Battle of Campo Grande

The Battle of Campo Grande was a major engagement which took place during the Chaco War, in the southern region of the Chaco Boreal. During this battle, the Paraguayan Army successfully encircled two Bolivian regiments defending two of the three flanks of Fort Alihuatá, forcing them to surrender.

| Battle of Campo Grande | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Chaco War | |||||||

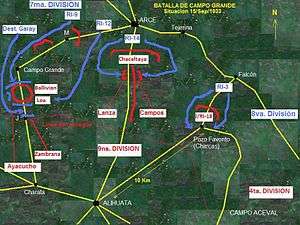

Map of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hans Kundt Carlos Banzer Rafael González Quint José Capriles |

J.F. Estigarribia José Ortiz Eugenio Garay | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Reg. "Loa", "Ballivián", "Chacaltaya" Apoyo: Regimientos 18, "Lanza", "Campos", "Ayacucho" | 9th Division | ||||||

Location within Paraguay | |||||||

The encirclement

The battle of Gondra had forced the Bolivian high command to remove troops from the front of the 9th Division that defended Alihuatá, leaving the advanced area of the stronghold with only three scattered units. Seven hundred men of the Chacaltaya regiment remained entrenched near Arce, riding the road coming from Alihuatá, while the Ballivián regiment was deployed five kilometres to the left, in Campo Grande. The Bolivian command deployed a company of the Junín regiment in Pozo Favorito, four kilometers from the Chacaltaya, on the right side of the screen.

The Paraguayan command was aware of the weakness of the Bolivian deployment. Reconnaissance patrols learned of the shortage of personnel and the isolation of the three outposts. They surrounded the Bolivian troops through three simultaneous operations. On 30 August Paraguayan artillery pounded the trenches of the Chacaltaya regiment, while infantry forces assaulted the flanks. A small Bolivian detachment left Alihuatá to bring relief to the Chacaltaya but failed to clear the way.

Another strong Bolivian detachment, consisting of the 18th Regiment, managed to evict the Paraguayans, cleaning up the rearguard of the Chacaltaya. The Paraguayan command, however, was ready to repeat this diversional maneuver. General Kundt, who was in the Bullo sector controlling the operation from the barracks at Muñoz, had left specific instructions that the Loa regiment should not be used without his permission. Lieutenant Colonel Toro, who was nominally Chief of Operations of the high command but had no authority other than relaying news received from various fronts to Kundt at Muñoz, received a distress message from the 9th Division that said the Chacaltaya was being surrounded again and that the Ballivián regiment also was in danger. As Toro was trying to contact Kundt to obtain authorization to deploy the Loa regiment, the situation of the Ballivián and the Chacaltaya was deteriorating.

Breakout attempt

Lieutenant Colonel Toro decided on his own to move the Loa regiment from Gondra to Campo Grande to support the Ballivián regiment. Upon learning of this General Kundt scolded Toro and traveled to Alihuatá to see the situation himself. He and Colonel Banzer, Commander of the 9th Division, assumed that the center of gravity of the Paraguayan offensive was the attack against the Chacaltaya regiment, in the path of Alihuatá-Arce. The truth was that the Paraguayans there had very little strength. On the other hand, in Campo Grande the Paraguyan army deployed an entire division, the 7th.[1]

The Loa regiment tried to shore up the Ballivián line to prevent the enemy from flanking it, but the Paraguayan troops deployed their forces in such a manner as to threaten to surround both units. A baffled Colonel Banzer went to Campo Grande and issued emergency measures on his return to Alihuatá, but he was observed by Paraguayan patrols which had also closed that pathway. A Paraguayan account states:

We saw a passing truck carrying a blond high official of uncertain age, we assumed that he was a senior officer, but we abstained from ambush them to keep the surprise.

On September 12, 1933, the route Charata-Campo Grande was occupied by the Paraguayans, who consequently cornered the Bolivian regiments Ballivián and Loa. The Paraguayan pressure became more intense on both the north and east. The Paraguayans, intending to quickly decide the battle, broke through the Ballivián's line, and the Bolivians were forced to send such troops as kitchen help and couriers to close the gap. During the night the Paraguayan pressure remained constant. Colonel Rafael Gonzalez Quint, head of the Ballivián regiment, suggested asking for reinforcements but Colonel José Capriles, Commander of the Loa who had assumed leadership of the detachment consisting of these two regiments, was opposed. The reason was that Colonel Banzer, on the last visit to his command, had notified him that the 9th Division no longer had any reserves and that all available men were going to be used to help the Chacaltaya regiment that was to be defending the road to Arce, which the enemy would se for its main route of attack. Colonel Capriles did not encourage them to try an offensive on their own, since he knew that a retreat was the most reasonable course of action before the Paraguayans' encirclement of their forces made it impossible. On the evening of the second day of siege, loud noises of fighting were heard coming from the side of Alihuatá: it was the Zambrana company of the Loa regiment, which was in another sector and had come to the relief of the besieged. After half an hour the noise died down; Captain Julio Zambrana Bayá and many of his colleagues had died in the rescue bid. The Ayacucho regiment was taken out of Nanawa for another relief attempt. Colonel Ortiz, head of the Paraguayan 7th Division, had established three lines in this sector, looking towards Alihuatá—one to stop Bolivian reinforcements leaving the fort, another to harass the besieged and the third, in the middle, to come and go in support of one or the other wall.[2]

Desperate situation

Some aircraft were able to throw bags of coca into the fencing. On September 15, the third day of the siege, a hellishly sun increased the thirst of the Bolivian troops. Four trucks had brought water shortly before the encirclement was completed. The supply was carefully share out to half a litre per day per person. Thirst prevented the soldiers to eat the pieces of meat that was feed them. Their dry throats simply did not allow them to swallow the food. According to 2nd Lieutenant Benigno Guzmán:

Day 15. 17 Hours: they bring some water, the supply to the troops caused us several casualties, because all are desperate. They do not want the coca that dropped our aircraft, or the cigarretes… some soldiers don't recognize me, others just cry. 10 Hours: I talk with mayor Cárdenas. The exhausted soldiers only can shout out "water! water! water!" ... and the Paraguayans are offering us water, threatening in addition to cut our throats … at noon, the Paraguayans stormed the pen's sector… they carried out another assault, on the entire front this time … Three men get out from the trench, one of them wounded. Another survivor is a Sergeant, who tells me: "the Paraguayans have entered and caught them all"... the few of us still standing attempted to run away towards the headquarters… I was dragged out of the bushes, and they asked me to surrender…everything was lost by then.|Diary 2nd Lieutenant Benigno Guzmán (Querejazu Calvo, 1981, pág. 227)

Surrender

On the western side a Paraguayan official formally raised the surrender of Bolivian units, giving an hour of term for the response. The Paraguayan pressure was felt everywhere and many soldiers were delivering. After consulting his officers, Colonel Capriles agreed to meet with a parliamentary enemy. The veteran Lieutenant Colonel Eugenio Garay joined the Bolivian command post on behalf of the Commander of the Paraguayan Division, Lieutenant Colonel José A. Ortiz, to enter into the terms of the surrender.

And while the Bolivian aircraft threw cans and Paraguayan soldiers offered some water to the Bolivian troops, the Act of surrender was signed. A total of 509 troops capitulated, among them two colonels, 11 officers, three surgeons and ten non-commissioned officers.

Five hours earlier, ten kilometres to the right, the shrinking company of the "Junín" regiment, defending Pozo Favorito had also been forced to capitulate.

In the Centre, the "Chacaltaya" regiment broke through a second overrun attempt with the help of two units, the "Campos" regiment, launched the assault three times in a row, and the "Lanza" cavalry regiment, who managed to open a safe path on a flank.

Assessment

This battle, despite the small units engaged in it, is important because it marks a change of strategy for the Paraguayan army. Commander Estigarribia was unable to assess the State that was the operational capacity of the enemy army. It was easy to observe the reactions slow and hesitant of the Bolivian command, returning to the tactic of sending reinforcements in small quantities and where the situation was almost hopeless. It was also observed, in the prisoners captured, tiredness and the growing demoralization that widespread in officers and soldiers Bolivians who distrusted more and more orders received from their senior commanders. The Paraguayan Commander Ortiz, which directly addressed the entire operation, could maintain in secret the main direction of his attack until the last minute, denying the enemy time for regrouping their forces.

Notes

- Querejazu Calvo, 1981, pags.225-226

- Querejazu Calvo, 1981, pág. 227

Bibliography

- Querejazu Calvo, Roberto: Masamaclay. Historia política, diplomática y militar de la guerra del Chaco. Cochabamba-La Paz (Bolivia): Los Amigos del Libro, 4.ª edición ampliada, 1981 (in Spanish)