Cædwalla of Wessex

Cædwalla (/ˈkædˌwɔːlə/ KAD-wawl-ə; c. 659 – 20 April 689 AD) was the King of Wessex from approximately 685 until he abdicated in 688. His name is derived from the Welsh Cadwallon. He was exiled from Wessex as a youth and during this period gathered forces and attacked the South Saxons, killing their king, Æthelwealh, in what is now Sussex. Cædwalla was unable to hold the South Saxon territory, however, and was driven out by Æthelwealh's ealdormen. In either 685 or 686, he became King of Wessex. He may have been involved in suppressing rival dynasties at this time, as an early source records that Wessex was ruled by underkings until Cædwalla.

| Cædwalla | |

|---|---|

| King of Wessex | |

.jpg) Imaginary depiction of Cædwalla by Lambert Barnard | |

| King of Wessex | |

| Reign | 685–688 |

| Predecessor | Centwine |

| Successor | Ine |

| Born | c. 659 |

| Died | 20 April 689 (aged 29–30), Rome, Italy |

| Consort | Cynethryth |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Coenberht |

After his accession Cædwalla returned to Sussex and won the territory again, and also conquered the Isle of Wight, engaging in genocide, extinguishing the ruling dynasty there, and forcing the population of the island at sword point to renounce their pagan beliefs for Christianity.[1] He gained control of Surrey and the kingdom of Kent, and in 686 he installed his brother, Mul, as king of Kent. Mul was burned in a Kentish revolt a year later, and Cædwalla returned, possibly ruling Kent directly for a period.

Cædwalla was wounded during the conquest of the Isle of Wight, and perhaps for this reason he abdicated in 688 to travel to Rome for baptism. He reached Rome in April 689, and was baptised by Pope Sergius I on the Saturday before Easter, dying ten days later on 20 April 689. He was succeeded by Ine.

Sources

A major source for West Saxon events is the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written about 731 by Bede, a Northumbrian monk and chronicler. Bede received a good deal of information relating to Cædwalla from Bishop Daniel of Winchester; Bede's interest was primarily in the Christianization of the West Saxons, but in relating the history of the church he sheds much light on the West Saxons and on Cædwalla.[2] The contemporary Vita Sancti Wilfrithi or Life of St Wilfrid (by Stephen of Ripon, but often misattributed to Eddius Stephanus) also mentions Cædwalla.[3] Another useful source is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a set of annals assembled in Wessex in the late 9th-century, probably at the direction of King Alfred the Great. Associated with the Chronicle is a list of kings and their reigns, known as the West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List.[2] There are also six surviving charters, though some are of doubtful authenticity. Charters were documents drawn up to record grants of land by kings to their followers or to the church, and provide some of the earliest documentary sources in England.[4]

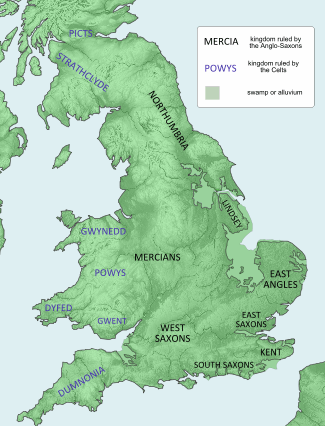

West Saxon territory in the 680s

In the late 7th century, the West Saxons occupied an area in the west of southern England, though the exact boundaries are difficult to define.[5] To their west was the native British kingdom of Dumnonia, in what is now Devon and Cornwall. To the north were the Mercians, whose king, Wulfhere, had dominated southern England during his reign. In 674 he was succeeded by his brother, Æthelred, who was less militarily active than Wulfhere had been along the frontier with Wessex, though the West Saxons did not recover the territorial gains Wulfhere had made.[6] To the southeast was the kingdom of the South Saxons, in what is now Sussex; and to the east were the East Saxons, who controlled London.[7]

Not all the locations named in the Chronicle can be identified, but it is apparent that the West Saxons were fighting in north Somerset, south Gloucestershire, and north Wiltshire, against both British and Mercian opposition. To the west and south, evidence of the extent of West Saxon influence is provided by the fact that Cenwalh, who reigned from 642 to 673, is remembered as the first Saxon patron of Sherborne Abbey, in Dorset; similarly, Centwine (676–685) is the first Saxon patron of Glastonbury Abbey, in Somerset. Evidently these monasteries were in West Saxon territory by then. Exeter, to the west, in Devon, was under West Saxon control by 680, since Boniface was educated there at about that time.[5]

Ancestry

Bede states that Cædwalla was a "daring young man of the royal house of the Gewissæ", and gives his age at his death in 689 as about thirty, making the year of his birth about 659.[8] "Gewisse", a tribal name, is used by Bede as an equivalent to "West Saxon": the West Saxon genealogies trace back to one "Gewis", an invented eponymous ancestor.[9] According to the Chronicle, Cædwalla was the son of Coenberht, and was descended via Ceawlin from Cerdic, who was the first of the Gewisse to land in England.[10][11] However, it appears that the many difficulties and contradictions in the regnal list are caused partly by the efforts of later scribes to demonstrate that each king on the list was descended from Cerdic; thus Cædwalla's genealogy must be treated with caution.[12] His name is an Anglicised form of the British name "Cadwallon", which may indicate British (Brythonic) ancestry.[13]

First campaign in Sussex

The first mention of Cædwalla is in the Life of St Wilfrid, in which he is described as an exiled nobleman in the forests of Chiltern and Andred.[14] It was not uncommon for a 7th-century king to have spent time in exile before gaining the throne; Oswald of Northumbria is another prominent example.[15] According to the Chronicle, it was in 685 that Cædwalla "began to contend for the kingdom".[10] Despite his exile, he was able to put together enough military force to defeat and kill Æthelwealh, the king of Sussex. He was, however, soon expelled by Berthun and Andhun, Æthelwealh's ealdormen, "who administered the country from then on", possibly as kings.[16]

The Isle of Wight and the Meon valley in what is now eastern Hampshire had been placed under Æthelwealh's control by Wulfhere;[17] the Chronicle dates this to 661, but according to Bede it occurred "not long before" Wilfrid's mission to the South Saxons in the 680s, which implies a rather later date. Wulfhere's attack on Ashdown, also dated by the Chronicle to 661, may likewise have actually happened later. If these events happened in the early 680s or not long before, Cædwalla's aggression against Æthelwealh would be explained as a response to Mercian pressure.[6]

Another indication of the political and military situation may be the division in the 660s of the West Saxon see at Dorchester-on-Thames; a new see was established at Winchester, very near to the South Saxon border. Bede's explanation for the division is that Cenwalh grew tired of the Frankish speech of the bishop at Dorchester,[18] but it is more likely that it was a response to the Mercian advance, which forced West Saxon expansion, such as Cædwalla's military activities, west, south, and east, rather than north.[5] Cædwalla's military successes may be the reason that at about this time the term "West Saxon" starts to be used in contemporary sources, instead of "Gewisse". It is from this time that the West Saxons began to rule over other Anglo-Saxon peoples.[5]

Accession and reign

In 685 or 686, Cædwalla became king of the West Saxons after Centwine, his predecessor, retired to a monastery.[5] Bede gives Cædwalla a reign of two years,[19] ending in 688, but if his reign was less than three years then he may have come to the throne in 685. The West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List gives his reign a length of three years, with one variant reading of two years.[17]

According to Bede, before Cædwalla's reign, Wessex was ruled by underkings, who were conquered and removed when Cædwalla became king.[20] This has been taken to mean that Cædwalla himself ended the reign of the underkings, though Bede does not directly say this. Bede gives the death of Cenwalh as the start of the ten-year period in which the West Saxons were ruled by these underkings; Cenwalh is now thought to have died in about 673, so this is slightly inconsistent with Cædwalla's dates. It may be that Centwine, Cædwalla's predecessor as king of the West Saxons, began as a co-ruler but established himself as sole king by the time Cædwalla became king.[21][22] It may also be that the underkings were another dynastic faction of the West Saxon royal line, vying for power with Centwine and Cædwalla; the description of them as "underkings" may be due to a partisan description of the situation by Bishop Daniel of Winchester, who was Bede's primary informant on West Saxon events.[23] It is also possible that not all the underkings were deposed. There is a King Bealdred, who reigned in the area of Somerset and West Wiltshire, who is mentioned in two land-grants, one dated 681 and the other 688, though both documents have been treated as spurious by some historians.[24][25] Further confusing the situation is another land-grant, thought to be genuine,[26] showing Ine's father, Cenred, still reigning in Wessex after Ine's accession.[17]

Once on the throne, Cædwalla attacked the South Saxons again, this time killing Berthun, and "the province was reduced to a worse state of subjection".[16] He also conquered the Isle of Wight, which was still an independent pagan kingdom, and set himself to kill every native on the island, resettling it with his own people. Arwald, the king of the Isle of Wight, left his two young brothers as heirs. They fled the island, but were found at Stoneham, in Hampshire, and killed on Cædwalla's orders, though he was persuaded by a priest to let them be baptised before they were executed. Bede also mentions that Cædwalla was wounded; he was recovering from his wounds when the priest found him to ask permission to baptise the princes.[27]

In a charter of 688, Cædwalla grants land at Farnham for a minster,[28] so it is evident that Cædwalla controlled Surrey. He also invaded Kent, in 686, and may have founded a monastery at Hoo, northeast of Rochester, between the Medway and the Thames. He installed his brother, Mul, as king of Kent, in place of its king Eadric. In a subsequent Kentish revolt, Mul was "burned" along with twelve others, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Cædwalla responded with a renewed campaign against Kent, laying waste to its land and leaving it in a state of chaos. He may have ruled Kent directly after this second invasion.[29]

Christianity

Cædwalla was unbaptised when he came to the throne of Wessex, and remained so throughout his reign, but though he is often referred to as a pagan this is not necessarily the most apt description; it may be that he was already Christian in his beliefs but delayed his baptism to a time of his choice.[30] He was clearly respectful of the church, with charter evidence showing multiple grants to churches and for religious buildings.[4] When Cædwalla first attacked the South Saxons, Wilfrid was at the court of King Æthelwealh, and on Æthelwealh's death Wilfrid attached himself to Cædwalla;[17] the Life of Wilfrid records that Cædwalla sought Wilfrid out as a spiritual father.[14] Bede states that Cædwalla vowed to give a quarter of the Isle of Wight to the church if he conquered the island and that Wilfrid was the beneficiary when the vow was fulfilled; Bede also says that Cædwalla agreed to let the heirs of Arwald, the king of the Isle of Wight, be baptised before they were executed.[27] Two of Cædwalla's charters were grants of land to Wilfrid,[4] and there is also subsequent evidence that Cædwalla worked with Wilfrid and Eorcenwald, a bishop of the East Saxons, to establish an ecclesiastical infrastructure for Sussex.[31] However, there is no evidence that Wilfrid exerted any influence over Cædwalla's secular activities or his campaigns.[32]

Wilfrid's association with Cædwalla may have benefited him in other ways: the Life of Wilfrid asserts that the Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore, expressed a wish that Wilfrid succeed him in that role, and if this is true it may be a reflection of Wilfrid's association with Cædwalla's southern overlordship.[29]

Abdication, baptism and death

In 688 Cædwalla abdicated and went on a pilgrimage to Rome, possibly because he was dying of the wounds he had suffered while fighting on the Isle of Wight.[5] Cædwalla had not been baptised, and Bede states that he wished to "obtain the particular privilege of receiving the cleansing of baptism at the shrine of the blessed Apostles". He stopped in Francia at Samer, near Calais, where he gave money for the foundation of a church, and is also recorded at the court of Cunincpert, king of the Lombards, in what is now northern Italy.[33] In Rome, he was baptised by Pope Sergius I on the Saturday before Easter (according to Bede) taking the baptismal name Peter, and died not long afterwards, "still in his white garments". He was buried in St. Peter's church. Bede's Ecclesiastical History and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle agree that Cædwalla died on 20 April, but the latter says that he died seven days after his baptism, although the Saturday before Easter was on 10 April that year. The epitaph on his tomb described him as "King of the Saxons".[8][34]

Cædwalla's departure in 688 appears to have led to instability in the south of England. Ine, Cædwalla's successor, abdicated in 726, and the West Saxon Genealogical Regnal List says that he reigned for thirty-seven years, implying his reign began in 689 instead of 688. This could indicate an unsettled period between Cædwalla's abdication and Ine's accession. The kingship also changed in Kent in 688, with Oswine, who was apparently a Mercian client, taking the throne; and there is evidence of East Saxon influence in Kent in the years immediately following Cædwalla's abdication.[35]

In 694, Ine extracted compensation of 30,000 pence from the Kentishmen for the death of Mul; this amount represented the value of an aetheling's life in the Saxon system of Weregild. Ine appears to have retained control of Surrey, but did not recover Kent.[36] No king of Wessex was to venture so far east until Egbert, over a hundred years later.[37]

See also

- House of Wessex family tree

Notes

- Bloxham 2010, pp. 267–268.

- Yorke 1990, pp. 128–130.

- "Stephen of Ripon" in Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net". Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- For a discussion of 7th-century West Saxon expansion, see Yorke 1990, pp. 135–138.

- Kirby 1992, pp. 115–116.

- The general topography of the 7th-century kingdoms is given in map form in Hunter Blair 1966, p. 209.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book V, Ch. 7, from Sherley-Price's translation, p. 275.

- Kirby 1992, pp. 48, 223.

- Swanton 1996, p. 38.

- Yorke 1990, p. 133.

- Yorke 1990, pp. 130–131.

- Yorke 1990, pp. 138–139.

- Kirby 1992, p. 119.

- Campbell, John & Wormald 1991, p. 56.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book IV, Ch. 15, from Sherley-Price's translation, p. 230.

- Kirby 1992, p. 120.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book III, Ch. 7, from Sherley-Price's translation, pp. 153–155.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book V, Ch. 7, from Sherley-Price's translation, pp. 275–276.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book IV, Ch. 12, from Sherley-Price's translation, p. 224.

- Yorke 1990, pp. 145–146.

- Kirby 1992, pp. 51–52.

- Kirby 1992, p. 53.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net S 236". Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net S 1170". Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net S 45". Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book IV, Ch. 16, from Sherley-Price's translation, pp. 230–232.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net S 235". Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- Kirby 1992, p. 121.

- This suggestion is made in Stenton 1971, p. 70 note. For an example of a modern historian referring to Cædwalla unequivocally as a pagan, see Kirby 1992, p. 118.

- Yorke 1990, p. 56.

- Kirby 1992, p. 117.

- Stenton 1971, pp. 2–7.

- Swanton 1996, pp. 40–41.

- Kirby 1992, p. 122.

- Kirby 1992, p. 124.

- Kirby 1992, p. 192.

References

Primary sources

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price, revised R. E. Latham, ed. D.H. Farmer. London: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-044565-X

- Swanton, Michael (1996), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-92129-5

Secondary sources

- Bloxham, Donald (2010), The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-923211-3

- Campbell, James; John, Eric & Wormald, Patrick (1991), The Anglo-Saxons, London: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-014395-5

- Hunter Blair, Peter (1966), Roman Britain and Early England: 55 B.C. – A.D. 871, New York: Norton, ISBN 0-393-00361-2

- Kirby, D. P. (1992), The Earliest English Kings, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-09086-5

- Lapidge, Michael (1999), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-22492-0

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971), Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-821716-1

- Yorke, Barbara (1990), Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, London: Seaby, ISBN 1-85264-027-8