Chaco War

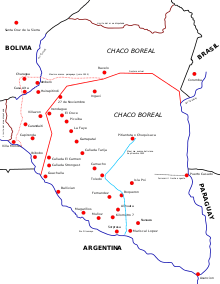

The Chaco War (1932–1935; Spanish: Guerra del Chaco, Guarani: Cháko Ñorairõ[14]) was fought between Bolivia and Paraguay over control of the northern part of the Gran Chaco region (known in Spanish as Chaco Boreal) of South America, which was thought to be rich in oil. It is also referred to as La Guerra de la Sed (Spanish for "The War of Thirst") in literary circles, for being fought in the semi-arid Chaco. It was the bloodiest military conflict fought in South America during the 20th century, between two of its poorest countries, both having previously lost territory to neighbors in 19th-century wars.

During the war, both landlocked countries faced difficulties shipping arms and supplies through neighboring countries. Bolivia faced particular external trade problems, coupled with poor internal communications. Although Bolivia had lucrative mining income and a larger, better-equipped army, a series of factors turned the tide against it, and Paraguay came to control most of the disputed zone by war's end.

The ultimate peace treaties granted two-thirds of the disputed territories to Paraguay.

Origins

The origin of the war is commonly attributed to a long-standing territorial dispute and the discovery of oil deposits on the eastern Andes range. In 1929, the Treaty of Lima ended the hopes of the Bolivian government of recovering a land corridor to the Pacific Ocean, which was thought imperative to further development and trade.[15][16] The impetus for war was exacerbated by a conflict between oil companies jockeying for exploration and drilling rights, with Royal Dutch Shell backing Paraguay and Standard Oil supporting Bolivia.[17] The discovery of oil in the Andean foothills sparked speculation that the Chaco might prove a rich source of petroleum, and foreign oil companies were involved in the exploration. Standard Oil was already producing oil from wells in the high hills of eastern Bolivia, around Villa Montes.[18] However, it is uncertain if the war would have been caused solely by the interests of these companies, and not by aims of Argentina to import oil from the Chaco.[19] In opposition to the "dependency theory" of the war's origins, the British historian Matthew Hughes argued against the thesis that Bolivian and Paraguayan governments were the "puppets" of Standard Oil and Royal Dutch Shell respectively, writing: "In fact, there is little hard evidence available in the company and government archives to support the theory that oil companies had anything to do with causing the war or helping one side or the other during the war".[20]

Both Bolivia and Paraguay were landlocked. Though the 600,000 km2 Chaco was sparsely populated, control of the Paraguay River running through it provided access to the Atlantic Ocean.[21] This became especially important to Bolivia, which had lost its Pacific coast to Chile in the 1879 War of the Pacific.[22] Paraguay had lost almost half of its territory to Brazil and Argentina in the Paraguayan War of 1864–1870. The country was not prepared to surrender its economic viability.[23]

In international arbitration, Bolivia argued that the region had been part of the original Spanish colonial province of Moxos and Chiquitos to which Bolivia was heir. Meanwhile, Paraguay based its case on the occupation of the land. Indeed, both Paraguayan and Argentine planters were already breeding cattle and exploiting quebracho woods in the area,[24] while the small nomadic indigenous population of Guaraní-speaking tribes was related to Paraguay's own Guaraní heritage. As of 1919, Argentine banks owned 400,000 hectares of land in the eastern Chaco while the Casado family, a powerful part of the Argentine oligarchy, held 141,000.[25] The presence of Mennonite colonies in the Chaco, who settled there in the 1920s under the auspices of the Paraguayan parliament, was another factor in favour of Paraguay's claim.[26]

Prelude to the war

The first confrontation between the two countries dates back to 1885, when the Bolivian entrepreneur Miguel Araña Suárez founded Puerto Pacheco, a port on the upper Paraguay river, south of Bahía Negra. He assumed that the new settlement was well inside Bolivian territory, but Bolivia had implicitly recognized Bahía Negra as Paraguayan. The Paraguayan government sent in a naval detachment aboard the gunboat Pirapó, which forcibly evicted the Bolivians from the area in 1888.[27][28] Two agreements followed—in 1894 and 1907—which neither the Bolivian nor the Paraguayan parliament ever approved.[29] Meanwhile, in 1905 Bolivia founded two new outposts in the Chaco, Ballivián and Guachalla, this time along the Pilcomayo River. The Bolivian government ignored the half-hearted Paraguayan official protest.[28]

Bolivian penetration in the region went unopposed until 1927, when the first blood was shed over the Chaco Boreal. On 27 February a Paraguayan army foot patrol and its native guides were taken prisoners near the Pilcomayo River and held in the Bolivian outpost of Fortin Sorpresa, where the commander of the Paraguayan platoon, Lieutenant Adolfo Rojas Silva, was shot and killed in suspicious circumstances. Fortín (Spanish for "little fort") was the name used for the small pillbox and trench-like garrisons in the Chaco, although the troops' barracks usually were no more than a few mud huts. While the Bolivian government formally regretted the death of Rojas Silva, the Paraguayan public opinion called it "murder".[25] After the subsequent talks arranged in Buenos Aires failed to produce any agreement and eventually collapsed in January 1928, the dispute grew violent. On 5 December 1928 a Paraguayan cavalry unit overran Fortin Vanguardia, an advance outpost established by the Bolivian army a few miles northwest of Bahía Negra. The Paraguayans captured 21 Bolivian soldiers and burnt the scattered huts to the ground.[30]

The Bolivians retaliated with an air strike on Bahía Negra on 15 December, which caused few casualties and not much damage. On 14 December Bolivia seized Fortin Boquerón, which later would be the site of the first major battle of the campaign, at the cost of 15 Paraguayan dead. A return to the status quo ante was eventually agreed on 12 September 1929 in Washington, under pressure from the Pan American League, but an arms race had already begun and both countries were on a collision course.[31] The regular border clashes might have led to war in the 1920s if either side was capable of waging war against one another.[32] As it was, neither Paraguay or Bolivia had an arms industry and both sides had to import vast quantities of arms from Europe and the United States to arm themselves for the coming conflict.[32] It was the need for both sides to import sufficient arms that held back the outbreak of the war to 1932, at which point both sides felt capable of resorting to arms to settle the long-running dispute.[32]

Composition of the armies

Bolivian infantry forces were armed with the latest in foreign weapons, including DWM Maxim M1904 and M1911 machine guns, Czech ZB vz. 26 and Vickers-Berthier light machine guns, Mauser-type Czech VZ-24 7.65mm rifles (mosquetones) and Schmeisser MP-28 II 9mm submachine guns.[33] At the outset, Paraguayan troops used a motley collection of small arms, including German Maxim, British Vickers, and Browning MG38 water-cooled machine guns, and the Danish Madsen light machine gun.[33] The primary service rifle was the M1927 7.65mm Paraguayan Long Rifle, a Mauser design based on the M1909 Argentine Long Rifle and manufactured by the Oviedo arsenal in Spain.[33][34] The M1927 rifle, which tended to overheat in rapid fire, proved highly unpopular with the Paraguyan soldiers.[33][34] Some M1927 rifles experienced catastrophic receiver failures, a fault later traced to faulty ammunition.[33][34] After the commencement of hostilities, Paraguay was able to capture sufficient numbers of Bolivian VZ-24 rifles and MP 28 submachine guns (nicknamed piripipi)[35] to equip all her front-line infantry forces.[33]

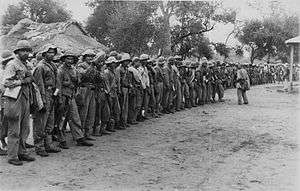

Paraguay had a population only a third as large as that of Bolivia (880,000 vs. 2,150,000), but its innovative style of fighting, centered on rapid marches and flanking encirclements, compared to Bolivia's more conventional strategy, enabled it to take the upper hand. In June 1932 the Paraguayan army totaled about 4,026 men (355 combat officers, 146 surgeons and non-combatant officers, 200 cadets, 690 NCOs and 2,653 soldiers). Both racially and culturally, the Paraguayan army was practically homogeneous. Almost all of its soldiers were European-Guaraní mestizos. Bolivia's army, however, consisted mostly of the Altiplano's aboriginals of Quechua or Aymará descent (90% of the infantry troops), the lower-ranking officers were of Spanish or other European ancestry, and the army commander-in-chief Hans Kundt was German. In spite of the fact that the Bolivian army had more manpower, it never mobilized more than 60,000 men, and never more than two-thirds of the army were on the Chaco at any one time. Paraguay, on the other hand, mobilized its entire army.[36] A British diplomat reported in 1932 that the average Bolivian had never been anywhere close to the Chaco and "had not the slightest expectation of visiting it in the course of his life".[37] Most Bolivians had little interest in fighting, let alone dying for the Chaco. Furthermore, the typical Bolivian soldier was a Quechua or Aymara peasant conscript accustomed to life high up in the Andes mountains who did not fare well in the low-lying, hot and humid land of the Chaco.[37]

Many of Paraguay's army commanders had gained combat experience as volunteers with the French army in World War 1.[38] Paraguay's army commander, Colonel (later General) later Marshal José Félix Estigarribia, soon rose to the top of Paraguayan combat command.[38] Estigarribia capitalized on the native Guarani knowledge of the forest and ability to live off the land to gain valuable intelligence on conducting his military campaigns.[38] Estigarribia preferred to bypass Bolivian garrisons and his subordinates, such as Colonel Rafael Franco, proved adept at infiltrating enemy lines, often encirling Bolivian strongholds (Paraguay held over 21,000 POWs by the war's end, against some 2,500 prisoners held by Bolivia).[38] Both sides resorted to entrenched strongpoints using barbed wire, mortars, machineguns, and mines with interlocking fields of fire.[38]

Paraguay's war effort was a total one. Buses were commandeered to transport troops, wedding rings were donated to buy weapons, and by 1935 Paraguay had widened conscription to include 17-year-olds and policemen. Perhaps the most important advantage enjoyed by Paraguay was that the Paraguayans had a rail network running to the Chaco comprising five narrow-gauge railroads totaling some 266 miles running from the river ports on the Paraguay river to the Chaco, which allowed the Paraguayan army to bring men and supplies to the front far more effectively than the Bolivians ever managed.[39] In 1928 the British Legation in La Paz reported to London that it took the Bolivian Army two weeks to march their men and supplies to the Chaco, and that Bolivia's "inordinately long lines of communication" would favor Paraguay if war should break out.[37] Furthermore, the drop in altitude from 12,000 feet in the Andes to 500 feet in the Chaco imposed further strain on Bolivia's efforts to supply its soldiers in the Chaco.[37] Bolivia's railroads did not run to the Chaco, and all Bolivian supplies and soldiers had to travel to the front on badly maintained dirt roads.[37] Hughes wrote that the Bolivian elite was well aware of these logistical problems, but throughout the war, Bolivia's leaders had a "fatalistic" outlook.[37] Bolivia's elite took it for granted that the fact that the Bolivian Army had been trained by a German military mission while the Paraguayan Army had been trained by a French military mission, together with the tough nature of their Quechua and Aymara Indian conscripts and the will to win would give them the edge in the war.[37] A recurring theme in the thinking of Bolivia's elite was that the training provided by the German military mission, the presence of several German officers like Kundt commanding their troops, and sheer willpower and determination were all that was needed for victory.[37]

Cavalry forces

While both armies deployed a significant number of cavalry regiments, these actually served as infantry, since it was soon learned that the Chaco could not provide enough water and forage for horses. Only a relatively few mounted squadrons carried out reconnaissance missions at divisional level.[40]

Armor, artillery, and motorized forces

At the insistence of the Minister of War General Hans Kundt, Bolivia purchased a number light tanks and tankettes for support of infantry forces. German instructors provided training to the mostly-Bolivian crews, who received eight weeks' training. The Vickers light tanks bought by Bolivia were the Vickers Type A and Type B, commissioned into the Bolivian army in December 1932, and were originally painted in camouflage patterns.

Hampered by the geography and difficult terrain of the Gran Chaco, combined with scarce water sources and inadequate logistical preparations, the Bolivian superiority in vehicles (water-cooled), tanks, and towed artillery in the end did not prove decisive. Thousands of truck and vehicle engines succumbed to the thick Chaco dust, which also jammed the heavy water-cooled machine guns employed by both sides.[33] Having relatively few artillery pieces of its own, Paraguay purchased a quantity of Stokes-Brandt Model 1931 mortars. Highly portable and accurate, with a range of 3,000 yards, the auguas ("corn-mashers" in Guarani) caused great losses among Bolivian troops.[33] In the course of the conflict, Paraguayan factories developed their own type of hand grenade, the carumbe'i (Guaraní for "little turtle")[41][42] and produced trailers, mortar tubes, artillery grenades and aerial bombs. The Paraguayan war effort was centralized and led by the state-owned national dockyards, managed by José Bozzano.[43][44] The Paraguayan army received the first consignment of carumbe'i grenades in January 1933.[41]

Logistics, communications, and intelligence

The Paraguayans took advantage of their ability to communicate over the radio in Guaraní, a language not spoken by the average Bolivian soldier. Paraguay had little trouble in transporting its army in large barges and gunboats on the Paraguay River to Puerto Casado, and from there directly to the front lines by railway, while the majority of Bolivian troops had to come from the western highlands, some 800 km away and with little or no logistic support. In fact, it took a Bolivian soldier about 14 days to traverse the distance, while a Paraguayan soldier only took about four.[36] The heavy equipment used by Bolivia's army made things even worse. The poor water supply and the dry climate of the region played a key role during the conflict. There were thousands of non-combat casualties due to dehydration, mostly among Bolivian troops.

Air and naval assets

The Chaco War is also important historically as the first instance of large-scale aerial warfare to take place in the Americas. Both sides used obsolete single-engined biplane fighter-bombers; the Paraguayans deployed 14 Potez 25s, while the Bolivians made extensive use of at least 20 CW-14 Ospreys. Despite an international arms embargo imposed by the League of Nations, Bolivia in particular went to great lengths in trying to import a small number of Curtiss T-32 Condor II twin-engined bombers disguised as civil transport planes, but they were stopped in Peru before they could be delivered.[45]

The valuable aerial reconnaissance produced by Bolivia's superior air force in spotting approaching Paraguayan encirclements of Bolivian forces was largely ignored by Kundt and other Bolivian army generals, who tended to dismiss such reports as exaggerations by overzealous airmen.[38][46][47]

The Paraguayan navy played a key role in the conflict by carrying thousands of troops and tons of supplies to the front lines via the Paraguay River, as well as by providing anti-aircraft support to transport ships and port facilities.[48]

Two Italian-built gunboats, the Humaitá and Paraguay ferried troops to Puerto Casado. On 22 December 1932 three Bolivian Vickers Vespas attacked the Paraguayan riverine outpost of Bahía Negra, on the Paraguay River, killing an army colonel, but one of the aircraft was shot down by the gunboat Tacuary. The two surviving Vespas met another gunboat, the Humaitá, while flying downriver. Paraguayan sources claim that one of them was damaged.[49][50] Conversely, the Bolivian army reported that the Humaitá limped back to Asunción seriously damaged.[51] Although the Paraguayan navy admitted that Humaitá was struck by machine gun fire from the aircraft, they claimed that her armour shield averted damage.[52]

Shortly before 29 March 1933 a Bolivian Osprey was shot down over the Paraguay River,[53] while on 27 April a strike force of six Ospreys launched a successful mission from their base at Muñoz against the logistic riverine base and town of Puerto Casado, although the strong diplomatic reaction of Argentina prevented any further strategic attacks on targets along the Paraguay River.[54] On 26 November 1934 the Brazilian steamer Paraguay was strafed and bombed by mistake by Bolivian aircraft, while sailing the Paraguay River near Puerto Mihanovich. The Brazilian government sent 11 naval planes to the area, and its navy began to convoy shipping on the river.[55][56][57]

The Paraguayan navy air service was also very active in the conflict, harassing Bolivian troops deployed along the northern front with flying boats. The aircraft were moored at Bahía Negra Naval Air Base, and consisted of two Macchi M.18s.[58] These seaplanes carried out the first night air attack in South America when they raided the Bolivian outposts of Vitriones and San Juan,[59] on 22 December 1934. Every year since then, the Paraguayan navy celebrates the "Day of the Naval Air Service" on the anniversary of the action.[60]

The Bolivian army deployed at least ten locally-built patrol boats and transport vessels during the conflict, mostly to ship military supplies to the northern Chaco through the Mamoré-Madeira system.[62] The transport ships Presidente Saavedra and Presidente Siles steamed on the Paraguay River from 1927 until the beginning of the war, when both units were sold to private companies. The 50-ton armed launch Tahuamanu, based in the Mamoré-Madeira fluvial system, was briefly transferred to Laguna Cáceres to ferry troops downriver from Puerto Suárez, challenging for eight months the Paraguayan naval presence in Bahía Negra. She was withdrawn to the Itenez River in northern Bolivia after Bolivian aerial reconnaissance revealed the actual strength of the Paraguayan navy in the area.[63]

Conflict

Pitiantuta Lake incident

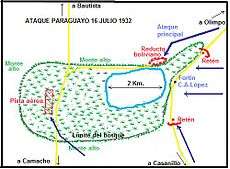

On June 15, 1932, a Bolivian detachment captured and burned to the ground the Fortín Carlos Antonio López at Pitiantutá Lake, disobeying explicit orders by Bolivian President Daniel Salamanca to avoid provocations in the Chaco region. One month later, on July 16, a Paraguayan detachment drove the Bolivian troops from the area. The lake had been already discovered by Paraguayan explorers in March 1931, but the Bolivian High Command was unaware of this when one of its aircraft spotted the lake in April 1932.

After the initial incident, Salamanca changed his status quo policy over the disputed area and ordered the outposts of Corrales, Toledo and Boquerón to be captured. The three were soon taken, and in response Paraguay called for a Bolivian withdrawal. Salamanca instead demanded that they be included in a "zone of dispute". On a memorandum directed to President Salamanca on August 30, Bolivian Gen. Filiberto Osorio expressed his concerns over the lack of a plan of operations, and attached a plan of operations focusing on an offensive from the north. At the same time Bolivian Gen. Quintanilla asked for permission to capture two additional Paraguayan garrisons, Nanawa and Rojas Silva. During August Bolivia slowly reinforced its 4,000-men-strong First Bolivian Army, already in the conflict's zone, with 6,000 men.

The breaking of the fragile status quo in the disputed areas of the Chaco by Bolivia convinced Paraguay that a diplomatic solution on agreeable terms was not possible. Paraguay gave its general staff orders to recapture the three forts. During August Paraguay mobilized over 10,000 troops and sent them into the Chaco region. Paraguayan Lieutenant Colonel José Félix Estigarribia prepared for a large offensive before the Bolivians would have mobilized their whole army.

First Paraguayan offensive

Fortín Boquerón was the first target of the Paraguayan offensive. The Boquerón complex, guarded by 619 Bolivian troops, resisted a 22-day siege by a 5,000-man Paraguayan force. An additional 2,500 Bolivians attempted to relieve the siege from the southwest but were beaten back by 2,200 Paraguayans who defended the accesses to the siege area. A few Bolivian units managed to enter Fortín Boquerón with supplies and the Bolivian Air Force dropped food and ammunition to the besieged soldiers. Having begun on 9 September, the siege ended when Fortín Boquerón finally fell on 29 September 1932.

After the fall of Fortín Boquerón, the Paraguayans continued their offensive and executed a pincer movement, which forced parts of the Bolivian force to surrender. While the Paraguayans had expected to lay a new siege on Fortín Arce, the most advanced Bolivian outpost in the Chaco, when they got there they found it in ruins. The 4,000 Bolivians who defended Arce had retreated to the southeast to Fortín Alihuatá and Saveedra.

Bolivian offensive

In December 1932 Bolivian war mobilization had concluded. In terms of weaponry and manpower, its army was ready to overpower the Paraguayans. Gen. Hans Kundt, a former German officer who was a veteran of fighting on the Eastern Front in World War I, was called by President Salamanca to lead the Bolivian counteroffensive. Kundt had served intermittently as military advisor to Bolivia since the beginning of the century and had established good relationships with officers of the Bolivian army and the country's political elites.

The Paraguayan Fortín Nanawa was chosen as the main target of the Bolivian offensive, to be followed by the command centre at Isla Poí. Their capture would allow Bolivia to reach the Paraguay River, putting the Paraguayan city of Concepción in danger. The capture of the fortines of Corrales, Toledo and Fernández by the Bolivian Second Corps were also part of Kundt's offensive plan.

In January 1933 the Bolivian First Corps began its attack on Fortín Nanawa. This stronghold was considered by the Paraguayans to be the backbone of their defenses. It had zig-zag trenches, miles of barbed wire and many machine-gun nests (some embedded in tree trunks). The Bolivian troops had previously stormed the nearby Paraguayan outpost of Mariscal López, isolating Nanawa from the south. On January 20, 1933, Kundt, in personal command of the Bolivian force, launched six to nine aircraft and 6,000 unhorsed cavalry, supported by 12 Vickers machine guns. However, the Bolivians failed to capture the fort and instead formed a defensive amphitheater in front of it. The Second Corps managed to capture Fortín Corrales and Fortín Platanillos but failed to take Fortín Fernández and Fortín Toledo. After a siege that lasted from February 26 to March 11, 1933, the Second Corps aborted its attack on Fortín Toledo and withdrew to a defensive line built 15 km from Fortín Corrales.

After the ill-fated attack on Nanawa and the failures at Fernández and Toledo, Kundt ordered an assault on Fortín Alihuatá. The attack on this fortín overwhelmed its few defenders. The capture of Alihuatá allowed the Bolivians to cut the supply route of the Paraguayan First Division. When the Bolivians were informed of the isolation of the First Division, they launched an attack on it. This attack led to the Battle of Campo Jordán, which concluded in the retreat of the Paraguayan First Division to Gondra.

In July 1933 Kundt, still focusing on capturing Nanawa, launched a massive frontal attack on the fortín, in what came to be known as the Second Battle of Nanawa. Kundt had prepared for the second attack in detail, using artillery, airplanes, tanks and flamethrowers to overcome Paraguayan fortifications. The Paraguayans, however, had improved existing fortifications and built new ones since the first battle of Nanawa. While the Bolivian two-pronged attack managed to capture parts of the defensive complex, these were soon retaken by Paraguayan counterattacks made by reserves. The Bolivians lost more than 2,000 men injured and killed in the second battle of Nanawa, while Paraguay lost only 559 men injured and dead. The failure to capture Nanawa and the heavy loss of life led President Salamanca to criticize the Bolivian high command, ordering them to spare more men. The defeat seriously damaged Kundt's prestige. In September he resigned his position as commander-in-chief, but his resignation was not accepted by the president. Nanawa was a major turning point in the war, because the Paraguayan army regained the strategic initiative that had belonged to the Bolivians since the beginning of 1933.[64]

Second Paraguayan offensive

In September Paraguay began a new offensive in the form of three separate encirclement movements in the Alihuatá area, which was chosen because Bolivian forces there had been weakened by the transfer of soldiers to attack Fortín Gondra. As a result of the encirclement campaign, the Bolivian regiments Loa and Ballivián, totaling 509 men, surrendered. The Junín regiment suffered the same fate, but the Chacaltaya regiment was able to escape encirclement due to intervention of two other Bolivian regiments.

The success of the Paraguayan army led Paraguayan President Eusebio Ayala to travel to the Chaco to promote José Félix Estigarribia to the rank of general. In that meeting the president approved Estigarribia's new offensive plan. On the other side, the Bolivians gave up their initial plan of reaching the Paraguayan capital of Asunción and moved on to defensive and attrition warfare.

The Paraguayan army executed a large-scale pincer movement against Fortín Alihuatá, repeating the previous success of these operations. Seven thousand Bolivian troops had to evacuate Fortín Alihuatá. On December 10, 1933, the Paraguayans finished the encirclement of the 9th and 4th divisions of the Bolivian army. After unsuccessful attempts to break through Paraguayan lines and having suffered 2,600 dead, 7,500 Bolivian soldiers surrendered. Only 900 Bolivian troops led by Major Germán Busch managed to slip away. The Paraguayans obtained 8,000 rifles, 536 machine guns, 25 mortars, two tanks and 20 artillery pieces from the captured Bolivians. By this time, Paraguayan forces had captured so many Bolivian tanks and armored vehicles that Bolivia was forced to purchase Steyr Solothurn 15mm anti-tank rifles in order to fend off their own armor.[33] The remaining Bolivian troops withdrew to their headquarters at Muñoz, which was set on fire and evacuated on 18 December. General Kundt resigned as chief of staff of the Bolivian army.

Truce

The massive defeat at Campo de Vía forced the Bolivian troops near Fortín Nanawa to withdraw northwest to form a new defensive line. Paraguayan Col. Rafael Franco proposed to launch a new attack against Ballivián and Villa Montes, but was turned down, as Paraguayan President Eusebio Ayala thought Paraguay had already won the war. A 20-day ceasefire was agreed upon between the warring parties on December 19, 1933. On January 6, 1934, when the armistice expired, Bolivia had reorganized its eroded army, having assembled a larger force than the one involved in its first offensive.

Third Paraguayan offensive

By the beginning of 1934 Paraguayan Gen. Estigarribia was planning an offensive against the Bolivian garrison at Puerto Suárez, 145 km upriver from Bahía Negra. The Pantanal marshes and the lack of canoes to navigate through them convinced the Paraguayan commander to drop the idea and turn his attention to the main front.[65] After the armistice's end the Paraguayan army continued its advance, capturing the outposts of Platanillos, Loa, Esteros and Jayucubás. After the battle of Campo de Vía in December the Bolivian army built up a defensive line at Magariños-La China. The Magariños-La China line was carefully built and considered to be one of the finest defensive lines of the Chaco War. However, a small Paraguayan attack on February 11, 1934, managed to breach the line, to the surprise of the Paraguayan command, forcing the abandonment of the whole defensive line. A Paraguayan offensive towards Cañada Tarija managed to surround and neutralize 1,000 Bolivian troops on March 27.

In May 1934 the Paraguayans detected a gap in the Bolivian defenses that would allow them to isolate the Bolivian stronghold of Ballivián and force its surrender. The Paraguayans worked at night to open a new route in the forests to make the attack possible. When Bolivian reconnaissance aircraft noticed this new path being opened in the forest, a plan was set up to let the Paraguayans enter halfway up the path and then attack them from the rear. The Bolivian operation resulted in the Battle of Cañada Strongest between May 18 and 25. The Bolivians managed to capture 67 Paraguayan officials and 1,389 soldiers. After their defeat at Cañada Strongest the Paraguayans continued their attempts to capture Ballivián. It was considered a key stronghold by the Bolivians, mostly for its symbolic position as the most southeastern Bolivian position left after the second Paraguayan offensive.

In November 1934 Paraguayan forces once again managed to surround and neutralize two Bolivian divisions at El Carmen. This disaster forced the Bolivians to abandon Ballivián and form a new defensive line at Villa Montes. On November 27, 1934, Bolivian generals confronted President Salamanca while he was visiting their headquarters in Villa Montes and forced him to resign, replacing him with the Vice President, José Luis Tejada. On November 9, 1934, the 12,000-man-strong Bolivian Cavalry Corps managed to capture Yrendagüé and put the Paraguayan army on the run. Yrendagüé was one of the few places with fresh water in that part of the Chaco and, while the Bolivian cavalry was marching towards La Faye from Yrendagüé, a Paraguayan force recaptured all the wells in Yrendague so that upon their return the exhausted and thirsty Bolivian troops found themselves without water; the already weakened force fell apart. Many were taken prisoner and a great number of those who avoided capture died of thirst and exposure after wandering aimlessly through the hot, dry forest. The Bolivian Cavalry Corps had previously been considered one of the best units of the new army formed after the armistice.

Last battles

After the collapse of the northern and northeastern fronts, Bolivian defenses focused on the south to avoid the fall of their war headquarters/supply base at Villa Montes. The Paraguayans launched an attack towards Ybybobó, isolating a portion of the Bolivian forces on the Pilcomayo River. The battle began on 28 December 1934 and lasted until the early days of January 1935. The result was that 200 Bolivian troops were killed and 1,200 surrendered, with the Paraguayans losing only a few dozen men. Some fleeing Bolivian soldiers were reported to have jumped into the fast-flowing waters of the Pilcomayo River to avoid capture.

After this defeat the Bolivian army prepared for a last stand at Villa Montes. The loss of that base would allow the Paraguayans to reach the proper Andes. Col. Bernardino Bilbao Rioja and Col. Oscar Moscoso were left in charge of the defenses, after other high-ranking officers declined. On 11 January 1935 the Paraguayans encircled and forced the retreat of two Bolivian regiments. The Paraguayans also managed in January to cut off the road between Villa Montes and Santa Cruz.

Paraguayan commander-in-chief Gen. José Félix Estigarribia decided then to launch a final assault on Villa Montes. On 7 February 1935 some 5,000 Paraguayans attacked the heavily fortified Bolivian lines near Villa Montes, with the aim of capturing the oilfields at Nancarainza, but they were beaten back by the Bolivian First Cavalry Division. The Paraguayans lost 350 men and were forced to withdraw north toward Boyuibé. Estigarribia claimed that the defeat was largely due to the mountainous terrain, conditions in which his forces were not used to fighting.[66] On 6 March, Estigarribia again focused all his efforts on the Bolivian oilfields, this time at Camiri, 130 km north of Villa Montes. The commander of the Paraguayan 3rd Corps, Gen. Franco, found a gap between the Bolivian 1st and 18th Infantry regiments and ordered his troops to attack through it, but they became stuck in a salient with no hope of further progress. The Bolivian Sixth Cavalry forced the hasty retreat of Franco's troops in order to avoid being cut off. The Paraguayans lost 84 troops taken prisoner and more than 500 dead were left behind. The Bolivians lost almost 200 men, although—unlike their exhausted enemies—they could afford a long battle of attrition.[67] On 15 April the Paraguayans punched through the Bolivian lines on the Parapetí River, taking over the city of Charagua. The Bolivian command launched a counter-offensive that forced the Paraguayans back. Although the Bolivian plan fell short of its target of encircling an entire enemy division, they managed to take 475 prisoners on 25 April. On 4 June 1935 a Bolivian regiment was defeated and forced to surrender at Ingavi, in the northern front, after a last attempt at reaching the Paraguay River.[68] On 12 June, the day the ceasefire agreement was signed, Paraguayan troops were entrenched only 15 km away from the Bolivian oil fields in Cordillera Province.

While the military conflict ended with a comprehensive Paraguayan victory,[69][70] from a wider point of view it was a disaster for both sides. Bolivia's Criollo elite forcibly pressed large numbers of the male indigenous population into the army, even though they felt little or no connection to the nation-state, while Paraguay was able to foment nationalist fervor among its predominantly mixed population. On both sides—but more so in the case of Bolivia—soldiers were ill-prepared for the dearth of water and the harsh conditions of terrain and weather they encountered. The effects of the lower-altitude climate had seriously impaired the effectiveness of the Bolivian army: most of its indigenous soldiers lived on the cold Altiplano at altitudes of over 12,000 feet (3,700 m). They found themselves at a physical disadvantage when called upon to fight in tropical conditions at almost sea level.[71] In fact, of the war's 100,000 casualties—about 57,000 of them Bolivian—more died from diseases such as malaria and other infections than from combat-related causes. At the same time, the war brought both countries to the brink of economic collapse.

Foreign involvement

Arms embargo and commerce

Since both countries were landlocked, imports of arms and other supplies from outside were limited to what the neighboring countries considered convenient or appropriate.

The Bolivian Army was dependent on food supplies that entered southeastern Bolivia from Argentina through Yacuíba.[72] The army had great difficulty importing arms purchased at Vickers, since both Argentina and Chile were reluctant to let war material pass through their ports. The only remaining options were the port of Mollendo in Peru and Puerto Suárez on the Brazilian border.[72] Eventually Bolivia achieved partial success after Vickers managed to persuade the British government to request that Argentina and Chile ease the import restrictions imposed on Bolivia. Internationally, the neighboring countries of Peru, Chile, Brazil and Argentina tried to avoid being accused of fueling the conflict and therefore limited the imports of arms to both Bolivia and Paraguay, although Argentina supported Paraguay behind the neutrality façade. Paraguay received military supplies, economic assistance and daily intelligence from Argentina throughout the war.[2][3]

The Argentine Army established a special detachment along the border with Bolivia and Paraguay at Formosa in September 1932, called Destacamento Mixto Formosa, in order to deal with deserters from both sides trying to cross into Argentine territory and to prevent any boundary crossing by the warring armies,[73] although the cross-border exchange with the Bolivian army was banned only in early 1934, after a formal protest by the Paraguayan government.[74] By the end of the war 15,000 Bolivian soldiers had deserted to Argentina.[75] Some native tribes living on the Argentine bank of the Pilcomayo, like the Wichí and Toba people, were often fired at from the other side of the frontier or strafed by Bolivian aircraft,[76] while a number of members of the Maká tribe from Paraguay, led by deserters who had looted a farm on the border and killed some of its inhabitants, were engaged by Argentine forces in 1933.[77] The Maká had been trained and armed by the Paraguayans for reconnaissance missions.[78] After the defeat of the Bolivian army at Campo Vía, at least one former Bolivian border outpost, Fortin Sorpresa Viejo, was occupied by Argentine troops in December 1933. This led to a minor incident with Paraguayan forces.[79][80]

Advisers and volunteers

.jpg)

A number of volunteers and hired personnel from different countries participated in the war on both sides. The high command staff of both countries was at times dominated by Europeans. In Bolivia, Gen. Hans Kundt, a German First World War Eastern Front veteran, was in command from the beginning of the war until December 1933, when he was relieved due to a series of military setbacks. Apart from Kundt, Bolivia had also been advised in the last years of the war from a Czechoslovak military mission made of First World War veterans.[81] The Czechoslovak military mission assisted the Bolivian military after the defeat of Campo Vía.[82] Paraguay was getting input from 80 former White Russian officers,[83] including two generals, Nikolai Ern and Ivan Belaieff; the latter was part of Gen. Pyotr Wrangel's staff during the Russian Civil War. In the later phase of the war Paraguay would receive training from a large-scale Italian mission.[5]

Bolivia had more than 107 Chileans fighting on its side. Three died from different causes in the last year of the conflict. The Chileans involved in the war enrolled privately and were mostly military and police officers. They were partly motivated by the unemployment caused by both the Great Depression and the political turbulence in Chile in the early 1930s (after the Chaco War ended some of the Chilean officers went on to fight in the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War).[84] The arrival of the first group of Chilean combatants in La Paz sparked protests from Paraguay and led the Chilean Congress on 7 September 1934 to approve a law that made it illegal to join the armies of countries at war.[84] This did not, however, stop the enrollment of Chileans in the Bolivian army, and it has been argued that Chilean President Arturo Alessandri Palma secretly approved of the practice in order to get rid of potentially troublesome elements of the military.[84]

The enrollment of Chilean military personnel in the Bolivian army caused surprise in Paraguay, since former Chilean president Gen. Carlos Ibáñez del Campo in 1928 had supported Paraguay after the Bolivian reprisals for the destruction of Fortin Vanguardia. The Paraguayan press denounced the Chilean government as not being neutral and went on to claim that the Chilean soldiers were mercenaries.[84] On 12 August 1934 the Chilean ambassador in Asunción was recalled back to Santiago in response to official Paraguayan support of the accusations against the Chilean government in the press. Early in the war, however, a few Chilean officers had joined the Paraguayan army.[84]

At least two Uruguayan military pilots, Benito Sánchez Leyton and Luis Tuya, volunteered for some of the most daring missions carried out by Paraguayan Air Force Potez 25s, like the resupply of besieged forces during the Battle of Cañada Strongest and the mass air strike on the Bolivian stronghold of Ballivián on 8 July 1934. During the relief mission on Cañada Strongest, Leyton's Potez nº 7 managed to come back home despite having been hit by almost 200 rounds.[85]

Argentina was a source of arms and ammunition for Paraguay. The Argentine military attaché in Asuncion, Col. Schweizer, continued to advise the Paraguayan command well after the start of hostilities. However, the more valuable contribution to the Paraguayan cause came from Argentine military intelligence (G2), led by Col. Esteban Vacareyza, which provided nightly reports on Bolivian movements and supply lines running along the border with Argentina.[86] Argentine First World War veteran pilot Vicente Almandoz Almonacid was appointed Director of Military Aviation by the Paraguayan government from 1932 to 1933.[87]

The open Argentine support for Paraguay was also reflected on the battlefield when a number of Argentine citizens, largely from Corrientes and Entre Ríos, volunteered for the Paraguayan army.[88] Most of them served in the 7th Cavalry Regiment "General San Martín" as infantrymen. They fought against the Bolivian Regiments "Ingavi" and "Warnes" at the outpost of Corrales on 1 January 1933, where they had a narrow escape after being outnumbered by the Bolivians. The commander of the "Warnes" Regiment, Lt. Col. Sánchez, was killed in an ambush set up by the retreating forces, while the volunteers lost seven trucks.[89] The greatest achievement of "San Martín" took place on 10 December 1933, when the First Squadron, led by 2nd Lieutenant Javier Gustavo Schreiber, ambushed and captured the two surviving Bolivian Vickers six-ton tanks on the Alihuatá-Savedra road, in the course of the battle of Campo Vía.[90]

A major supporter of Paraguay was the United States Senator and radical populist Huey Long. In a speech on the Senate floor on 30 May 1934, Long claimed the war was the work of "the forces of imperialistic finance", maintaining that Paraguay was the rightful owner of the Chaco, but that Standard Oil, whom Long called "promoter of revolutions in Central America, South America and Mexico" had "bought" the Bolivian government and started the war because Paraguay was unwilling to grant them oil concessions.[91] Because Long believed that Standard Oil was supporting Bolivia, he was very pro-Paraguayan and in a speech about the war on the Senate floor on 7 June 1934 called Standard Oil "domestic murders", "foreign murders", "international conspirators" and "rapacious thieves and robbers".[92] As a result, Long became a national hero in Paraguay and in the summer of 1934, when the Paraguayans captured a Bolivian fort, it was renamed Fort Long in his honour.[93]

Aftermath

By the time a ceasefire was negotiated for noon June 10, 1935, Paraguay controlled most of the region. In the last half-hour, there was a senseless shootout between the armies. That was recognized in a 1938 truce, signed in Buenos Aires in Argentina and approved in a referendum in Paraguay, by which Paraguay was awarded three quarters of the Chaco Boreal, 20,000 square miles (52,000 km2). Bolivia was awarded navigation rights on the Paraguay and Paraná Rivers although it had been provided with such access before the conflict.[94] Two Paraguayans and three Bolivians died for every square mile. Bolivia got the remaining territory that bordered Puerto Busch.

The war cost both nations dearly. Bolivia lost between 56,000-65,000 dead, comprising 2% of its population while Paraguay lost about 36,000 dead, comprising 3% of its population.[95]

Paraguay captured 21,000 Bolivian soldiers and 10,000 civilians (1% of the Bolivian population); many of the captured civilians chose to remain in Paraguay after the war.[96] In addition, 10,000 Bolivian troops, many of them ill-trained and ill-equipped conscripts, deserted to Argentina or injured or mutilated themselves to avoid combat.[96] By the end of hostilities, Paraguay had captured 42,000 rifles, 5,000 machine guns and submachine guns, and 25 million rounds of ammunition from Bolivian forces.[33]

Bolivia's stunning military blunders during the Chaco War led to a mass movement, known as the Generación del Chaco, away from the traditional order,[97] which was epitomised by the MNR-led Revolution of 1952.

A final document to demarcate the border based on the 1938 border settlement was signed on April 28, 2009, in Buenos Aires.[98]

Over the succeeding 77 years, no commercial amounts of oil or gas were discovered in the portion of the Chaco awarded to Paraguay, until 26 November 2012, when Paraguayan President Federico Franco announced the discovery of oil in the area of the Pirity river.[99] He claimed that "in the name of the 30,000 Paraguayans who died in the war," the Chaco would soon be "the richest oil zone in South America" and "the area with the largest amount of oil."[100] In 2014, Paraguay made its first major oil discovery in the Chaco Basin, with the discovery of light oil in the Lapacho X-1 well.[101]

Oil and gas resources extend also from the Villa Montes area and the portion of the Chaco awarded to Bolivia northward along the foothills of the Andes. Today, the fields give Bolivia the second largest resources of natural gas in South America after Venezuela.[102]

Cultural references

Augusto Céspedes, the Bolivian ambassador to UNESCO, and one of the most important Bolivian writers of the 20th century, has written several books describing different aspects of the conflict. As a war reporter for the newspaper El Universal Céspedes had witnessed the penuries of the war, which he described in Crónicas heroicas de una guerra estúpida ("Heroic Chronicles of a stupid war") among other books. Several of his fiction works, considered masterworks of the genre, have used the Chaco War conflict as a setting. Another diplomat and important figure of Bolivian literature, Adolfo Costa du Rels, has written about the conflict, his novel Laguna H3 published in 1938 is also set in the Chaco War.

One of the masterpieces of Paraguayan writer Augusto Roa Bastos, the 1960 novel Hijo de Hombre, describes in one of its chapters the carnage and harsh war conditions during the siege of Boquerón. The author himself took part in the conflict, joining the army medical service at the age of 17. The Argentine film Hijo de Hombre or Thirst, directed by Lucas Demare in 1961 is based on this part of the novel.

In Pablo Neruda's poem, Standard Oil Company, Neruda refers to the Chaco War in the context of the role that oil companies played in the war.[103]

The Chaco War, particularly the brutal battle of Nanawa, plays an important role in the adventure novel Wings of Fury, by R.N. Vick.[104]

The Paraguayan polka, "Regimiento 13 Tuyutí", composed by Ramón Vargas Colman and written in Guaraní by Emiliano R. Fernández, remembers the Paraguayan Fifth Division and its exploits in the battles around Nanawa, in which Fernández fought and was injured.[105] On the other side, the siege of Boquerón inspired "Boquerón abandonado", a Bolivian tonada recorded by Bolivian folk singer and politician Zulma Yugar in 1982.[106]

The Broken Ear, one of the Adventures of Tintin series of comic stories by Belgian author Hergé (Georges Remi) is set during a fictionalised account of the war between the invented nations of San Theodoros and Nuevo Rico.

Federico Funes, an Argentine aviator and writer, published "Chaco: Sudor y Sangre" (Chaco: Sweat and Blood), a fictionalised story about an Argentine volunteer pilot fighting for Paraguay in the 1930's.

Barrage of Fire by Bolivian novelist Oscar Cerruto, narrates the cruel realities of life in Bolivia during the war through the experiences of a young protagonist.[107]

See also

References

- de Quesada, A. M. (2011). The Chaco War 1932–1935: South America's Greatest Modern Conflict. Osprey Publishing.

- English, Adrian (2007). The Green Hell: A Concise History of the Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay, 1932–1935. Spellman.

- Farcau, Bruce (1996). The Chaco War: Bolivia and Paraguay, 1932–1935. Praeger.

- Finot, Enrique (1934). The Chaco War and the United States. L&S Print Co.

- Garner, William (1966). The Chaco Dispute; A Study in Prestige Diplomacy. Public Affairs Press.

- Zook, David (1960). The Conduct of the Chaco War. Bookman.

Notes

- Hughes, Matthew. "Logistics and the Chaco War Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932-1935". The Journal of Military History. 69(2) - April 2005.

- Abente, Diego. 1988. Constraints and Opportunities: Prospects for Democratization in Paraguay. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs.

- La ayuda argentina al Paraguay en la guerra del Chaco, Todo es Historia magazine, n° 206. julio de 1984, pág. 84 (in Spanish)

- Atkins, G. Pope (1997) Encyclopedia of the Inter-American System. Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 71. ISBN 0313286000

- The Gran Chaco War: Fighting for Mirages in the Foothills of the Andes, article from Chandelle Magazine availeable at The World at War site.

- Baďura, Bohumil (2006) Československé zbraně a diplomacie ve válce o Gran Chaco, p. 35.

- Victimario Histórico Militar DE RE MILITARI

- Marley, David, Wars of the Americas (1998)

- Dictionary of Twentieth Century World History, by Jan Palmowski (Oxford, 1997)

- Sienra Zabala, Roberto (2010). Síntesis de la Guerra del Cjhaco. Francisco Aquino Zavala, Concepción (in Spanish)

- Bruce Farcau, The Chaco War (1991)

- Singer, Joel David, The Wages of War. 1816-1965 (1972)

- Eckhardt, William, in World Military and Social Expenditures 1987-88 (12th ed., 1987) by Ruth Leger Sivard.

- Mombe’uhára Paraguái ha Boliviaygua Jotopa III, Cháko Ñorairõ rehegua. Secretaría Nacional de Cultura de Paraguay

- Hunefeldt, Christine, A Brief History of Peru, New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc., (2004) p. 149

- Morales Q., Waltraud, Brief History of Bolivia. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc., (2003)p. 83

- "Para la mayoría de las voces, el conflicto entre Bolivia y Paraguay (1932-1935) tuvo su origen en el control del supuesto petróleo que pronto iría a fluír desde el desierto chaqueño en beneficio de la nación victoriosa."Archondo, Rafael, "La Guerra del Chaco: ¿hubo algún titiritero?", POBLACIÓN Y DESARROLLO, 34: 29

- Mazzei, Umberto. "Fragmentos de vieja historia petrolera" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- Archondo, Rafael, "La Guerra del Chaco: ¿hubo algún titiritero?", POBLACIÓN Y DESARROLLO, 34: 29–39

- Hughes, Matthew "Logistics and the Chaco War: Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932-1935" pages 411-437 from The Journal of Military History, Volume 69, Issue # 2 April 2005 page 415

- Hughes, Matthew "Logistics and the Chaco War: Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932-1935" pages 411-437 from The Journal of Military History, Volume 69, Issue # 2 April 2005 page 412

- Guerra entre Bolivia y Paraguay: 1928-1935 Archived 2014-03-26 at the Wayback Machine by Ana Maria Musico Aschiero (in Spanish)

- The Chaco War

- Farcau, Bruce W. (1996). The Chaco War: Bolivia and Paraguay, 1932–1935. Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-275-95218-1

- Farcau, p. 11

- Hughes, Matthew (2005). Logistic and Chaco War: Bolivia vs. Paraguay, 1932–1935 The Journal of Military History, Volume 69, pp. 411–437

- Farcau, p. 8

- La Armada Paraguaya: La Segunda Armada (in Spanish)

- Farcau, p. 9

- Farcau, pp. 12–13

- Farcau, p. 14

- Hughes, Matthew "Logistics and the Chaco War: Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932-1935" pages 411-437 from The Journal of Military History, Volume 69, Issue # 2 April 2005 page 416.

- Severin, Kurt, Guns In the 'Green Hell' Of The Chaco, Guns Magazine, Nov. 1960, Vol. VI, No. 11-71, pp. 20-22,40-43

- Mowbray, Stuart C. and Puleo, Joe, Bolt Action Military Rifles of the World, Andrew Mowbray Publishers, Inc. 1st Ed. ISBN 9781931464390 (2009), p. 285: After the war, an enterprising arms dealer purchased the remaining M1927 rifles and re-exported them back to Spain, where they were hastily refurbished and re-issued to Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War.

- "Algunas armas utilizadas en la guerra del Chaco 1932-1935". Aquellas armas de guerra (in Spanish). 2013-09-20. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- Scheina, Robert L. (2003). "Latin America's Wars Volume II: The Age of the Professional Soldier, 1900–2001." Washington D.C.: Brasseys. ISBN 978-1-57488-452-4

- Hughes, Matthew "Logistics and the Chaco War: Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932-1935" pages 411-437 from The Journal of Military History, Volume 69, Issue # 2 April 2005 page 428.

- Fernandez, Col. Carlos José, La Guerra del Chaco Vols I-IV, La Paz: Impresora Oeste (1956)

- Hughes, Matthew "Logistics and the Chaco War: Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932-1935" pages 411-437 from The Journal of Military History, Volume 69, Issue # 2 April 2005 page 435.

- Farcau, p. 185

- González, Antonio E. (1960). Yasíh Rendíh. Editorial el Gráfico, p.61 (in Spanish)

- Bodies of Paraguayan carumbe'i grenades Archived 2014-02-27 at the Wayback Machine Museum "Villar Cáceres"

- Astillero Carmelo de MDF SA (in Spanish)

- Cardozo, Efraím (1964). Hoy en Nuestra Historia. Ed. Nizza, p. 15

- Dan Hagedorn and Antonio L. Sapienza, Aircraft of the Chaco War 1928–1935, Schiffer Publishing Ltd, Atglen PA, 1997, ISBN 978-0-7643-0146-9

- Thompson, R. W., An Echo of Trumpets, London: George Allen and Unwin (1964), pp. 27-64

- Zook, David H., The Conduct of the Chaco War, New Haven, CT: Bookman Publishing (1960)

- "Landlocked navies". Archived from the original on 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- Richard, Nicolás (2008). Mala guerra: los indígenas en la Guerra del Chaco, 1932–1935. CoLibris, pp. 286–288.ISBN 978-99953-869-3-1 (in Spanish)

- Dávalos, Rodolfo (1974). Actuación de la marina en la Guerra del Chaco: puntos de vista de un ex-combatiente. El Gráfico, page 69 (in Spanish)

- Villa de la Tapia, Amalia (1974). Alas de Bolivia: La Aviación Boliviana durante la Campaña del Chaco. N/A, p. 181 (in Spanish)

- Farina, Bernardo Neri (2011).José Bozzano y la Guerra del Material. Colección Protagonistas de la Historia, Editorial El Lector, Online edition, Chapter El Viaje Inolvidable. (in Spanish)

- Hagedorn and Sapienza, p. 21

- Hagedorn and Sapienza, p. 23

- Brazil gets apology for Bolivian attack The New York Times, 29 November 1934

- Brazilian ship is fired upon Associated Press, 27 November 1934

- Brazilian boat bombed in Chaco Glasgow Herald, 27 November 1934

- Hagedorn & Sapienza, pp. 61–64

- Scheina, page 102

- Los Ecos del primer Bombardeo Nocturno en la Guerra del Chaco, Chaco-Re, No. 28 (julio/septiembre 1989), 12–13. (in Spanish)

- Scheina, Robert L. (1987). Latin America: a naval history, 1810–1987. Naval Institute Press, p. 124. ISBN 978-0-87021-295-6

- Historial de combate de la patrullera V-01 Tahuamanu. Fuerza Naval Boliviana, Comando Naval, La Paz (in Spanish)

- Farcau, p. 132

- Farcau, p. 168

- Farcau, p. 224-225

- Farcau, p. 226

- Farcau, 229

- "Paraguayan victory in the Chaco War doubled the national territory and worked wonders for national pride." Chasteen, John Charles (2001). Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. Norton, p. 176. ISBN 978-0-393-05048-6

- "The architect of the Paraguayan victory was General Estigarribia, who fought a brilliant war of maneuver." Goldstein, Erik (1992). Wars and peace treaties, 1816–1991. Routledge, p.185. ISBN 978-0-415-07822-1

- English, Adrian J. "The Green Hell: A Concise History of the Chaco War Between Bolivia and Paraguay 1932–1935." Gloucestershire: Spellmount Limited, 2007.

- Hughes, Matthew. 2005. Logistics and the Chaco War: Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932–1935

- Gordillo, Gastón and Leguizamón, Juan Martín (2002). El río y la frontera: movilizaciones aborígenes, obras públicas y MERCOSUR en el Pilcomayo. Biblos, p. 44. ISBN 978-950-786-330-1 (in Spanish)

- Gordillo & Leguizamón, p. 45

- Casabianca, Ange-François (1999). Una Guerra Desconocida: La Campaña del Chaco Boreal (1932–1935) Editorial El Lector. ISBN 978-99925-51-91-2 (in Spanish)

- Gordillo & Leguizamón, p. 43

- Figallo, Beatriz (2001). Militares e indígenas en el espacio fronterizo chaqueño. Un escenario de confrontación argentino-paraguayo durante el siglo XX. Page 11. (in Spanish)

- Capdevila, Luc, Combes, Isabel, Richard, Nicolás and Barbosa, Pablo (2011). Los hombres transparentes. Indígenas y militares en la guerra del Chaco. p. 97. ISBN 978-99954-796-0-2 (in Spanish)

- Campbell Barker, Eugene and Eugene Bolton, Herbert (1951). Southwestern historical quarterly, Volumen 54. Texas State Historical Association in cooperation with the Center for Studies in Texas History, University of Texas at Austin, p. 250

- Estigarribia, José Félix (1969).The epic of the Chaco: Marshal Estigarribia's memoirs of the Chaco War, 1932–1935. Greenwood Press, pp. 115 and 118

- Farcau, p. 184

- "The Gran Chaco War, 1928-1935". worldatwar.net. Retrieved 2016-04-06.

- Белая гвардия джунглей. Как немцы проиграли войну русским.. в Южной Америке [The White Guard of the Jungle. How Germans Lost War to Russians... in South America] (in Russian). Argumenty i Fakty. 27 January 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Jeffs Castro, Leonardo (2004), "Combatientes e instructores militares chilenos en la Guerra del Chaco Difficulties", Revista Universum, 19 (1): 58–85, doi:10.4067/s0718-23762004000100004

- Hagedorn & Sapienza, pp. 34–35

- Farcau, p. 95

- Vicente Almandoz Almonacid Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish)

- Ayala Moreira, Rogelio (1959). Por qué no ganamos la Guerra del Chaco. Tall. Gráf. Bolivianos, p. 239 (in Spanish)

- Farcau, p. 91

- Sigal Fogliani, Ricardo (1997). Blindados Argentinos, de Uruguay y Paraguay. Ayer y Hoy, p. 149. ISBN 978-987-95832-7-2 (in Spanish)

- Gillette, Michael "Huey Long and the Chaco War" pages 293-311 from Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Volume 11, Issue # 4, Autumn 1970 page 297.

- Gillette, Michael "Huey Long and the Chaco War" pages 293-311 from Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Volume 11, Issue # 4, Autumn 1970 pages 300-301.

- Gillette, Michael "Huey Long and the Chaco War" pages 293-311 from Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Volume 11, Issue # 4, Autumn 1970 page 300.

- Glassner, M.I., The Transit Problems Of Landlocked States: the Cases of Bolivia and Paraguay, Ocean Yearbook 4, E.M. Borghese and M. Ginsburg (eds)., Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, pp. 366-389

- Hughes, Matthew "Logistics and the Chaco War: Bolivia versus Paraguay, 1932-1935" pages 411-437 from The Journal of Military History, Volume 69, Issue # 2 April 2005 page 412.

- de Quesada, Alejandro, The Chaco War 1932–35: South America’s Greatest Modern Conflict, Oxford UK: Osprey Publishing Ltd, ISBN 9781849084161 (2011), p. 22

- Gómez, José Luis (1988). Bolivia, un pueblo en busca de su identidad Editorial Los Amigos del Libro, p. 117. ISBN 978-84-8370-141-6 (in Spanish)

- Bolivia, Paraguay Settle Border Conflict from Chaco War

- "Paraguay encontró petróleo cerca de la frontera con la Argentina" La Nación, 26 November 2012 (in Spanish)

- "Paraguay asegura que tendrá la región petrolera más rica de Sudamérica" La Nación, 4 December 2012 (in Spanish)

- President Energy Finds Oil In Paraguay’s Chaco Basin, Bloomberg News, 20 October 2014, retrieved 30 July 2018

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-01. Retrieved 2012-09-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Standard Oil Co. by Pablo Neruda

- Vick, R. N. (June 12, 2014). Wings of Fury. Black Rose Writing. ISBN 9781612963693.

- "13 Tuyutí" clip with Chaco war footage

- "Boquerón abandonado" clip with some war footage and reenacments

- "Aluvión de fuego - EcuRed". www.ecured.cu (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-09-05.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chaco War. |

- The White Russian contribution in the Chaco War

- Tamaño, Gustavo Adolfo (2008). Historias Olvidadas: Tanques en la Guerra del Chaco—The surviving Bolivian Vickers A tank on display at La Paz Military College (in Spanish)

- Photographs of the Paraguayan gunboats Humaitá and Paraguay as of 2005 (in Spanish)

- Bolivian armed launch Tahuamanu on display—Riberalta, Beni Department, Bolivia (in Spanish)