Bwindi Impenetrable National Park

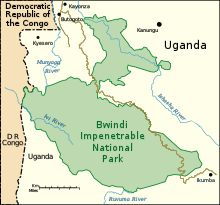

The Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (BINP) is in southwestern Uganda. The park is part of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest and is situated along the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) border next to the Virunga National Park and on the edge of the Albertine Rift. Composed of 321 square kilometres (124 sq mi) of both montane and lowland forest, it is accessible only on foot. BINP is a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization-designated World Heritage Site.[1][2]

| Bwindi Impenetrable National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

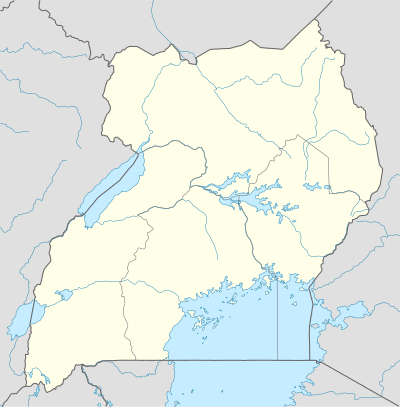

Location of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park | |

| Location | Kanungu District, Uganda |

| Nearest city | Kanungu |

| Coordinates | 01°01′S 29°41′E |

| Area | 331 km2 (128 sq mi) |

| Established | 1991 |

| Governing body | Uganda Wildlife Authority |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, x |

| Designated | 1994 (18th session) |

| Reference no. | 682 |

| State Party | Uganda |

| Region | Africa |

Species diversity is a feature of the park.[3] It provides habitat for 120 species of mammals, 348 species of birds, 220 species of butterflies, 27 species of frogs, chameleons, geckos, and many endangered species. Floristically, the park is among the most diverse forests in East Africa, with more than 1,000 flowering plant species, including 163 species of trees and 104 species of ferns. The northern (low elevation) sector has many species of Guineo-Congolian flora, including two endangered species, the brown mahogany and Brazzeia longipedicellata. In particular, the area shares in the high levels of endemisms of the Albertine Rift.

The park is a sanctuary for colobus monkeys, chimpanzees, and many birds such as hornbills and turacos. It is most notable for the 400 Bwindi gorillas, half of the world's population of the endangered mountain gorillas. 14 habituated mountain gorilla groups are open to tourism in four different sectors of Buhoma, Ruhijja, Rushaga and the Nkuringo in the Districts of Kanungu, Kabale and Kisoro respectively all under the management of Uganda Wildlife Authority.

History

In 1932, two blocks of the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest were designated as Crown Forest Reserves. The northern block was designated as the "Kayonza Crown Forest Reserve", and the southern block designated as the "Kasatora Crown Forest Reserve".[3][4]:7 These reserves had a combined area of 207 square kilometres (80 sq mi). In 1942, the two reserves were combined and enlarged,[3] then renamed the Impenetrable Central Crown Forest.[4]:7 This new protected area covered 298 square kilometres (115 sq mi)[3] and was under the joint control of the Ugandan government's game and forest departments.[4]:7

In 1964, the reserve was designated as an animal sanctuary[5]:43 to provide extra protection for its mountain gorillas[3] and renamed the Impenetrable Central Forest Reserve.[5]:43 In 1966, two other forest reserves became part of the main reserve, increasing its area to almost 321 square kilometres (124 sq mi).[3] The park continued to be managed as both a game sanctuary and forest reserve.[5]:43

In 1991, the Impenetrable Central Forest Reserve, along with the Mgahinga Gorilla Reserve and the Rwenzori Mountains Reserve, was designated as a national park and renamed the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park.[3][6]:233 It covered an area of 330.8 square kilometres (127.7 sq mi).[5]:43 The national park was declared in part to protect a range of species within it, most notably the mountain gorilla.[7] The reclassification of the park had a large impact on the Batwa pygmy people, who were evicted from the forest and no longer permitted to enter the park or access its resources.[4]:8 Gorilla tracking became a tourist activity in April 1993, and the park became a popular tourist destination.[3] In 1994, a 10-square-kilometre (3.9 sq mi) area was incorporated into the park and it was inscribed on the World Heritage List.[3] The park's management changed: Uganda National Parks, since renamed the Uganda Wildlife Authority, became responsible for the park.[4]:7–8 In 2003 a piece of land next to the park with an area of 4.2 square kilometres (1.6 sq mi) was purchased and incorporated into the park.[8]

In March 1999, a force of 100–150 former Rwandan Interahamwe guerrillas infiltrated across the border from the DRC and kidnapped 14 foreign tourists and their Ugandan guide from the park headquarters, eventually releasing six and murdering the remaining eight with machetes and clubs. Several victims were reportedly tortured, and at least one of the female victims was raped. The Ugandan guide was doused with gasoline and lit on fire.[9] The Interahamwe attack was reportedly intended to "destabilize Uganda" and frighten away tourist traffic from the park, depriving the Ugandan government of income. The park was forced to close for several months, and the popularity of the gorilla tours suffered badly for several years, though attendance has since recovered due to greater stability in the area. An armed guard also now accompanies every tour group.[10]

Geography and climate

Kabale town to the south-east is the nearest main town to the park, 29 kilometres (18 mi) away by road.[3] The park is composed of two blocks of forest that are connected by a corridor of forest. The shape of the park is a legacy of previous conservation management, when the original two forest blocks were protected in 1932.[4]:7 There is agricultural land where there were previously trees directly outside the park's borders.[4]:8 Cultivation in this area is intense.[11]

The park's underlying geology consists of Precambrian shale phyllite, quartz, quartzite, schist, and granite. The park is at the edge of the Western Rift Valley in the highest parts of the Kigezi Highlands,[5]:43 which were created by up-warping of the Western Rift Valley.[12] Its topography is very rugged, with narrow valleys intersected by rivers and steep hills. Elevations in the park range from 1,190 to 2,607 metres (3,904 to 8,553 ft) above sea level,[13] and 60 percent of the park has an elevation of over 2,000 metres (6,600 ft). The highest elevation is Rwamunyonyi Hill at the eastern edge of the park. The lowest part of the park is at its most northern tip.[3]

The forest is an important water catchment area. With a generally impermeable underlying geology where water mostly flows through large fault structures, water infiltration and aquifers are limited. Much of the park's rainfall forms streams, and the forest has a dense network of streams. The forest is the source of many rivers that flow to the north, west, and south. Major rivers that rise in the park include the Ivi, Munyaga, Ihihizo, Ishasha, and Ntengyere rivers, which flow into Lake Edward.[12] Other rivers flow into Lakes Mutanda and Bunyonyi.[4]:8 Bwindi supplies water to local agricultural areas.[3]

Bwindi has a tropical climate.[3] Annual mean temperature ranges from a minimum of 7 to 15 °C (45 to 59 °F) to a maximum of 20 to 27 °C (68 to 81 °F). Its annual rainfall ranges from 1,400 to 1,900 millimetres (55 to 75 in). Peak rainfall occurs from March to April and from September to November.[13] The park's forest plays an important role in regulating the surrounding area's environment and climate.[6]:233[11] High amounts of evapotranspiration from the forest's vegetation increases the precipitation that the region outside the park receives. They also lessen soil erosion, which is a serious problem in south-western Uganda. They lessen flooding and ensure that streams continue to flow in the dry season.[11]

Biodiversity

The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is old, complex, and biologically rich.[6]:233 Diverse species are a feature of the park,[3] and it became an UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its ecological importance. Among East African forests, Bwindi has some of the richest populations of trees, small mammals, birds, reptiles, butterflies, and moths. The park's diverse species are partly a result of the large variations of elevation[4]:8 and habitat types in the park,[11] and may also be because the forest was a refuge for species during glaciations in the Pleistocene epoch.[4]:8[11]

The park's forests are afromontane, which is a rare vegetation type on the African continent.[4]:8 Located where plain and mountain forests meet,[3] there is a continuum of low-altitude to high altitude primary forests in the park,[6]:234[14] one of the few large tracts of East African forest where this occurs.[3] The park has more than 220 tree species, and more than 50% of Uganda's tree species,[13] and more than 100 fern species.[3] The brown mahogany is a threatened plant species in the park.[15]

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park is important for the conservation of the afromontane fauna, especially species endemic to the Western Rift Valley's mountains.[15] It is thought to have one of the richest faunal communities in East Africa, including more than 350 bird species and more than 200 butterfly species.[3] There are an estimated 120 mammal species in the park, of which 10 are primates,[16]:744 and more than 45 are small mammals.[13] Along with mountain gorilla, species in the park include common chimpanzee, L'Hoest's monkey, African elephant, African green broadbill, and cream-banded swallowtail,[15] black and white colobus, red-tailed monkeys, vervets,[16]:744 the giant forest hog,[13] and small antelope species.[17] The fish species in the park's rivers and streams are not well known.[12] There are also many carnivores, including the side-striped jackal, African golden cat, and African civet.

Mountain gorillas

The park is inhabited by about 600 individual mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei),[18] known as the Bwindi population, which makes up almost half of all the mountain gorillas in the world.[6]:234 The rest of the worldwide mountain gorilla population lives in the nearby Virunga Mountains. A 2006 census of the mountain gorilla population in the park showed that its numbers had increased modestly from an estimated 300 individuals in 1997,[19] to 320 individuals in 2002 to 340 individuals in 2006,[18] and 400 in 2018.[20] Poaching, disease and habitat loss are the greatest threat to the gorillas.[21]

Research on the Bwindi population lags behind that of the Virunga National Park population, but some preliminary research on the Bwindi gorilla population has been carried out by Craig Stanford. This research has shown that the Bwindi gorilla's diet is markedly higher in fruit than that of the Virunga population, and that the Bwindi gorillas, even silverbacks, are more likely to climb trees to feed on foliage, fruits, and epiphytes. In some months, the Bwindi gorilla diet is very similar to that of Bwindi chimpanzees. It was also found that Bwindi gorillas travel farther per day than Virunga gorillas, particularly on days when feeding primarily on fruit than when they are feeding on fibrous foods. Additionally, Bwindi gorillas are much more likely to build their nests in trees, nearly always in Alchornea floribunda (locally, "Echizogwa"), a small understory tree.

The mountain gorilla is an endangered species, with an estimated total population of about 650 individuals.[5] There are no mountain gorillas in captivity, but during the 1960s and 1970s, some were captured to start captive breeding.[21]

Conservation

The park is owned by the Uganda Wildlife Authority, a parastatal government body. The park has total protection, although communities adjacent to the park can access some of its resources.[3]

The areas bordering the park have a high population density of more than 300 people per square kilometer. Some of the people who live in these areas are among the poorest people in Uganda. The high population and poor agricultural practises place a great pressure on the Bwindi forest, and are one of the biggest threats to the park.[4]:3 Ninety percent of the people are dependent on subsistence agriculture, as agriculture is one of the area's few ways of earning income.[4]:5

Prior to Bwindi's gazetting as a national park in 1991, the park was designated as a forest reserve, and regulations about the right to access the forest were more liberal and seldom enforced.[6]:233 Local people hunted, mined, logged, pit sawed, and kept bees in the park.[5]:44 It was gazetted as a national park in 1991 because of its rich biodiversity and threats to the integrity of the forest. Its designation as a national park gave the park higher protection status.[6]:233 State agencies increased protection and control of the park.[5]:44 Adjacent communities' access to the forest immediately ended. This closing of access caused large amounts of resentment and conflict among these local communities[6]:233 and park authorities.[5]:45 The Batwa, a group that had relied on the forest, were badly affected.[5]:44 The Batwa fished, harvested wild yams and honey, and had ancestral sites within the park.[5]:60 Despite the Batwa people's historical claim to land rights and having lived in the area for generations without destroying the area's ecosystem, they did not benefit from any national compensation scheme when they were evicted. Non-Batwa farmers who had cut down the forested areas in order to cultivate them, received compensation and their land rights were recognised.[22] People have lost livestock and crops from wildlife, and there have been some human deaths.[5]:45 The habituation of gorillas to humans in order to facilitate tourism may have increased the damage they do to local people's property because their fear of people has decreased.[5]:53

Tourism

Tourists may visit the park any time during the year, although conditions in the park are more difficult during the rainy season. The park is in a remote location, and the roads are in poor condition.[4]:8 Tourist accommodations include a lodge, tented camps, and rooms run by the community located near the Buhoma entrance gate.[23]

Bwindi Community Hospital provides health care to 40,000 people in the area and to visiting tourists.[24]

Gorilla tracking is the park's main tourist attraction, and it generates much revenue for Uganda Wildlife Authority.[6]:234 Tourists wishing to track gorillas must first obtain a permit.[23] Selected gorillas families have been habituated to human presence, and the number of visitors is tightly controlled to prevent risks to the gorillas and degradation of the habitat. Several tour companies are able to reserve gorilla tracking permits for prospective visitors to Bwindi. The gorillas seldom react to tourists. There are strict rules for tourists to minimize the risk of disease transmission to the gorillas.[21] Uganda, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are the only countries where it is possible to visit mountain gorillas.[16]:743 Guided walks through the forest include a walk to a waterfall, and walks for monkey watching and birding.[23]

See also

- Institute of Tropical Forest Conservation — a forest research institute in the park.

- Forests of Uganda

- Tropical rainforests ecoregions

References

- Bwindi Impenetrable National Park profile on UNESCO's World Heritage website

- Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, UNESCO World Heritage Site listing

- "Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda". Protected Areas and World Heritage. United Nations Environment Programme, World Conservation Monitoring Centre. September 2003. Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Korbee, Dorien (March 2007). "Environmental Security in Bwindi: A focus on farmers" (PDF). Institute for Environmental Security. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Namara, Agrippinah (June 2006). "From Paternalism to Real Partnership with Local Communities? Experiences from Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (Uganda)". Africa Development. XXXI (2).

- Blomley, Tom (2003). "Natural resource conflict management: the case of Bwindi Impenetrable and Mgahinga Gorilla National Parks, southwestern Uganda" (PDF). In Peter A. Castro, Erik Nielsen (ed.). Natural resource conflict management case studies: an analysis of power, participation and protected areas. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Adams, William Mark (2001). Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in the Third World. Routledge. p. 266. ISBN 0-415-14765-4.

- "A brief history of IGCP". International Gorilla Conservation Programme. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- "Uganda tourists 'butchered'". BBC. 3 March 1999. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- "Court finds Rwandan guilty of murdering tourists 7 years ago". IRIN. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 2006-01-09. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- Lanjouw, Annette (2001). "Beyond Boundaries: Transboundary Natural Resource Management for Mountain Gorillas in the Virunga-Bwindi Region". Biodiversity Support Program, World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Gurrieri, Joe; Jason Gritzner; Mike Chaveas. "Virunga – Bwindi Region: Republic of Rwanda, Republic of Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-07-04. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Eilu, Gerald; Joseph Obua (2005). "Tree condition and natural regeneration in disturbed sites of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park, southwestern Uganda". Tropical Ecology. 46 (1): 99–111.

- Gurrieri, J.; Chaveas, M.; Gritzner, J. (2005). Virunga – Bwindi Region: Republic of Rwanda, Republic of Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo. USDA Forest Service. p. 9.

- IUCN/WCMC (1994). World Heritage Nomination - IUCN Summary Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (Uganda) (PDF). p. 51.

- Hodd, M. (2002). East Africa Handbook: The Travel Guide. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 1-900949-65-2.

- "Bwindi Impenetrable National Park". National Parks and Safaris. Uganda Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 2008-06-05. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- "Mountain Gorilla Population Rebounds in Uganda". LiveScience.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- http://www.igcp.org/wp-content/themes/igcp/docs/pdf/Bwindicensus2006resultssummary.pdf

- Robbins, M.; Sawyer, S. (2007). "Intergroup encounters in mountain gorillas of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda". Behaviour. 144 (12): 1497–1519. doi:10.1163/156853907782512146. ISSN 0005-7959.

- "About IGCP". International Gorilla Conservation Programme. Archived from the original on 2008-01-17. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- AFRICA: Land rights and pygmy survival Archived 2009-06-28 at the Wayback Machine, IRIN Africa, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

- "Bwindi Impenetrable National Park". Uganda Wildlife Authority. Archived from the original on 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Bwindi Community Hospital website Archived 2008-02-02 at the Wayback Machine

External links

![]()

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. |

- Updated Guide to Bwindi Impenetrable Forest National Park

- "Bwindi Impenetrable National Park guide". Uganda Wildlife Authority.

- BirdLife International. "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Bwindi Impenetrable National Park".

- "Bwindi Mgahinga Conservation Trust". Archived from the original on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2019-04-11.

- Bwindi Impenetrable Indepth Guide

- ESA.int: Map of Bwindi Impenetrable Forest