Semuliki National Park

Semuliki National Park, is located in Bwamba County, a remote part of the Bundibugyo District, in the Western Region of Uganda. It was made a national park in October 1993 and is one of Uganda's newest national parks.[1] 219 km2 (85 sq mi) of East Africa's only lowland tropical rainforest is found in the park.[2] It is one of the richest areas of floral and faunal diversity in Africa, with bird and butterfly species being especially diverse. The park is managed by the Uganda Wildlife Authority.[1]

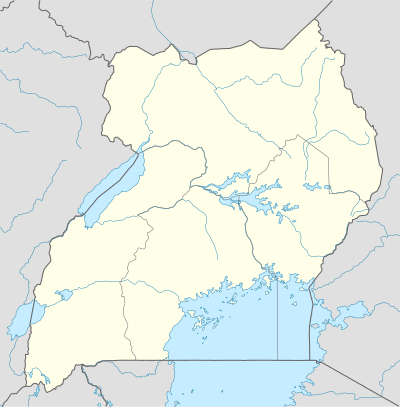

| Semuliki National Park | |

|---|---|

Location of Semuliki National Park | |

| Location | Bundibugyo District, Uganda |

| Nearest city | Fort Portal |

| Coordinates | 00°49′30″N 30°03′40″E |

| Area | 220 km2 (85 sq mi) |

| Established | October 1993 |

| Governing body | Uganda Wildlife Authority |

Location

Semuliki National Park lies on Uganda's border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Rwenzori Mountains are to the south-east of the park, while Lake Albert is to the park's north.[1] The park lies within the Albertine Rift, the western arm of the East African Rift.[3] The park is located on a flat to gently undulating landform that ranges from 670 to 760 m (2,200 to 2,490 ft) above sea level.[1]

The park experiences an average rainfall of 1,250 mm (49 in), with peaks in rainfall from March to May and from September to December. Many areas of the park experience flooding during the wet season. The temperature at the park varies from 18 to 30 °C (64 to 86 °F), with relatively small daily variations.[1]

The park borders the Semliki and Lamia Rivers,[3] which are watering places for many animals.[4] The park has two hot springs in a hot mineral encrusted swamp.[1] One of the springs - Mumbuga spring - resembles a geyser by forming a 0.5 m high fountain. These hot springs attract a large number of shorebirds and provide salt licks for many animals.[4]

From 1932 to 1993, the area covered by Semuliki National Park was managed as a forest reserve, initially by the colonial government and then by the Ugandan government's Forest Department. It was made a national park by the government in October 1993 to protect the forests as an integral part of the protected areas of the Western Rift Valley.[3]

The park is part of a network of protected areas in the Albertine Rift Valley. Other protected areas in this network include:

- Rwenzori Mountains - In Uganda

- Bwindi Impenetrable National Park - In Uganda

- Kibale National Park - In Uganda

- Queen Elizabeth National Park - In Uganda

- Virunga National Park - In the DR Congo

- Volcanoes National Park - In Rwanda

Park visitors can engage in birdwatching, walking to the savannah grassland, hiking through the 13 km (8.1 mi) Kirumia Trail, and visit the hot springs where the water is hot enough to cook eggs and plantain.[5]

Flora and fauna

The area of Semuliki National Park is a distinct ecosystem within the larger Albertine Rift ecosystem. The park is located at the junction of several climatic and ecological zones, and as a result has a high diversity of plant and animal species and many microhabitats. Most of the plant and animal species in the park are also found in the Congo basin forests, with many of these species reaching the eastern limit of their range in Semuliki National Park. The vegetation of the park is predominantly medium altitude moist evergreen to semi deciduous forest. The dominant plant species in the forest is the Uganda ironwood (Cynometra alexandri). There are also tree species of a more evergreen nature and swamp forest communities.[3]

The park has more than 400 bird species, including the lyre-tailed honey guide.[2] 216 of these species (66 percent of the country's total bird species) are true forest birds, including the rare Oberländer's ground thrush (Geokichla oberlaenderi), Sassi's olive greenbul (Phyllastrephus lorenzi) and nine hornbill species.[3] The park provides habitat for over 60 mammal species, including African buffalo, leopard, hippopotamus, mona monkey, water chevrotain,[2] bush babies, African civet, African elephant,[4] and the Pygmy scaly-tailed flying squirrel (Idiurus zenkeri). Nine duiker species are found in the park, including the bay duiker (Cephalophus dorsalis).[3] The park has eight primate species and almost 460 butterfly species.[6]

Human population

The forests in the park are of great socio-economic importance to the human communities that live near the park. The local people practise subsistence agriculture and use the park's forests to supplement their livelihoods. Some of the products they obtain from the forests include fruits and vegetables, herbal medicines, and construction materials. The local population is increasing at a rate of 3.4 percent per year. The high population density and declining agricultural productivity combined with an unavailability of alternative sources of income means that the local population is dependent on the park's resources. The forest also plays an important cultural and spiritual role in local people's lives. The forests are also the home of approximately 100 Basua people, an indigenous community who still largely live as hunter-gatherers.[7] Because tourism provides the Basua people with an additional source of income, park visitors can learn more about the Basua people's culture and history at the park and see handmade crafts that they have produced.[8]

Past practises of the managing authorities that excluded the local people created resentment among them. This reduced the effectiveness of conservation practices and contributed to the occurrence of illegal activities. Since the 1990s, the Ugandan Wildlife Authority has involved the local communities in park planning.[3]

Civil unrest took place in the Bundibugyo District between 1997 and 2001. On 16 June 1997, Allied Democratic Forces rebels attacked and took over the town of Bundibugyo and occupied the park headquarters. The people who lived near the park were moved to internally displaced people's camps.[3]

See also

References

- Uganda Wildlife Authority (2006). "Semliki National Park". Entebbe: Uganda Wildlife Authority. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Riley, Laura; William Riley (3 January 2005). Nature's Strongholds. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12219-9.

- Florence Chege (July–August 2002). "Kibale and Semuliki Conservation and Development Project" (PDF). IUCN. Retrieved 18 January 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - National Commissions for UNESCO Annual Reports. "Uganda, the pearl of Africa". Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- "Semuliki National Park - Activities". www.ugandawildlife.org. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- Forbes, S. (2018). The butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidia) of Semuliki National Park, western Uganda. Metamorphosis 29: 29–41.

- http://www.survivalinternational.org/material/20

- "Cultural Encounters in Semuliki". www.ugandawildlife.org. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Semuliki National Park. |