Bogor

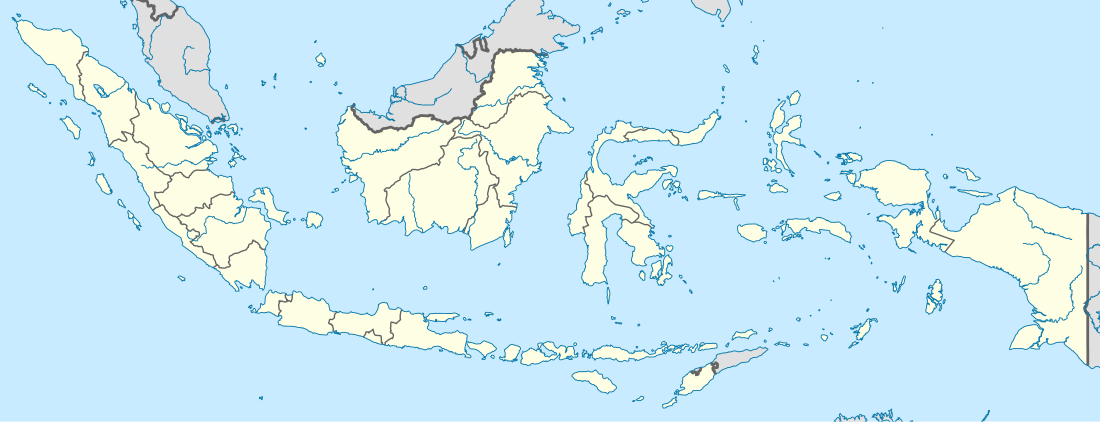

Bogor (Sundanese: ᮘᮧᮌᮧᮁ, Dutch: Buitenzorg) is a city in the West Java province, Indonesia. Located around 60 kilometers (37 mi) south of the national capital of Jakarta, Bogor is the 6th largest city of Jakarta metropolitan area and the 14th nationwide.[3] The city covers an area of 118.5 km2, and it had a population of 950,334 at the 2010 Census;[4] the latest official estimate (as at 2018[5]) was 1,096,828. Bogor is an important economic, scientific, cultural and tourist center, as well as a mountain resort.

Bogor ᮘᮧᮌᮧᮁ | |

|---|---|

| City of Bogor | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Dutch | Buitenzorg |

Clockwise from top: Bogor Palace, Great Mosque of Bogor, Bogor Botanical Garden, Kujang Monument | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): Kota Hujan (City of Rain) | |

| Motto(s): Dinu kiwari ngancik nu bihari seja ayeuna sampeureun jaga (Preserving the past, serving the people, and facing the future) | |

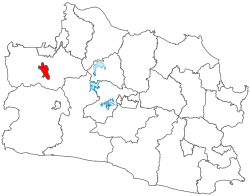

Location within West Java | |

| Coordinates: 6°35′48″S 106°47′50″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Founded | 1482 |

| Other names | Pakuan Pajajaran (1482−1746) Buitenzorg (1746–1942) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bima Arya (PAN) |

| • Vice Mayor | Dedie A. Rachim |

| Area | |

| • Total | 118.5 km2 (45.8 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 265 m (869 ft) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 1,096,828 |

| • Density | 9,300/km2 (24,000/sq mi) |

| [2] | |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (IWST) |

| Postcodes | 16100 to 16169 |

| Area code | (+62) 251 |

| Vehicle registration | F |

| Website | kotabogor.go.id |

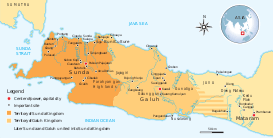

In the Middle Ages, the city served as the capital of Sunda Kingdom (Indonesian: Kerajaan Sunda) and was called Pakuan Pajajaran or Dayeuh Pakuan. During the Dutch colonial era, it was named Buitenzorg (meaning "Without worries" in Dutch) and served as the summer residence of the Governor-General of Dutch East Indies.

With several hundred thousand people living on an area of about 20 km2 (7.7 sq mi), the central part of Bogor is one of the world's most densely populated areas. The city has a presidential palace and a botanical garden (Indonesian: Kebun Raya Bogor) – one of the oldest and largest in the world. It bears the nickname "the Rain City" (Kota Hujan), because of frequent rain showers. It nearly always rains even during the dry season.

History

Precolonial period

The first mention of a settlement at present Bogor dates to the 5th century when the area was part of Tarumanagara, one of the earliest states in Indonesian history.[6][7][8] After a series of defeats by the neighboring Srivijaya, Tarumanagara was transformed into the Sunda Kingdom, and in 669, the capital of Sunda was built between two parallel rivers, the Ciliwung and Cisadane. It was named Pakuan Pajajaran, in old Sundanese meaning "a place between the parallel [rivers]", and became the predecessor of the modern Bogor.[9][10]

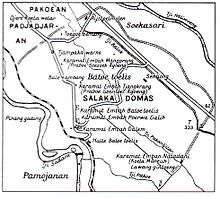

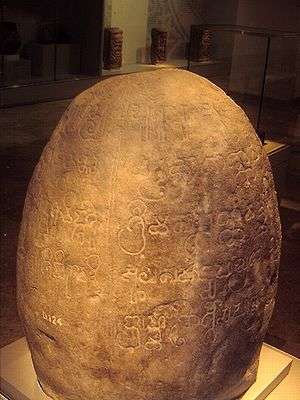

Over the next several centuries, Pakuan Pajajaran became one of the largest cities in medieval Indonesia with a population reaching 48,000.[10] The name Pajajaran was then used for the entire kingdom, and the capital was simply called Pakuan.[10][11][12][13][14] The chronicles of that time were written in Sanskrit, which was the language used for official and religious purposes, using the Pallava writing system, on rock stellas called prasasti.[7][15] The prasasti found in and around Bogor differ in shape and text style from other Indonesian prasasti and are among the main attractions of the city.[7]

In the 9–15th centuries, the capital was moving between Pakuan and other cities of the kingdom, and finally returned to Pakuan by King Siliwangi (Sri Baduga Maharaja) on 3 June 1482 – the day of his coronation. Since 1973, this date is celebrated in Bogor as an official city holiday.[16][17]

In 1579, Pakuan was captured and almost completely destroyed by the army of the Sultanate of Banten,[18][19] causing the existence of the State of Sunda to cease. The city was abandoned and remained uninhabited for decades.[10][16]

Colonial period

Dutch East India Company

In the second half of the 17th century, the abandoned Pakuan as most of West Java, while formally remaining under the Sultanate of Banten, gradually passed under control of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The formal transition occurred on 17 April 1684 by signing an agreement between the Crown Prince of Banten and the VOC.[20]

The first, and temporal, colonial settlement at Pakuan was a camp of lieutenant Tanoejiwa, a Sundanese employed by the VOC who was sent in 1687 to develop the area.[12][20][21] It was seriously damaged by the eruption on 4–5 January 1699 of the Mount Salak volcano (Indonesian: Gunung Salak). However, the concomitant forest fires removed much forest, leaving much area for the planned rice and coffee plantations.[12] In a short time, several agricultural settlements appeared around Pakuan, the largest being Kampung Baru (lit. "new village").[7] In 1701, they were combined into an administrative district; Tanoejiwa was chosen as the head of the district and is regarded as the founder of the modern Bogor Regency.[20][21]

The district was further developed during the 1703 Dutch mission headed by the Inspector General of the VOC Abraham van Riebeeck (the son of the founder of Cape Town Jan van Riebeeck and later Governor of Dutch East Indies).[12][20] The expedition of van Riebeeck performed a detailed study of the Pakuan ruins, discovered and described many archaeological artifacts, including prasasti, and erected buildings for the VOC employees.[21] The area attracted the Dutch by a favorable geographical position and mild climate, preferred over the hot Batavia which was then the administrative center of the Dutch East Indies.[21] In 1744–1745, the residence of the Governor-General was built in Pakuan which was hosting the government during the summer.[21]

In 1746, by the order of the Governor-General Gustaaf Willem van Imhoff, the Palace, a nearby Dutch settlement and nine native settlements were merged into an administrative division named Buitenzorg (Dutch for "beyond (or outside) concerns," meaning "without worries" or "carefree," cf. Frederick the Great of Prussia's summer palace outside Potsdam, Sanssouci, with the same meaning in French.)[22][23] Around the same time, the first reference to Bogor as the local name of the city was documented; it was mentioned in the administration report from 7 April 1752 with respect to the part of Buitenzorg adjacent to the Palace.[24] Later this name became used for the whole city as the local alternative to Buitenzorg.[22] This name is believed to originate from the Javanese word bogor meaning sugar palm (Arenga pinnata), which is still used in the Indonesian language.[24][25] Alternative origins are the old-Javanese word bhagar (meaning cow), or simply the misspelling of "Buitenzorg" by the local residents.[24]

The city grew rapidly in the late 18th – early 19th centuries.[21] This growth was partly stimulated by the temporary occupation of the Dutch East Indies by the United Kingdom in 1811–1815 – the British landed on Java and other Sunda Islands to prevent their capture by Napoleonic France which then conquered the Netherlands. The head of the British administration Stamford Raffles moved the administrative center from Batavia to Buitenzorg and implemented new and more efficient management techniques.[21][26]

Rule of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

After Buitenzorg was returned to the Dutch, it fell under the rule of the Kingdom of the Netherlands rather than VOC. The Buitenzorg Palace was reinstated as the summer residence of the Governor-General. A botanical garden was set up nearby in 1817, which was one of the world's largest gardens in the 19th century.[21][22][27][28]

.jpg)

On 10 October 1834, Buitenzorg was seriously damaged by another eruption of the Salak volcanoes caused by an earthquake.[21][29] Taking into account the seismic activity of the region, the governor's palace and office buildings constructed in 1840–1850 were built shorter but sturdier than those built prior to the eruption.[21] The Governor's decree of 1845 prescribed separate settlements of European, Chinese and Arab migrants within the city.[21]

In 1860–1880, the largest agricultural school in the colony was established in Buitenzorg. Other scientific institutions including a city library, natural science museum, biology, chemistry, and veterinary medicine laboratories were also constructed during this period. By the end of the 19th century, Buitenzorg became one of the most developed and Westernized cities in Indonesia.[12][21]

In 1904, Buitenzorg formally became the administrative center of the Dutch East Indies. However, real management remained in Batavia, which hosted most of the administrative offices and the main office of the governor.[7][22] This status was revoked in the administrative reform of 1924, which divided the colony into provinces and set Buitenzorg as the center of West Java Province.[7]

1942–1950

During World War II, Buitenzorg and the entire territory of Dutch East Indies were occupied by Japanese forces; the occupation lasted from 6 March 1942 until the summer of 1945.[30] As part of the efforts by the Japanese to promote nationalist (and thus anti-Dutch) sentiments among the local population the city was given the Indonesian name Bogor.[28] The city had one of the major training centres of the Indonesian militia PETA (Pembela Tanah Air – "Defenders of the Motherland").[31]

On 17 August 1945, Sukarno and Hatta proclaimed independence, but the Dutch regained control of the town and adjoining areas. In February 1948, Buitenzorg was included in the quasi-independent state of West Java,(Indonesian: Negara Jawa Barat) which was renamed Pasundan in April 1948 (Indonesian: Negara Pasundan). This state was established by the Netherlands as a step to transform their former colonial possessions in the East Indies into a dependent federation.[32][33] In December 1949, Pasundan joined the Republic of the United States of Indonesia (Indonesian: Republik Indonesia Serikat, RIS) established at the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference of 23 August – 2 November 1949.[33][34] In February 1950, as a result of defeat of Pasundan in a quick military conflict with the Republic of Indonesia, the city became part of Indonesia, as formalized in August 1950,[33][34] and its name was officially declared as Bogor.[16][35]

As part of Indonesia

As part of independent Indonesia, Bogor has a significant role in the cultural, scientific and economic development of the country and West Java in particular – in part due to the legacy of infrastructure built during the colonial period. Its special position was further reinforced by the transformation of the former summer residence of the governor-general into the summer palace of the President of Indonesia.[12][36] In the 1990s–2000s, the city regularly hosted various international events, such as ministry-level meetings of the Asia-Pacific institutions[37] and the APEC summit of 15 November 1994.[38] Since 2008, a Christian church congregation in Bogor has been embroiled with Islamic fundamentalists over the building permit for their new church.[39]

Geography, topography, geology

The city is situated in the western part of Java island, about 53 km south of the capital Jakarta and 85 km northwest of Bandung, the administrative center of West Java Province.[1] Bogor spreads over a basin near volcanoes Salak, which peaks at about 12 km south, and Mount Gede whose top is 22–25 km south-east of the city.[40] The average elevation is 265 meters, maximum 330 m, and minimum 190 meters above sea level.[1] The terrain is rather uneven: 17.64 km² of its area has slopes of 0–2°, 80.9 km² from 2° to 15°, 11 km² between 15° and 25°, 7.65 km² from 25° to 40° and 1.20 km² over 40°;[41] the northern part is relatively flat and the southern part is more hilly.[42]

The soils are dominated by volcanic sedimentary rocks.[42] Given the proximity of large active volcanoes, the area is considered highly seismic.[40] The total area of green space is 205,000 m², of which 87,000 m² are Bogor Botanical Gardens, 19,400 m² are taken by 35 parks, 17,200 m² by 24 groves and 81,400 m² are covered with grass.[43]

Several rivers flow through the city toward the Java Sea. The largest ones, Ciliwung and Cisadane, flank the historic city center. Smaller rivers, Cipakancilan, Cidepit, Ciparigi and Cibalok, are guided by cement tubes in many places.[40] It is worth noting that "ci" in the river names merely means "river" in Sundanese, and the actual name begins after it, but the "ci" is nevertheless included into national and international maps. There are several small lakes within the city, including Situ Burung (lit. Bird Lake; "Situ" meaning "Lake") and Situ Gede (lit. Great Lake), with the area of several hectares each. Rivers and lakes occupy 2.89% of the city area.[44]

Climate

Bogor has a tropical rainforest climate (Af) according to the Köppen climate classification,[45] and more humid and rainy than in many other areas of West Java – the average relative humidity is 70%,[40] the average annual precipitation is about 1700 mm, but more than 3500 mm in some areas.[40] Most rain falls between December and February. Because of this weather, Bogor has the nickname "Rain City" (Indonesian: Kota hujan).[46][47] The temperatures are lower than in coastal Java: the average maximum is 25.9 °C (cf. 32.2 °C in Jakarta). Daily fluctuations (9–10 °C) are rather high for Indonesia. The absolute maximum temperature was recorded at 38 °C and the minimum at 3 °C.[1]

| Climate data for Bogor, West Java, Indonesia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.3 (82.9) |

28.5 (83.3) |

29.3 (84.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.7 (76.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.1 (70.0) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 442 (17.4) |

378 (14.9) |

385 (15.2) |

428 (16.9) |

354 (13.9) |

225 (8.9) |

216 (8.5) |

240 (9.4) |

295 (11.6) |

390 (15.4) |

378 (14.9) |

355 (14.0) |

4,086 (161) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[45] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

The New American Cyclopaedia of 1867 reported Buitenzorg's population as being 320,756 including 9,530 Chinese, 650 Europeans, and 23 Arabs.[48]

Population

According to the national census held in May–August 2010, 949,066 people were registered in Bogor.[49] The average population density is about 8,000 people per km²; it reaches 12,571 persons per km² in the centre and drops to 5,866 people per km² in the southern part.[49] Based on BPS data,[2] Bogor population in 2018 was 1,096,828 people, suggesting a population density of 8,698 people/km2.

| Year | 1956 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1988 | 1999 | 2010 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 124,000[50] | 154,000[51] | 197,000[52] | 246,000[52] | 285,000[52] | 585,000[52] | 949,000[49] | 1,096,828[5] |

The rapid population growth in Bogor after 1960 is related to urbanization as well as the influx of workforce from other parts of the country.[52] The birth rate in 2009 was 563 children per 10,000 people, with the mortality value of 272. During the same year, 12,709 permanent resident moved in and 3,391 people left the city.[53] Men constituted 51.06% and women 48.94% of the population;[49] 28.39% of the inhabitants were under 15 years old, 67.42% were aged 15–65 years and 3.51% – over 65 years.[53] The 2005 estimate of the life expectancy is 71.8 years, which is the highest figure for West Java and one of the highest in Indonesia.[54]

Most population (87%) are Sundanese, with considerable numbers of Betawi, Javanese, Chinese and other, often mixed ethnicities.[55][56] Virtually all adults are fluent in Indonesian – the official language of the country. Sundanese is used at home and in some public areas and events – for example, the solemn speech of the mayor at the City Day celebration of 3 June 2010 was delivered in Sundanese.[56] The local dialect of Sundanese significantly differs from the classical version both lexically and phonetically.[57][58]

The majority of population (94%) are Muslims,[59] with just over 5% Christians. However, there are many Christian churches in the city,[60][61][62] as well as Buddhist (mostly in the Chinese community[63]) and Hindu communities.

| Religion | Adherents | Fraction of population (%) | Number of religious buildings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Islam | 838,533 | 92.64 | 715 |

| Protestantism | 30,807 | 3.40 | 27 |

| Roman Catholicism | 21,957 | 2.43 | 8 |

| Buddhism | 9,246 | 1.02 | 13 |

| Hinduism | 1,352 | 0.15 | 9 |

| Confucianism | 502 | 0.06 | 13 |

| Others | 2,736 | 0.30 |

Administrative divisions

Bogor City is surrounded by the Bogor Regency (kabupaten) but in itself is a separate municipality (kota),[16][64] making Bogor City an enclave within Bogor Regency. The city is divided into six districts (kecamatan), which contain 68 low-level administrative units, 31 of which have the status of settlement and 37 are villages.[65]

| English name | Indonesian name | Area in km² |

Population at 2010 Census |

Population at 2016 Estimate[66] |

Number of settlements and villages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Bogor | Kecamatan Bogor Utara | 17.72 | 170,443 | 196,051 | 8 |

| South Bogor | Kecamatan Bogor Selatan | 30.81 | 181,392 | 201,618 | 16 |

| East Bogor | Kecamatan Bogor Timur | 10.15 | 95,098 | 106,029 | 6 |

| West Bogor | Kecamatan Bogor Barat | 32.85 | 211,084 | 239,860 | 16 |

| Central Bogor | Kecamatan Bogor Tengah | 8.13 | 101,398 | 104,853 | 11 |

| Tanah Sareal | Kecamatan Tanah Sareal | 18.84 | 190,919 | 232,598 | 11 |

Administration

The city is headed by a mayor, who is elected by the citizens every five years, together with a vice-mayor; in the past, the mayor was appointed by the provincial administration.[64] Diani Budiarto became the first directly elected mayor of Bogor on 25 October 2008 and assumed his position on 7 April 2009.[67] Legislative power is provided by the City Council which consists of 45 people's representatives who are also elected by the residents for a 5-year term. Nine political parties consisting of five factions are represented in the Council.[68][69]

The coat of arms of Bogor is a rectangular heraldic shield with a pointed base and the side lengths ratio of 5:4, divided by a cross into four parts. The upper left quarter contains the National emblem of Indonesia – the mythical bird Garuda, in the upper right is the presidential palace, in the bottom left is the Salak volcano, and in the lower right is the national Sundanese dagger kujang. The inscription on top reads "KOTA BOGOR" which translates to "THE CITY OF BOGOR".[70]

Economy

Bogor has developed automotive chemical and food industries;[71] its outlying areas are used for agriculture.[72] During the colonization, Bogor was mostly producing coffee, rubber and high-quality timber. Chemical industry was introduced to the city at the end of the 19th century,[12][21] and car and metal production in the 1950s, during the industrialization of independent Indonesia. The fast economic development of the 1980s was slowed down by the crisis of the 1990s and recovered in the early 2000s; so the growth rate of the economy in Bogor was 5.78% in 2002, 6.07% in 2003 and 6.02% in 2009.[71] At the end of 2009, the Gross Regional Product (GRP) was 12.249 trillion IDR[73] (approximately US$1.287 billion[74]) and the investments amounted to 932.295 billion IDR.[73]

Despite the economical growth, the number of citizens living below the poverty level (defined by not only cash income, but also access to basic social services[75]) is increasing, primarily due to the inflow of poor residents of the surrounding rural areas. In 2009, 17.45% of the population lived below the poverty level, almost twice higher than in 2006 (9.5%)[73] Minimum wage is established by the West Java Governor at 2,658,155 IDR/month.[76]

| Branch of economy | Share in GRP (%)[77] |

|---|---|

| Trade, hotel and restaurant business | 30.14 |

| Industry | 28.2 |

| Financial services | 13.77 |

| Transport and communication | 9.7 |

| Customer services | 7.54 |

| Construction | 7.48 |

| Energy and water supply | 3.16 |

| Agriculture, fishing | 0.36 |

In 2008 there were 3,208 officially registered industrial enterprises in Bogor employing 54,268 people, more than half (32,237) of whom worked at the 114 largest companies.[78] The outskirts of the city contain about 3,466 hectares of agricultural area, including 111 hectares of water bodies used for fishery and fish farming.[72] The main crops are rice (1165 hectares as of 2007, the annual harvest in 2003 was 9,953 tonnes), various vegetables (772 acres, 8,296 tonnes), corn (382 acres, 6,720 tonnes) and sweet potato (480 acres, 3,480 tonnes).[79] The livestock sector has 25 registered companies (as of 2007) mostly breeding cows (more than 1000 animals yielding more than 2.61 million liters of milk), sheep (about 12,000), chickens (more than 642,000) and ducks (ca. 8,000).[80][81]

About 25–30 tonnes of various species of fish are produced per year by 4 registered companies. The fishes are mostly bred artificially, in ponds and paddy fields.[82] Breeding aquarium fish and also catching them in their natural habitat is an important industry sector, which yielded US$367,000 from 2008 export sales only, mostly to Japan and Middle East.[77] A substantial part of other Bogor production, 144 billion IDR in 2008, is exported. Examples are clothes and footwear (to US, EU, ASEAN, Canada, Australia, Russia), textiles (US, New Zealand), furniture (South Korea), car tires (ASEAN countries and South America), toys and souvenirs (Japan, Germany, Brazil), soft drinks (ASEAN countries and Middle East).[83][84] Most of the local sells are carried out via the eight major shopping centers, nine supermarkets and seven major markets.[83]

Transport

Bogor is a major transport center of Java. It contains 599.2 kilometers of roads (as of 2008) which cover 5.31% of the city area; 30.2 kilometers of the roads are of national and 26.8 km of prefectural importance.[85] The 22 transport lines are operated by 3,506 buses and minibuses. In addition, 10 bus routes connect the city with the nearest metropolitan area (4,612 buses) and 40 with other cities of West Java (330 buses).[86]

There are two major bus terminals, Baranangsiang and Bubulak. The former has an area of 22,100 m² and is dedicated to long-distance and freight traffic while the latter (area 11,850 m²) serves urban passenger routes.[87] A separate station is dedicated to tourist coaches and buses to the nearest Soekarno–Hatta International Airport in Jakarta, located about 55 kilometers from Bogor.[87] Recent years have seen a significant increase in the number of traditional Indonesian rickshaw (becak) at more than 2,000 units as of 2009.[88] The Bogor railway station was built in 1881, and currently serves about 50,000 passengers and has about 70 departures and 70 arrivals per day.[87] The Bogor Paledang railway station opened in 2013 to serve trains to Sukabumi.[89]

Housing and facilities

Residential buildings occupy 26.46% of the city, or 71.11% of its built-up area; 5–14-storey buildings dominate the central part and the outlying areas are mostly built up with single-storeyed houses.[90][91] The population rise in the 1990s–2000s due to the inflow of external workforce sharply increased the number of substandard housing, mainly on the outskirts of the city. More than half of the slums (1,242,490 m²) are located in northern Bogor, whereas their area is only 89,780 m² in southern part of the city.[91][92] To improve this situation, the city administration launched a program of construction of cheap housing types (light prefabricated houses) in the western Bogor. These houses combine reasonable rent ($22 per year[93]) at acceptable living conditions.[90]

Electricity to Bogor is supplied by Indonesian state company Perusahaan Listrik Negara, which serves the provinces of West Java and Banten. Electricity is provided by more than ten regional thermal and hydroelectric power plants via two local transformer stations located in the Bogor districts of Cimahpar and Cibilong.[94] Whereas most of the houses (excluding some slum areas) are provided with electricity, street lighting covers only 35.38% of the city (4,193 light sources, as of 2007), however, the number of street lights is increasing at an annual rate of 10–15%.[95]

As of 2009, only 47% of Bogor is provided with clean tap water through a centralized water supply systems managed by state-owned Tirta Pakuan.[96] The municipal system takes water from rivers Cisadane (1240 liters per second), and three natural sources: Kota Batu, Bentar-Kambing and Tangka (410 liters per second). Although, the water network has a total length of 741 kilometers and covers about 70% of the city, connection to it is often problematic for financial and technical reasons. More than half of residents use water wells or natural reservoirs.[96]

Garbage collection service covers 67% of the urban area. From about 800,000 m3 of waste per year, about 90% is buried at an external landfill at Galuga, about 7% is recycled for compost and about 3% is burned in five incinerators within the city.[97]

The seven cemeteries of Bogor are named by the city districts as Cilendek, Kayumanis, Situgede, Mulyaharja, Blender, Dreded and Gunung Gadung. The first six have the status of "public cemeteries" (Indonesian: Tempat pemakaman umum), and have no restrictions by religion or ethnicity. However, given the religious composition of Bogor, the cemeteries are predominantly Muslim, and Christian graves are located either in separate areas of cemeteries or in a small cemetery adjacent to churches.[98] Some mosques also have small burial plots.[99] Graves for poor and nameless are mostly located at Kayumanis,[100] and Gunung Gadung cemetery is restricted to Chinese residents.[101]

Education and science

Bogor is one of the major scientific and educational centers in Indonesia. A significant part of academic and research base was laid in the period of Dutch colonization. In particular, since the beginning of the 19th century there were established laboratories and professional schools focused primarily on improving the efficiency of the colonial agricultural;[12][21][22] In the late 19th – early 20th centuries have been established over major scientific institutions – the Research Institute and Rubber Research Institute of Forest.[102][103]

Similar to the prevailing profile of research and academic activity was retained in Bogor Indonesia and after gaining independence. As in the second half of 20th century, and in the 2000s strongest areas were agricultural science, Biology and Veterinary. The main educational and scientific center with the utmost national importance, is IPB University, which structure, in addition to educational facilities, includes dozens of research centers and laboratories.[104][105]

Bogor hosts the global headquarters of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), an international organization conducting research on forestry and human development.[106][107] The headquarters of the Organisation for the Preservation of Birds and their Habitat are also in Bogor.

| Education | Percentage of the population[77] |

|---|---|

| Less than 6 classes | 24.3 |

| Elementary school (grades 1–6) | 29.3 |

| Secondary school (grades 7–9) | 16 |

| High schools (grades 10–12) | 23.2 |

| Bachelor | 3.1 |

| Master and above | 4.1 |

| Type | Number of institutions (public/private) | Number of students | The number of teachers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kindergartens | 154 (1/153) | 7,194 (175/7,019) | 765 (11/754) |

| Schools for handicap children | 9 (0/9) | 408 (0/408) | 78 (0/78) |

| Elementary schools | 288 (248/40) | 97,794 (84,289/13,505) | 5,004 (4,267/737) |

| Secondary schools | 115 (19/96) | 43,153 (18,867/24,286) | 2,634 (892/1,742) |

| High schools | 50 (10/40) | 22,349 (9,450/12,899) | 1558 (566/992) |

| Technical schools | 63 (no data) | 28,375 (3,334/25,041) | 1826 (246/1,580) |

| Universities | 15 (5/10) | 16,998 (12,304/4,694) | 1,787 (1,225/562) |

The literacy rate in Bogor (98.7%) is rather high for Indonesia.[53] IPB University (Indonesian: Institut Pertanian Bogor) is the main agricultural university of the country. It was founded in 1963 based on the agricultural college, which was established back in the 19th century by the Dutch colonial administration.[104][108] The largest private universities are Pakuan, Juanda, Nusa Bangsa and Ibn Khaldun.[108] In addition to regular schools, there are over 700 Muslim schools (madrasah) and several Christian schools and colleges.[53]

Most scientific research in Bogor is carried out in agriculture, soil science, dendrology, veterinary and ichthyology.[104][105] More specific areas include natural pesticides and repellents, intercropping, industrial applications of essential oils and natural alkaloids, increasing yields of various kinds of pepper, improving preservation processes, etc.[109]

Culture

Bogor is one of the leading cities of Indonesia by the number of museums, some of which are among the oldest and largest in the country.[110] The Zoological Museum (Indonesian: Museum Zoologi) which was opened in 1894 by the Dutch colonial administration as an adjunct to the Botanic Gardens and contains thousands of exhibits.[111] Other prominent musea are more recent. So the museum of ethnobotany (Indonesian: Museum Etnobotani) was opened in 1982 and has more than 2000 exhibits;[112] museum of the earth (Indonesian: Museum Tanah, 1988) represents hundreds of soil and rock samples from different parts of Indonesia;[113] museum of the struggle (Indonesian: Museum Perjuangan, 1957) is devoted to the history of the Indonesian national liberation movement;[114] and Pembela Tanah Air Museum (1996) reflects the history of the Indonesian military militia PETA (Pembela Tanah Air – "Defenders of the Motherland") created during World War II by the Japanese administration.[115]

The city has a drama theater,[116] dozens of movie theaters, nine of which (as of mid-2010) are set up at international standards.[117] The presidential palace, administrative buildings and universities regularly host art exhibitions, and there are regular festivals of folk art, conferences and culture-related seminars, such as the Congress of Indonesian culture (Indonesian: Kongres Kebudayaan Indonesia) of 2008.[118]

Health

The first hospitals were established in Bogor in the first half of the 19th century by the Dutch authorities. By the early 20th century, there were several civilian hospitals, a military hospital,[119] and a large psychiatric hospital with doctors from Europe and North America.[120] In the 1930s, the Dutch Red Cross Society hospital became the largest in the city. Most of the existing hospitals and clinics are built in the 1980s–1990s.[121] They include 10 hospitals, 373 private clinics, 51 single-doctor clinics and 134 pharmacies and drug stores, and employ 274 general practitioners, 122 dentists, 74 sanitation doctors, 37 radiologists (X-ray), 141 gynaecologists, 32 nutritionists, 55 assistants, 710 nurses, 63 pharmacists and 99 doctors of other specialties.[53][121] 2 new hospitals are founded in 2014

The 12 hospitals of Bogor are:

- Hospital of the Indonesian Red Cross Society (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Palang Merah Indonesia) – general, the oldest in the city

- General Hospital of Bogor City (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Kota Bogor) – general, owned by the city government, formerly Karya Bhakti[122]

- Salak (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Salak) – general, owned by the Indonesian Army

- Atang Sanjaya (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit TNI AU Atang Sanjaya) – general, owned by the Indonesian Air Force, located in airbase area

- Bogor Medical Centre – general practitioners, private

- Islamic Hospital (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Islam) – general

- Azra (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Azra) – general

- Melania (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Melania) – women and children

- Hermina (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Hermina) – women and children

- Marzuki Mahdi (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Marzuki Mahdi) – infectious diseases and psychiatric hospital

- Mulia (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Mulia)- general

- Vania (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Vania)- general, founded in Nov 1st, 2014[123]

Media

Bogor has three daily Indonesian-language newspapers[124] – "Radar Bogor", founded in 1998 and "Pakuan Raya" in founded in 2005 and Jurnal Bogor, founded in 2008. they print in about 25,000 copies and have electronic versions. Bogor offices also partly print part some Javanese and national newspapers. There are a few magazines and scientific publications of the local universities.

The two municipal TV channels, "Bogor-TV" and "Megasvara TV" broadcast at UHF channel 25 over the city and nearby areas of West Java.[125] There are also at least 30 local radio stations, of which 20 are in the FM and 10 in the AM range.[126]

Sport

As of March 2010, the Bogor teams were registered in 28 sports to participate in national and regional competitions conducted by the National Sports Committee of Indonesia (Indonesian: Komite Nasional Olahraga Indonesia). Their achievements are regarded as poor. At the Java competitions, Bogor athletes took 5 gold medals instead of the planned 42.[127][128] The largest among 15 sports organizations[53] is the Bogor Football Union (Indonesian: Persatuan Sepakbola Bogor), headed by the current Mayor Diani Budiarto. The local football team "PSB Bogor" never took prizes in the national championships.[129] The local Stadium Pajajaran can accommodate 25,000 spectators.[130]

Travel and places

On a national tourism exhibition of 2010 in Jakarta, Bogor was recognized as the most attractive tourist city of Indonesia.[131] The city and its surrounding area are visited by about 1.8 million people per year, of whom more than 60,000 are foreigners.[132] The main tourist attraction is the Bogor Botanical Garden. Founded in 1817, it contains more than 6,000 species of tropical plants. Besides, about 42 bird species breed within the garden, although this number is declining and was 62 before 1952.[133] The garden's 87-hectare area within the city was supplemented in 1866 by a 120-hectare park in suburban town of Cibodas.[134][135] Much of the original rainforest was preserved within the garden providing specimens for scientific studes. Besides, the garden was enriched by collections of palms, bamboos, cacti, orchids and ornamental trees.

It became famous in the late 19th century and was visited by naturalists from abroad to conduct scientific research. For example, the Russian St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences had a Buitenzorg scholarship for young scientists to work at Bogor.[134] The staff of Bogor garden also administer three other major gardens of Iindonesia: the Cibodas Botanical Garden founded 1862 in West Java, the Purwodadi Botanical Garden in East Java and the Bali Botanic Garden founded in 1959 on Bali island.[136]

Another tourist attraction is the presidential palace with the total area of 28 hectares, including 1.8492 hectares of the palace buildings. The palace is surrounded by a park with a small pond.[134][137] The park is home to a herd of tame deer and is open to the public most of the year. The palace is accessible during holidays, such as the City Day and Independence Day; it has a collection of 450 paintings and 360 sculptures.[134]

The city and its suburbs contain dozens of medieval stone stelae (prasasti). Fifteen prasasti of the greatest historical and cultural value are collected in a special pavilion in the district of Batutulis.[138] In the western part of Bogor there is a large lake Gede (area 6 hectares) surrounded by the reserved forest area and a forest park. In the protected area there are several research facilities, and the recreation areas host sports activities, boating and fishing.[139][140]

On the territory of the botanic garden, there is a cemetery established in 1784.[141] It contains 42 historical graves of the Dutch colonial officials, military officers and scientists, who served in Bogor, Jakarta and other cities in West Java from the late 18th to early 20th centuries.[141] Nearby, there are three graves of the early Sunda Kingdom (15th century): the wife of the founder of Bogor Silivangi, Galuh Mangku Alam, vizier Ba'ul and commander Japra. The locals regard these individuals as the city's patrons.[142]

Other historical places are Bogor Cathedral – built in 1750, it is one of the oldest operational Catholic Churches in Indonesia,[143] and the Buddhist temple Hok Tek Bio, built in 1672 in the classical South Chinese style. It is the first Buddhist temple of Bogor and one of the oldest in Indonesia.

Nearby is the Jaksa Waterfall.

Recently Bogor launched a new bus service that can accommodate 25 passengers to look around outside of Bogor Botanical Garden. The bus route will start from Botanical Square and end at the same place. The service was unveiled by the mayor of Bogor Bima Arya on 1 January 2017. This bus is called UNCAL which means "Unforgettable City Tour at Lovable City".

Besides all the tourist attractions above, Bogor also offers a variety of shopping malls or stores: Botani Square, Bogor Trade Mall, Lippo Plaza, Plaza Indah Bogor, etc.[144]

Pura Kajatkarta Hindu temple

The Pura Kagatkarta is a striking Hindu temple located not far to the west of Bogor. It is on the northern slopes of Gunung Salak in Ciapus, Tamansari subdistrict, and is easily accessible by car from Bogor.

Famous people born in Bogor

The list includes only people with Wikipedia pages in at least three languages.

- Adriaan Fokker (1887–1972) – Dutch physicist

- Hein ter Poorten (1887–1968) – Commander of the armed forces of the Dutch East Indies in the early second World War II

- Ru den Hamer (1917–1988) – Dutch Olympic water polo player

- Ayu Utami (b. 1968) – Indonesian writer

- Rudi Soedjarwo (b. 1971) – Indonesian playwright

- Suzzanna (1942–2008) – Indonesian actress

- Dr. Syed Muhammad Naqūib al-Aṭṭas (5 September 1931–) – Muslim scholar

- Jimi Bellmartin (b. 1949) – Dutch singer and Voice Senior winner

Sister cities

Further reading

- "Klenteng Hok Tek Bio". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

References

- "Letak geografis kota Bogor". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "Penduduk Kota Bogor". Badan Pusat Statistik Kota Bogor. Badan Pusat Statistik Kota Bogor. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- http://www.depkes.go.id/downloads/Penduduk%20Kab%20Kota%20Umur%20Tunggal%202014.pdf Archived 8 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine Estimasi Penduduk Menurut Umur Tunggal Dan Jenis Kelamin 2014 Kementerian Kesehatan

- Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

- "BPS-Laci 3.0". laci.bps.go.id. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Yoseph Iskandar (1997). Sejarah Jawa Barat: Yuganing Rajakawasa (in Indonesian). Bandung: Geger Sunten. p. 14.

- "History of Bogor City". Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- Hadinoto, Pandji R. (26 June 2009). "Jakarta : Lima Belas Abad Menghadang Banjir" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Pakuan ibukota Kerajaan Sunda" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Bogor Tunas Pajajaran" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- "Sundanese people" (in Russian). Etnolog.ru. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Asal dan arti nama Pakuan" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 29 May 2010.

- "Юго-Восточной Азии цивилизация (Civilization of South-East Asia)" (in Russian). Kolier Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Bulat, Vladmir. "Political map of Eurasia, 700 AD". Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- "Bogor" (in Russian). Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- "Sejarah pemerintahan di kota Bogor". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "Sejarah kota Bogor" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- Всемирная история (World History) (in Russian). 4. Moscow: Мысль. 1958. p. 654.

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 2. Moscow. 1969–1978. p. 612.

- "Peraturan Daerah Kota Depok nomor 01 tahun 1999" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Walikota Depok. 1999. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- "Cerita perjalanan" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 770.

- "Sejarah wilayah Bogor". Unofficial Website of Bogor. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- "Pembukaan. 1. Asal dan Arti Nama Bogor" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Balai Pustaka. 1996. p. 140.

- "RAFFLES, Thomas Stamford. The History of Java". Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Sharon E. Kingsland (2005) The evolution of American ecology, 1890–2000, ISBN 0-8018-8171-4, p. 30

- V. M. Kotlyakov, ed. (2006). Богор (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: Dictionary of modern geographical names. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Bogor Palace to hold open house for city anniversary celebration". Jakarta Post. 6 March 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- Solahuddin, Edwin (28 February 2009). "Japanese Invaded Java". VIVA news. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Sejarah Perjuangan Ummat Islam Indonesia" (in Indonesian). 6 January 2004. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Indonesian States 1946–1950". Ben Cahoon. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Всемирная история. 12. Moscow: Мысль. 1979. pp. 356–359.

- Pimanov, К. "Indonesia" (in Russian). Энциклопедия "Кругосвет" (Encycloopedia Krugosvet). Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Undang-Undang no. 16 tahun 1950 tentang pembentukan daerah-daerah kota besar dalam lingkungan propinsi Djawa Timur, Djawa Tengah, Djawa Barat dan dalam daerah istimewa Jogjakarta (Law of Indonesia No. 16 1950 on creation of settlements in Eastern Java, Central Java, Wester, Java and Jacarta)" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "Istana Bogor" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Sarasvati, Ayu (29 October 2007). "Report on Climate Change Ministerial in Bogor to Prepare for Bali". TWN. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- "APEC Economic Leaders' Declaration of Common Resolve". 15 November 1994. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Haryanto, Ulma (15 January 2011). "Delight After Indonesia's Highest Court Backs Bogor Church". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- "Potensi Kota". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Topografi". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- "Geologi". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- "Taman Kota". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Penggunaan Lahan". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- http://en.climate-data.org/location/3930/

- "Direktori & Informasi Lingkungan Bogor" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "Kota Hujan" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- George Ripley; Charles Anderson Dana (1867). The New American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge. 4. Appleton.

- "Hasil Olah Cepat Sensus Penduduk 2010, Warga Kota Bogor 949 Ribu Jiwa". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 16 August 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- Small Soviet Encyclopedia. 1. Moscow. 1958. p. 1084.

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 3. Moscow. 1969–1978. p. 449.

- Manurung, Teguh V.A. (2008). "Kehidupan Masyarakat Kota Bogor" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Profil Daerah Kota Bogor" (in Indonesian). 15 January 2010. Archived from the original on 2 October 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- "Profil Kesehatan 2006" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- "Info CPNS Bogor 2010". Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Priliawito, Eko (3 June 2010). "Warga Padati Balaikota Rayakan HUT Bogor" (in Indonesian). Metro. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- Sutawijaya, Alam. "Struktur Bahasa Sunda Dialek Bogor" (in Indonesian). Pusat bahasa (Ministry of Education and Culture of Indonesia). Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- "Bahasa Sunda Bogor lebih keras" (in Indonesian). Forum Detik. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- "Selepas Sahur Ribuan Umat Islam Penuhi Masjid". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 2 September 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Portal Keuskupan Bogor" (in Indonesian). Keuskupan Bogor. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Gereja Kristen Pasundan Bogor" (in Indonesian). GKP Bogor. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- "Direktori jemaat" (in Indonesian). Gereja Protestan di Indonesia bagian Barat. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- Darmasapurtra, Metta (22 May 2006). "Agama-Agama Tak Mungkin Disamakan" (in Indonesian). Jaringan Islam Liberal. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- "Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 32 Tahun 2004 Tentang Pemerinahan Daerah (Indonesian Law No.32 2004 on Local Administration)" (in Indonesian). Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- "Struktur organisasi pemerintahan daerah kota Bogor". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 26 February 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2019.

- "Kepala daerah". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- "Profil Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Kota Bogor 2009". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- "Fraksi". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- "Lambang Kota Bogor". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- "Industri". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Hamdi, Saeful (22 December 2009). "Sektor Perdagangan" (in Indonesian). Badan Pelayanan Perizinan Terpadu Kota Bogor. Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Wakil Walikota Sampaikan Kebijakan Umum APBD 2011". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 4 August 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- "Kota Bogor". USD (US Dollars) to IDR (Indonesian Rupiahs) exchange rate for 1 November 2009. 1 November 2009. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- "Masalah Kemiskinan". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- http://regional.kompas.com/read/2014/11/22/07020041/Ini.UMK.Jawa.Barat.2015

- "Kota Bogor" (in Indonesian). Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and Soegeng Sarjadi Syndicate. 2009. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Hamdi, Saeful (22 December 2009). "Sektor Industri" (in Indonesian). Badan Pelayanan Perizinan Terpadu Kota Bogor. Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Agribisnis". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 23 January 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- "Target dan Realisasi Panen Tanaman Padi, Palawija dan Hortikultura". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "Domba..." Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "Jumlah RTP di Kolam Air Deras..." Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- Hamdi, Saeful (22 December 2009). "Sektor Perdagangan" (in Indonesian). Badan Pelayanan Perizinan Terpadu Kota Bogor. Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Ekspor". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- Hamdi, Saeful (22 December 2009). "Sektor Pemukiman dan Prasarana Wilayah" (in Indonesian). Badan Pelayanan Perizinan Terpadu Kota Bogor. Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Jumlah Angkutan Umum Kota Bogor". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "Untuk melayani..." Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- "Becak Tambah Banyak di Bogor" (in Indonesian). Kompas. 23 October 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- "PT Kereta Api Aktifkan Kembali KA Bogor-Sukabumi". Republika Online (in Indonesian). 10 November 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Rumah Susun Sewa". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 23 January 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Kondisi Geografis" (in Indonesian). Badan Perencana Pembangunan Daerah Kota Bogor. 9 February 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Kawasan Kumuh". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Foreign exchange rate data – Indonesian rupiah – IDR – Indonesia" (in Indonesian). RatesFX. 8 September 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Info PLN" (in Indonesian). PT PLN (Persero) Distribusi Jawa Barat dan Banten. 2010. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Penerangan Kota". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "PDAM Kota Bogor Tirta Pakuan" (in Indonesian). PDAM Kota Bogor Tirta Pakuan. 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Layanan Kebersihan". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 1 March 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Pemkot Tambah Lahan TPU" (in Indonesian). PDAM Kota Bogor Tirta Pakuan. 5 February 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- Damayanti, Rizky (28 August 2010). "Makam Abah Falak Sering Dikunjungi" (in Indonesian). Kampoeng Bogor. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- Paragoan, Wiana (5 February 2010). "Antisipasi Korban Lalin saat Lebaran, Lubang Kuburan Disiapkan" (in Indonesian). Republika. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- Pardede, Muhammad Tamim (12 June 2010). "Ki Gendeng Pamungkas... Posko Komite Gerakan Anti Cina" (in Indonesian). Beta Politikana. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- Honig, Pieter; Verdoorn, Frans. "Transcultural Science and Scientists in the Netherlands Indies". Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Buwalda, Pieter". National Herbarium Nederland. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Institut Pertanian Bogor" (in Indonesian). 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "Lembaga Penelitian". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "About CIFOR". Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Groupe Consultatif pour la Recherche Agricole Internationale" (in Spanish, French, German, and Russian). Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Universities of Indonesia". 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "Morphological Characteristic of Indian Galanga Flower (Kaemferia galanga L.)" (in Indonesian). Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Pertanian (Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture). 25 August 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- "Bidang Kebudayaan" (in Indonesian). Dinas Informasi, Kepariwisataan dan Kebudayaan Kota Bogor. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Museum Zoologi". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Museum Etnobotani". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Museum Tanah". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Museum Perjuangan". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Museum PETA". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Drama dan Teater" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- "Bogor" (in Indonesian). Cinema 21. 3 July 2010. Archived from the original on 15 May 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- Saranta, Anggit (15 December 2008). "Bogor tetap Buitenzorg" (in Indonesian). Kampoeng Bogor. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- "History of Bogor Botanic Garden". Archived from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Transcultural Psychiatry: Personal Experiences and Canadian Perspectives". June 2000. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Direktori Bogor: Rumah Sakit" (in Indonesian). 2010. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Koran Daerah – Jawa (list of regional newspapers of Java)" (in Indonesian). Endonesia. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- "Local Television Stations in Indonesia". Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- "Radio Stations in Bogor, West Java, Indonesia". Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- "Tembus Lima Besar, KONI Kota Bogor Targetkan Raih 42 Medali Emas". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 29 June 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- "Jelang Penutupan Sabet Lima Emas". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- "Musta PSB Tujuk Walikota Bogor Sebagai Ketua PSB". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- "Stadiums in Indonesia". Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- "Bogor Terpilih Jadi Kota Pariwisata" (in Indonesian). Bogor.net – Media online Bogor. 1 June 2010. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- "Wisatan ke Bogor..." (in Indonesian). Berita Wisata. 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- Patrick L. Osborne Tropical ecosystems and ecological concepts, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-64523-9 p. 277

- "Tentang Kebun Raya Bogor (Botanic Garden of Bogor)" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "Kebun Raya Bogor". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "Indonesia Botanical Gardens". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- "Istana Bogor". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 24 April 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "Batutulis". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "Situ Gede, Salah Satu Potensi Wisata Alam Kota Bogor" (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. Archived from the original on 26 June 2006. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- "Situ Gede". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- Aroengbinang (15 January 2010). "Kuburan Belanda". Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Menengok Mbah Japra 'Penjaga' Kota Bogor" (in Indonesian). MSN News. 9 June 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- "Gereja Katedral". Official Site of Bogor City (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kota Bogor. 28 April 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- "PARIWISATA : Wisata Belanja". direktori.kotabogor.go.id. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bogor. |

- Official Site (in Indonesian)

- Poentjak Weg (in Indonesian)

- Website Sejarah Bogor (in Indonesian)

- (in Indonesian)