Charles Frederick Worth

Charles Frederick Worth (13 October 1825 – 10 March 1895) was an English fashion designer who founded the House of Worth, one of the foremost fashion houses of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He is considered by many fashion historians to be the father of haute couture.[3][4] Worth is also credited with revolutionising the business of fashion.

Charles Frederick Worth | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born | 13 October 1825 Bourne, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 10 March 1895 (aged 69) |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupation | Fashion designer |

| Known for | Creating haute couture |

Label(s) | House of Worth |

| Spouse(s) | Marie Augustine Vernet (1825–1898)[1] |

| Children | Gaston Lucien, Jean Philippe[1] |

| Parent(s) | William Worth and Ann Worth, née Quincey[1][2] |

Established in Paris in 1858, his fashion salon soon attracted European royalty, and where they led monied society followed. An innovative designer, he adapted 19th-century dress to make it more suited to everyday life, with some changes said to be at the request of his most prestigious client Empress Eugénie. He was the first to use live models in order to promote his garments to clients, and to sew branded labels into his clothing; almost all clients visited his salon for a consultation and fitting – thereby turning the House of Worth into a society meeting point. By the end of his career, his fashion house employed 1,200 people and its impact on fashion taste was far-reaching. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has said that his "aggressive self-promotion" earned him the title of the first couturier. Certainly, by the 1870s, his name was not just known in court circles, but appeared in women's magazines that were read by wide society.[5]

Worth raised the status of dressmaking so that the designer-maker also became arbiter of what women should be wearing. Writing on the history of fashion and, in particular, dandyism, in 2002, George Walden said: "Charles Frederick Worth dictated fashion in France a century and a half before Galliano".[6]

Early life

Charles Frederick Worth was born on 13 October 1825 in the Lincolnshire market town of Bourne[7] to William and Ann Worth. Some sources say he was their fifth and final child, and the only child other than his brother, William Worth III, to survive to maturity. Others say he was the family's third child. Charles' father was a solicitor – described as "dissolute" – and left his family in 1836 after ruining its finances, leaving his mother impoverished and without financial support.[8][9]

At the age of 11, Charles was sent to work in a printer's shop. After a year, he moved to London to become an apprentice at the department store of Swan & Edgar in Piccadilly. Seven years later, Lewis & Allenby, another leading British textiles store, employed Worth.[9]

Early career

In 1846, Charles Frederick Worth moved to Paris.[10] He arrived there speaking no French and with £5 in his pocket.[9] By the time his mother Ann Worth died in Highgate, London, in 1852, Worth was a sales assistant at Gagelin-Opigez & Cie, a prestigious Parisian firm that sold silk fabrics to the court dressmakers, also supplying cashmere shawls (then a ubiquitous accessory) and ready-made mantles.[1][9] It was here that he met Marie Vernet, who became his wife in 1851.[1][9]

Worth began sewing dresses to complement the shawls at Gagelin. Initially, these were simple designs, but his expert tailoring caught the eye of the store's clients. Eventually, Gagelin granted Worth permission to open a dress department, his first official entrance into the dressmaking world.[7][9][10] A 1958 article in The Times published shortly before a centenary exhibition in London to mark the opening of his Paris fashion house noted that the ambitious Englishman's ideas were almost too much for his employers: "The young Worth, full of ideas, was having such a success at Gagelin's that it was felt necessary to restrain his rashness".[9] His obituary, written by a Paris correspondent for The Times explained this comment in somewhat more detail, saying that he was refused a share in the Gagelin business, even though he had extended its activities into making up, rather than just selling, garments.[11] He had also helped build the company's international reputation by exhibiting prize-winning designs to both The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London and the Exposition Universelle in Paris four years later.[5] At the Paris exposition he had displayed a white silk court train embroidered in gold.[1]

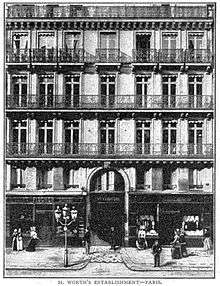

With a wife and two sons, Gaston Lucien (1853) and Jean Philippe (1856), Worth was eager to establish himself. By this stage, he was a known name.[10] He acquired a young Swedish business partner, Otto Gustaf Bobergh, and in 1858 the duo set up in business at 7 rue de la Paix, naming the establishment Worth and Bobergh.[7] Marie Vernet Worth played a key role from the start, both in the selling of the clothes and in introducing many new customers.[1]

House of Worth success

Success came fast from this point on; in 1860 a ball dress Worth designed for Princess de Metternich was admired by Empress Eugénie, who asked for the dressmaker's name and demanded to see him the next day.[9] In her memoirs, de Metternich commented: "And so...Worth was made and I was lost, for from that moment there were no more dresses at 300 francs each".[9] Worth promptly replaced Madame Palmyre as the favorite designer and dressmaker of the Empress.[12]

Worth offered a new approach to the creation of couture dresses, offering a plethora of fabrics (some from his former employer Gagelin) and expertise in tailoring.[10] Within a decade, his designs were recognized internationally and in high demand. By the 1870s, they were appearing in fashion magazines read by wider society.[5] Indeed, the influence of his designs may have spread even earlier via the fashion columns following Empress Eugénie's fashion choices in influential titles such as US magazine Godey's Lady's Book.[13]

Worth also changed the dynamic of the relationship between customer and clothes maker. Where previously the dressmaker (invariably female) would visit the client's home for a one-to-one consultation, with the exception of Empress Eugénie clients generally attended Worth's salon in rue de la Paix for a consultation and it also became a social meeting point for society figures.[9][14] His approach to marketing was also innovative – he was the first to use live mannequins in order to promote his gowns to clients.[15] His wife was his early model in the 1850s, leading Lucy Bannerman to describe Vernet as the world's first professional model.[16]

The fashion house had begun with 50 staff, but swelled over time to over 1,200 staff.[11] This was work that required painstaking attention to detail, finesse and craftsmanship: a Worth bodice might have up to 17 pieces of material to ensure a good fit on its wearer. Seamstresses would be assigned to different workshops where they specialized in, for instance, making sleeves, stitching hems or skirt making. Most of the sewing of Worth garments was by hand, although the advent of the early sewing machine meant some main seams could be stitched mechanically.[17]

Clientele

Worth became Empress Eugénie's official dressmaker and ensured the majority of her orders for extravagant evening wear, court dresses, and masquerade costumes.[7] She had him on call constantly to create dresses for events she attended.[10] As an example of the scale of Worth's business with the Empress, for the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, she had decided she needed 250 Worth dresses.[17] Apart from Empress Eugénie, he had numerous other royal clients, including Empress Elisabeth of Austria.[7]

Wealthy and socially ambitious women were drawn to Worth's showpiece creations.[7] Over time this included American clients; Worth loved working with them because his French language skills never reached fluency and, as he put it, American women: "have faith, figures, and francs – faith to believe in me, figures that I can put into shape, francs to pay my bills".[7] Wealthy Americans travelled to Paris to have their entire wardrobe made by Worth – and that meant morning, afternoon and evening dresses as well as what were termed 'undress' items such as nightgowns and tea gowns. He would also design special occasion garments, such as wedding dresses.[5] Alongside high society, the House of Worth also produced garments for popular stars such as Sarah Bernhardt, Lillie Langtry and Jenny Lind – who shopped there for both performance and private wear.[5] Prices at Worth were dizzying for the time; the last bill it issued to Princess de Metternich – who had commented on the end of the 300 franc dress once Worth acquired royal patronage – was for the sum of 2,247 francs. Her purchase had been one lilac velvet dress.[9]

Worth's appearance and manner

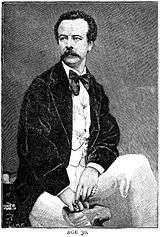

The most famous surviving portrait of Charles Frederick Worth shows him wearing a hat, fur-trimmed cape and cravat. It appears that he had adopted this distinctive dress from the 1870s. A contemporaneous account from a visitor to the home of "the Napoleon of costumiers" in 1874 described Worth's entrance to meet his party in: "a flowing grey robe that fell to his heels, lined with pale yellow, with a deep vest to match, and numerous other overlapping appliances that modified and gave elegance to a costume as unique as it was comfortable". The visitor, who described Worth as "not a bit 'Frenchy'", also noted that he was of medium height, strongly but not stoutly built with a dark moustache and had the appearance of a man who lived temperately.[18]

While the 1874 correspondent described Worth as "not a man to be afraid of if one has a liberal exchequer", it was implied that the couturier was not afraid to dictate to clients what they should wear: "Yet Mr Worth declares he has any amount of trouble with women – that they want to wear colours that don't become them and a superabundance of trimming that is far from good taste".[18] It appears Worth had the charm or gravitas to overcome his clients' requests for the wrong colour or trimming. His son Jean Philippe later recalled: "His practised eye discerned the color and style of robe that would most completely enhance a woman's charm, and with complete serenity she might leave the matter to him and give her mind to the contemplation of home affairs, her children and philanthropies".[19]

Fashion innovations

Charles Frederick Worth's dresses were known for their lavish fabrics and trimmings and for incorporating elements from period dress. He created unique pieces for his most important customers, but also prepared a variety of designs, showcased by live models, that could then be tailored to the client's requirements in his workshop.[5] Among his key innovations in women's fashion were to the line of garments and their length.

Garment shape

At the height of his success, Worth reformed the highly popular trend, the crinoline. It had grown increasingly large in size, making it difficult for women to manage even the most basic activities, such as walking through doors, sitting, caring for their children, or holding hands. Worth wanted to design a more practical silhouette for women, so he made the crinoline more narrow and gravitated the largest part to the back, freeing up a woman's front and sides. Worth's new crinoline was a major success.[20] Eventually, Worth abandoned the crinoline altogether, creating a straight gown shape without a defined waist that became known as the princess line.[20][21]

Shorter hemline

Worth created a shorter hemline – a walking skirt – at the suggestion of Empress Eugénie, who enjoyed long walks but not long skirts. This was initially seen as too radical, even shocking, because it was at ankle length, but its practical benefits meant it was adopted over time.[20][21] An 1885 example of the Worth 'walking dress' is held at the archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[22]

Franco-Prussian War

The Second Empire boomed, alongside Worth's brand, until 1870, when the Prussians invaded France. Worth closed his business for a year; he was able to reopen a year later, but wartime meant he had difficulty finding clientele, staying in business with lines of new maternity, mourning, and sportswear.[7] During the siege of Paris, he turned his salon into a military hospital.[11] At this stage, the partnership with Bobergh was dissolved – with the Swede returning to his home country.[1][11][23] In common with other fashion designers, the House of Worth was affected by the financial downturn of the 1880s.[7] Charles Frederick Worth found alternative sources of revenue in British and American customers and also turned his attention to encouraging the struggling French silk industry.[1]

By the late 1880s, Worth had established characteristics of a modern couture house – twice annual seasonal collections and brand extensions through the franchising of patterns and fashion plates. One of his biographers notes that he had also successfully fostered the myth of the "male 'style dicator'".[1]

Final years

Worth's sons Gaston and Jean, who had joined the business in 1874 to help with management, finance, and design, became increasingly active, leaving Worth free to take more time off in his later years; by this stage he had a variety of health problems, including migraines. On 10 March 1895, Charles Frederick Worth died of pneumonia at the age of 69.[24] He was celebrated enough to receive a variety of obituary notices. The notice in The Times said: "It is not a little singular that Worth...should take the lead in what is supposed to be a peculiarly French art".[11] Le Temps, meanwhile, suggested that Worth was of so artistic a temperament that he found England unsuited to his temperament and taste, and so gravitated to Paris, the city of light and beauty, to make his name.[25] This was a claim refuted in British society magazine Queen, which put his rise to prosperity down to perseverance, intelligence and industry; this article was later reprinted in the San Francisco Call.[25]

Although he was not in day-to-day control of House of Worth, he remained an active presence; his obituary in The Times noted that he had turned over the business some years earlier but: "he was to the last a constant frequenter of the establishment".[11] At the time of his death, he had both a house in the Champs-Élysées and a villa in Suresnes near the Bois de Boulogne. He was described as a "liberal contributor" to French charities and a keen collector of "artistic treasures and curiosities".[11] There seems little doubt that Worth had amassed a fortune; an 1874 visitor to this villa (who called it a château) described an abundance of faience china; a conservatory full of exotic plants; a winter garden and stables full of immaculately turned out horses. The gardens contained statuary and stones retrieved from Tuileries Palace (former home of his foremost patron Empress Eugénie) that were about to be incorporated into a new hothouse.[18]

Charles Frederick Worth's funeral was held at the Protestant Church in the Avenue de la Grande Armée.[11] He was buried in the grounds of his villa at Suresnes, according to the rites of the Church of England.[1] Marie Vernet Worth died three years later.[1]

Legacy and achievements

Although its founder was gone, the House of Worth was now an established entity; its most successful years were those flanking 1900. During this span of time, women were ordering 20–30 gowns at a time. By 1897, clients could order a garment by phone, by mail, or by visiting one of Worth's branch stores in London, Cannes, or Biarritz. Worth displayed garments at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, as it had at earlier great exhibitions.[7] The company's annual turnover was placed at around five million francs at the turn of the century.[1]

While Worth's obituary in The Times described him as a "dressmaker", he developed a framework for making and marketing clothes that would shape the haute couture industry that followed. As a biography for Museum of the City of New York notes: "Before Worth, the idea of a dress being recognizably the work of its creator didn't exist".[11][14] He regarded clothing as an art, and for the first time, designed clothing, not for a client's taste, but based on his impression of what women should wear. He presented finished model designs to clients and dress buyers in similar fashion to the modern-day haute couture designer, also using live models.[26] Worth was also the first designer to label his clothing, sewing his name into each garment he produced. This made him the first person to develop a distinct brand logo on clothing.[27]

Archives and commemoration

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has an archive of Charles Worth designs, including both sketches and garments.[28] In 1956, the House of Worth (by then amalgamated with the fashion house of Paquin) donated 23,000 drawings of dresses to the museum. Two years later, the V&A held a major retrospective to mark the centenary of the foundation of Charles Frederick Worth's business.[29]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art also holds an archive of his work, including several evening gowns.[30]

A Charles Worth Gallery opened in his home town at Bourne, Lincolnshire, containing a display of documents, photographs and artefacts at the Heritage Centre run by the Bourne Civic Society.

Gallery

.jpeg) Silk ensemble, 1862-1865

Silk ensemble, 1862-1865 1865 pink tulle ballgown created for Empress Elisabeth of Austria, as painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter.

1865 pink tulle ballgown created for Empress Elisabeth of Austria, as painted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Wedding dress trimmed with artificial pearls for wealthy American Clara Mathews, 1880

Wedding dress trimmed with artificial pearls for wealthy American Clara Mathews, 1880 Court dress designed for the Imperial Russian Court, about 1888. Green velvet and silver moiré.

Court dress designed for the Imperial Russian Court, about 1888. Green velvet and silver moiré. Early 1900s court presentation dress from Moyse's Hall Museum – House of Worth was at the height of its success at the turn of the century.

Early 1900s court presentation dress from Moyse's Hall Museum – House of Worth was at the height of its success at the turn of the century.

Notes and references

- Breward, Christopher. "Worth, Charles Frederick". oxforddnb. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Marriage certificate, Horbling, 2 December 1816, and other primary sources; A Portrait of Bourne by Rex Needle (2014), section "The family background of Charles Frederick Worth" ; note that de Marly, p.2 is incorrect.

- Jacqueline C. Kent (2003). Business Builders in Fashion – Charles Frederick Worth – The Father of Haute Couture The Oliver Press, Inc., 2003

- Claire B. Shaeffer (2001). Couture sewing techniques "Originating in mid- 19th-century Paris with the designs of an Englishman named Charles Frederick Worth, haute couture represents an archaic tradition of creating garments by hand with painstaking care and precision". Taunton Press, 2001

- "Charles Frederick Worth (1825–95) and the House of Worth". metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Walden, George; Howard, Philip (28 September 2002). "Fine and Dandy". The Times (67568).

- Coleman, Elizabeth Ann.

- A Portrait of Bourne by Rex Needle (2014), section "The family background of Charles Frederick Worth"

- "The Age of Worth". The Times (54190). 30 June 1958.

- de Marly, Diana

- "Obituary: Our Paris Correspondent". The Times (34522). 12 March 1895.

- Valerie Steele: Women of Fashion: Twentieth-century Designers, Rizzoli International, 1991

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2015). World Clothing and Fashion: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Social Influence (2nd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 282. ISBN 9780765683007. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Rennolds Milbank, Caroline. "Charles Frederick Worth". mcny.org. Museum of the City of New York. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Anniversaries". The Times (67706). 10 March 2003.

- Bannerman, Lucy (12 July 2008). "Not bad for just a coathanger: how the supermodel took over our magazines and wardrobes". The Times (69374).

- English, Bonnie (2013). A Cultural History of Fashion in the 20th and 21st Centuries (2nd ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 8. ISBN 9780857851369. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Charles Frederick Worth, the Paris Dressmaker" (3515). The Bradford Observer. 4 April 1874.

- Parkins, Ilya (2012). Poiret, Dior and Schiaparelli: Fashion, Femininity and Modernity. London: Berg (Bloomsbury). ISBN 9780857853264. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Saunders, Edith.

- "Charles Frederick Worth Industrializes Fashion". fashionencyclopedia.com. Fashion Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Walking dress". metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Charles Frederick Worth". designerindex.net. Archived from the original on 26 December 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- Olian, JoAnne. The House of Worth: The Gilded Age, 1860–1918. New York: Museum of the City of New York, 1982. Print.

- "The World's Great Milliner". 77 (132). San Francisco Call. 21 April 1895. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Gilles Lipovetsky, The Empire of Fashion: Dressing Modern Democracy, trans. Catherine Ponter (Princeton U.P., 1994)

- "House of Worth". Vogue. 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Charles Worth". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Worth Centenary Exhibition". The Times (54212). 25 July 1958.

- "Charles Frederick Worth". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

Bibliography

- Krick, Jessa. "Charles Frederick Worth (1825–1895) and The House of Worth." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2004)

- Worth, Gaston (1895). La Couture et la Confection des Vêtements de Femme. Paris, Imprimerie Chaix.

- Worth Jean-Philippe (1928), A Century of Fashion. Boston, Little Brown and Cie.

- Saunders, Edith (1955). The Age of Worth – Couturier to the Empress Eugenie. Indiana University Press.

- Brooklyn Museum (1962), The House of Worth. New York, The Brooklyn Museum.

- Museum of the City of New York (1982), The House of Worth, the gilded age 1860–1918. New York, Museum of the City of New York.

- Coleman, Elizabeth Ann (1989). The Opulent Era: Fashions of Worth, Doucet and Pingat. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500014769.

- de Marly, Diana (1991). Worth: Father of Haute Couture. Holmes & Meier Pub. ISBN 978-0841912427.

- de la Haye Amy, Mendes Valerie D. (2014), The House of Worth: Portrait of an Archive 1890-1914. Londres, Victoria & Albert Museum.

- DePauw Karen M., Jenkins Jessica D., Krass Michael (2015), The House of Worth: Fashion Sketches, 1916-1918. Mineola, Dover Publications & Litchfield Historical Society.

Further sources

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Frederick Worth. |

- Costumes designed by Charles Frédérick Worth at Chicago History Museum Digital Collections

- "Interactive timeline of couture houses and couturier biographies". Victoria and Albert Museum.

- Museum of the City of New York online exhibition of Worth couture garments

- A history of feminine fashion. Internet Archive. 1926. – Mid-1920s advertising booklet promoting Worth's role in 19th and early 20th century fashion.