Thomas Cavalier-Smith

Thomas (Tom) Cavalier-Smith, FRS, FRSC, NERC Professorial Fellow (born 21 October 1942), is a Professor of Evolutionary Biology in the Department of Zoology, at the University of Oxford.[1] His research has led to discovery of a number of unicellular organisms (protists) and definition of taxonomic positions, such as introduction of the kingdom Chromista, and other groups including Chromalveolata, Opisthokonta, Rhizaria, and Excavata. He is well known for his system of classification of all organisms.

Thomas Cavalier-Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 October 1942 London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge King's College London |

| Known for | Cavalier-Smith's system of classification of all organisms |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society (1998) International Prize for Biology (2004) The Linnean Medal (2007) Frink Medal (2007) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Zoology |

| Institutions | King's College London, University of British Columbia, University of Oxford |

| Thesis | Organelle Development in Chlamydomonas reinhardii' (1967) |

| Website | www |

Life and career

Cavalier-Smith was born on 21 October 1942 in London. His parents were Alan Hailes Spencer and Mary Maude Cavalier-Smith. He was educated at Norwich School, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge (MA) and King's College London (PhD). He was under the supervision of Sir John Randall for his PhD thesis between 1964 and 1967; his thesis was entitled "Organelle Development in Chlamydomonas reinhardii".[2]

From 1967 to 1969, he was a guest investigator at Rockefeller University. He became Lecturer of biophysics at King's College London in 1969. He was promoted to Reader in 1982. In 1989 he was appointed Professor of botany at the University of British Columbia. In 1999, he joined the University of Oxford, becoming Professor of evolutionary biology in 2000.[3]

Awards and honours

Cavalier-Smith was elected Fellow of the Linnean Society of London (FLS) in 1980, the Institute of Biology (FIBiol) in 1983, the Royal Society of Arts (FRSA) in 1987, the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) in 1988, the Royal Society of Canada (FRSC) in 1997, and the Royal Society of London in 1998.[4] He received the International Prize for Biology from the Emperor of Japan in 2004, and the Linnean Medal for Zoology in 2007. He was appointed Fellow of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) between 1998 and 2007, and Advisor of the Integrated Microbial Biodiversity of CIFAR.[5] He won the 2007 Frink Medal of the Zoological Society of London.[3]

Contributions

Cavalier-Smith has written extensively on the taxonomy and classification of protists. One of his major contributions to biology was his proposal of a new kingdom of life: the Chromista. He also introduced a new group for primitive eukaryotes called the Chromalveolata (1981), as well as Opisthokonta (1987), Rhizaria (2002), and Excavata (2002). Though fairly well known, many of his claims have been controversial and have not gained widespread acceptance in the scientific community to date. His taxonomic revisions often lead to changes in the overall classification of all life forms.

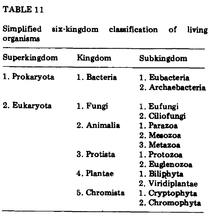

Eight kingdoms model

Cavalier-Smith's first major classification system was the division of all organisms into eight kingdoms. In 1981, he proposed that by completely revising Robert Whittaker's Five Kingdom system, there could be eight kingdoms: Bacteria, Eufungi, Ciliofungi, Animalia, Biliphyta, Viridiplantae, Cryptophyta, and Euglenozoa.[6]

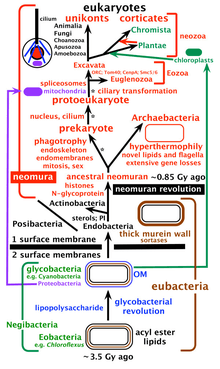

In 1993, he revised his system particularly in the light of the general acceptance of Archaebacteria as separate group from Bacteria. In addition, some protists lacking mitochondria were discovered.[7] As mitochondria were known to be the result of the endosymbiosis of a proteobacterium, it was thought that these amitochondriate eukaryotes were primitively so, marking an important step in eukaryogenesis. As a result, these amitochondriate protists were separated from the protist kingdom, giving rise to the, at the same time, superkingdom and kingdom Archezoa. This was known as the Archezoa hypothesis. The eight kingdoms became: Eubacteria, Archaebacteria, Archezoa, Protozoa, Chromista, Plantae, Fungi, and Animalia.[8]

However, kingdom Archezoa is now defunct.[9] He now assigns former members of the kingdom Archezoa to the phylum Amoebozoa.[10]

Six kingdoms models

By 1998, Cavalier-Smith had reduced the total number of kingdoms from eight to six: Animalia, Protozoa, Fungi, Plantae (including Glaucophyte, red and green algae), Chromista and Bacteria.[11] Nevertheless, he had already presented this simplified scheme for the first time on his 1981 paper[6] and endorsed it in 1983.[12]

Five of Cavalier-Smith's kingdoms are classified as eukaryotes as shown in the following scheme:

- Eubacteria

- Neomura

- Archaebacteria

- Eukaryotes

- Kingdom Protozoa

- Unikonts (heterotrophs)

- Kingdom Animalia

- Kingdom Fungi

- Bikonts (primarily photosynthetic)

- Kingdom Plantae (including red and green algae)

- Kingdom Chromista

The kingdom Animalia was divided into four subkingdoms: Radiata (phyla Porifera, Cnidaria, Placozoa, and Ctenophora), Myxozoa, Mesozoa, and Bilateria (all other animal phyla).

He created three new animal phyla: Acanthognatha (rotifers, acanthocephalans, gastrotrichs, and gnathostomulids), Brachiozoa (brachiopods and phoronids), and Lobopoda (onychophorans and tardigrades) and recognised a total of 23 animal phyla.[11]

Cavalier-Smith's 2003 classification scheme:[13]

- Unikonts

- protozoan phylum Amoebozoa (ancestrally uniciliate)

- opisthokonts

- Bikonts

- protozoan infrakingdom Rhizaria

- phylum Cercozoa

- phylum Retaria (Radiozoa and Foraminifera)

- protozoan infrakingdom Excavata

- phylum Loukozoa

- phylum Metamonada

- phylum Euglenozoa

- phylum Percolozoa

- protozoan phylum Apusozoa (Thecomonadea and Diphylleida)

- the chromalveolate clade

- kingdom Chromista (Cryptista, Heterokonta, and Haptophyta)

- protozoan infrakingdom Alveolata

- phylum Ciliophora

- phylum Miozoa (Protalveolata, Dinozoa, and Apicomplexa)

- kingdom Plantae (Viridaeplantae, Rhodophyta and Glaucophyta)

- protozoan infrakingdom Rhizaria

Seven kingdoms model

Cavalier-Smith and his collaborators revised the classification in 2015, and published it in PLOS ONE. In this scheme they reintroduced the division of prokaryotes into two kingdoms, Bacteria (=Eubacteria) and Archaea (=Archebacteria). This is based on the consensus in the Taxonomic Outline of Bacteria and Archaea (TOBA) and the Catalogue of Life.[14]

Rooting the tree of life

In 2006, Cavalier-Smith proposed that the last universal common ancestor to all life was a non-flagellate negibacterium with two membranes.[15]

References

- "Professor Dr Tom Cavalier-Smith, FRS, FRSC, Professor of Evolutionary Biology and NERC Professorial Fellow in the Department of Zoology, Oxford University". Cavali. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (1967). Organelle development in Chlamydomonas reinhardii (PhD thesis). University of London. OCLC 731219097.

- "Thomas (Tom) CAVALIER-SMITH". Debrett's. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "Awards and distinctions". Cavali. Archived from the original on 23 July 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "Thomas Cavalier-Smith". Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- Cavalier-Smith, T. (1981). "Eukaryote kingdoms: Seven or nine?". Biosystems. 14 (3–4): 461–481. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(81)90050-2. PMID 7337818.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (1987). "Eukaryotes with no mitochondria". Nature. 326 (6111): 332–333. Bibcode:1987Natur.326..332C. doi:10.1038/326332a0. PMID 3561476.

- Cavalier-Smith, T (1993). "Kingdom protozoa and its 18 phyla". Microbiological Reviews. 57 (4): 953–994. doi:10.1128/mmbr.57.4.953-994.1993. PMC 372943. PMID 8302218.

- Cavalier-Smith, T.; Chao, E. E. (1996). "Molecular phylogeny of the free-living archezoanTrepomonas agilis and the nature of the first eukaryote". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 43 (6): 551–62. Bibcode:1996JMolE..43..551C. doi:10.1007/BF02202103. PMID 8995052.

- Cavalier-Smith, T. (2004). "Only six kingdoms of life". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1545): 1251–62. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2705. PMC 1691724. PMID 15306349.

- Cavalier-Smith, T. (2007). "A revised six-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews. 73 (3): 203–66. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.x. PMID 9809012.

- Cavalier-Smith T (1983) A 6-kingdom classification and a unified phylogeny. In: Schenk HEA, Schwemmler WS, editors. Endocytobiology II: intracellular space as oligogenetic. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. pp. 1027–1034

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2003). "Protist phylogeny and the high-level classification of Protozoa". European Journal of Protistology. 39 (4): 338–348. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00002.

- Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D.; Kirk, Paul M.; Thuesen, Erik V. (2015). "A higher level classification of all living organisms". PLOS One. 10 (4): e0119248. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019248R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119248. PMC 4418965. PMID 25923521.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2006). "Rooting the tree of life by transition analyses". Biology Direct. 1: 19. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-19. PMC 1586193. PMID 16834776.