Bury St Edmunds

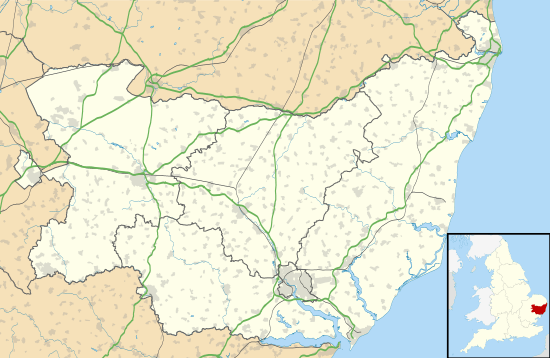

Bury St Edmunds (/ˈbɛri/), commonly referred to locally as Bury, is a historic market town and civil parish in Suffolk, England.[2] Bury St Edmunds Abbey is near the town centre. Bury is the seat of the Diocese of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich of the Church of England, with the episcopal see at St Edmundsbury Cathedral.

| Bury St Edmunds | |

|---|---|

.jpg) St Edmundsbury Cathedral | |

Bury St Edmunds Location within Suffolk | |

| Population | 40,664 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TL855645 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BURY ST. EDMUNDS |

| Postcode district | IP32, IP33 |

| Dialling code | 01284 |

| Police | Suffolk |

| Fire | Suffolk |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

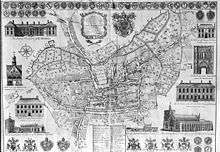

The town, originally called Beodericsworth,[3] was built on a grid pattern by Abbot Baldwin around 1080.[4] It is known for brewing and malting (Greene King brewery)[5] and for a British Sugar processing factory, where Silver Spoon sugar is produced. The town is the cultural and retail centre for West Suffolk and tourism is a major part of the economy.

Etymology

The name Bury is etymologically connected with borough,[6] which has cognates in other Germanic languages such as the German burg meaning "fortress, castle"; Old Norse borg meaning "wall, castle"; and Gothic baurgs meaning "city".[7] They all derive from Proto-Germanic *burgs meaning "fortress". This in turn derives from the Proto-Indo-European root *bhrgh meaning "fortified elevation", with cognates including Welsh bera ("stack") and Sanskrit bhrant- ("high, elevated building").

The second section of the name refers to Edmund King of the East Angles, called Edmund the Martyr, who was killed by the Vikings in the year 869. He became venerated as a saint and a martyr, and his shrine made Bury St Edmunds an important place of pilgrimage.

The formal name of the diocese is "St Edmundsbury", and the town is colloquially known as Bury.

History

An archaeological study in the 2010s on the outskirts of Bury St Edmunds (Beodericsworth, Bedrichesworth, St Edmund's Bury) uncovered evidence of Bronze Age activity in the area. The dig also uncovered Roman coins from the first and second centuries.[8] Samuel Lewis, writing in 1848, notes the earlier discovery of Roman antiquities, and as with several other writers connects Bury St Edmunds with Villa Faustini or Villa Faustina, although the location of this Roman site is also discussed by E. Gillingwater (1804) who notes the lack of evidence for it being here.[9][10][11]

The town was one of the royal boroughs of the Saxons.[9] Sigebert, king of the East Angles, founded a monastery here about 633, which in 903 became the burial place of King Edmund the Martyr, who was slain by the Danes in 869, and owed most of its early celebrity to the reputed miracles performed at the shrine of the martyr king. The town grew around Bury St Edmunds Abbey, a site of pilgrimage. By 925 the fame of St Edmund had spread far and wide, and the name of the town was changed to St Edmund's Bury.

In 942 or 945, King Edmund I had granted to the abbot and convent jurisdiction over the whole town, free from all secular services, and Canute in 1020 freed it from episcopal control. Edward the Confessor made the abbot lord of the franchise. Sweyn, in 1020, having destroyed the older monastery and ejected the secular priests, built a Benedictine abbey on St Edmund's Bury.[12] Count Alan Rufus is said to have been interred at Bury St Edmunds Abbey in 1093. In the 12th and 13th centuries the head of the de Hastings family, who held the Lordship of the Manor of Ashill in Norfolk, was hereditary Steward of this abbey.[13]

On 18 March 1190, two days after the more well-known massacre of Jews at Clifford Tower in York, the people of Bury St Edmunds massacred 57 Jews.[14][15] Later that year, Abbot Samson successfully petitioned King Richard I for permission to evict the town's remaining Jewish inhabitants "on the grounds that everything in the town... belonged by right to St Edmund: therefore, either the Jews should be St Edmund’s men or they should be banished from the town."[16] This expulsion predates the Edict of Expulsion by 100 years. In 1198, a fire burned the shrine of St Edmund, leading to the inspection of his corpse by Abbot Samson and the translation of St Edmund's body to a new location in the abbey.[16]

The town is associated with Magna Carta. In 1214 the barons of England are believed to have met in the Abbey Church and sworn to force King John to accept the Charter of Liberties, the document which influenced the creation of the Magna Carta,[12] a copy of which was displayed in the town's cathedral during the 2014 celebrations. By various grants from the abbots, the town gradually attained the rank of a borough.

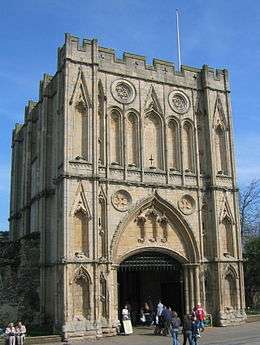

Henry III in 1235 granted to the abbot two annual fairs, one in December (which still survives) and the other the great St Matthew's fair, which was abolished by the Fairs Act of 1871.[12] In 1327, the Great Riot occurred, in which the local populace led an armed revolt against the Abbey.[17] The burghers were angry at the overwhelming power, wealth and corruption of the monastery, which ran almost every aspect of local life with a view to enriching itself. The riot destroyed the main gate and a new, fortified gate was built in its stead.[17] However, in 1381 during the Great Uprising, the Abbey was sacked and looted again. This time, the Prior was executed; his severed head was placed on a pike in the Great Market. On 11 April 1608 a great fire broke out in Eastgate Street, which resulted in 160 dwellings and 400 outhouses being destroyed.[17]

The town developed into a flourishing cloth-making town, with a large woollen trade, by the 14th century.[17] In 1405 Henry IV granted another fair.[12]

Elizabeth I in 1562 confirmed the charters which former kings had granted to the abbots. The reversion of the fairs and two markets on Wednesday and Saturday were granted by James I in fee farm to the corporation. James I in 1606 granted a charter of incorporation with an annual fair in Easter week and a market. James granted further charters in 1608 and 1614, as did Charles II in 1668 and 1684.[12]

Parliaments were held in the borough in 1272, 1296 and 1446, but the borough was not represented until 1608, when James I conferred on it the privilege of sending two members.[12] The Redistribution of Seats Act 1885 reduced the representation to one.[12]

The borough of Bury St Edmunds and the surrounding area, like much of East Anglia, being part of the Eastern Association, supported Puritan sentiment during the first half of the 17th century. By 1640, several families had departed for the Massachusetts Bay Colony as part of the wave of emigration that occurred during the Great Migration.[18] Bury's ancient grammar school also educated such notables as the puritan theologian Richard Sibbes, master of St Catherine's Hall in Cambridge, antiquary and politician Simonds d'Ewes, and John Winthrop the Younger,[19] who became governor of Connecticut.

The town was the setting for witch trials between 1599 and 1694.[20]

Modern history

The population had reached 12,538 by 1841.[21]

A permanent military presence was established in the town with the completion of the Militia Barracks in 1857[22] and of Gibraltar Barracks in 1878.[23]

During the Second World War, the USAAF used Rougham Airfield outside the town.[24]

On 3 March 1974 a Turkish Airlines DC10 jet Flight 981 crashed near Paris killing all 346 people on board. Among the victims were 17 members of Bury St Edmunds Rugby Football Club, returning from France.[25]

The town council was formed in 2003.[26] The election on 3 May 2007 was won by the "Abolish Bury Town Council" party.[27] The party lost its majority following a by-election in June 2007 and, to date, the Town Council is still in existence.[28] In March 2008 a further by-election put Conservatives in control but in the council election of May 2011 the lack of Conservative and other parties' candidates let in a Labour majority before the election was even held.[29] By 2013 a number of by-elections put Conservatives in control again[30] and in the 2015 election Conservatives won 14 of the 17 vacancies.[31]

Notable features

Near the Abbey Gardens stands Britain's first internally illuminated street sign, the Pillar of Salt which was built in 1935. The sign is at the terminus of the A1101, Great Britain's lowest road.

There is a network of tunnels which are evidence of chalk-workings,[32] though there is no evidence of extensive tunnels under the town centre. Some buildings have inter-communicating cellars. Due to their unsafe nature the chalk-workings are not open to the public, although viewing has been granted to individuals. Some have caused subsidence within living memory, for instance at Jacqueline Close.[33]

Among noteworthy buildings is St Mary's Church, where Mary Tudor, Queen of France and sister of Tudor king Henry VIII, was re-buried, six years after her death, having been moved from the Abbey after her brother's Dissolution of the Monasteries. Queen Victoria had a stained glass window fitted into the church to commemorate Mary's interment.[34] Moreton Hall, a Grade II*listed building by Robert Adam, now houses the Moreton Hall Preparatory School.[35] Bury St Edmunds Guildhall dates back to the late 12th century.[36]

Bury St Edmunds has one of the full-time fire stations run by Suffolk Fire and Rescue Service. Originally located in the Traverse (now the Halifax bank),[37] it moved to Fornham Road in 1953. The Fornham Road site (now Mermaid Close) closed in 1987 and the fire station moved to its current location on Parkway North.[38]

Since March 2015, Bury St Edmunds has been the home town of the London and South East Regional Divorce Unit and the Maintenance Enforcement Business Centre (for issues with maintenance payments outside Greater London). The former processes divorce documents from across London and South East England as one of five centralised units covering the United Kingdom. Both units are based with Bury St Edmunds County Court in Triton House, St Andrews Street North.

Geography

Bury is located in the middle of an undulating area of East Anglia known as the East Anglian Heights, with land to the east and west of the town rising to above 100 metres (328 feet), though parts of the town itself are as low as 30 metres (98 feet) above sea level where the Rivers Lark and Linnet pass through it.

Climate

There are two Met Office reporting stations in the vicinity of Bury St Edmunds, Brooms Barn (elevation 76m), 6.5 miles to the west of the town centre, and Honington (elevation 51m), about 6.5 miles to the north. According to Usman Majeed, head of Honington, it ceased weather observations in 2003, though Brooms Barn remains operational. Brooms Barn's record maximum temperature stands at 36.7C (98.1F), recorded in August 2003.[39] The lowest recent temperature was −10.0C (14.0f)[40] during December 2010.

Rainfall is generally low, at under 600mm, and spread fairly evenly throughout the year.

| Climate data for Honington, elevation 51m, 1971–2000. Rainfall data 1981–1990 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

0.9 (33.6) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53.7 (2.11) |

30.1 (1.19) |

49.9 (1.96) |

47.6 (1.87) |

46.2 (1.82) |

54.7 (2.15) |

43.4 (1.71) |

49.1 (1.93) |

41.2 (1.62) |

65.6 (2.58) |

47.2 (1.86) |

49.6 (1.95) |

578.3 (22.77) |

| Source 1: YR.NO[41] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: WorldClimate[42] | |||||||||||||

Religion

Bury St Edmunds has a Gothic Revival cathedral and a large parish church, and used to have an abbey. Its Unitarian meeting house has existed since the early 18th century as a non-conformist chapel.[43]

Abbey

In the centre of Bury St Edmunds lie the remains of an abbey, surrounded by the Abbey Gardens. The abbey is a shrine to Saint Edmund, the Saxon King of the East Angles. The abbey was sacked by the townspeople in the 14th century and then largely destroyed during the 16th century with the Dissolution of the Monasteries, but the town remained prosperous throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, only falling into relative decline with the Industrial Revolution.

Cathedral

St James' parish church became St Edmundsbury Cathedral when the Diocese of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich was formed in 1914. The cathedral was extended with an eastern end in the 1960s. A new Gothic revival cathedral tower was built as part of a Millennium project running from 2000 to 2005. The opening for the tower took place in July 2005, and included a brass band concert and fireworks. Parts of the cathedral remain uncompleted, including the cloisters and some areas remain inaccessible to the public due to building work. The tower makes St Edmundsbury the most recently completed Anglican cathedral in the UK and was constructed using original fabrication techniques by six masons who placed the machine-cut stones individually as they arrived.

St Mary's Church

St Mary's Church is the civic church of Bury St Edmunds and the third largest parish church in England. It was part of the abbey complex and originally was one of three large churches in the town (the others being St James, now St Edmundsbury Cathedral, and St Margaret's, now gone). It is renowned for its magnificent hammer-beam "angel" roof, and is the final resting place of Mary Tudor, Queen of France, Duchess of Suffolk and favourite sister of Henry VIII. St Mary's is also home to the Chapel of the Suffolk and Royal Anglian Regiments.

St Edmund's Catholic Church

St Edmund's Catholic Church, located in Westgate Street, is the parish church of Bury St Edmunds. Founded by the Jesuits in 1763, the present church building is grade II listed. It was built in 1837. It is administered by the Diocese of East Anglia in its Bury St Edmunds deanery.

Culture

The Theatre Royal was built by National Gallery architect William Wilkins in 1819 and is the sole surviving Regency Theatre in the country.[44] The theatre, owned by the Greene King brewery, is leased to the National Trust for a nominal charge, and underwent restoration between 2005 and 2007. It presents a full programme of performances and is also open for public tours. An additional arts venue, The Apex, was built on the site of the former cattle market in 2010.[45]

Moyse's Hall Museum is one of the oldest (c. 1180) domestic buildings in East Anglia open to the public. It has collections of fine art, for example Mary Beale, costume, e.g. Charles Frederick Worth, horology, local and social history, including Witchcraft.[46] It holds an original death mask of William Corder who was hanged for the infamous 1827 Red Barn murder.

Smiths Row, a contemporary art gallery, is located in The Market Cross, restored by Robert Adam in the late 1700s. The Gallery was established in 1972 and today hosts a programme of changing contemporary art and craft exhibitions and events by British and international artists. Artists featured in the Gallery have included Cornelia Parker, David Batchelor, Anri Sala and Mark Fairnington.

The town holds several festivals a year. The largest festival is held in May and includes concerts, plays, dance, and lecturers culminating in fireworks. There is an annual Christmas Fair in the town, with food, drink, local crafts and fairground rides available, stretching from the Abbey Gardens to the Arc Shopping Centre. Bury St Edmunds is home to England's oldest Scout group, 1st Bury St Edmunds (Mayors Own).

Sport

The town's main football club, Bury Town, is the fourth oldest non-league team in England. They are members of the Isthmian League and have played at Ram Meadow since moving from Kings Road in the 1970s.[47]

Suffolk County Cricket Club play occasional games at the Victory Ground which is also the home ground of Bury St Edmunds Cricket Club. The cricket club previously played at Cemetry Road. Bury St Edmunds Rugby Football Club, has extensive history,[48] including the devastating plane crash that killed several members who had attended the 1974 Five Nations Championship match. Eastgate Amateur Boxing club was established in 1981. The club has been headquartered at various locations in and around the town, but are now training in an old WW1 gym in Rougham. West Suffolk Swimming Club formed in 1998 from the merger of two local swimming clubs and operates from pools in Bury St Edmunds, Haverhill and Culford. West Suffolk Athletics Club are based at the West Suffolk College sports ground.[49]

Local economy

.jpg)

Tourism

The Angel Hotel, a Georgian building on Angel Hill, was used by Charles Dickens while giving readings in the nearby Athenaeum and mentioned in The Pickwick Papers. Angelina Jolie also used the hotel as a base during the filming of Tomb Raider. A coaching inn has stood on this spot since the 15th century.[50]

Brewing

The nation's largest British-owned brewery, Greene King, is situated in Bury St Edmunds, as is the smaller Old Cannon Brewery. Just outside the town, on the site of RAF Bury St Edmunds, is Bartrums Brewery, originally based in Thurston.

The Greene King pub The Nutshell is situated in the centre of the town, and is one of several that claim to be Britain's smallest public house.[51]

Sugar beet

Bury's largest landmark is the British Sugar factory near the A14, which processes sugar beet into refined crystal sugar. It was built in 1925 when the town's MP, Walter Guinness, was Minister of Agriculture, and for many of its early years was managed by Martin Neumann, former manager of a sugar beet refinery in Šurany, then part of Czechoslovakia. Neumann was invited by the British government to oversee the refinement of sugar in Bury St Edmunds and, with his family, immigrated to the United Kingdom.

The refinery processes beet from 1,300 growers. 660 lorry-loads of beet can be accepted each day when beet is being harvested. Not all the beet can be crystallised immediately, and some is kept in solution in holding tanks until late spring and early summer, when the plant has spare crystallising capacity. The sugar is sold under the Silver Spoon name (the other major British brand, Tate & Lyle, is made from imported sugar cane). By-products include molassed sugar beet feed for cattle and LimeX70, a soil improver. The factory has its own power station,[52] which powers around 110,000 homes. A smell of burnt starch from the plant is noticeable on some days.[53]

Governance

Bury St Edmunds is the main town of the non-metropolitan district St Edmundsbury. Until 1974 Bury was the county town of West Suffolk, which then combined with East Suffolk to create the unified county that exists today. The council's main offices are located in the West Suffolk House, located in the town. Bury is also the main town of the Westminster parliamentary constituency also named Bury St Edmunds. Since becoming a single-seat constituency in 1885 it has always returned Conservative MPs. The current representative, Jo Churchill, was first elected in the 2015 General Election.[54]

Notable people

Notable people from Bury St Edmunds include the Bishop of Winchester and Lord High Chancellor of England Stephen Gardiner,[55] the 18th-century landscape architect Humphry Repton,[56] the hymn writer Alice Flowerdew, the micrographer and micromosaic artist Henry Dalton,[57] the artist and photographer William Silas Spanton, the author Maria Louise Ramé (also known as Ouida), the engineer and inventor Hiram Codd,[58] the cyclist James Moore, and the portrait painter Rose Mead. More recent figures from the town include artist and printer Sybil Andrews, artist and suffragette Helen Margaret Spanton, Canadian World War II general Guy Simonds, theatre director Sir Peter Hall, Canadian journalist and author Richard Gwyn, actors Bob Hoskins[59] and Michael Maloney,[60] speedway rider Danny Ayres,[61][62] Norwich City goalkeeper Andy Marshall, television presenter Becky Jago, digital writer and artist Chris Joseph, and writer/director Adrian Tanner.

Thomas Clarkson, a leading abolitionist, lived in the town for parts of his life. Though born in Bedford, actor John Le Mesurier grew up in the town.[63] Sir James Reynolds, junior, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer, lived in the town for much of his life and was buried in the Cathedral in 1739. Messenger Monsey, later physician to the Royal Hospital Chelsea and a man notorious in London society for his bad manners, practised in Bury in the 1720s.[64]

Notable bands from Bury St Edmunds include Jacob's Mouse, Miss Black America, The Dawn Parade and Kate Jackson of The Long Blondes.

Among notable people who have chosen to retire to or have second homes in Bury St Edmunds are former members of parliament and government ministers Lord Tebbit,[65] Sir John Wheeler,[66] Sir Eldon Griffiths,[67][68] and former senior Royal Air Force commander, Air Marshal Sir Reginald Harland.[69]

Education

Primary and secondary

At present Suffolk County Council operates a two-tier school system. However, state education in Bury St Edmunds and its catchment area form a three-tier system. On 17 February 2014, Suffolk County Council announced that its cabinet would be advised to recommend moving 20 schools in the town from three-tier to a two-tier system – including the closure of four middle schools.[70] Under the recommendations, Hardwick, Howard, St James and St Louis middle schools have all closed under the changes in September 2016.

Upper schools include Sybil Andrews Academy, County Upper School, King Edward VI, and St Benedict's. Middle schools include Howard Middle; St James; Westley Middle and Horringer Court Middle School, a training school.[71] The public school Culford School is located just north of the town in the village of Culford. State primary schools that serve the town are Howard Community Primary School, Westgate, Hardwick, Sebert Wood, Abbots Green, Sextons Manor, Guildhall Feoffment, St Edmunds, St Edmundsbury and Tollgate. The town also has two independent primary schools, South Lee School and Moreton Hall Preparatory School.

Higher and further

The town's largest further education provider is West Suffolk College, with over 10,000 students studying with the college every year.[72] The college is due to expand in September 2018, following a £7m government grant to help pay for an £8m energy, engineering and manufacturing teaching centre.[73] From 2015, students have been able to study foundation and undergraduate degrees at the University of Suffolk at West Suffolk College.[74]

Transport

Bury St Edmunds railway station serves the town, operated by Greater Anglia, on the Ipswich to Ely Line. Trains run seven days a week, every two hours to Peterborough and hourly to Ipswich and Cambridge. Trains from Peterborough continue to Ipswich after Bury St Edmunds. Onward train connections from Cambridge link with London King's Cross, London Liverpool Street and Stansted Airport, whilst Ipswich provides connections to Liverpool Street via Colchester.

The main interchange for bus and coach services for Bury St Edmunds is the bus and coach station, located on St Andrews Street North in the town centre. Bus services link the town centre with the main residential housing areas of the town. From November 2012 Sunday bus services were introduced over some of these routes. There are regular bus services to the neighbouring towns of Brandon, Cambridge, Diss, Haverhill, Ipswich, Mildenhall, Newmarket, Stowmarket, Sudbury and Thetford and many of the villages in between. Daily National Express coach services between Victoria Coach Station in London and Bury stop at the town's bus and coach station, as does the cross-country service between Clacton-on-Sea and Liverpool which travels via Cambridge, Peterborough, Leicester, Nottingham, Sheffield and Manchester.

Twin towns

Affiliations

- HMS Vengeance: Royal Navy Vanguard Class SSBN[75]

Literature

Bury St Edmunds is a location mentioned several times in the short ghost story The Ash Tree by M.R. James published in Ghost Stories of an Antiquary in 1904

Author Norah Lofts, though actually born in Shipham, Norfolk, bases many of her stories in Baildon, a fictionalised Bury St Edmunds.

See also

References

- "Town Population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- OS Explorer map 211: Bury St.Edmunds and Stowmarket Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton A2 edition. Publishing Date:2008. ISBN 978 0319240519

- "Magna Carta 800 – Bury St Edmunds". magnacarta800.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "Our Bury St. Edmunds". www.ourburystedmunds.com. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "Greene King – Beers & breweries – Our breweries – Greene King Brewery". www.greeneking.co.uk. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Dictionary, reference. "Borough". Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- dorothea, david. "Gothic Lessons: An Introduction". Archived from the original on 9 January 2004. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- "Prehistoric remains uncovered by archaeologists in Bury St Edmunds". East Anglian Daily Times. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Samuel Lewis, ed. (1848). "Burton-upon-Trent – Bushey". A Topographical Dictionary of England. London. pp. 452–460. Retrieved 9 February 2018 – via British History Online.

- J. Deck (1821). A Guide to the Town, Abbey and Antiquities of Bury St. Edmunds…. p. 2. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Edmund Gillingwater (1804). An Historical and Descriptive Account of St. Edmund's Bury, in the County of Suffolk…. J. Rackham. pp. 3–6. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition. 4. p. 868.

- Richardson, Douglas, Magna Carta Ancestry, Baltimore, Md., 2005, p.297.

- Hillaby, Joe. "Jewish Colonisation in the Twelfth Century," in The Jews in Medieval Britain: Historical, Literary, and Archaeological Perspectives, ed. Patricia Skinner (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2003), p. 31.

- Roth, Cecil. A History of the Jews in England (Oxford: Clarendon, 1978).

- Jocelin of Brakelond, Chronicle of the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, trans. Diana Greenway and Jane Sayers (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1989)

- Statham, Margaret (1988). The Book of Bury St Edmunds. Buckingham, England: Barracuda Books. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-86023-405-3.

- Thompson, Roger, Mobility & Migration, East Anglian Founders of New England, 1629–1640, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994.

- Thompson, Roger, Mobility & Migration, East Anglian Founders of New England, 1629–1640, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994, 18.

- Notestein, Wallace A History of Witchcraft in England from 1558 to 1718, American Historical Association 1911 (reissued 1965) New York Russell & Russell,OCLC 223043

- The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.III, London, John Knight, 1847, p.960

- "Numbers 37, 38 and 39 and Attached Walls". British listed buildings. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- "History of the Suffolk Regiment". Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "America in Suffolk". St Edmundsbury Borough Council. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- "On This Day, 3 March – 1974: Turkish jet crashes killing 345". BBC News Online. 3 March 1974. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

- "Welcome to One Suffolk". GB: Onesuffolk.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Thewlis, Jo. "Uproar at town council meeting". Bury Free Press. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- Marais, Kirsty. "Plug pulled on displays". Bury Free Press. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2008.

- "Local election results 2011". Bury Free Press. 9 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Beaumont, Mark (15 March 2013). "Conservatives regain control of Bury St Edmunds Town Council". Bury Free Press. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "St Edmundsbury Borough parish and town elections". Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "The Glen Chalk Caves, Bury St Edmunds" (PDF). English Nature. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- "HOUSING SUBSIDENCE (Hansard, 29 November 1978)". Hansard.millbanksystems.com. 29 November 1978. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Knott, Simon. "Suffolk Churches". Archived from the original on 3 December 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- British Listed Buildings. Moreton Hall School, Bury St Edmund's (English Heritage Building ID: 466967)

- "An Appeal for the Guildhall, Bury St Edmunds" (PDF). The Pilgrim Trust. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- "Old Fire Station Bury St Edmunds Suffolk | Flickr – Photo Sharing!". Flickr. 16 March 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- "Suffolk F&RS – Bury St Edmunds Fire Station | Flickr – Photo Sharing!". Flickr. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ">2003 Heatwave". doi:10.1256/wea.10.04A. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Winter weather: the coldest places in Britain". The Guardian. London. 21 December 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "Honington 1971–2000". YR.NO. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "1981–90 Rainfall". WorldClimate. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- 300 Years for Great Asset to the Town Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Bury Free Press

- "History of the Theatre Royal Bury St Edmunds". National Trust. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Apex aims to attract big names". 11 October 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- "Moyse's Hall Museum". St Edmundsbury Borough Council. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- "History of Bury Town Football Club – Founded in 1872". Archived from the original on 23 January 2018.

- "History – Bury St Edmunds RUFC". Pitchero.com. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Joanne O'Connor (29 March 2009). "Checking in: The Angel Hotel, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "BBC – Legacies – Architectural Heritage – England – Suffolk – Beer in a Nutshell – Article Page 1". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Industrial-scale evaporators Archived 26 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Chemical Engineering Department, University of Cambridge

- "Bury St Edmunds". Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Geater, Paul. "Jo Chuchhill says she is about reaping the benefits of hard work following huge majority win". Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- Mee, Arthur, The King's England, Suffolk, Our Farthest East, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1947 (reprint), 89.

- "Humphry Repton". Britain Express. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- "COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITIONS". The Museum of Jurassic Technology. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- "An Act of Codd". Digger Odell Bottle Price Guides. Digger Odell Publications. 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- "Bob" Hoskins on IMDb

- Michael Maloney on IMDb

- "RIDERS - A - British Speedway Official Website". www.britishspeedway.co.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Farrell, Paul (1 February 2020). "Danny Ayres Dead: Speedway Racer Dies at 33". Heavy.com. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Biography of John Le Mesurier on Tony Hancock.Org Archived 12 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 19 November 2008

- J. F. Payne/Michael Bevan: "Monsey, Messenger", ODNB (Oxford:OUP, 2004) Retrieved 27 December 2014. Pay-walled.

- Deborah Ross (3 October 2009). "Norman Tebbit: 'Margaret and I both made the same mistake. We neglected to clone ourselves'". The Independent. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "About Bury St Edmunds: Well-Known People, Films, Books, Music, Odd Facts". www.uniquewebsites.co.uk. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- "Sir Eldon Griffiths – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Interview with Mariam Ghaemi, Ipswich Evening Star, 25 March 2011

- "Air Marshal Sir Reginald Harland". www.telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph. 19 September 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- Jon Vale. "Bury St Edmunds: Four schools set to close as town moves towards controversial two-tier system". East Anglian Daily Times. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- "Directory of Training Schools". Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- "Key facts | News and Events| West Suffolk College". www.westsuffolkcollege.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Latest news | News and Events | West Suffolk College". www.westsuffolkcollege.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- "Key facts | News and Events| West Suffolk College". www.westsuffolkcollege.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bury St Edmunds. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bury St Edmunds. |

- St Edmundsbury Council

- Bury St Edmunds Past and Present Society

- We Love Bury St Edmunds! Reference Gallery