Bristol Beaufighter

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter (often called the Beau) was a multi-role aircraft developed during the Second World War by the Bristol Aeroplane Company in the UK. It was originally conceived as a heavy fighter variant of the Bristol Beaufort torpedo bomber. The Beaufighter proved to be an effective night fighter, which came into service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Battle of Britain, its large size allowing it to carry heavy armament and early airborne interception radar without major performance penalties.

| Type 156 Beaufighter | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Beaufighter belonging to 31 Squadron of RAAF | |

| Role | Heavy fighter / strike aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Bristol Aeroplane Company |

| First flight | 17 July 1939 |

| Introduction | 27 July 1940 |

| Retired | 1960 |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force Royal Canadian Air Force Royal Australian Air Force |

| Produced | May 1940–1946 |

| Number built | 5,928 |

| Developed from | Bristol Beaufort |

The Beaufighter was used in many roles; receiving the nicknames Rockbeau for its use as a rocket-armed ground attack aircraft and Torbeau as a torpedo bomber against Axis shipping, in which it replaced the Beaufort. In later operations, it served mainly as a maritime strike/ground attack aircraft, RAF Coastal Command having operated the largest number of Beaufighters amongst all other commands at one point. The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) also made extensive use of the type as an anti-shipping aircraft, such as during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

The Beaufighter saw extensive service during the war with the RAF (59 squadrons), Fleet Air Arm (15 squadrons), RAAF (seven squadrons), Royal Canadian Air Force (four squadrons), United States Army Air Forces (four squadrons), Royal New Zealand Air Force (two squadrons), South African Air Force (two squadrons) and Polskie Siły Powietrzne (Free Polish Air Force; one squadron). Variants of the Beaufighter were manufactured in Australia by the Department of Aircraft Production (DAP); such aircraft are sometimes referred to by the name DAP Beaufighter.

Development

Origins

The concept of the Beaufighter has its origins in 1938. During the Munich Crisis, the Bristol Aeroplane Company recognised that the Royal Air Force (RAF) had an urgent need for a long-range fighter aircraft capable of carrying heavy payloads for maximum destruction.[1] Evaluation of the Beaufort concluded that it had great structural strength and stiffness in the wings, nacelles, undercarriage and tail, so that the aircraft could be readily developed further for greater speed and manoeuvrability akin to a fighter-class aircraft.[1] The Bristol design team, led by Leslie Frise, commenced the development of a cannon-armed fighter derivative as a private venture. The prospective aircraft had to share the same jigs as the Beaufort so that production could easily be switched from one aircraft to the other.[1]

As a torpedo bomber and aerial reconnaissance aircraft, the Beaufort had a modest performance. To achieve the fighter-like performance desired for the Beaufighter, Bristol suggested that they equip the aircraft with a pair of their new Hercules engines, capable of around 1,500 hp, in place of the 1,000 hp Bristol Taurus engines on the Beaufort. The Hercules was a considerably larger and more powerful engine which required larger propellers. To obtain adequate ground clearance, the engines were mounted centrally on the wing, as opposed to the underslung position on the Beaufort.[1] In October 1938, the project, which received the internal name Type 156, was outlined. In March 1939, the Type 156 was given the name Beaufighter.[2]

During early development, Bristol had formalised multiple configurations for the prospective aircraft, including variations such as a proposed three-seat bomber outfitted with a dorsal gun turret with a pair of cannons, the Type 157 and what Bristol referred to as a sports model, with a thinner fuselage, the Type 158.[2] Bristol proceeded to suggest their concept for a fighter development of the Beaufort to the Air Ministry. The timing of the suggestion happened to coincide with delays in the development and production of the Westland Whirlwind cannon-armed twin-engine fighter.[3] While there was some scepticism that the aircraft was too big for a fighter, the proposal was given a warm reception by the Air Staff.[1]

The Air Ministry produced draft Specification F.11/37 in response to Bristol's suggestion for an "interim" aircraft, pending the proper introduction of the Whirlwind. On 16 November 1938, Bristol received formal authorisation to commence the detailed design phase of the project and to proceed with the construction of four prototypes.[1] Amongst the design requirements, the aircraft had to be able to accommodate the Rolls-Royce Griffon engine as an alternative to the Hercules and that it have maximum interchangeability between the two engines, which would feature removable installations.[4]

Bristol began building an initial prototype by taking a partly-built Beaufort out of the production line. This conversion served to speed progress; Bristol had promised series production in early 1940 on the basis of an order being placed in February 1939. Designers expected that maximum re-use of Beaufort components would speed the process but the fuselage required more work than expected and had to be redesigned.[5] Perhaps in anticipation of this, the Air Ministry had requested that Bristol investigate the prospects of a "slim fuselage" configuration.[4] Since the "Beaufort cannon fighter" was a conversion of an existing design, development and production was expected to proceed more quickly than with a new one. Within six months the first F.11/37 prototype, R2052, had been completed.[2] A total of 2,100 drawings were produced during the transition from Beaufort to the prototype Beaufighter, more than twice as many were created during later development, between the prototype Beaufighter and the fully operational production models. Two weeks prior to the prototype's first flight, an initial production contract for 300 aircraft under Specification F.11/37 was issued by the Air Ministry, ordering the type "off the drawing board".[2]

Prototypes and refinement

On 17 July 1939, R2052, the first, unarmed, prototype, conducted its maiden flight, a little more than eight months after development had formally started.[2] The rapid pace of development is partly due to the re-use of many elements of the Beaufort design along with frequently identical components. R2052 was initially operated by Bristol for testing purposes while it was based at Filton Aerodrome.[2] Early modifications to R2052 included stiffening of the elevator control circuit, increased fin area and lengthening of the main oleo strut of the undercarriage to better accommodate weight increases and hard landings.[6]

During the pre-delivery trials, the first prototype R2052, powered by a pair of two-speed supercharged Hercules I-IS engines, had achieved 335 mph (539 km/h) at 16,800 ft (5,120 m) in a clean configuration.[7] The second prototype, R2053, which was furnished with Hercules I-M engines (similar to Hercules II) and was laden with operational equipment, had attained a slower speed of 309 mph at 15,000 ft. According to aviation author Philip Moyes, the performance of the second prototype was considered disappointing, particularly as the Hercules III engines of the initial production aircraft would likely provide little improvement, especially in light of additional operational equipment being installed; it was recognised that demand for the Hercules engine to power other aircraft such as the Short Stirling bomber posed a potential risk to the production rate of the Beaufighter. These factors had thus sparked considerable interest in the adoption of alternative engines for the type.[6]

Roy Fedden, chief designer of the Bristol engine division, was a keen advocate for the improved Hercules VI for the Beaufighter but it was soon passed over in favour of the rival Griffon engine, as the Hercules VI required extensive development.[7] Due to production of the Griffon being reserved for the Fairey Firefly, the Air Ministry instead opted for the Rolls-Royce Merlin to power the Beaufighter until the manufacturing rate of the Hercules could be raised by a new shadow factory in Accrington. The standard Merlin XX-powered aircraft was later called the Beaufighter Mk IIF; the planned slim-fuselage aircraft, alternatively equipped with Hercules IV and Griffon engines, the Beaufighter Mk III and Beaufighter Mk IV respectively, were ultimately left unbuilt.[7]

In February 1940, an order was placed for three Beaufighters, converted to use the alternative Merlin engine. The Merlin engine installations and nacelles were designed by Rolls-Royce as a complete "power egg"; the design and approach of the Beaufighter's Merlin installation was later incorporated into the design for the much larger Avro Lancaster bomber.[8] Success with the Merlin-equipped aircraft was expected to lead to production aircraft in 1941.[8] In June 1940, the first Merlin-powered aircraft conducted its first flight. In late 1940, the two Merlin-equipped prototypes (the third having been destroyed in a bombing raid) were delivered.[9] Flight tests found that the Merlins left the aircraft underpowered, with a pronounced tendency to swing to port, making take-offs and landings difficult and resulting in a high accident rate – out of 337 Merlin-powered aircraft, 102 were lost to accidents.[8][10]

On 2 April 1940, R2052 was delivered to the RAF; it was followed by R2053 two weeks later.[7] On 27 July 1940, the first five production Beaufighters were delivered to the RAF along with another five on 3 August 1940. These production aircraft incorporated aerodynamic improvements, reducing aerodynamic drag from the engine nacelles and tail wheel, the oil coolers were also relocated on the leading edge of the wing.[7] The armament of the Beaufighter had also undergone substantial changes, the initial 60-round capacity spring-loaded drum magazine arrangement being awkward and inconvenient; alternative systems were investigated by Bristol.[11]

Bristol's proposed recoil-operated ammunition feed system was rejected by officials, which led to a new system being devised and tested on the fourth prototype, R2055. The initial rejection was later reversed, upon the introduction of a new electrically-driven feed derived from Châtellerault designs brought to Britain by Free French officers, which was quite similar to Bristol's original proposal.[12] The initial fifty production aircraft were approved for completion with a cannon-only armament. The design of the cannons and the armament configuration was revised on most aircraft. The addition of six .303 Browning machine guns made the Beaufighter the most heavily armed fighter aircraft in the world, capable of delivering a theoretical weight of fire of up to 780 lb (350 kg) per minute; the practical rate of fire was much lower due to gun overheating and ammunition capacity.[12]

Further armament trials and experimental modifications were performed throughout the Beaufighter's operational life. By mid-1941, twenty Beaufighters were reserved for test purposes, including engine development, stability and manoeuvrability improvements and other purposes.[13] In May 1941, the Beaufighter Mk IIs R2274 and R2306, were modified to the Beaufighter Mk III standard; removing the six wing guns and two inboard cannons to install a Boulton-Paul-built four-gun turret behind the pilot, to overcome the effect of recoil and nose-down tendency when firing the usual armament but was found to obstruct the emergency egress of the pilot.[14] The fourth prototype, R2055, had its regular armament replaced by a pair of 40 mm guns for attacking ground targets, the two guns being a Vickers S gun mounted on the starboard fuselage and a Rolls-Royce BH gun mounted on the port fuselage; these trials led to the Vickers gun being installed on an anti-tank Hawker Hurricane IID.[13]

Production

Large orders for the Beaufighter were placed around the outbreak of the Second World War, including one for 918 aircraft shortly after the arrival of the initial production examples.[7] In mid-1940, during an official visit to Bristol's Filton facility by the Minister of Aircraft Production, Lord Beaverbrook, the minister spoke of the importance of the Beaufighter to the war effort and urged its rapid service entry.[7] While the aircraft's size had once caused scepticism, the Beaufighter became the highest performance aircraft capable of carrying the bulky early airborne interception radars used for night fighter operations, without incurring substantial endurance or armament penalties, and was invaluable as a night fighter.[7]

For the maximum rate of production, sub-contracting of the major components was used wherever possible and two large shadow factories to perform final assembly work on the Beaufighter were established via the Ministry of Aircraft Production; the first, operated by the Fairey Aviation Company, was at Stockport, Greater Manchester and the second shadow, run by Bristol, was at Weston-super-Mare, Somerset.[7] Output of the Beaufighter rose rapidly upon the commencement of production.[7]

Through 1940–41, the manufacturing rate of the Beaufighter steadily rose.[10] On 7 December 1940, the 100th Filton-built aircraft was dispatched; the 200th Filton-built aircraft followed on 10 May 1941. On 7 March 1941, the first Fairey-built Beaufighter Mk I performed its first test flight; the first Weston-built aircraft reached the same milestone on 20 February 1941.[10] The volume of production involved, along with other factors, had led to a shortage of Hercules engines being expected, jeopardising the aircraft's manufacturing rate.[7] The next variant, the Beaufighter Mk II, used the Merlin engine instead.[10] On 22 March 1941, the first production Beaufighter Mk II, R2270, conducted its maiden flight; squadron deliveries commenced in late April 1941.[10]

By mid-1941, manufacture of the Beaufighter varied to meet the demands of RAF Fighter Command and RAF Coastal Command.[14] Early aircraft were able to be outfitted and perform with either command but later, the roles and equipment diverged, leading to the production of distinct models, distinguished by the suffixes F for Fighter Command and C for Coastal Command were used.[14] Often, one command opted for modifications and features that the other did not. This occurred with the bellows-type dive brake that became standard for Coastal Command Beaufighters for its usefulness in torpedo-bombing.[15]

Production of the earlier Beaufort in Australia and the great success of British-made Beaufighters by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), contributed to the Australian government deciding in January 1943 to manufacture Beaufighters under the Department of Aircraft Production (DAP) organisation at Fishermans Bend, Melbourne, Victoria from 1944.[16] The DAP Beaufighter was an attack and torpedo bomber known as the "Mark 21". Design changes included Hercules VII or XVIII engines and some minor changes in armament. By September 1945, when British production ended, 5,564 Beaufighters had been built by Bristol and the Fairey Aviation Company at Stockport and RAF Ringway (498); also by the Ministry of Aircraft Production (3336) and Rootes at Blythe Bridge (260). When Australian production ceased in 1946, 364 Mk.21s had been built.[17][18]

Design

The Bristol Beaufighter is a fighter derivative of the Beaufort torpedo-bomber. It is a twin-engine two-seat long range day and night fighter.[19] The aircraft employed an all-metal monocoque construction, comprising three sections with extensive use of 'Z-section' frames and 'L-section' longeron. The wing of the Beaufighter used a mid-wing cantilever all-metal monoplane arrangement, also constructed out of three sections.[19] Structurally, the wing consisted of two spars with single-sheet webs and extruding flanges, completed with a stressed-skin covering, and featured metal-framed ailerons with fabric coverings along with hydraulically-actuated flaps located between the fuselage and the ailerons.[19] Hydraulics were also used to retract the independent units of undercarriage, while the brakes were pneumatically-actuated.[19]

The twin Bristol Taurus engines of the Beaufort, having been deemed insufficiently powerful for a fighter, were replaced by more powerful two-speed supercharger-equipped Bristol Hercules radial engines. These powered three-bladed Rotol constant-speed propellers; both fully feathering metal and wooden blades were used.[19] The extra power had presented vibration issues during development; in the final design, the engines were mounted on longer and more flexible struts, which extended from the front of the wings. This change moved the centre of gravity (CoG) forward, a typically undesirable feature for an aircraft, thus the CoG was moved back to its proper desirable location by shortening the nose, which was possible as the space within the nose had been previously occupied by a bomb aimer, a role that was unnecessary in a fighter aircraft. The majority of the fuselage was positioned aft of the wing and, with the engine cowlings and propellers now further forward than the tip of the nose, gave the Beaufighter a characteristically stubby appearance.[1]

In general, with the exception of the powerplants used, the differences between the preceding Beaufort and Beaufighter were minor. The wings, control surfaces, retractable landing gear and aft section of the fuselage were identical to those of the Beaufort, while the wing centre section was similar apart from certain fittings. The areas for the rear gunner and bomb-aimer were removed, leaving only the pilot in a fighter-type cockpit. The navigator-radar operator sat to the rear under a small Perspex bubble where the Beaufort's dorsal turret had been. Both crew-members had their own hatch in the floor of the aircraft. The front hatch was behind the pilot's seat. As there was no room to climb around the seat-back, the back collapsed to allow the pilot to climb over and into the seat. In an emergency, the pilot could operate a lever that remotely released the hatch, grasp two steel overhead tubes and lift himself out of his seat, swing his legs over the open hatchway, then let go to drop through. Evacuating the aircraft was easier for the navigator, as the rear hatch was in front of him and without obstruction.[20][21]

The Beaufighter's armament was located in various positions on the lower fuselage and wings. The bomb bay of the Beaufort had been entirely omitted, but a small bomb load could be carried externally. A total of four forward-firing 20 mm Hispano Mk III cannons were mounted in the lower fuselage area. These were initially fed from 60-round drums, requiring the radar operator to change the ammunition drums manually—an arduous and unpopular task, especially at night and while chasing a bomber.[11] They were soon replaced by a belt-feed system.[12] The cannons were supplemented by six .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns in the wings (four starboard, two port, the asymmetry caused by the port mounting of the landing light).[22] This was one of the heavier, if not the heaviest, fighter armament of its time.[23][24] When Beaufighters were developed as fighter-torpedo bombers, they used their firepower (often the machine guns were removed) to suppress flak fire and hit enemy ships, especially escorts and small vessels. The recoil of the cannons and machine guns could reduce the speed of the aircraft by around 25 knots.[25]

The Beaufighter was commonly operated as a night fighter, such as during the Battle of Britain. Mass production of the type had coincidentally occurred at almost exactly the same time as the first British airborne interception radar sets were becoming available; the two technologies quickly became a natural match in the night fighter role. As the aircraft's accompaniment of four 20 mm cannons were mounted in the lower fuselage, the vacant nose could accommodate the radar antennas needed, and while early airborne interception equipment was too bulky to fit in single-engine fighters of the day, it could be accommodated in the Beaufighter's spacious fuselage. At night the onboard radar let the aircraft detect enemy aircraft. The heavy fighter remained fast enough to catch up to German bombers and, with its heavy armament, deal out considerable damage to them.[1] While early radar sets suffered from restrictions in range and thus initially limited the aircraft's usefulness, improved radars became available in January 1941, promptly making the Beaufighter one of the more effective night fighters of the era.[10]

Operational service

Introduction

By fighter standards, the Beaufighter Mk.I was rather heavy and slow, with an all-up weight of 16,000 lb (7,000 kg) and a maximum speed of 335 mph (540 km/h) at 16,800 ft (5,000 m). The Beaufighter was the only heavy fighter aircraft available, as the Westland Whirlwind had been cancelled due to production problems with its Rolls-Royce Peregrine engines.[26] On 12 August 1940, the first production Beaufighter was delivered to RAF Tangmere for trials with the Fighter Interception Unit. On 2 September 1940, 25 Squadron, 29 Squadron, 219 Squadron, and 604 Squadron became the first operational squadrons to receive production aircraft, each squadron received one Beaufighter that day to begin converting from their Blenheim IF aircraft.[26][12] The re-equipping and conversion training process took several months to complete; on the night of 17/18 September 1940, Beaufighters of 29 Squadron conducted their first operational night patrol, conducting an uneventful sortie, the first operational daylight sortie was performed on the following day.[27] On 25 October 1940, the first confirmed Beaufighter kill, a Dornier Do 17, occurred.[10]

Initial production deliveries of the Beaufighter lacked the radar for night fighter operations; these were installed by No. 32. MU based at RAF St Athan during late 1940.[10] On the night of 19/20 November 1940, the first kill by a radar-equipped Beaufighter occurred, of a Junkers Ju 88.[10] More advanced radar units were installed in early 1941, which soon allowed the Beaufighter to become effective counter to the night raids of the Luftwaffe. By March 1941, half of the 22 German aircraft claimed by British fighters were by Beaufighters; during the night of 19/20 May 1941, during a raid on London, 24 aircraft were shot down by fighters against two by anti-aircraft ground fire.[10]

In late April 1941, the first two Beaufighter Mk II aircraft, R2277 and R2278, were delivered to 600 and 604 Squadrons; the former squadron being the first to receive the type in quantity in the following month.[28] The Mk II was also supplied to the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy.[14] A night-fighter Beaufighter Mk VIF was supplied to squadrons in March 1942, equipped with AI Mark VIII radar. The Beaufighter showed its merits as a night fighter but went on to perform in other capacities.[1] As the faster de Havilland Mosquito took over as the main night fighter in mid-to-late 1942, the heavier Beaufighter made valuable contributions in other areas such as anti-shipping, ground attack and long-range interdiction, in every major theatre of operations.

On 12 June 1942, a Beaufighter conducted a raid which Moyes said was "perhaps the most impudent of the war".[16] T4800, a Beaufighter Mk 1C of No. 236 Squadron, flew from Thorney Island to occupied Paris at an extremely low altitude in daylight to drop a tricolore on the Arc de Triomphe and strafe the Gestapo headquarters in the Place de la Concorde.[16]

The Beaufighter soon commenced service overseas, where its ruggedness and reliability quickly made the aircraft popular with crews. However, it was heavy on the controls and not easy to fly, with landing being a particular challenge for inexperienced pilots.[29] Due to wartime shortages, some Beaufighters entered operational service without feathering equipment for their propellers. As some models of the twin-engined Beaufighter could not stay aloft on one engine unless the dead propeller was feathered, this deficiency contributed to several operational losses and the deaths of aircrew.[30]

In the Mediterranean, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) 414th, 415th, 416th and 417th night fighter squadrons received a hundred Beaufighters in the summer of 1943, achieving their first victory in July 1943. Through the summer, the squadrons conducted daytime convoy escort and ground-attack operations but primarily flew as night fighters. Although the Northrop P-61 Black Widow fighter began to arrive in December 1944, USAAF Beaufighters continued to fly night operations in Italy and France until late in the war. By the autumn of 1943, the Mosquito was available in enough numbers to replace the Beaufighter as the primary night fighter of the RAF. By the end of the war, some 70 pilots serving with RAF units had become aces while flying Beaufighters. At least one captured Beaufighter was operated by the Luftwaffe – a photograph exists of the aircraft in flight, with German markings.[31]

Coastal Command

It was recognised that RAF Coastal Command required a long-range heavy fighter aircraft such as the Beaufighter and in early 1941, Bristol proceeded with the development of the Beaufighter Mk. IC long-range fighter. Based on the standard Mk I model, the initial batch of 97 Coastal Command Beaufighters were hastily manufactured, making it impossible to incorporate the intended additional wing fuel tanks on the production line and so 50-gallon tanks from the Vickers Wellington were temporarily installed on the floor between the cannon bays.[14]

In April/May 1941, this new variant of the Beaufighter entered squadron service in a detachment from 252 Squadron operating from Malta. This inaugural deployment with the squadron proved to be highly successful, leading to the type being retained in that theatre throughout the remainder of the war.[14] In June 1941, the Beaufighter-equipped 272 Squadron based on Malta claimed the destruction of 49 enemy aircraft and the damaging of 42 more.[16] The Beaufighter was reputedly very effective in the Mediterranean against Axis shipping, aircraft and ground targets; Coastal Command was, at one point, the majority user of the Beaufighter, replacing its inventory of obsolete Beaufort and Blenheim aircraft. To meet demand, both the Fairey and Weston production lines were, at times, only producing Coastal Command Beaufighters.[14]

In 1941, to intensify offensive air operations against Germany and deter the deployment of Luftwaffe forces onto the Eastern Front, Coastal Command Beaufighters began offensive operations over France and Belgium, attacking enemy shipping in European waters.[32] In December 1941, Beaufighters participated in Operation Archery, providing suppressing fire while British Commandos landed on the occupied Norwegian island of Vågsøy. In 1942, long range patrols of the Bay of Biscay were routinely conducted by Beaufighters, intercepting aircraft such as the Ju-88 and Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor operating against Allied anti-submarine patrols.[32] Beaufighters also cooperated with the British Eighth Army during action in the Western Desert Campaign, often in the form of ground strafing.[16]

In mid-1942, Coastal Command began to take delivery of the improved Beaufighter Mk. VIC. By the end of 1942, Mk VICs were being equipped with torpedo-carrying gear for the British 18 in (450 mm) or the US 22.5 in (572 mm) torpedo externally; observers were not happy about carrying the torpedo, as they were unable to use the escape hatch until after the torpedo had been dropped. In April 1943, the first successful torpedo attacks by Beaufighters was performed by 254 Squadron, sinking two merchant ships off Norway.

The Hercules Mk XVII, developing 1,735 hp (1,294 kW) at 500 ft (150 m), was installed in the Mk VIC airframe to produce the TF Mk.X (torpedo fighter), commonly known as the "Torbeau". The Mk X became the main production mark of the Beaufighter. The strike variant of the Torbeau was called the Mk.XIC. Beaufighter TF Xs could make precision attacks on shipping at wave-top height with torpedoes or RP-3 (60 lb) rockets. Early models of the Mk X carried centimetric-wavelength ASV (air-to-surface vessel) radar with "herringbone" antennae on the nose and outer wings, but this was replaced in late 1943 by the centimetric AI Mark VIII radar housed in a "thimble-nose" radome, enabling all-weather and night attacks.

The North Coates Strike Wing of Coastal Command, based at RAF North Coates on the Lincolnshire coast, developed tactics that combined large formations of Beaufighters, using cannons and rockets, to suppress flak, while the Torbeaus attacked at low level with torpedoes. These tactics were put into practice in mid-1943 and in ten months, 29,762 tons (84,226 m3) of shipping were sunk. Tactics were further refined, when shipping was moved from port during the night. The North Coates Strike Wing operated as the largest anti-shipping force of the Second World War, and accounted for over 150,000 tons (424,500 m3) of shipping and 117 vessels for a loss of 120 Beaufighters and 241 aircrew killed or missing. This was half the total tonnage sunk by all strike wings between 1942 and 1945.

Pacific War

.jpg)

The Beaufighter arrived at squadrons in Asia and the Pacific in mid-1942. A British journalist said that Japanese soldiers called it the "whispering death" for its quiet engines, although this is not supported by Japanese sources.[33][1] The Beaufighter's Hercules engines used sleeve valves, which lacked the noisy valve gear common to poppet valve engines. This was most apparent in a reduced noise level at the front of the engine.

In the South-East Asian Theatre, the Beaufighter Mk VIF operated from India as a night fighter and on operations against Japanese lines of communication in Burma and Thailand. Mark X Beaufighters were also flown on long range daylight intruder missions over Burma. The high-speed, low-level attacks were very effective, despite often atrocious weather conditions, and makeshift repair and maintenance facilities.[34]

Southwest Pacific

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was a keen operator of the Beaufighter during the Second World War. On 20 April 1942, the RAAF's first Beaufighter IC (an Australian designation given to various models of the aircraft, including Beaufighter VIC, Beaufighter X, and Beaufighter XIC), which had been imported from Britain, was delivered; the last aircraft was delivered on 20 August 1945.[16] Initial RAAF deliveries were directed to No. 30 Squadron in New Guinea and No. 31 Squadron in North-West Australia.[16]

Before DAP Beaufighters arrived at RAAF units in the South West Pacific Theatre, the Beaufighter Mk IC was commonly employed in anti-shipping missions. The most famous of these was the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, during which Beaufighters were used in a fire-suppression role in a mixed force with USAAF Douglas A-20 Boston and North American B-25 Mitchell bombers.[19] The Beaufighters of No. 30 Squadron flew in at mast height to provide heavy suppressive fire for the waves of attacking bombers. The Japanese convoy, under the impression that they were under torpedo attack, made the tactical error of turning their ships towards the Beaufighters, which allowed the Beaufighters to inflict severe damage on the ships' anti-aircraft guns, bridges and crews during strafing runs with their four 20 mm nose cannons and six wing-mounted .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns. The Japanese ships were left exposed to mast-height bombing and skip bombing attacks by the US medium bombers. Eight transports and four destroyers were sunk for the loss of five aircraft, including one Beaufighter.[25][19]

The role of the Beaufighters during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea was recorded by war correspondent and film-maker Damien Parer, who had flown during the engagement standing behind the pilot of one of the No. 30 Squadron aircraft; the engagement led to the Beaufighter becoming one of the more well-known aircraft in Australian service during the conflict.[25][19] On 2 November 1943, another high-profile event involving the type occurred when a Beaufighter, A19-54, won the second of two unofficial races against an A-20 Boston bomber.[19]

Postwar

From late 1944, RAF Beaufighter units were engaged in the Greek Civil War, finally withdrawing in 1946.

Beaufighters were replaced in some roles by the Bristol Type 164 Brigand, which had been designed using components of the Beaufighter's failed stablemate, the Bristol Buckingham.

The Beaufighter was also used by the air forces of Portugal, Turkey and the Dominican Republic. It was used briefly by the Israeli Air Force after some ex-RAF examples were clandestinely purchased in 1948.

Many Mark 10 aircraft were converted to the target tug role postwar as the TT.10 and served with several RAF support units until 1960. The last flight of a Beaufighter in RAF service was by TT.10 RD761 from RAF Seletar on 12 May 1960.[35]

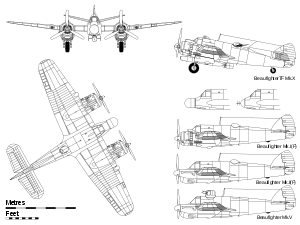

Variants

- Beaufighter Mk IF

- Two-seat night fighter variant

- Beaufighter Mk IC

- The "C" stood for coastal command variant; many were modified to carry bombs

- Beaufighter Mk IIF

- However well the Beaufighter performed, the Short Stirling bomber programme by late 1941 had a higher priority for the Hercules engine, and the Rolls-Royce Merlin XX-powered Mk IIF night fighter was the result

- Beaufighter Mk III/IV

- The Mark III and Mark IV were to be Hercules and Merlin powered Beaufighters with a new, slimmer fuselage, carrying an armament of six cannons and six machine guns that improved performance. The necessary costs of the changes to the production line led to the curtailing of the marks.[36]

- Beaufighter Mk V

- The Vs had a Boulton Paul turret with four 0.303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns mounted aft of the cockpit supplanting one pair of cannons and the wing-mounted machine guns. Only two (Merlin-engined) Mk Vs were built. When tested by the A&AEE, R2274 was capable of 302 mph at 19,000 ft.[37]

- Beaufighter Mk VI

- The Hercules returned with the next major version in 1942, the Mk VI, which was eventually built to over 1,000 examples. Changes included a dihedral tailplane.[38]

- Beaufighter Mk VIC

- Coastal Command version, similar to the Mk IC

- Beaufighter Mk VIF

- Night fighter equipped with AI Mark VIII radar

- Beaufighter Mk VI (ITF)

- Interim torpedo fighter version

- Beaufighter Mk VII

- Proposed Australian-built variant with Hercules 26 engines, not built

- Beaufighter Mk VIII

- Proposed Australian-built variant with Hercules XVII engines, not built

- Beaufighter Mk IX

- proposed Australian-built variant with Hercules XVII engines, not built

- Beaufighter TF Mk X

- Two-seat torpedo fighter aircraft, dubbed the "Torbeau". Hercules XVII engines with cropped superchargers improved low-altitude performance. The last major version (2,231 built) was the Mk X. The later production models featured a dorsal fin.[39]

- Beaufighter Mk XIC

- Coastal Command version of the Mk X, with no torpedo gear

- Beaufighter Mk XII

- Proposed long-range variant of the Mk 11 with drop tanks, not built

- Beaufighter Mk 21

- The Australian-made DAP Beaufighter. Changes included Hercules XVII engines, four 20 mm cannons in the nose, four Browning .50 in (12.7 mm) in the wings and the capacity to carry eight 5 in (130 mm) High Velocity Aircraft Rockets, two 250 lb (110 kg) bombs, two 500 lb (230 kg) bombs and one Mk 13 torpedo.

- Beaufighter TT Mk 10

- After the war, many RAF Beaufighters were converted into target tug aircraft

- Australian experimental prototypes

- Twin Merlin engines;

- 40mm Bofors gun fitted.

Operators

Survivors

Museum display

.jpg)

- Australia

- Beaufighter Mk.XXI A8–186 – Built in Australia in 1945, A8–186 saw service with No. 22 Squadron RAAF at the very end of World War 2. After spending some years on a farm in New South Wales, it was bought in 1965 by the Camden Museum of Aviation, a private aviation museum at Camden Airport, Sydney Australia. It was restored using parts gathered from a wide variety of sources and wears "Beau-gunsville" nose art. (They also have a complete nose section that was found at a Sydney Railway workshops and acquired by the museum; see "Harry's Baby", below.[40]

- Beaufighter Mk.XXI A8–328 – This Australian–built aircraft is displayed at the Australian National Aviation Museum near Melbourne as A8-39/EH-K. Completed on the day the Pacific War ended, it saw post-war service as a target-tug.[41]

- Beaufighter Mk.XXI A8-386 – nose section only, displayed at the Camden Museum of Aviation with "Harry's Baby" nose art.[42]

- United Kingdom

- Beaufighter TF.X, RD253 – Displayed at the Royal Air Force Museum in London, this aircraft flew with the Portuguese Air Force as BF-13 in the late 1940s. It was used as an instructional airframe before its return to the UK in 1965. Restoration was completed in 1968, using components scavenged from a wide variety of sources, including some parts recovered from a crash site.[43]

- Beaufighter TF.X RD220 – This aircraft is currently displayed while under restoration at the National Museum of Flight at East Fortune Airfield, east of Edinburgh. Post-war, it served with the Portuguese naval air arm. After passing through the hands of the Portuguese Museu do Ar and the South African Air Force Museum, it was acquired by National Museums Scotland in 2000.[44]

- United States

- Beaufighter Mk Ic A19-43[45] – On public display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Dayton, Ohio since October 2006. Although flown in combat in the south-west Pacific by 31 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force, A19-43 is painted as T5049, Night Mare, a USAAF Beaufighter flown by Capt. Harold Augspurger, commander of the 415th Night Fighter Squadron, who shot down a Heinkel He 111 carrying German staff officers in September 1944. The Beaufighter was recovered from a dump at Nhill, Australia, in 1971, where it had been abandoned in 1947. It was acquired by the USAF Museum in 1988.[46]

Under restoration/stored

- Beaufighter TF.X RD867 – Under storage at Canada Aviation Museum, RD867 awaits restoration. It is a semi-complete RAF restoration but lacks engines, cowlings or internal components. It was received from the RAF Museum in exchange for a Bristol Bolingbroke in 1969.

- Beaufighter Mk.Ic A19-144 – Owned by The Fighter Collection at Duxford, this aircraft has been undergoing a lengthy restoration to flying status for some years. It is a composite aircraft built using parts from JM135/A19-144 and JL946/A19-148.[47]

A number of sunken aircraft are known; in 2005, the wreck of a Beaufighter (probably a Mk.IC flown by Sgt Donald Frazie and navigator Sgt Sandery of No. 272 Squadron RAF) was identified about 0.5-mile (0.80 km) off the north coast of Malta. The aircraft ditched in March 1943, after an engine failure occurred soon after take-off and lies inverted on the sea bed, in 38 metres (125 ft) of water.[48]

Another Mediterranean wreck lies in 34 metres (112 ft) of water near the Greek island of Paros.[49] This is possibly Beaufighter TF.X LX998 of 603 Squadron, which was shot down after destroying a German Arado Ar 196 during an anti-shipping mission in November 1943. The Australian crew survived and were rescued by a British submarine.

A Mk.VIC Beaufighter, serial A19-130, lies in 204 feet (62 m) of water, just off the coast of Fergusson Island in the western Pacific. It was lost in almost identical circumstances to the Malta aircraft – it ditched in August 1943 after an engine failure soon after takeoff. The aircraft sank within seconds, but both crew and their passenger escaped and swam to shore. The wreck was located in 2000.[50]

In May 2020, the wreck of a Beaufighter TF.X, believed to be JM333 of No. 254 Squadron, was uncovered by shifting sands on Cleethorpes beach near Grimsby. The aircraft was ditched on April 21, 1944 after suffering a double engine failure shortly after takeoff from North Coates. The crew survived uninjured.[51]

The Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England has a Beaufighter cockpit section on public display. Its identity is thought possibly to be T5298.

Specifications (Beaufighter TF Mk.X)

Data from Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II,[52] The Bristol Beaufighter I & II[19]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 41 ft 4 in (12.60 m)

- Wingspan: 57 ft 10 in (17.63 m)

- Height: 15 ft 10 in (4.83 m)

- Wing area: 503 sq ft (46.7 m2) [53]

- Airfoil: root: RAF-28 (18%) ; RAF-28 (10%)[54]

- Empty weight: 15,592 lb (7,072 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 25,400 lb (11,521 kg) with one torpedo

- Fuel capacity: 550 imp gal (660 US gal; 2,500 l) normal internal fuel

- Maximum fuel capacity: 682 imp gal (819 US gal; 3,100 l) (with optional 2x 29 imp gal (35 US gal; 130 l) external tanks / 1x 24 imp gal (29 US gal; 110 l) tank in lieu of port wing guns / 1x 50 imp gal (60 US gal; 230 l) tank in lieu of stbd. wing guns)

- Powerplant: 2 × Bristol Hercules XVII or Bristol Hercules XVIII 14-cylinder air-cooled sleeve-valve radial piston engines, 1,600 hp (1,200 kW) each

- Propellers: 3-bladed constant-speed propellers

Performance

- Maximum speed: 320 mph (510 km/h, 280 kn) at 10,000 ft (3,000 m)

- Range: 1,750 mi (2,820 km, 1,520 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 19,000 ft (5,800 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,600 ft/min (8.1 m/s)

Armament

- Guns: * 4 × 20 mm (0.787 in) Hispano Mk II cannon (240 rpg) in nose

- 1 × manually operated 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning for observer

- Rockets: 8 × RP-3 60 kg (130 lb) rockets

- Bombs: 2× 250 lb (110 kg) bombs or 1× British 18 inch torpedo or 1x Mark 13 torpedo

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Douglas A-20 Havoc

- Douglas A-26 Invader

- de Havilland Mosquito

- Northrop P-61 Black Widow

- Petlyakov Pe-3

- Heinkel He 219

- Kawasaki Ki-45

- I.Ae. 24 Calquin

Related lists

References

Notes

- Moyes 1966, p. 3.

- Moyes 1966, p. 4.

- Buttler 2004, p. 38.

- Moyes 1966, pp. 3–4.

- Buttler 2004, p. 40.

- Moyes 1966, pp. 4–5.

- Moyes 1966, p. 5.

- White 2006, p. 64.

- Moyes 1966, pp. 5, 10.

- Moyes 1966, p. 10.

- Moyes 1966, pp. 5–6.

- Moyes 1966, p. 6.

- Moyes 1966, pp. 5, 11, 13.

- Moyes 1966, p. 11.

- Moyes 1966, pp. 11, 13.

- Moyes 1966, p. 14.

- Franks 2002, p. 171.

- Hall 1995, p. 24.

- Moyes 1966, p. 16.

- White 2006, pp. 62–64.

- Moyes 1966, pp. 5, 16.

- Bristol Beaufighter VI squadron.com Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Bristol Beaufighter – Variants and Stats". History of War. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Its armament was exceeded by the gunship variants of the US North American B-25 Mitchell and Douglas A-26 Invader medium bombers

- Bradley 2010, p. 20.

- Bowyer 2010, p. 262.

- Moyes 1966, p. 7.

- Moyes 1966, pp. 10–11.

- "Bristol Beaufighter". Aviation History. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Bailey 2005, p. 114.

- Roba 2009, p. 140.

- Moyes 1966, p. 13.

- Bowyer 1994, p. 90.

- Browne, Anthony Montague, Long Sunset: Memoirs of Winston Churchill's Last Private Secretary London 1995 Chapter 3 ISBN 0304344788

- Thetford, 1976. p. 144.

- Buttler, Tony. Secret Projects: British Fighters and Bombers 1935–1950 (British Secret Projects 3). Leicester, UK: Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-85780-179-2.

- Buttler 2004, p. 63.

- Franks 2002, pp. 65–67.

- Franks 2002, pp. 70–72.

- {"Beaufighter 156 Mk 21 A8-186." Archived 9 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Camden Museum of Aviation. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "DAP Mark 21 Beaufighter, A8–328." Archived 3 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine Australian National Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "Beaufighter/A8-386." beaufighterregistry. Retrieved: 3 April 2015.

- Simpson, Andrew. "Individual History: Bristol Beaufighter TF Mk.X RD253/BF-13/7931M." Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "Bristol Beaufighter TF.X." Archived 27 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine National Museums Scotland. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "Bristol Beaufighter IC, A19-43 / T5049 / Night Mare, National Museum of the United States Air Force." Air-Britain Photographic Images Collection. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "Bristol Beaufighter Mark Ic Serial Number A19-43." Pacificwrecks.com, 26 July 2011. Retrieved: 28 March 2013.

- "Beaufighter/JM135." warbirdregistry.org. Retrieved: 3 April 2015.

- Trzcinski, Marcin. "On! On!" Archived 28 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Diver, 2005. Retrieved: 3 April 2015.

- "Beaufighter Wreck Paros". Archived 4 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Paros Adventures. Retrieved: 28 March 2013.

- "Bristol Beaufighter Mark VIc Serial Number A19-130". Pacificwrecks.com, 26 July 2011. Retrieved: 27 March 2013.

- "Hidden Wreck of RAF Fighter Emerges from Sands on Cleethorpes Beach". Grimsby Live, 28 May 2020. Retrieved: 1 June 2020.

- Bridgman 1946, pp. 110–111.

- March 1998, p. 57.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Ashworth, Chris. RAF Coastal Command: 1936–1969. London: Patrick Stephens Ltd., 1992. ISBN 1-85260-345-3.

- Bailey, James Richard Abe (Jim). "The Sky Suspended". London: Bloomsbury, 2005. ISBN 0-7475-7773-0.

- Bingham, Victor. Bristol Beaufighter. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, Ltd., 1994. ISBN 1-85310-122-2.

- Bowyer, Chaz. Beaufighter. London: William Kimber, 1987. ISBN 0-7183-0647-3.

- Bowyer, Chaz. Beaufighter at War. London: Ian Allan Ltd., 1994. ISBN 0-7110-0704-7.

- Bowyer, Michael J. F. The Battle of Britain: The Fight for Survival in 1940. Manchester, UK: Crécy Publishing, 2010. ISBN 978-0-85979-147-2.

- Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects — Fighters and Bombers 1935–1950. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-85780-179-2.

- Bridgeman, Leonard, ed. "The Bristol 156 Beaufighter." Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Studio, 1946. ISBN 1-85170-493-0.

- Flintham, V. Air Wars and Aircraft: A Detailed Record of Air Combat, 1945 to the Present. New York: Facts on File, 1990. ISBN 0-8160-2356-5.

- Franks, Richard A. The Bristol Beaufighter, a Comprehensive Guide for the Modeller. Bedford, UK: SAM Publications, 2002. ISBN 0-9533465-5-2.

- Gilman J.D. and J. Clive. KG 200 (novel). London: Pan Books Ltd., 1978. ISBN 978-1-902109-33-6.

- Hall, Alan W. Bristol Beaufighter (Warpaint No. 1). Dunstable, UK: Hall Park Books, 1995.

- Howard. "Bristol Beaufighter: The Inside Story". Scale Aircraft Modelling, Vol. 11, No. 10, July 1989.

- Innes, Davis J. Beaufighters over Burma – 27 Sqn RAF 1942–45. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press, 1985. ISBN 0-7137-1599-5.

- March, Daniel J., ed. British Warplanes of World War II. London: Aerospace Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-874023-92-1.

- Mason, Francis K. Archive: Bristol Beaufighter. Oxford, UK: Container Publications.

- Moyes, Philip J.R. The Bristol Beaufighter I & II (Aircraft in Profile Number 137). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1966.

- Parry, Simon W. Beaufighter Squadrons in Focus. Walton on Thames, Surrey, Uk: Red Kite, 2001. ISBN 0-9538061-2-X.

- Roba, Jean Louis. Foreign Planes in the Service of the Luftwaffe. Pen & Sword Aviation, 2009. ISBN 1-84884-081-0.

- Scutts, Jerry. Bristol Beaufighter (Crowood Aviation Series). Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: The Crowood Press Ltd., 2004. ISBN 1-86126-666-9.

- Scutts, Jerry. Bristol Beaufighter in Action (Aircraft number 153). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-89747-333-7.

- Spencer, Dennis A. Looking Backwards Over Burma: Wartime Recollections of a RAF Beaufighter Navigator. Bognor Regis, West Sussex, UK: Woodfield Publishing Ltd., 2009. ISBN 1-84683-073-7.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918. London: Putnam & Company, 1976. ISBN 978-0-37010-056-2.

- Thomas, Andrew. Beaufighter Aces of World War 2. Botley, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-84176-846-4.

- White, Graham. The Long Road to the Sky: Night Fighter Over Germany. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Casemate Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84415-471-5.

- Wilson, Stewart. Beaufort, Beaufighter and Mosquito in Australian Service. Weston, ACT, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 1990. ISBN 0-9587978-4-6.

Further reading

- Bradley, Phillip. To Salamaua. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-107-27633-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bristol Beaufighter. |

- Austin & Longbridge Aircraft Production

- A picture of a Merlin-engined Beaufighter II

- Bristol Beaufighter further information and pictures

- Beaufighter Squadrons

- "Beaufighter – Whispering Death, The Forgotten Warhorse". You Tube GB. c4nucksens8tion. 16 March 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Torpedo Beaufighter" a 1943 Flight article

- "Whispering Death" a 1945 Flight article on Beaufighters in Burma

- Pilot's Notes