Muscle cuirass

In classical antiquity, the muscle cuirass (Latin: lorica musculata)[1], anatomical cuirass, or heroic cuirass is a type of cuirass made to fit the wearer's torso and designed to mimic an idealized male human physique. It first appears in late Archaic Greece and became widespread throughout the 5th and 4th centuries BC.[2] Originally made from hammered bronze plate, boiled leather also came to be used. It is commonly depicted in Greek and Roman art, where it is worn by generals, emperors, and deities during periods when soldiers used other types.

In Roman sculpture, the muscle cuirass is often highly ornamented with mythological scenes. Archaeological finds of relatively unadorned cuirasses, as well as their depiction by artists in military scenes, indicate that simpler versions were worn in combat situations. The anatomy of muscle cuirasses intended for use might be either realistic or reduced to an abstract design; the fantastically illustrated cuirasses worn by gods and emperors in Roman statues usually incorporate realistic nipples and the navel within the scene depicted.

Use

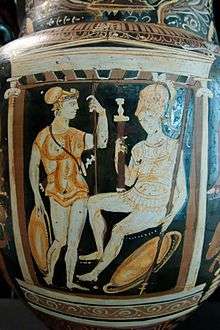

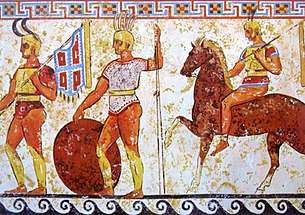

The cuirasses were cast in two pieces, the front and the back, then hammered. They were a development from the early Archaic bell-shaped cuirass, weighing about 25 pounds.[4] Examples from the 5th century BC have been found in the tombs of Thracians, whose cavalrymen wore them.[5] The earliest surviving depiction in Greek sculpture seems to be an example on a sculptural warrior's torso found on the acropolis of Athens and dating around 470 – 460 BC. The muscle cuirass is also depicted on Attic red-figure pottery, which dates from around 530 BC and into the late 3rd century BC.

From around 475 to 450 BC, the muscle cuirass was shorter, covering less of the abdomen, and more nipped at the waist than in later examples. It was worn over a chitoniskos. In neo-Attic art, the muscle cuirass was worn over a longer chiton.[6] Tomb II at Vergina contained an iron muscle cuirass that was decorated with embossed gold.[7]

The Italian muscle cuirass lacked the shoulder-guards found on Greek examples.[8] Examples among the Samnites and Oscans sketch a blockier torso more roughly than the anatomically realistic Greek pieces.[9] Many examples come from graves in Campania,[10] Etruria, and elsewhere in southern Italy.[3]

Polybius omits the muscle cuirass in his description of the types of armor worn by the Roman army, but archaeological finds and artistic depictions suggest that it was worn in combat. The monument of Aemilius Paulus at Delphi shows two Roman infantrymen wearing mail shirts alongside three who wear muscle cuirasses.[11] They were worn mostly by officers, and may have been molded leather as well as metal, with fringed leather (Pteryges) at the armholes and lower edge.[12] The muscle cuirass is one of the elements that distinguished a senior officer's "uniform".[13]

Artistic qualities

Cuirasse esthétique

The sculptural replicating of the human body in the muscle cuirass may be inspired by the concept of heroic nudity, and the development of the muscle cuirass has been linked to the idealized portraiture of the male body in Greek art.[14] Kenneth Clark attributes the development of an idealized standard musculature, varied from the facts of nature, to Polykleitos:

Polykleitos set himself to perfect the internal structure of the torso. He recognized that it allowed for the creation of a sculptural unit in which the position of humps and hollows evokes some memory and yet can be made harmonious by variation and emphasis. There is the beginning of such a system in the torso from Miletos and that of the Kritios youth; but Polykleitos' control of muscle architecture was evidently far more rigorous, and from him derives that standard schematization of the torso known in French as the cuirasse esthétique, a disposition of muscles so formalized that it was in fact used in the design of armor and became for the heroic body like the masks of the antique stage. The cuirasse esthétique, which so greatly delighted the artists of the Renaissance, is one of the features of antique art that have done most to alienate modern taste.... But... we can see from certain replicas that this was originally a construction of great power. Such is the copy of the Doryphoros in the Uffizi.[15]

Decoration

Hellenistic rulers added divine emblems, such as thunderbolts, to the pteruges.

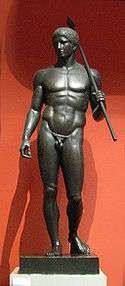

Another conventional decoration is the gorgoneion, or Medusa's head, on the upper chest, and often vegetative motifs on the pectorals.[16] One of the elements of iconography that identify the Greek Athena and the Roman Minerva, goddesses who embodied the strategic side of warfare, was a breastplate bearing a gorgoneion (see Aegis). Other deities, particularly the war gods Ares and Mars, could be portrayed with muscle cuirasses.[6]

Roman emperors

Among freestanding sculptures portraying Roman emperors, a common type shows the emperor wearing a highly ornamented muscle cuirass, often with a scene from mythology. Figures such as winged victories, enemies in defeat, and virtues personified represent the emperor as master of the world. Symbolic arrangements this elaborate never appear on Greek cuirasses.[17]

The cuirass on the famous Augustus of Prima Porta is particularly ornate. In the center, a Roman officer is about to receive a Roman military standard (aquila) from a bearded "barbarian" who appears to be a Parthian. The Roman, who has a hound at his side, is most often identified as a young Tiberius, and the scene is usually read as the return in 20 BC of the standards lost at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC. The anatomically realistic navel (Greek omphalos, Latin umbilicus) is placed between the two central figures, slightly below ground level in relation to the feet and centered above the personification of Earth, positioned over the abdomen.[18] Her reclining position, cornucopia, and the presence of suckling babies is common to other goddesses in Augustan art who represent peace and prosperity. Other figures include a lyre-playing Apollo riding a griffin, Diana on the back of a hind, and the quadriga of the Sun at the top.[19]

Gallery

Early Greek cuirass in bronze, 620–580 BC

Early Greek cuirass in bronze, 620–580 BC Two Samnite muscle cuirasses (left and right only), 4th century BC

Two Samnite muscle cuirasses (left and right only), 4th century BC- Greek bronze muscle cuirass, 370–340 BC

Mars wearing muscle cuirass, 1st century AD

Mars wearing muscle cuirass, 1st century AD From a statue of Trajan, 2nd century AD

From a statue of Trajan, 2nd century AD- Indian steel cuirass, 17th to 18th century.

- Japanese Nio do.

References

- Also found as "muscled cuirass" or "lorica musculata". The contemporary Latin phrase lorica musculata appears not to be used among scholars, but will be found at reenactment websites. The word musculatus (nor any verb from which it might derive) does not exist in Classical Latin, according to the Oxford Latin Dictionary, nor in late antiquity, according to the Latin Dictionary of Lewis and Short, which includes patristic writers of the early Christian era.

- M. Treister, "The Theme of Amazonomachy in Late Classical Toreutics: On the Phalerae from Bolshaya Bliznitsa," in Pontus and the Outside World: Studies in Black Sea History, Historiography, and Archaeology (Brill, 2004), p. 205; Charlotte R. Long, The Twelve Gods of Greece and Rome (Brill, 1987), p. 184.

- Treister, "The Theme of Amazonomachy," p. 205.

- Mikhail Y. Treister, Hammering Techniques in Greek and Roman Jewellery and Toreutics (Brill, 2001), pp. 115–118; Richard A. Gabriel and Karen S. Metz, From Sumer to Rome: The Military Capabilities of Ancient Armies (Greenwood, 1991), p. 52.

- Treister, Hammering Techniques, p. 115.

- Long, The Twelve Gods, p. 184.

- Treister, Hammering Techniques, p. 118.

- Nicholas Sekunda, Republican Roman Army 200–104 BC (Osprey Publishing, 1996), p. 46.

- Nic Fields, Roman Battle Tactics 390–110 BC (Osprey Publishing, 2010), p. 7 with images.

- Sekunda, Republican Roman Army 200–104 BC, p. 8.

- Sekunda, Republican Roman Army 200–104 BC, pp. 8 and 46.

- Pat Southern, The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 157.

- Hugh Elton, "Military Forces," in The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare (Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 62.

- Jason König, Athletics and Literature in the Roman Empire (Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 103, providing further references in note 27.

- Kenneth Clark, The Nude, Ch. 2, "Apollo."

- Elfriede R. Knauer, "Knemides in the East? Some Observations on the Impact of Greek Body Armor on 'Barbarian' Tribes," in Nomodeiktes: Greek Studies in Honor of Martin Ostwald (University of Michigan Press, 1993), pp. 238–239.

- Knauer in Nomodeiktes p. 239.

- Lawrence Keppie, The Making of the Roman Army: From Republic to Empire (University of Oklahoma Press, 1984), p. 230.

- Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (University of Michigan Press, 1988, 1990), pp. 175, 189–190.

External links

![]()