Bo'ness

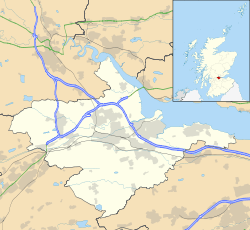

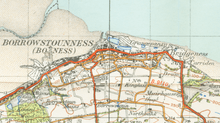

Borrowstounness (commonly known as Bo'ness (/boʊˈnɛs/ boh-NESS)) is a town and former burgh and seaport on the south bank of the Firth of Forth in the Central Lowlands of Scotland. Historically part of the county of West Lothian, it is within the Falkirk council area, 16.9 miles (27.2 km) north-west of Edinburgh and 6.7 miles (10.8 km) east of Falkirk. At the 2011 United Kingdom census, the population of the Bo'ness Locality was 15,100.

| Bo'ness Borrowstouness

| |

|---|---|

A view over the town looking north towards the Firth of Forth | |

Bo'ness Borrowstouness Location within the Falkirk council area | |

| Area | 2.3 sq mi (6.0 km2) |

| Population | 14,490 [1](2008 est.) |

| • Density | 6,300/sq mi (2,400/km2) |

| OS grid reference | NS998816 |

| • Edinburgh | 16.9 mi (27.2 km) |

| • London | 343 mi (552 km) |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BO'NESS |

| Postcode district | EH51 |

| Dialling code | 01506 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

| Website | falkirk.gov.uk |

Toponymy

The name Borrowstoun, from the Old English for "Beornweard's farmstead", refers to a hamlet a short way inland from Borrowstounness. The suffix ness, "headland", serves to differentiate the two.[2] The name was corrupted via association with "burgh",[3] and then eventually contracted to Bo'ness.

The Gaelic name "Ceann Fhàil" is cognate with "Kinneil" still retained as the name of an area in Bo'ness. "Ceann" means head, and "f(h)àil" is a corruption of Latin vallum and reflects the earlier "Penfahel" of Brythonic.

History

Roman

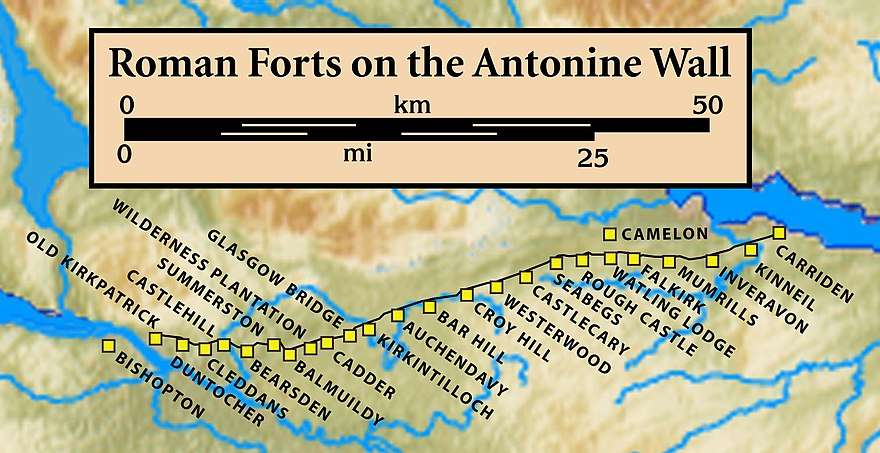

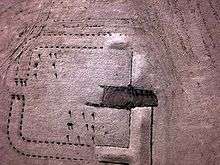

Bo'ness has important historical links to the Roman period and marks the eastern extent of the Antonine Wall which stretched from Bo'ness to Old Kilpatrick on the west coast of Scotland. The Antonine Wall was named as an extension to the Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site by UNESCO in July 2007. A Roman fortlet can still be seen at Kinneil Estate.[5]

Roman artifacts, some with inscriptions, have been found in the eastern part of the town at Carriden. A Roman fort called Veluniate, long since lost to history, once stood on the site now occupied by the grounds of Carriden House. Indeed, it is said that stones from the fort were used in the building of the mansion house.

Several artifacts have been uncovered over the years by the local farming community, including The Bridgeness Slab with many of them now on display in the Museum of Edinburgh or at the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow.[6] A replica was unveiled by Bo'ness Community Council and Falkirk Council on 7 September 2012 in Kinningars Park. A video about its history and manufacture is available online.[7] Other Roman sites have been identified at Muirhouses (known locally as 'The Murrays') and Kinglass on the south-east side of the town.

Kinneil House

Kinneil House is a historic house to the west of Bo'ness now in the care of Historic Scotland. It sits within a public park, which also incorporates a section of the Roman Antonine Wall. In the grounds of Kinneil House is the ruin of the small house where James Watt worked on his steam engine.[8]

Kinneil was mentioned by Bede, who wrote that it was named Pennfahel ('Wall's end') in Pictish and Penneltun in Old English. It was also Pengwawl in old Welsh.

Commerce and Industry

When the town's commissioners bought the land for the town hall and park in the 1890s, the town's prosperity was on the rise. By its completion, the story was not so encouraging. Plans were approved however by the Dean of Guild Court on 14 October 1902. The total cost was made up of £5,000 from Andrew Carnegie for the library, £6,000 borrowed by the council and £1,000 from the Common Good Fund. The stone came from the town's Maidenpark Quarry. Work commenced immediately and was completed on time by 31 March 1904 in time for the opening as part of the Fair Day celebrations in July. As part of the ceremony, a memorial stone was laid beneath which was placed a glass jar containing a copy of The Scotsman The Glasgow Herald, Bo'ness Journal and Linlithgow Gazette, a list of councillors and a copy of the council minutes.[9]

The town was a recognised port from the 16th century; a harbour was authorised by an Act of Parliament in 1707. The harbour, constructed progressively during the 18th century, was extended and complemented by a dry dock in 1881 (works designed by civil engineers Thomas Meik and Patrick Meik).[10] The commercial port (heavily used for the transport of coal and pit props) eventually closed in 1959, badly affected by silting and the gradual downturn of the Scottish coal mining industry. Plans currently exist for the regeneration of the docks area including reopening the port as a marina.[11]

Bo'ness was a site for coal mining from medieval times. Clay mining was carried out on a smaller scale. The shore was the site of industrial salt making, evaporating seawater over coal fires. The ruins of several fisheries (fish storage houses) along the shoreline evidences long gone commercial fishing activity. The town was also home to several sizable potteries,[12] one product being the black 'wally dugs'[13] which sat in pairs over many fireplaces. Metalworking is still carried out, and examples of the Bo'ness Iron Company's work are to be found in many places.[14]

Shipbreaking

In the twentieth century Bo'ness was one of several Scottish ports involved in the shipbreaking industry. The shipbreaking yard was established by the Forth Ship Breaking Company (1902-1920), which was then taken over by P & W Maclellan who continued operating until about 1970.[15] On a high spring tide the ship destined to be broken up would be manoeuvred to the far (north) side of the river and then steamed across with all speed to drive her as far as possible up the beach. A fo’c’stle crew would lower the ship's anchors as soon as she came to rest to stop her sliding back into the river. The bows would come almost up to Bridgeness Road.[16] Amongst the many ships broken up at the yard were:

Present

Bo'ness is now primarily a commuter town, with many of its residents travelling to work in Edinburgh, Glasgow or Falkirk. One of the main local sources of employment is the Ineos petrochemical facility (formerly BP) located in nearby Grangemouth.

Present-day attractions in the town include the Bo'ness & Kinneil Railway and the Birkhill Fireclay Mine. Kinneil House, built by the powerful Hamilton family in the 15th century, lies on the western edge of the town. In the grounds are a cottage where James Watt worked on his experimental steam engine and the steam cylinder of a Newcomen engine. The remains of an engine house are located in Kinningars Park, off Harbour Road.[17]

Bo'ness has a single secondary school, Bo'ness Academy, and five primary schools: Kinneil, Deanburn, Bo'ness Public School, St Mary's, and the Grange School. There are a number of churches, including Bo'ness Old Kirk, Carriden Parish Church, St Andrew's Parish Church, Craigmailen United Free Church, St. Catharine's Episcopal Church, Bo'ness Apostolic Church, Bo'ness Baptist Church, The Bo'ness Salvation Army and St. Mary of the Assumption Roman Catholic Church. On 25 October 2011 it was announced that the Rev Albert Bogle, minister at the town's St Andrew's Church, would be nominated to be Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland for 2012.[18]

As of 2011, consideration is being given to the possible renovation of the town's harbour.

Bo'ness is also home to the recently refurbished Hippodrome Cinema, which is the oldest picture house in Scotland. The building, along with many other buildings in Bo'ness, was designed by Matthew Steele, a local resident and architect. The Hippodrome was built in 1912. Some footage of it survives from 1950 in Bo'ness Children's Fair Festival.[19] The festival continues to this day.[20] Bo'ness also has their own theatre name The Barony Theatre, Bo'ness which was transformed into a theatre during the 20th Century, prior to this it was known as a primary school 'Borowstoun Primary' Annually their band of player's 'The Barony Player's' put on acclaimed plays such as The Steamie, Gregory's Girl, Dad's Army and The Crucible. They also host visiting companies who produce in their venue such as the annual pantomime which is always a sell out success.

Bo'ness was fictionalized as Onderness in a series of contemporary whodunits by EJ Lamprey.

Sport

Bo'ness is home to the football club Bo'ness United, and also to Bo'ness United Ladies and Bo'ness United Under 16s. Bo'ness Academy has a rugby team. Bo'ness RFC has had its first ever rugby club established in September 2011. Bo'ness Cycling Club was reformed in 2010 as Velo Sport Bo'ness. Jim Smellie was a lesser-known local legend, being an 11 times Scottish Cycling Champion, and some of the trophies collected over the years can be viewed at Kinneil House Museum.[21]

Bo'ness has also played an important role in British motorsport. Hillclimb events, including the first ever round of the British Hillclimb Championship and several thereafter,[22] were held on a course on the Kinneil estate most years from 1932 until 1966. Since 2008, an annual Revival event for classic road-going and competition cars has been held on approximately the same course.[23]

Notable people

- George Baird, minister

- John Begg, architect.

- Henry Cadell, geologist.

- George Denholm, Battle of Britain fighter pilot.

- George W. Easton, athlete.

- James Gardiner (British Army officer), redcoat.

- Jo Gibb, actor.

- Christine Grant, University of Iowa.

- James Hamilton, 1st Lord Hamilton

- Margaret Kidd, advocate.

- Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall, children's writer.

- Michael Potter, minister and prisoner on the Bass Rock

- James Brunton Stephens, Australian poet.

- Harcus Strachan, Canadian soldier, and winner of VC.

- William Young (1761–1847), Royal Navy

See also

- Bo'ness Hill Climb

- List of places in Falkirk district

- Antonine Wall

- SS Kinneil

- Charles Clough

References

- Scottish Neighbourhood Statistics Archived 14 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, www.gro-scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 2011-04-30

- Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Mills, A. D.; Room, Adrian (2002). The Oxford Names Companion. Oxford: the University Press. p. 951. ISBN 0198605617.

- Ross, David. Dictionary of Scottish Place-Names. Birlinn. p. 15.

- Macdonald, Sir George (1934). The Roman wall in Scotland, by Sir George Macdonald (2d ed., rev., enl., and in great part rewritten ed.). Oxford: The Clarendon press. pp. 362–365. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- "Historic Scotland - Looking after our heritage - The Antonine Wall".

- "Stone window fragments, Carriden". Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Roman film now online". Kinneil Estate, Bo'ness. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Old Bo'ness by Alex F. Young ISBN 978-1-84033-482-1

- Young, Alex F. (2009). Old Bo'ness. Catrine, Ayrshire: Stenlake Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9781840334821.

- Old Bo'ness by Alex F. Young, ISBN 978-1-84033-482-1

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 September 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jardine, Robert. "Bo'ness Pottery". Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- "Wemyss Ware". Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- "Ballantines Castings Ltd". Archived from the original on 18 March 2012.

- The Shipbreaking Industry by Frank C. Bowen, c 1930's.

- Bo'ness Waterfront Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Forth Yacht Clubs Association.

- "Bridgeness, Kinningars Park Dovecot Including Wall and Capped Pit Shaft, Grangepans". Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- "Charity founder to be next Church of Scotland moderator". BBC News. 25 October 2011.

- "Bo'ness Children's Fair Festival". Moving Image Archive. Templar Film Studios. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- "History of The Fair". Bo'ness Children's Fair Festival. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- Smillie, Derek. "Bo'ness Cycling Legend". s1 Bo'ness. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- https://hillclimb.uk/venue/boness/

- http://www.bonessrevival.co.uk/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bo'ness. |

- Bo'ness web site

- Proposals by ING to transform harbor area

- Website on the historical Kinneil Estate, at the western edge of Bo'ness

- Bo'ness Pottery - The Pottery Industry of Borrowstounness 1766 - 1958

- Oblique aerial view of Bo'Ness Ship Breakers Yard. RCAHMS

- National Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE (selection of archive films about Bo’ness)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.