Carom billiards

Carom billiards, sometimes called carambole billiards or simply carambole, is the overarching title of a family of cue sports generally played on cloth-covered, pocketless billiard tables. In its simplest form, the object of the game is to score points or "counts" by caroming one's own cue ball off both the opponent's cue ball and the object ball on a single shot. The invention as well as the exact date of origin of carom billiards is somewhat obscure but is thought to be traceable to 18th-century France.[1]

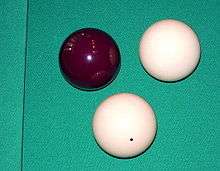

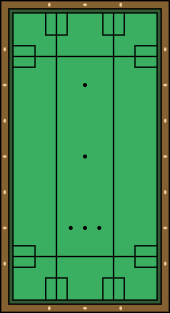

A carom billiard table and billiard balls | |

| Highest governing body | Union Mondiale de Billard (UMB) |

|---|---|

| First played | 18th century France |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | No |

| Team members | Single opponents, doubles or teams |

| Mixed gender | Yes, sometimes in separate leagues/divisions |

| Type | Indoor, table, cue sport |

| Equipment | Billiard ball, billiard table, cue stick |

| Venue | Billiard hall or home billiard room |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | No |

| World Games | 2001 – present |

There is a large array of carom billiards disciplines. Some of the more prevalent today and historically are (chronologically by apparent date of development): straight rail, cushion caroms, balkline, three-cushion billiards and artistic billiards.[1]

Carom billiards is considered obscure in the United States (being historically supplanted by pool), but is more popular in Europe, particularly France, where it originated. It is also popular in Asian countries, including Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Vietnam. The Union Mondiale de Billard (UMB) is the highest international governing body of competitive carom billiards.

Etymology

The word carom, which simply means any strike and rebound, was in use in reference to billiards by at least 1779, sometimes spelled "carrom".[1]:41 Sources differ on the origin. It has been pegged variously as a shortening of the Spanish and Portuguese word carambola, or the French word carambole, which are used to describe the red object ball. Some etymologists have suggested that carambola, in turn, was derived from a yellow-to-orange, tropical Asian fruit also known in Portuguese as a carambola (which was a corruption of the original name of the fruit, karambal in the Marathi language of India),[1][2][3] also known as star fruit. But this may simply be folk etymology, as the fruit bears no resemblance to a billiard ball, and there is no direct evidence for such a derivation.[4]

In modern French, the word carambolage means 'successive collision', currently used mainly in reference to carom or cannon shots in billiards, and to multiple-vehicle car crashes.

Equipment

Table

The billiard table used for carom billiards is a pocketless version, and is typically 3.0 by 1.5 metres (10 ft × 5 ft).[5]

Most cloth made for carom billiard tables is a type of baize that is typically dyed green, and is made from 100% worsted wool, which provides a very fast surface allowing the balls to travel with little resistance across the table bed.

The slate bed of a carom billiard table is often heated to about 5 °C (9 °F) above room temperature, which helps to keep moisture out of the cloth to aid the balls rolling and rebounding in a consistent manner, and generally makes a table play faster. A heated table is required under international tournament rules.[6] It is an especially important requirement for the games of three-cushion billiards and artistic billiards, and even local billiard halls often have this feature in countries where carom games are popular. Heating table beds is an old practice. Queen Victoria (1819–1901) had a billiard table that was heated using zinc tubes, although the aim at that time was chiefly to keep the then-used ivory balls from warping. The first use of electric heating was for an 18.2 balkline tournament held in December 1927 between Welker Cochran and Jacob Schaefer Jr.[1] The New York Times announced it with fanfare: "For the first time in the history of world's championship balkline billiards a heated table will be used ..."[1][7]

Balls

The three standard balls in most carom billiards games consist of one white cue ball, a second yellow cue ball and a third, red object ball.[1] Historically, the second cue ball was white with red or black spots to differentiate it; both types of ball sets are permitted in tournament play.[8] The balls are significantly larger and heavier than their pool or snooker counterparts, with a diameter of 61 to 61.5 millimetres (2.40 to 2.42 in), and a weight ranging between 205 and 220 grams (7.2 and 7.8 oz) with a typical weight of 210 g (7.5 oz).[9]

Billiard balls have been made from many different materials throughout the history of the game, including clay, wood, ivory, plastics (including early formulations of celluloid, Bakelite, and crystalate, and more modern phenolic resin, polyester and acrylic), and even steel. The dominant material from 1627 until the early- to mid-20th century was ivory. The search for a substitute for ivory use was not for environmental or animal-welfare concerns but based on economic motivation and fear of danger for elephant hunters. It was in part spurred on by a New York billiard table manufacturer who announced a prize of $10,000 for a substitute material. The first viable substitute was celluloid, invented by John Wesley Hyatt in 1868, but the material is volatile and highly flammable, sometimes exploding during manufacture.[1][10]

Cues

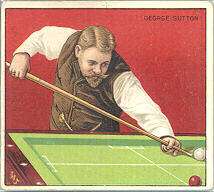

Carom billiard cues have specialized refinements making them different from the typical pool cues with which many people are more familiar. Carom cues tend to be shorter and lighter overall, with a shorter ferrule, a thicker butt and joint, a wooden joint pin (in high-end examples), and collarless wood-to-wood joint (for a one-piece cue "feel"). They have a fast, conical taper, and a smaller tip diameter as compared with pool cues. Typical carom cues are 140–140 cm (54–56 in) in length and 470–520 g (16.5–18.5 oz) in weight – lighter for straight rail, heavier for three-cushion – with a tip 11–12 mm (0.43–0.47 in) in diameter.[11] The specialization makes the cue significantly stiffer, which aids in handling the larger and heavier billiard balls as compared with pool cues. It also acts to reduce deflection (sometimes called "squirt"), which is displacement of the cue ball's path away from the parallel line formed by the cue stick's direction of travel. It is a factor that occurs every time english (side) is employed, and its effects are magnified by speed. In some carom games, deflection plays a large role because many shots require extremes of side-spin, coupled with great speed; this is a combination typically minimized as much as possible, by contrast, in pool.[12]:79, 240–1 The wood used in carom cues can vary widely, and the highest cues are handmade.

History of games

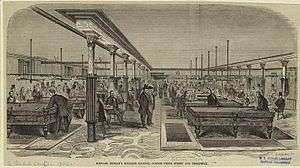

.jpg)

Straight rail

Straight rail is thought to date to the 18th century, although no exact time of origin is known. The object of straight rail is simple: one point, called a "count", is scored each time a player's cue ball makes contact with both object balls (the second cue ball and the third ball) on a single stroke. A win is achieved by reaching an agreed upon number of counts.[1]

At straight rail's inception there was no restriction on the manner of scoring. However, the technique of crotching, or freezing two balls into the corner where the rails meet—the crotch—vastly increasing counts, resulted in an 1862 rule which allowed only three counts before at least one ball had to be driven away. Techniques continued to develop which increased counts greatly despite the crotching prohibition, especially the development of a variety of "nurse" techniques. The most important of these, the rail nurse, involves the progressive nudging of the object balls down a rail, ideally moving them only a small amount on each count, keeping them close together and positioned at the end of each stroke in the same or near the same configuration such that the nurse can be replicated again and again.[1]

Straight rail is still popular in Europe, where it is considered a fine practice game for both balkline and three-cushion billiards. Additionally, Europe hosts professional competitions known as pentathlons in which straight rail is featured as one of five billiards disciplines at which players compete, the other four being 47.1 balkline, cushion caroms, 71.2 balkline, and three-cushion billiards.[1]

Straight rail was played professionally in the United States from 1873 to 1879, but is uncommon there today.[1]

Balkline

In 1879, a variant called the "champion's game" or "limited-rail" was introduced with the specific intent of frustrating the rail nurse.[1] The game employed diagonal lines at the table's corners to regions where counts were restricted.[13] Ultimately, however, despite its divergence from straight rail, the champion's game simply expanded the dimensions of the balk space defined under the existing crotch prohibition which was not sufficient to stop nursing.[1]

Balkline succeeded the champion's game, adding more rules to curb nursing techniques. In the balkline games, the entire table is divided into rectangular balk spaces, by drawing pairs of balklines lengthwise and widthwise across the table parallel from each rail. This divides the table into nine rectangular balkspaces. Such balk spaces define areas of the table surface in which a player may only score up to a threshold number of points while the object balls are within that region.[1][14][15] Additionally, rectangles are drawn where each balkline meets a rail, called anchor spaces, which developed to stop a number of nursing techniques that exploited the fact that if the object balls straddled a balkline, no count limit was in place.[1]

For the most part, the differences between one balkline game to another is defined by two measures: the spacing of the balklines and the number of points that are allowed in each balk space before at least one ball must leave the region. Generally, balkline games and their particular restrictions are given numerical names indicating both of these characteristics; the first number indicated either inches or centimeters depending on the game, and the second, after a dot or a slash, indicates the count restriction in balk spaces, which is always either one or two. For example, in 18.2 balkline, one of the more prominent balkline games and of US origin, the name indicates that balklines are drawn 18 inches distant from each rail, and only two counts are allowed in a balk space before a ball must leave.[1] By contrast, in 71.2 balkline, of French invention, lines are drawn 71 centimeters distant from each rail, also with a two-count restriction for balk spaces.[16] In the heavily French-influenced lingo of carom billiards, the first of these shots is called the entrée and the second the dedans; in one-count balkline games, the one permitted count is called dedans.

In its various incarnations, balkline was the predominant carom discipline from 1883 to the 1930s, when it was overtaken by three-cushion billiards and pool. Balkline is still popular in Europe and the Far East.[1]

One-cushion

One-cushion carom, or simply cushion carom, also arose in the late 1860s as another alternative to the repetitive play of straight rail, inspired by an early variant of English billiards. The object of the game is to score cushion caroms, meaning a carom off of both object balls with at least one rail cushion being struck before the hit on the second object ball. One-cushion carom is still popular in Europe.[1][17]

Three-cushion

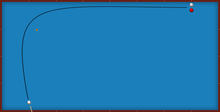

In three-cushion carom, the object is to carom off both object balls with at least three rail cushions being contacted before the contact of the cue ball with the second object ball.

Three-cushion is a very difficult game. Averaging one point per inning is professional-level play, and averaging 1.5 to 2 is world-class play. An average of one means that for every turn at the table, a player makes 1 point and misses once, thus making a point on 50% of his or her shots.

Wayman C. McCreery of St. Louis, Missouri, is credited with popularizing the game in the 1870s.[1][18] At least one publication categorically states he invented the game as well.[19] The first three-cushion billiards tournament took place January 14–31, 1878, in St. Louis, with McCreery a participant and Leon Magnus the winner. The high run for the tournament was just 6 points, and the high average a 0.75.[20] The game was infrequently played, with many top carom players of the era voicing their dislike of it, until the 1907 introduction of the Lambert Trophy.[1][21] By 1924, three-cushion had become so popular that two giants in other billiard disciplines agreed to take up the game especially for a challenge match. On September 22, 1924, Willie Hoppe, the world's balkline champion (who later took up three-cushion with a passion), and Ralph Greenleaf, the world's straight pool title holder, played a well advertised, multi-day, match to 600 points. Hoppe was the eventual winner with a final score in of 600–527.

Three-cushion billiards retains great popularity in parts of Europe, Asia, and Latin America,[1] and is the most popular carom billiards game played in the US today, where pool is far more widespread. The principal governing body of the sport is the Union Mondiale de Billard (UMB). It had been staging world three-cushion championships since the late 1920s.[22] The International Olympic Committee-recognized World Pool-Billiard Association (WPA) cooperates with the UMB to keep their rulesets synchronized.

Artistic billiards

In artistic billiards players compete at performing 76 preset shots of varying difficulty. Each set shot has a maximum point value assigned for perfect execution, ranging from a 4-point minimum for lowest level difficulty shots, and climbing to an 11-point maximum for shots deemed highest in difficulty level. There is a total of 500 points available to a player.[1]

Each shot in an artistic billiards match is played from a well-defined position (in some venues within an exacting two millimeter tolerance), and each shot must unfold in an established manner. Players are allowed three attempts at each shot. In general, the shots making up the game, even 4-point shots, require a high degree of skill, devoted practice and specialized knowledge to perform.[1][23]

World title competition first started in 1986 and required the use of ivory balls. However, this requirement was dropped in 1990. The highest score ever achieved in competition overall is 427 set by Walter Bax on March 12, 2006, at a competition held in Deurne, Belgium, beating his own previous record of 425.[24] The game is played predominantly in western Europe, especially in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.[1][23]

Competition disciplines

- Triathlon: Straight rail, balkline and one-cushion; or balkline, one-cushion, and three-cushion; the latter format is used in the ANAG Billiard Cup[25]

- Pentathlon: Straight rail, balkline (47.2 and 71.2), one-cushion, and three-cushion.

In popular culture

- Carom billiards appear in the film Le Cercle Rouge (1970).

References

- Shamos, Michael Ian (1993). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York: Lyons & Burford. pp. 10, 15–17, 26, 41–42, 46, 53, 72<--Probably 79 in 1999 ver.-->, 82, 86–87, 92, 104, 115, 157–158, 196, 229, 232–233, 244–245. ISBN 1-55821-219-1.

- Douglas Harper (2001). Carom - Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- Lexico Publishing Group, LLC (2006). Carom - Dictionary.com. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- Benbow, T. J., ed. (2007) [1997]. Oxford English Dictionary (2nd (CD-ROM ver. 3.1) ed.). Oxford University Press. "carambole, n.", etymology. ISBN 978-0-19-522217-3.

Derivation unknown. As the word is in [Portuguese] identical in form with [the] prec[eding, the carambola fruit], suggestions as to their identity have been made, but without any evidence.

- "World Rules of Carom Billiard" (PDF). Union Mondiale de Billard. Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium. 1 January 1989. Chapter II ("Equipment"), Article 11 , Section 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- "World Rules of Carom Billiard" (PDF). Union Mondiale de Billard. Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium. 1 January 1989. Chapter II ("Equipment"), Article 11 , Section 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- The New York Times (16 December 1927). "To Heat Table for First Time in World Title Billiard Match". Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Applied Regulations Affecting the Billiard Cloth and the Balls" (PDF). World Organization Rules. Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium: Union Mondiale de Billard. 1989-01-01. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- "World Rules of Carom Billiard" (PDF). Union Mondiale de Billard. Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium. 1 January 1989. Chapter II ("Equipment"), Article 12 ("Balls, Chalk"), Section 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 5 March 2007. The cited document has a "cm" for "mm" typographical error.

- The New York Times (16 September 1875). "Explosive Teeth". Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- Kilby, Ronald (May 23, 2009). "So What's a Carom Cue?". CaromCues.com. Medford, Oregon: Kilby Cues. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- Shamos, Mike (1999). The New Illustrated Encyclopedia of Billiards. New York: Lyons Press. ISBN 1-55821-797-5.

- The New York Times (10 November 1879). "Billiards Under New Rules: A Tournament in Which Rail Play Will be Restricted – The Programme". Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- Neil Cohen, ed. (1994). The Everything You Want to Know About Sport Encyclopedia. Toronto: Bantam Books. p. 79. ISBN 0-553-48166-5.

- Grolier Inc., ed. (1998). The Encyclopedia Americana. Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier Incorporated. p. 746. ISBN 0-7172-0131-7.

- Kieran, John (December 7, 1937). "Sports of the Times; Reg. U. S. Pat. Off". The New York Times. p. 35. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- Hoyle, Edmond; et al. (1907). Hoyle's Games – Autograph Edition. New York: A. L. Burt Company. p. 41.

- The New York Times (September 21, 1902). "Billiards Players Busy". Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- Thomas, Augustus (1922). The Print of My Remembrance. New York / London: C. Scribner's Sons. p. 117.

- Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company (1909). Modern Billiards. New York: Trow Directory. p. 333. Retrieved May 27, 2009 – via Google Books.

- The New York Times (January 6, 1911). "Magnus Plays Poor Billiards". Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- "List of UMB World 3-cushion Champions". Archived from the original on 2009-02-04.

- Martin Škrášek (2000). What's Artistic Billiard? Archived 2007-02-20 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2006

- "Walter Bax vestigt nieuw Wereldrecord ("Walter Bax establishes a New World Record")" (in Dutch). biljartteam TOERIST - ARO. Archived from the original on October 27, 2006. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- "News and Events". www.anagbilliardcup.cz.

External links

![]()

- Union Mondiale de Billard — world tournament sanctioning body

- Archival Billiard Resource

- Kozoom.com: Online Carom Billiard Magazine live streaming all UMB events

- Animation showing the "rail nurse" with a description

- USBA 3-Cushion Billiard Rules USBA 3-Cushion Billiard Rules

- Billiard Diamond System Calculator simulates cue ball path on billiard table