Candle

A candle is an ignitable wick embedded in wax, or another flammable solid substance such as tallow, that provides light, and in some cases, a fragrance. A candle can also provide heat or a method of keeping time.

A person who makes candles is traditionally known as a chandler.[1] Various devices have been invented to hold candles, from simple tabletop candlesticks, also known as candle holders, to elaborate candelabra and chandeliers.[2]

For a candle to burn, a heat source (commonly a naked flame from a match or lighter) is used to light the candle's wick, which melts and vaporizes a small amount of fuel (the wax). Once vaporized, the fuel combines with oxygen in the atmosphere to ignite and form a constant flame. This flame provides sufficient heat to keep the candle burning via a self-sustaining chain of events: the heat of the flame melts the top of the mass of solid fuel; the liquefied fuel then moves upward through the wick via capillary action; the liquefied fuel finally vaporizes to burn within the candle's flame.

As the fuel (wax) is melted and burned, the candle becomes shorter. Portions of the wick that are not emitting vaporized fuel are consumed in the flame. The incineration of the wick limits the length of the exposed portion of the wick, thus maintaining a constant burning temperature and rate of fuel consumption. Some wicks require regular trimming with scissors (or a specialized wick trimmer), usually to about one-quarter inch (~0.7 cm), to promote slower, steady burning, and also to prevent smoking. Special candle-scissors called "snuffers" were produced for this purpose in the 20th century and were often combined with an extinguisher. In modern candles, the wick is constructed so that it curves over as it burns. This ensures that the end of the wick gets oxygen and is then consumed by fire—a self-trimming wick.[3]

Etymology

The word candle comes from Middle English candel, from Old English and from Anglo-Norman candele, both from Latin candēla, from candēre, to shine.[4]

History

Prior to the candle, people used oil lamps in which a lit wick rested in a container of liquid oil. Liquid oil lamps had a tendency to spill, and the wick had to be advanced by hand. Romans began making true dipped candles from tallow, beginning around 500 BC.[5] European candles of antiquity were made from various forms of natural fat, tallow, and wax. In Ancient Rome, candles were made of tallow due to the prohibitive cost of beeswax.[6] It is possible that they also existed in Ancient Greece, but imprecise terminology makes it difficult to determine.[6] The earliest surviving candles originated in Han China around 200 BC. These early Chinese candles were made from whale fat.

During the Middle Ages, tallow candles were most commonly used. By the 13th century, candle making had become a guild craft in England and France. The candle makers (chandlers) went from house to house making candles from the kitchen fats saved for that purpose, or made and sold their own candles from small candle shops.[7] Beeswax, compared to animal-based tallow, burned cleanly, without smoky flame. Beeswax candles were expensive, and relatively few people could afford to burn them in their homes in medieval Europe. However, they were widely used for church ceremonies.[8]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, spermaceti, a waxy substance produced by the sperm whale, was used to produce a superior candle that burned longer, brighter and gave off no offensive smell.[9] Later in the 18th century, colza oil and rapeseed oil came into use as much cheaper substitutes.

Modern era

The manufacture of candles became an industrialized mass market in the mid 19th century. In 1834, Joseph Morgan,[10] a pewterer from Manchester, England, patented a machine that revolutionised candle making. It allowed for continuous production of molded candles by using a cylinder with a moveable piston to eject candles as they solidified. This more efficient mechanized production produced about 1,500 candles per hour. This allowed candles to be an affordable commodity for the masses.[11] Candlemakers also began to fashion wicks out of tightly braided (rather than simply twisted) strands of cotton. This technique makes wicks curl over as they burn, maintaining the height of the wick and therefore the flame. Because much of the excess wick is incinerated, these are referred to as "self-trimming" or "self-consuming" wicks.[12]

In the mid-1850s, James Young succeeded in distilling paraffin wax from coal and oil shales at Bathgate in West Lothian and developed a commercially viable method of production.[13] Paraffin could be used to make inexpensive candles of high quality. It was a bluish-white wax, which burned cleanly and left no unpleasant odor, unlike tallow candles. By the end of the 19th century, candles were made from paraffin wax and stearic acid.

By the late 19th century, Price's Candles, based in London, was the largest candle manufacturer in the world.[14] Founded by William Wilson in 1830,[15] the company pioneered the implementation of the technique of steam distillation, and was thus able to manufacture candles from a wide range of raw materials, including skin fat, bone fat, fish oil and industrial greases.

Despite advances in candle making, the candle industry declined rapidly upon the introduction of superior methods of lighting, including kerosene and lamps and the 1879 invention of the incandescent light bulb. From this point on, candles came to be marketed as more of a decorative item.

Use

.jpg)

Before the invention of electric lighting, candles and oil lamps were commonly used for illumination. In areas without electricity, they are still used routinely. Until the 20th century, candles were more common in northern Europe. In southern Europe and the Mediterranean, oil lamps predominated.

In the developed world today, candles are used mainly for their aesthetic value and scent, particularly to set a soft, warm, or romantic ambiance, for emergency lighting during electrical power failures, and for religious or ritual purposes.

Other uses

With the fairly consistent and measurable burning of a candle, a common use of candles was to tell the time. The candle designed for this purpose might have time measurements, usually in hours, marked along the wax. The Song dynasty in China (960–1279) used candle clocks.[16]

By the 18th century, candle clocks were being made with weights set into the sides of the candle. As the candle melted, the weights fell off and made a noise as they fell into a bowl.

In the days leading to Christmas, some people burn a candle a set amount to represent each day, as marked on the candle. The type of candle used in this way is called the Advent candle,[17] although this term is also used to refer to a candle that decorates an Advent wreath.

Components

Wax

.jpg)

For most of recorded history candles were made from tallow (rendered from beef or mutton-fat) or beeswax. From the mid 1800s they were also made from spermaceti, a waxy substance derived from the Sperm whale, which in turn spurred demand for the substance. Candles were also made from stearin (initially manufactured from animal fats but now produced almost exclusively from palm waxes).[18][19] Today, most candles are made from paraffin wax, a byproduct of petroleum refining.[20]

Candles can also be made from microcrystalline wax, beeswax (a byproduct of honey collection), gel (a mixture of polymer and mineral oil),[21] or some plant waxes (generally palm, carnauba, bayberry, or soybean wax).

The size of the flame and corresponding rate of burning is controlled largely by the candle wick.

Production methods utilize extrusion moulding.[20] More traditional production methods entail melting the solid fuel by the controlled application of heat. The liquid is then poured into a mould, or a wick is repeatedly immersed in the liquid to create a dipped tapered candle. Often fragrance oils, essential oils or aniline-based dye is added.

Wick

A candle wick works by capillary action, drawing ("wicking") the melted wax or fuel up to the flame. When the liquid fuel reaches the flame, it vaporizes and combusts. The candle wick influences how the candle burns. Important characteristics of the wick include diameter, stiffness, fire-resistance, and tethering.

A candle wick is a piece of string or cord that holds the flame of a candle. Commercial wicks are made from braided cotton. The wick's capillarity determines the rate at which the melted hydrocarbon is conveyed to the flame. If the capillarity is too great, the molten wax streams down the side of the candle. Wicks are often infused with a variety of chemicals to modify their burning characteristics. For example, it is usually desirable that the wick not glow after the flame is extinguished. Typical agents are ammonium nitrate and ammonium sulfate.[20]

Characteristics

Light

Based on measurements of a taper-type, paraffin wax candle, a modern candle typically burns at a steady rate of about 0.1 g/min, releasing heat at roughly 80 W.[22] The light produced is about 13 lumens, for a luminous efficacy of about 0.16 lumens per watt (luminous efficacy of a source) – almost a hundred times lower than an incandescent light bulb.

The luminous intensity of a typical candle is approximately one candela. The SI unit, candela, was in fact based on an older unit called the candlepower, which represented the luminous intensity emitted by a candle made to particular specifications (a "standard candle"). The modern unit is defined in a more precise and repeatable way, but was chosen such that a candle's luminous intensity is still about one candela.

Temperature

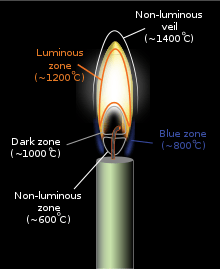

The hottest part of a candle flame is just above the very dull blue part to one side of the flame, at the base. At this point, the flame is about 1,400 °C (2,550 °F). However note that this part of the flame is very small and releases little heat energy. The blue color is due to chemiluminescence, while the visible yellow color is due to radiative emission from hot soot particles. The soot is formed through a series of complex chemical reactions, leading from the fuel molecule through molecular growth, until multi-carbon ring compounds are formed. The thermal structure of a flame is complex, hundreds of degrees over very short distances leading to extremely steep temperature gradients. On average, the flame temperature is about 1,000 °C (1,830 °F).[23] The color temperature is approximately 1000 K.

Candle flame

A candle flame is formed because wax vaporizes on burning. A candle flame is widely recognized as having between three and five regions or "zones":

- Zone I - this is the non-luminous, lowest, and coolest part of the candle flame. It is located around the base of the wick where there is insufficient oxygen for fuel to burn. Temperatures are around 600 °C (1,112 °F).

- Zone II - this is the blue zone which surrounds the base of the flame. Here the supply of oxygen is plentiful, and the fuel burns clean and blue. It is heat from this zone which causes the wax to melt. Temperatures are around 800 °C (1,470 °F)

- Zone III - the dark zone is a region directly above the wick containing unburnt wax. Pyrolysis takes place here. Temperature is around 1,000 °C (1,830 °F)

- Zone IV - the middle or luminous zone is yellow/ white and is located above the dark zone. It is the brightest zone, but not the hottest. It is an oxygen-depleted zone with insufficient oxygen to burn all of the wax vapor rising from below it resulting in only partial combustion. The zone also contains unburnt carbon particles. Temperature is around 1,200 °C (2,190 °F).

- Zone V - The non-luminous outer zone or veil surrounds Zone IV. Here the flame is at its hottest, at around 1,400 °C (2,550 °F), and complete combustion occurs. It is light blue in color though most of it is invisible.[24][25]

The main determinant of the height of a candle flame is the diameter of the wick. This is evidenced in tealights where the wick is very thin and the flame is very small. Candles whose main purpose is illumination use a much thicker wick.[26]

History of study

One of Michael Faraday's significant works was The Chemical History of a Candle, where he gives an in-depth analysis of the evolutionary development, workings and science of candles.[27]

Hazards

According to the U.S. National Fire Protection Association, candles are a leading source of residential fires in the United States with almost 10% of civilian injuries and 6% of fatalities from fire attributed to candles.[28] A candle flame that is longer than its laminar smoke point will emit soot.[29] Proper wick trimming will reduce soot emissions from most candles.

The liquid wax is hot and can cause skin burns, but the amount and temperature are generally rather limited and the burns are seldom serious. The best way to avoid getting burned from splashed wax is to use a candle snuffer instead of blowing on the flame. A candle snuffer is usually a small metal cup on the end of a long handle. Placing the snuffer over the flame cuts off the oxygen supply. Snuffers were common in the home when candles were the main source of lighting before electric lights were available. Ornate snuffers, often combined with a taper for lighting, are still found in those churches which regularly use large candles.

Glass candle-holders are sometimes cracked by thermal shock from the candle flame, particularly when the candle burns down to the end. When burning candles in glass holders or jars, users should avoid lighting candles with chipped or cracked containers, and stop use once 1/2 inch or less of wax remains.

A former worry regarding the safety of candles was that a lead core was used in the wicks to keep them upright in container candles. Without a stiff core, the wicks of a container candle could sag and drown in the deep wax pool. Concerns rose that the lead in these wicks would vaporize during the burning process, releasing lead vapors — a known health and developmental hazard. Lead core wicks have not been common since the 1970s. Today, most metal-cored wicks use zinc or a zinc alloy, which has become the industry standard. Wicks made from specially treated paper and cotton are also available.

Regulation

International markets have developed a range of standards and regulations to ensure compliance, while maintaining and improving safety, including:

- Europe: GPSD, EN 15493, EN 15494, EN 15426, EN 14059, REACH, RAL-GZ 041 Candles (Germany), French Decree 91-1175

- United States: ASTM F2058, ASTM F2179, ASTM F2417, ASTM F2601, ASTM F2326 ( all are federal and applies in all 50 states), California Proposition 65 (California only), CONEG (New England and New York states only)

- China: QB/T 2119 Basic Candle, QB/T 2902 Art Candle, QB/T 2903 Jar Candle, GB/T 22256 Jelly Candle

Accessories

Candle holders

Decorative candleholders, especially those shaped as a pedestal, are called candlesticks; if multiple candle tapers are held, the term candelabrum is also used. The root form of chandelier is from the word for candle, but now usually refers to an electric fixture. The word chandelier is sometimes now used to describe a hanging fixture designed to hold multiple tapers.

Many candle holders use a friction-tight socket to keep the candle upright. In this case, a candle that is slightly too wide will not fit in the holder, and a candle that is slightly too narrow will wobble. Candles that are too big can be trimmed to fit with a knife; candles that are too small can be fitted with aluminium foil. Traditionally, the candle and candle holders were made in the same place, so they were appropriately sized, but international trade has combined the modern candle with existing holders, which makes the ill-fitting candle more common. This friction tight socket is only needed for the federals and the tapers. For tea light candles, there is a variety of candle holders, including small glass holders and elaborate multi-candle stands. The same is true for votives. Wall sconces are available for tea light and votive candles. For pillar-type candles, the assortment of candle holders is broad. A fireproof plate, such as a glass plate or small mirror, can be a candle holder for a pillar-style candle. A pedestal of any kind, with the appropriate-sized fireproof top, is another option. A large glass bowl with a large flat bottom and tall mostly vertical curved sides is called a hurricane. The pillar-style candle is placed at the bottom center of the hurricane. A hurricane on a pedestal is sometimes sold as a unit.

A bobèche is a drip-catching ring, which may also be affixed to a candle holder, or used independently of one. Bobèches can range from ornate metal or glass to simple plastic, cardboard, or wax paper. Use of paper or plastic bobèches is common at events where candles are distributed to a crowd or audience, such as Christmas carolers or people at other concerts/festivals.

Candle followers

These are glass or metal tubes with an internal stricture partway along, which sit around the top of a lit candle. As the candle burns, the wax melts and the follower holds the melted wax in, whilst the stricture rests on the topmost solid portion of wax. Candle followers are often deliberately heavy or weighted to ensure they move down as the candle burns lower, maintaining a seal and preventing wax escape. The purpose of a candle follower is threefold:

- To contain the melted wax, making the candle more efficient, avoiding mess, and producing a more even burn.

- As a decoration, either due to the ornate nature of the device, or (in the case of a glass follower) through light dispersion or colouration.

- If necessary, to shield the flame from wind.

Candle followers are often found in churches on altar candles.

Candle snuffers

Candle snuffers are instruments used to extinguish burning candles by smothering the flame with a small metal cup that is suspended from a long handle, and thus depriving it of oxygen. An older meaning refers to a scissor-like tool used to trim the wick of a candle. With skill, this could be done without extinguishing the flame. The instrument now known as a candle snuffer was formerly called an "extinguisher" or "douter".

See also

References

- "Chandler". The Free Dictionary By Farlex. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- "chandelier". The Free Dictionary By Farlex. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- European Candle Association FAQ Archived 2012-01-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Candle". The Free Dictionary By Farlex. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- "Candles, Roman, 500 BCE". Smith College Museum.

- Forbes, R J (1955). Studies in Ancient technology. pp. 139–40. ISBN 978-9004006263. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "History of candles". National Candle Association. Archived from the original on May 17, 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-19.

- "history of candle". national candle association.

- Shillito, M. Larry; David J. De Marle (1992). Value: Its Measurement, Design, and Management. Wiley-IEEE. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-471-52738-1.

- "Joseph Morgan and Son". Graces Guide.

- Phillips, Gordon (1999). Seven Centuries of Light: The Tallow Chandlers Company. Book Production Consultants. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-85757-064-9.

- "A Brief History of Candles". Archived from the original on 2013-03-18. Retrieved 2015-07-06.

- Golan, Tal (2004). Laws of Men and Laws of Nature: The History of Scientific Expert Testimony in England and America. Harvard University Press. pp. 89–91. ISBN 978-0674012868.

- Geoff Marshall (2013). London's Industrial Heritage. The History Press. ISBN 9780752492391.

- Ball, Michael; David Sunderland (2001). An Economic History of London, 1800-1914. Routledge. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-0415246910.

- Whitrow, G. J. (1989). Time in History: Views of Time from Prehistory to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-19-285211-3. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015.

- Geddes, Gordon; Jane Griffiths (2002). Christianity. Heinemann. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-435-30693-9.

- "Using stearic acid or stearin in candlemaking". happynews.com. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- "Stearic acid (stearin)". howtomakecandles.info. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Franz Willhöft and Fredrick Horn "Candles" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2000, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a05_029

- Camp, William R.; Vollenweider, Jeffrey L.; Schutz, Wendy J. (12 October 1999). "Scented candle gel". United States Patent 5,964,905.

- Hamins, Anthony; Bundy, Matthew; Dillon, Scott E. (November 2005). "Characterization of Candle Flames" (PDF). Journal of Fire Protection Engineering. 15 (4): 277. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.548.3798. doi:10.1177/1042391505053163.

- "On Fire – Background Essay". PBS LearningMedia. PBS and WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- Allen R. White (2013). "FTIR STUDY OF COMBUSTION SPECIES IN SEVERAL REGIONS OF A CANDLE FLAME". Ohio State University. hdl:1811/55436.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training. "Science: Textbook for Class VIII". Publication Department, 2010, p.72.

- Sunderland, P.B.; Quintiere, J.G.; Tabaka, G.A.; Lian, D.; Chiu, C.-W. (6 October 2010). "Analysis and measurement of candle flame shapes" (PDF). Proceedings of the Combustion Institute. 33: 2489–2496. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- "Internet History Sourcebooks". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- John Hall, NFPA 2009, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2013-01-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- K.M. Allan, J.R. Kaminski, J.C. Bertrand, J. Head, Peter B. Sunderland, Laminar Smoke Points of Wax Candles, Combustion Science and Technology 181 (2009) 800–811.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Candles |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Candles. |

- National Candle Association of the U.S.

- The Chemical History of a Candle by Michael Faraday

- Association of European Candlemakers(AECM)

- European Candle Association (ECA)

- Latin American Candle Manufacturers Association (ALAFAVE)

- Guide To Candle Safety At Home - Osmology