Excalibur

Excalibur (/ɛkˈskælɪbər/) is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone (the proof of Arthur's lineage) are sometimes said to be the same weapon, but in most versions they are considered separate. Excalibur was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. In Welsh, it is called Caledfwlch; in Cornish, Calesvol (in Modern Cornish: Kalesvolgh); in Breton, Kaledvoulc'h; and in Latin, Caliburnus.

| Excalibur | |

|---|---|

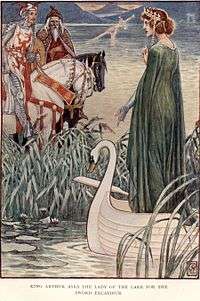

Excalibur the Sword by Howard Pyle (1903) | |

| Plot element from Arthurian legend | |

| In-story information | |

| Type | Legendary sword |

| Element of stories featuring | King Arthur, Merlin, Lady of the Lake |

Forms and etymologies

The name Excalibur ultimately derives from the Welsh Caledfwlch (and Breton Kaledvoulc'h, Middle Cornish Calesvol), which is a compound of caled "hard" and bwlch "breach, cleft".[1] Caledfwlch appears in several early Welsh works, including the prose tale Culhwch and Olwen. The name was later used in Welsh adaptations of foreign material such as the Bruts (chronicles), which were based on Geoffrey of Monmouth. It is often considered to be related to the phonetically similar Caladbolg, a sword borne by several figures from Irish mythology, although a borrowing of Caledfwlch from Irish Caladbolg has been considered unlikely by Rachel Bromwich and D. Simon Evans. They suggest instead that both names "may have similarly arisen at a very early date as generic names for a sword". This sword then became exclusively the property of Arthur in the British tradition.[1][2]

Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain, c. 1136), Latinised the name of Arthur's sword as Caliburnus (potentially influenced by the Medieval Latin spelling calibs of Classical Latin chalybs, from Greek chályps [χάλυψ] "steel"). Most Celticists consider Geoffrey's Caliburnus to be derivative of a lost Old Welsh text in which bwlch (Old Welsh bulc[h]) had not yet been lenited to fwlch (Middle Welsh vwlch or uwlch).[3][4][1] In the late 15th/early 16th-century Middle Cornish play Beunans Ke, Arthur's sword is called Calesvol, which is etymologically an exact Middle Cornish cognate of the Welsh Caledfwlch. It is unclear if the name was borrowed from the Welsh (if so, it must have been an early loan, for phonological reasons), or represents an early, pan-Brittonic traditional name for Arthur's sword.[5]

In Old French sources this then became Escalibor, Excalibor, and finally the familiar Excalibur. Geoffrey Gaimar, in his Old French L'Estoire des Engleis (1134-1140), mentions Arthur and his sword: "this Constantine was the nephew of Arthur, who had the sword Caliburc" ("Cil Costentin, li niès Artur, Ki out l'espée Caliburc").[6][7] In Wace's Roman de Brut (c. 1150-1155), an Old French translation and versification of Geoffrey's Historia, the sword is called Calabrum, Callibourc, Chalabrun, and Calabrun (with variant spellings such as Chalabrum, Calibore, Callibor, Caliborne, Calliborc, and Escaliborc, found in various manuscripts of the Brut).[8]

In Chrétien de Troyes' late 12th-century Old French Perceval, Arthur's knight Gawain carries the sword Escalibor and it is stated, "for at his belt hung Escalibor, the finest sword that there was, which sliced through iron as through wood"[9] ("Qu'il avoit cainte Escalibor, la meillor espee qui fust, qu'ele trenche fer come fust"[10]). This statement was probably picked up by the author of the Estoire Merlin, or Vulgate Merlin, where the author (who was fond of fanciful folk etymologies) asserts that Escalibor "is a Hebrew name which means in French 'cuts iron, steel, and wood'"[11] ("c'est non Ebrieu qui dist en franchois trenche fer & achier et fust"; note that the word for "steel" here, achier, also means "blade" or "sword" and comes from medieval Latin aciarium, a derivative of acies "sharp", so there is no direct connection with Latin chalybs in this etymology). It is from this fanciful etymological musing that Thomas Malory got the notion that Excalibur meant "cut steel"[12] ("'the name of it,' said the lady, 'is Excalibur, that is as moche to say, as Cut stele'").

Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone

_(14801002423).jpg)

In Arthurian romance, a number of explanations are given for Arthur's possession of Excalibur. In Robert de Boron's Merlin, the first tale to mention the "sword in the stone" motif c. 1200, Arthur obtained the British throne by pulling a sword from an anvil sitting atop a stone that appeared in a churchyard on Christmas Eve.[13] In this account, as foretold by Merlin, the act could not be performed except by "the true king," meaning the divinely appointed king or true heir of Uther Pendragon. As Malory related in his most famous English-language version of the Arthurian tales, the 15th-century Le Morte d'Arthur: "Whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone and anvil, is rightwise king born."[14][note 1] After many of the gathered nobles try and fail to complete Merlin's challenge, the teenage Arthur (who up to this point had believed himself to be son of Sir Ector, not Uther's son, and went there as Sir Kay's squire) does this feat effortlessly by accident and then repeats it publicly.

The identity of this sword as Excalibur is made explicit in the Prose Merlin, part of the Lancelot-Grail cycle of French romances (the Vulgate Cycle).[15] In the Vulgate Mort Artu, when Arthur at the brink of death he orders Griflet to throw the sword into the enchanted lake; after two failed attempts (as he felt such a great sword should not be thrown away), Griflet finally complies with the wounded king's request and a hand emerges from the lake to catch it. This tale becomes attached to Bedivere instead of Griflet in Malory and the English tradition.[16] However, in the Post-Vulgate Cycle and consequently Malory, early in his reign Arthur breaks the Sword from the Stone while in combat against King Pellinore, and then is given Excalibur by a Lady of the Lake in exchange for a later boon for her (some time later, she arrives at Arthur's court to demand the head of Balin). Malory records both versions of the legend in his Le Morte d'Arthur, naming both swords as Excalibur.[17][18]

Other roles and attributes

Welsh stories

In Welsh legends, Arthur's sword is known as Caledfwlch. In Culhwch and Olwen, it is one of Arthur's most valuable possessions and is used by Arthur's warrior Llenlleawg the Irishman to kill the Irish king Diwrnach while stealing his magical cauldron. Irish mythology mentions a weapon Caladbolg, the sword of Fergus mac Róich, which was also known for its incredible power and was carried by some of Ireland's greatest heroes. The name, which can also mean "hard cleft" in Irish, appears in the plural, caladbuilc, as a generic term for "great swords" in Togail Troi ("The Destruction of Troy"), a 10th-century Irish translation of the classical tale.[19][20]

Though not named as Caledfwlch, Arthur's sword is described vividly in The Dream of Rhonabwy, one of the tales associated with the Mabinogion (as translated by Jeffrey Gantz): "Then they heard Cadwr Earl of Cornwall being summoned, and saw him rise with Arthur's sword in his hand, with a design of two chimeras on the golden hilt; when the sword was unsheathed what was seen from the mouths of the two chimeras was like two flames of fire, so dreadful that it was not easy for anyone to look."[21]

Other versions

Geoffrey's Historia is the first non-Welsh source to speak of the sword. Geoffrey says the sword was forged in Avalon and Latinises the name "Caledfwlch" as Caliburnus. When his influential pseudo-history made it to Continental Europe, writers altered the name further until it finally took on the popular form Excalibur (various spellings in the medieval Arthurian romance and chronicle tradition include: Calabrun, Calabrum, Calibourne, Callibourc, Calliborc, Calibourch, Escaliborc, and Escalibor[22]).

The legend was expanded upon in the Vulgate Cycle and in the Post-Vulgate Cycle which emerged in its wake. Both included the Prose Merlin, but the Post-Vulgate authors left out the Merlin continuation from the earlier cycle, choosing to add an original account of Arthur's early days including a new origin for Excalibur. In many versions, Excalibur's blade was engraved with phrases on opposite sides: "Take me up" and "Cast me away" (or similar). In addition, when Excalibur was first drawn, in the first battle testing Arthur's sovereignty, its blade blinded his enemies.[note 2] In several French works, such as Chrétien's Perceval and the Vulgate Lancelot, Excalibur is used by Gawain, Arthur's nephew and one of his best knights. This is in contrast to later versions, where Excalibur belongs solely to Arthur.

In some tellings, Excalibur's scabbard was also said to have powers of its own, as any wounds received while wearing the scabbard would not bleed at all, thus preventing the death of the wearer. For this reason, Merlin chides Arthur for preferring the sword over the scabbard, saying that the latter was the greater treasure. In the later romance tradition, including Le Morte d'Arthur, the scabbard is stolen from Arthur by his half-sister Morgan le Fay in revenge for the death of her beloved Accolon during the Fake Excalibur plot and thrown into a lake, never to be found again. This act later enables the death of Arthur in his final battle.

The challenge of drawing a sword from a stone also appears in the later Arthurian stories of Galahad, whose achievement of the task indicates that he is destined to find the Holy Grail as foretold by Merlin. As told by Malory, this weapon (known as the Adventurous Sword among other names) had also come from Avalon; it had been originally wielded by Balin and eventually was used by Lancelot to give Gawain mortal wound in their duel. In Perlesvaus, Lancelot pulls other weapons from stone on two occasions.

Arthur's other weapons

Other weapons have been associated with Arthur. Welsh tradition also knew of a dagger named Carnwennan and a spear named Rhongomyniad that belonged to him. Carnwennan ("little white-hilt") first appears in Culhwch and Olwen, where Arthur uses it to slice the witch Orddu in half.[1][23] Rhongomyniad ("spear" + "striker, slayer") is also mentioned in Culhwch, although only in passing; it appears as simply Ron ("spear") in Geoffrey's Historia. Geoffrey also names Arthur's shield as Pridwen, but in Culhwch, Prydwen ("fair face") is the name of Arthur's ship while his shield is named Wynebgwrthucher ("face of evening").[1][3]

The Alliterative Morte Arthure, a Middle English poem, mentions Clarent, a sword of peace meant for knighting and ceremonies as opposed to battle, which Mordred stole and then used to kill Arthur at Camlann.[24] The Prose Lancelot of the Vulgate Cycle mentions a sword called Seure (Sequence), or Secace in some manuscripts, which belonged to the king but was used by Lancelot in one battle.[25]

Similar weapons

In Welsh mythology, the Dyrnwyn ("White-Hilt"), one of the Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain, is said to be a powerful sword belonging to Rhydderch Hael,[26] one of the Three Generous Men of Britain mentioned in the Welsh Triads. When drawn by a worthy or well-born man, the entire blade would blaze with fire. Rhydderch was never reluctant to hand the weapon to anyone, hence his nickname Hael "the Generous", but the recipients, as soon as they had learned of its peculiar properties, always rejected the sword.

There are other similar weapons described in other mythologies. In particular, Claíomh Solais, which is an Irish term meaning "Sword of Light", or "Shining Sword", appears in a number of orally transmitted Irish folk-tales. The Sword in the Stone has an analogue in some versions of the story of Sigurd, whose father, Sigmund, draws the sword Gram out of the tree Barnstokkr where it is embedded by the Norse god Odin. A sword in the stone legend is also associated with the 12th-century Italian Saint Galgano.

Notes

- This version also appears in the 1938 Arthurian novel The Sword in the Stone by British author T. H. White, and the Disney adaptation; they both quote the line from Thomas Malory in the 15th century.

- Malory writes in the Winchester Manuscript: "thenne he drewe his swerd Excalibur, but it was so breyght in his enemyes eyen that it gaf light lyke thirty torchys." Nineteenth-century poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, described the sword in full Romantic detail in his poem "Morte d'Arthur", later rewritten as "The Passing of Arthur", one of the Idylls of the King: "There drew he forth the brand Excalibur, / And o’er him, drawing it, the winter moon, / Brightening the skirts of a long cloud, ran forth / And sparkled keen with frost against the hilt / For all the haft twinkled with diamond sparks, / Myriads of topaz-lights, and jacinth-work / Of subtlest jewellery."

References

- Bromwich & Simon Evans 1992, pp. 64–65.

- Green 2007, p. 156.

- Ford 1983, p. 271.

- MacKillop 1998, pp. 64–65, 174.

- Koch, John. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2006, p. 329.

- Hardy, T.D. and Martin, C. T. (eds./trans.), Gaimar, Geoffrey. L'Estoire des Engles (lines 45-46), Eyre and Spottiswoode, London, 1889, p. 2.

- Wright, T. (ed.); Gaimar, Geoffrey. Gaimar, Havelok et Herward, Caxton Society, London, 1850, p. 2

- De Lincy, Roux (ed.), Wace, Roman de Brut, v. II, Edouard Frère, Rouen, 1838, pp. 51, 88, 213, 215.

- Bryant, Nigel (trans., ed.). Perceval: The Story of the Grail, DS Brewer, 2006, p. 69.

- Roach, William. Chrétien De Troyes: Le Roman De Perceval ou Le Conte Du Graal, Librairie Droz, 1959, p. 173.

- Loomis, R. S. Arthurian Tradition and Chrétien de Troyes, Columbia, 1949, p. 424.

- Vinaver, Eugene (ed.) The works of Sir Thomas Malory, Volume 3. Clarendon, 1990, p. 1301.

- Bryant, Nigel (ed, trans), Merlin and the Grail: Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, Perceval : the Trilogy of Prose Romances Attributed to Robert de Boron, DS Brewer, 2001, p. 107ff.

- Sir Thomas Malory, William Caxton "Morte Darthur: Sir Thomas Malory's Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table". p. 28. J.B. Lippincott and Company, 1868.

- Micha, Alexandre (ed.). Merlin: roman du XIIIe siècle (Geneva: Droz, 1979).

- Lacy 1996.

- Malory 1997, p. 7.

- Malory 1997, p. 46.

- Thurneysen, R. "Zur Keltischen Literatur und Grammatik", Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie, Volume 12, p. 281ff.

- O'Rahilly, T. F. Early Irish history and mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1957, p. 68.

- Gantz 1987, p. 184.

- Zimmer, Heinrich. "Bretonische Elemente in der Arthursage des Gottfried von Monmouth", Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur, Volume 12, E. Franck's, 1890, p. 236.

- Jones & Jones 1949, p. 136.

- Alliterative Morte Arthure, TEAMS, retrieved 26-02-2007

- Warren, Michelle. History On The Edge: Excalibur and the Borders of Britain, 1100-1300 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press) p. 212.

- Tri Thlws ar Ddeg, ed. and tr. Bromwich (1978): pp. 240–1.

Sources

- The Works of Sir Thomas Malory, Ed. Vinaver, Eugène, 3rd ed. Field, Rev. P. J. C. (1990). 3 vol. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-812344-2, ISBN 0-19-812345-0, ISBN 0-19-812346-9.

- Bromwich, R.; Simon Evans, D. (1992). Culhwch and Olwen. An Edition and Study of the Oldest Arthurian Tale. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ford, P.K. (1983). "On the Significance of some Arthurian Names in Welsh". Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. 30: 268–73.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gantz, Jeffrey (1987). The Mabinogion. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044322-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Green, T. (2007). Concepts of Arthur. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-4461-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, T.; Jones, G. (1949). The Mabinogion. London: Dent.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lacy, Norris J. (1996). Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation. New York: Garland.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacKillop, James (1998). Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malory, Thomas (1997). Le Morte D'Arthur. University of Michigan Humanities Text Initiative.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Micha, Alexandre (1979). Merlin: roman du XIIIe siècle. Geneva: Droz.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Lacy, N. J (ed). The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. (London: Garland. 1996). ISBN 0-8153-2303-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Excalibur. |