the bow of Helena was their life raft, but it was slowly sinking. Disaster was staved off by a Navy PB4Y-1 (B-24) Liberator that dropped lifejackets and four rubber lifeboats. The wounded were placed aboard the lifeboats, while the able-bodied surrounded the boats and did their best to propel themselves toward nearby Kolombangara. But wind and current carried them ever further into enemy waters. Through the torturous day that followed, many of the wounded died. American search planes missed the tragic little fleet, and Kolombangara gradually faded away to leeward. Another night passed, and in the morning the island of Vella Lavella loomed ahead. It seemed the last chance for Helena's men and so they headed for it. By dawn, survivors in all three remaining boats observed land 1 nmi (1.2 mi; 1.9 km) distant and all who were left were safely landed. Two coastwatchers and loyal natives cared for the survivors as best they could, and radioed news of them to Guadalcanal. The 165 remaining crew of Helena then took to the jungle to evade Japanese patrols.[33][34]

Surface vessels were chosen for the final rescue, Nicholas and Radford, augmented by Jenkins and O'Bannon set off on 15 July to sail further up the Slot than ever before, screening the movement of two destroyer-transports and four other destroyers. During the night of 16 July, the rescue force brought out the 165 Helena men, along with 16 Chinese who had been in hiding on the island. Of Helena's nearly 900 men, 168 had perished. Later during the investigation of the sinking, Carpenter and other survivors were commended for their actions.[33][34]

USS Freestone

Carpenter was promoted to captain in August 3, 1944. After leave and some training he was sent to command a brand new attack transport called USS Freestone a Haskell-class ship.[1][3][n 11]

The following in a condensed format reflects Carpenter's actions on USS Freestone. It is from the official history of USS Freestone written in 1946.[35]

On November 8, 1944 the official Navy acceptance board to accept USS Freestone invited the prospective commanding officer, Captain Charles L. Carpenter, USN to attend the river and acceptance runs. The ship passed its testing and was recommended for acceptance by the Navy. The docked at "starboard side to Pier #3, U.S. Naval Station, Astoria, Oregon. At 0930 the next day the ship was placed into commission. Captain Carpenter assumed command and ordered the watch set. On November 20, the ship set out to sea conducting training and drills to prepare for war service. On January 8, 1945 the ship sailed from San Diego to embark 1471 troops en route to Saipan, Marinas Islands. The small task force, Task Unit 96.3.18 with Captain Carpenter commanding arrived February 6 and debarked the troops.[35]

On February 28, 1945 the ship arrived in Leyte Gulf in the Philippine Islands where they were alerted to Japanese air attacks. After more training, Carpenter and his ship loaded members of the 184th Infantry and a Regimental Combat Team and were assigned to Task Force 51 for the invasion of Okinawa. They arrived there on April 1 and within seven days completed their mission debarking their troops and supplies. During several Japanese air raids and Kamikaze attacks the Freestone was credited with one enemy aircraft shot down.[35]

The ship's medical department received battle casualties and the majority of those departed with the ship and were taken to the hospital in Guam. Carpenter then took his ship, under orders, back to the West Coast of the United States then back to the Philippines transporting personnel and supplies. During dry dock repairs and alterations to prepare for the invasion of mainland Japan, the ship received word of the Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. Work was suspended for two days for the celebration of VJ Day (Victory over Japan Day).[35]

Captain Carpenter took his ship to Nagasaki, Japan to deliver occupation troops. Later they were assigned to Operation Magic Carpet and began shuttle runs back to the United States for troops being sent home. On November 10, 1945, Carpenter was reassigned and said goodbye to the officers and crew of USS Freestone.[35]

Post war

For his service during the war, Carpenter was awarded a number of medals and citations, including the Purple Heart for wounds received in combat during the Battle of Kula Gulf.[1] He became a member of the Naval Order of the United States.[36]

USS Hocking

Carpenter was assigned to command the attack transport USS Hocking in December 1945. She was his second Haskell-class attack transport.[1][7]

Hocking arrived, from the Asiatic, at San Pedro December 5, 1945, and under Carpenter subsequently made another voyage to Guam and the Philippines bringing home veterans. Carpenter left the Hocking in February 1946 as she was scheduled to go into the reserves. She left San Pedro on March 1, 1946 and was returned to the Maritime Commission via the Canal Zone to Norfolk, Virginia, where she decommissioned May 10, 1946. Hocking joined the National Defense Reserve Fleet and was berthed in the James River, near Norfolk on May 22, 1946. In 1974 she was scrapped.[n 12]

Shore duty

He left Hocking in February 1946 in the Canal Zone for assignment at the Naval District 12 in San Francisco, California.[1][7]

_at_Little_Creek_in_1951.jpg)

USS Burleson

Carpenter then became the captain of USS Burleson, a Gilliam-class attack transport. The ship was modified as an animal research vessel in Task Group 1.1 commanded by Rear Admiral William Sterling Parsons for the Operation Crossroads series of atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll.[1][37]

In June 1946, Burleson moved from Pearl Harbor to Bikini carrying animals to be used in the two nuclear tests. She was not a target vessel, but a support ship. Carpenter and his ship observed both tests and moved into the test area after each to remove the animals for study. The surviving animals were observed closely and a better understanding of radioactivity was achieved.[37]

At the end of the summer of 1946, Burleson sailed to the East Coast of the United States. She reported for duty at the Naval Amphibious Base, Little Creek, Virginia, where she was decommissioned on November 9, 1946. In 1968 she was scrapped.[n 13]

PhibLant & OpNav

Captain Carpenter was back ashore with Amphibious Forces, Atlantic Fleet (PHIBLANT) under the command of Commander, Naval Surface Forces Atlantic in 1947. Part of his job was to conduct a review of amphibious landings previous conducted. He continued his work at OpNav for the Chief of Naval Operations then Admiral Louis E. Denfeld until August 1949. These were administrative duties in preparation for future duties.[7]

Carpenter was present during the Revolt of the Admirals which was an episode that took place in 1949. This was when several United States Navy admirals, headed by Admiral Denfield, publicly disagreed with the President Harry S. Truman and the Secretary of Defense's plans for the reduction of the Navy and their new emphasis on the strategic nuclear bombing role by the Air Force as the primary means by which the nation was defended. This incident occurred during the early post war period, before the conflict in Korea and when the technologies of large jet aircraft, the nuclear bomb and the means by which it could be delivered were in a developmental stages.

The debate climaxed during the House Armed Services Committee investigation into the inter-service rivalry held in August 1949 and focused on the allegations of fraud and corruption emanating from the "Worth Paper".[38] The committee found no substance to charges relating to the role of the Secretary of the Air Force Stuart Symington in aircraft procurement.[39] This resulted in a vindication for Secretary Johnson and embarrassment for the Navy.[40] More committees and firings continued including Denfield. At one point even the question of a future US Navy was in doubt.

The Truman administration essentially won the conflict with the Navy, and civilian control over the military was reaffirmed. Military budgets following the hearings prioritized the development of Air Force heavy bomber designs, accumulating a combat ready force of over one thousand long range strategic bombers capable of supporting nuclear mission scenarios. These were deployed across the country and at overseas bases. The Air Force portion of the total defense budget grew, while the Navy's portion of the defense budget was significantly reduced.[41]

The wisdom of the Air Force position and the Truman administration's national doctrine was soon put to the test. Within six months, 25 June 1950, the Korean War broke out and the U.S. was forced to confront an invading army with the forces it had on hand.[42] By this time Carpenter was in Lima, Peru at the Peruvian Naval Academy as a Technical Advisor and away from any possible career terminations.[7]

Later career

By 1951 Carpenter was stationed at Naval Headquarters in Washington D.C., and as of April 17, 1952 he served as Commodore (United States) of Destroyer Squadron 18 and additional duties as Commander of Destroyer Division 181[7] in the Mediterranean in 1952.[1]

His final assignment before retiring from the Navy in 1956 was commander of the Naval Receiving Station at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.[1]

Post career

After leaving the Navy, Carpenter moved to Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania, and became the executive director of the Pennsylvania United Theological Seminary Foundation, serving as its chief fund-raiser until the early 1960s.[1][3]

Memorial Chair Seat 18 in row 22 of section 2 at the Navy-Marine Corps Memorial Stadium in Annapolis, Maryland was named in his honor thanks to his wife "Dottie."[4]

Carpenter was a member of numerous Masonic and Military orders, the Sigma Alpha Epsilon National Collegiate Fraternity at Pitt, the New York Yacht Club, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and Waterboro, Maine and a communicant of the Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania United Methodist Church.[1]

He also became interested in genealogy and traveled doing extensive research. In 1976 he published a book on The Descendants of Timothy Carpenter (1715–1787) of Pittstown, Rensselaer County, New York.[4]

In 1978 he moved to Lima, Pennsylvania, in Delaware County. There he wrote several genealogical related articles and completed a draft of a large 813 page The Descendants of William Carpenter (of) Rehoboth, Bristol County, Massachusetts. This work was published in 2002 by his grandson Chad Carpenter.[4]

Carpenter's wife "Dottie" died on April 25, 1973 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and she was buried in South Pine Grove Cemetery in South Waterboro, Maine.'[4] "Charlie" died also in Philadelphia on February 21, 1992. He was interred next to his wife. He was survived by his son, Charles L. Carpenter, Jr., a retired major of the U.S. Marines; daughter, Olivia Salzberg, and six grandchildren.[1][2]

Military Awards and Decorations

US Navy Command at Sea Insignia |

||

| Navy Cross | ||

| Purple Heart | Navy Unit Commendation | 2nd Nicaraguan Campaign Medal |

| China Service Medal | American Defense Service Medal(Fleet Clasp) | American Campaign Medal |

| European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with 3 Campaign stars | World War II Victory Medal |

| Navy Occupation Service Medal (Asia) | National Defense Service Medal | Philippine Liberation Medal |

| Peruvian Navy Cross | Nicaraguan Presidential Medal of Merit w/ Silver Star | Cross of Naval Merit (Spain) |

| Combat Command Insignia | ||

Ranks Held

| Rear Admiral |

|---|

| O-7 |

|

| January 12, 1956 |

| Captain | Commander | Lieutenant Commander | Lieutenant | Lieutenant j.g. | Ensign |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-6 | O-5 | O-4 | O-3 | O-2 | O-1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| August 1/3, 1943 | August 15, 1942 | July 1, 1941 | June 30, 1936 | June 3, 1929 | June 26, 1926 |

Ships served on

- USS Galveston (CL-19), 1926–1927, Gunnery Department, with shore duty in Nicaragua

- USS Wyoming (BB-32), 1928, Assistant Navigator

- USS Trenton (CL-11), 1929–1933, Anti-Aircraft Officer

- USS DuPont (DD-152), 1933–1934, Landing Force Officer, on patrol off Cuba

- USS Gold Star (AK-12)

- USS Tennessee (BB-43)

- USS Doran (DD-634), Commanding Officer

- USS Washington (BB-56), 1941, Damage Control Officer

- USS Helena (CL-50), 1942–1943, Navigating Officer

- USS Freestone (APA-167), 1943–1944, Commanding Officer

- USS Hocking (APA-121), 1944–1945, Commanding Officer

- USS Burleson (APA-67), 1946, Commanding Officer

Video

- Video of USS Helena survivors at the funeral of Irwin Edwards, who succumbed to his wounds after being rescued. Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth, with cap, shakes the hands of the survivors. This includes Commander Charles L. Carpenter, with mustache, senior rescued officer. Aboard the USS Honolulu, dated 7 Jul 1943.

- Commander Charles L. Carpenter, center with mustache, at the head of the gangplank as USS Helena survivors are transferred to another ship. Dated 7 Jul 1943.

See also

Ship notes

DANFS references reflect Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships histories.

- DANFS USS Galveston

- DANFS USS Wyoming

- DANFS USS Trenton

- DANFS USS Du Pont

- DANFS USS Gold Star

- DANFS USS Tennessee

- DANFS USS Doran

- DANFS USS Bagley

- DANFS USS Washington Archived July 8, 2010, at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- DANFS USS Helena

- DANFS USS Freestone

- DANFS USS Hocking

- DANFS USS Burleson Listed as Burlington in error on DANFs page.

References

- Richard V. Sabatini, The Philadelphia Inquirer Staff Writer: "Charles L. Carpenter, 89, A Retired Rear Admiral", Philly.com, http://articles.philly.com/1992-02-24/news/26039149_1_carpenter-navy-cross-navy-officer, 24 Feb 1992.

- Military Times: Charles Lorain Carpenter, Military Times Hall of Valor, http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=19518, accessed 15 May 2014.

- The Boston Globe: "Charles Carpenter, Pacific theater commander; at 89", issue of February 25, 1992, http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-8731269.html Archived 2014-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 15 May 2014.

- Carpenter, Charles Lorain (1976). The Descendants of Timothy Carpenter (1715–1787) of Pittstown, Rensselaer County, New York. Carpenter Family News-Journal. ASIN B000ZU0FCI. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- USNA (1926). "Midshipman Charles L. Carpenter biography entry in the United States Naval Academy 1926 Lucky Bag". USNA Lucky Bag. US Navy. Retrieved June 6, 2014. See also: Midshipman Charles L. Carpenter biography entry in Commons.

- Lucky Bag, Yearbook of the Class of 1926, United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD, 1926, p. 359, http://www.e-yearbook.com/yearbooks/United_States_Naval_Academy_Lucky_Bag_Yearbook/1926/Page_359.html, accessed 15 May 2014.

- US Navy (1952). "US Navy Biography of Captain Charles L. Carpenter, new commander of Destroyer Squadron 18". US Navy Biography. US Navy. Retrieved June 4, 2014. From Fold3

- Lademan, J. U. Jr. (1973). USS Gold Star – Flagship of the Guam Navy. December 1973. United States Naval Institute Proceedings. Retrieved May 24, 2012. Page 68-69.

- National Security Agency – Naval Security Agency Report (1986). "The Origination and Evolution of Radio Traffic Analysis – The Period between the Wars" (PDF). NSA. National Security Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2013. Retrieved June 4, 2014. DOCID: 3362395 – Approved for Release by NSA. on 06-16-2008, FOIA Case #51505 – UNCLASSIFIED See pages 31 & 32.

- Friedman, Norman (1986). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870217151. Page 274-275.

- Cook, Cape Esperance, p. 16 and 19–20; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 295–297; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 148–149; and Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225. Since not all of the Task Force 64 warships were available, Scott's force was designated as Task Group 64.2. The U.S. destroyers were from Squadron 12, commanded by Captain Robert G. Tobin in Farenholt.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 299–301, Cook, Cape Esperance, p. 42–43, 45–47, 51–53, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 154–156.

- Cook, Cape Esperance, p. 42–50, 53–56, 71, Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 300–301, D'Albas, Death of a Navy, p. 184, Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 227–228, and Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 156–157.

- Cook, Cape Esperance, p. 59, 147–151, Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 310–312, Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 170–171.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 438.

- Kilpatrick, Naval Night Battles, p. 86–89; Hammel, Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea, p. 124–126; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 239–240.

- Kilpatrick, Naval Night Battles, p. 89–90; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 239–242; Hammel, Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea, p. 129.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 439.

- Kilpatrick, Naval Night Battles, p. 90–91; Hammel, Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea, p. 132–137; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 242–243.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 441.

- Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 242–243; Hammel, Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea, p. 137–183, and Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 449. Only eight crewmen out of a total complement of 197 (combinedfleet.com) survived the sinking of Akatsuki and were later captured by U.S. forces. One of Akatsuki's survivors, Shinya Michiharu, wrote a book called The Path From Guadalcanal which states that his ship did not fire a torpedo before sinking. Michiharu's book has not been translated into English from Japanese.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 444.

- Hammel, Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea, p. 160–171; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 247.

- combinedfleet.com

- Hammel, Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea, p. 234.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 449.

- Hara, Japanese Destroyer Captain, p. 149.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 451.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 449–450.

- Hammel, Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea, p. 274–275.

- Kurzman, Left to Die, Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 456; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 257; Kilpatrick, Naval Night Battles, p. 101–103.

- George Albert DeLong (2009). "Memoirs of George Albert DeLong (26th June 1922 – 22nd March 2002)". Jane's Oceania Home. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Domagalski, John J. (2012). Sunk in Kula Gulf: The Final Voyage of the USS Helena and the Incredible Story of Her Survivors in World War II. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 978-1597978392. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- Buships War Damage Report 1944 (1943). "U. S. S. HELENA (CL50) LOSS IN ACTION KULA GULF, SOLOMON ISLANDS 6 JULY, 1943". HELENA. WAR DAMAGE REPORT No. 43. HyperWar. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- The March 1946 history of the USS Freestone is recorded in a series of images consisting of 7 pages. The first page is here.

- CAPT John C. Rice, Jr., ed.: Naval Order of the United States: Past, Present, Future, Turner Publishing Company, 2003, https://books.google.com/books?id=DY99mM57dIoC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false, p. 49.

- W. A. Shurcliff, Historian of Joint Task Force One: Bombs at Bikini, The Official Report of Operation Crossroads, prepared under the direction of the Commander of Joint Task Force One, William H. Wise & Co., New York, N.Y., 1947, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL6521684M/Bombs_at_Bikini.

- Potter 2005, p. 321.

- McFarland 1980, p. 59.

- Potter 2005, p. 322.

- McFarland 1980, p. 61.

- McFarland 1980, p. 62.

Books

- Barlow, Jeffrey G. Revolt of the Admirals: The Fight for Naval Aviation, 1945–1950. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1994. ISBN 0-16-042094-6.

- Cook, Charles O. (1992). The Battle of Cape Esperance: Encounter at Guadalcanal (Reissue ed.). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-126-2.

- Crenshaw, Russell Sydnor (1998). South Pacific Destroyer: The Battle for the Solomons from Savo Island to Vella Gulf. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-136-X.

- Domagalski, John J. (2012). Sunk in Kula Gulf: The Final Voyage of the USS Helena and the Incredible Story of Her Survivors in World War II. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 978-1597978392.

- Frank, Richard B. (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 0-14-016561-4.

- Hammel, Eric (1988). Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea: The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, November 13–15, 1942. (CA): Pacifica Press. ISBN 0-517-56952-3.

- Hara, Tameichi (1961). Japanese Destroyer Captain. New York & Toronto: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-27894-1.

- Hara, Tameichi (1961). "Part Three, The "Tokyo Express"". Japanese Destroyer Captain. New York & Toronto: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-27894-1.- Firsthand account of the first engagement of the battle by the captain of the Japanese destroyer Amatsukaze.

- Holbrook, Heber A. (1997). The loss of the USS Juneau (CL-52) and the relief of Captain Gilbert C. Hoover, commanding officer of the USS Helena (CL-50) (Callaghan-Scott naval historical monograph). Pacific Ship and Shore-Books. ASIN B0006QS91A.

- Kilpatrick, C. W. (1987). Naval Night Battles of the Solomons. Exposition Press. ISBN 0-682-40333-4.

- Kurzman, Dan (1994). Left to Die: The Tragedy of the USS Juneau. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-74874-2.

- Lippman, David H. (2006). "Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal: Turning Point in the Pacific War". The HistoryNet.com. World War II magazine. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- McFarland, Keith (1980). "The 1949 Revolt of the Admirals" (PDF). Parameters: Journal of the US Army War College Quarterly Vol. XI, No. 2. pp. 53–63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Potter, E. B. (2005). Admiral Arliegh Burke. U.S. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-692-6.

- Whitley, M J (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-225-1.