Cerebral folate deficiency

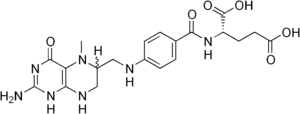

Cerebral folate deficiency is a condition in which concentrations of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are low in the brain as measured in the cerebral spinal fluid despite being normal in the blood.[3] Symptoms typically appear at about 5 to 24 months of age.[3][2] Without treatment there may be poor muscle tone, trouble with coordination, trouble talking, and seizures.[3]

| Cerebral folate deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cerebral folate deficiency syndrome, neurodegeneration due to cerebral folate transport deficiency, cerebral folate transport deficiency, FOLR1 deficiency[1][2] |

| |

| 5-methyltetrahydrofolate is decreased in concentration in the human brain | |

| Causes | Genetic disorder[2], autoantibodies |

| Diagnostic method | Lumbar puncture |

| Medication | Folinic acid |

| Frequency | FOLR1 mutation, <20 described cases[2] |

One cause of cerebral folate deficiency is a mutation in a gene responsible for folate transport, specifically FOLR1.[2][4] This is inherited from a person's parents in an autosomal recessive manner.[2] Other causes appear to be Kearns–Sayre syndrome[5] and autoantibodies to the folate receptor.[6][7][8]

For people with the FOLR1 mutation, even when the systemic deficiency is corrected by folate, the cerebral deficiency remains and must be treated with folinic acid. Success depends on early initiation of treatment and treatment for a long period of time.[9][3] Fewer than 20 people with the FOLR1 defect have been described in the medical literature.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Children with the FOLR1 mutation are born healthy. Symptoms typically appear at about 5 to 24 months of age. The symptoms get worse with time. Without treatment there may be poor muscle tone, trouble with coordination, trouble talking, and seizures.[2][3]

Causes

One cause of cerebral folate deficiency is due to a genetic mutation in the FOLR1 gene. It is inherited from a person's parents in an autosomal recessive manner.[2] Other causes appear to be Kearns–Sayre syndrome[5] and autoantibodies to the folate receptor.[6][7][8]

Furthermore, secondary cerebral folate deficiency can develop in patients suffering from other conditions. For example, it can develop in AADC deficiency through the depletion of methyl donors, such as SAM and 5-MTHF, by O-methylation of the excessive amounts of L-dopa present in patients.[10][11]

Treatment

For people with the FOLR1 mutation, even when the systemic deficiency is corrected by folate, the cerebral deficiency remains, and must be treated with folinic acid. Success depends on early initiation of treatment.[9] Treatment requires taking folinic acid for a significant period of time.[3] Fewer than 20 people with the FOLR1 defect have been described in the medical literature.[2] Treatment with pharmacologic doses of folinic acid has also led to reversal of some symptoms in children diagnosed with cerebral folate deficiency and testing positive for autoantibodies to folate receptor alpha.[12]

External links

- Cerebral Folate Deficiency - description (2019) on the website of the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD).

References

- "Cerebral folate deficiency". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Cerebral folate transport deficiency". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Gordon, N (2009). "Cerebral folate deficiency". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 51 (3): 180–182. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03185.x. PMID 19260931.

- Serrano M, Pérez-Dueñas B, Montoya J, Ormazabal A, Artuch R (2012). "Genetic causes of cerebral folate deficiency: clinical, biochemical and therapeutic aspects". Drug Discovery Today. 17 (23–24): 1299–1306. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2012.07.008. PMID 22835503.

- Baumgartner, MR (2013). Vitamin-responsive disorders: cobalamin, folate, biotin, vitamins B1 and E. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 113. pp. 1799–1810. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-59565-2.00049-6. ISBN 9780444595652. PMID 23622402.

- Hyland K, Shoffner J, Heales SJ (2010). "Cerebral folate deficiency". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 33 (5): 563–570. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9159-6. PMID 20668945.

- Agadi S, Quach MM, Haneef Z (2013). "Vitamin-responsive epileptic encephalopathies in children". Epilepsy Research and Treatment. 2013: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2013/510529. PMC 3745849. PMID 23984056.

- Phillip L. Pearl, MD (4 October 2012). Inherited Metabolic Epilepsies. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-61705-056-5.

- Zhao R, Aluri S, Goldman ID (2017). "The proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT-SLC46A1) and the syndrome of systemic and cerebral folate deficiency of infancy: Hereditary folate malabsorption". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 53: 57–72. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2016.09.002. PMC 5253092. PMID 27664775.

- Wassenberg, et al. (2017). "Consensus guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency". Orphanet J Rare Dis.

- Pope S, Artuch R, Heales S, Rahman S (July 2019). "Cerebral folate deficiency: Analytical tests and differential diagnosis". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 42 (4): 655–672. doi:10.1002/jimd.12092. PMID 30916789.

- Desai A, Sequeira JM, Quadros EV (2016). "The metabolic basis for developmental disorders due to defective folate transport". Biochimie. 126: 31–42. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2016.02.012. PMID 26924398.