Greenwich armour

Greenwich armour is the plate armour in a distinctively English style produced by the Royal Almain Armoury founded by Henry VIII in 1511 in Greenwich near London, which continued until the English Civil War. The armoury was formed by imported master armourers hired by Henry VIII, initially including some from Italy and Flanders, as well as the Germans who dominated during most of the 16th century. The most notable head armourer of the Greenwich workshop was Jacob Halder, who was master workman of the armoury from 1576 to 1607. This was the peak period of the armoury's production and it coincided with the elaborately gilded and sometimes coloured decorated styles of late Tudor England.

%2C_Third_Earl_of_Cumberland_MET_DP295743.jpg)

As the use of full plate in actual combat had declined by the late 16th century, the Greenwich armours were primarily created not for battle but for the tournament. Jousting was a favourite pastime of Henry VIII (at dire cost to his health), and his daughter Elizabeth I made her Accession Day tilts a highlight of the court's calendar, focused on hyperbolic declarations of loyalty and devotion in the style of contemporary verse epics. Even late in her reign, courtiers gained favour by participating and dressing the part.

The workshop produced bespoke armour for the nobility; relatively mass-produced government orders for the military mainly went elsewhere. The book of Greenwich armour designs for 24 different gentlemen, known as the "Jacob Album" after its creator, includes many of the most important figures of the Elizabethan court. In this period a distinctive Greenwich style developed, marked by imitating aspects of fashionable clothing styles, and extensive use of gilded and coloured areas, using complex decoration in Northern Mannerist styles.

By the time of the mid-17th century, plate armour had adopted a stark and utilitarian form favoring thickness and protection (from the ever-more-powerful firearms which were redefining battle) over aesthetics and was generally only used by heavy cavalry; afterwards, it was to disappear more or less completely. Therefore, the Greenwich workshop represented the last flourishing of decorative armour-making in England, and comprises a unique genre of late-Renaissance art in its own right.

Characteristics

Henrician Period

Although there were certainly English armourers at work before 1511, indeed they had their own guild in London, it seems that they were both unable to cope with large volume orders, and not able to produce work of the finest quality, and in the latest styles, found in Europe. A payment to Milanese armourers at Greenwich, of £6 2/3 and two hogsheads of wine was made in July 1511; they were under contract for two years from March 1511, and other payments record the setting-up of a mill and the purchase of tools. Greenwich Palace was still an important royal residence, the birthplace of both Henry and his two daughters. By 1515 there were six German master armourers, with (perhaps working separately from) two apparently Flemish masters, two polishers and an apprentice, all working under the English King's Armourer, John Blewbury, and a "Clerk of the Stable". All were given damask livery clothes.[1]

In 1516 the workshop moved closer to London (but still outside the city itself, where guild regulation might have been an issue) to a mill in Southwark, while construction of a new mill at Greenwich began. On completion of this in 1520 they returned to Greenwich.[2]

The first Greenwich harnesses, created under Henry VIII, were typically of uniform colouration, either gilded or silvered all over and then etched with intricate motifs, often designed by Hans Holbein. The lines of these armours were typically not much different from Northern German designs of the same time period; the decorations, though, were often more extravagant. A good example of this early sort of Greenwich style is the harness which is thought to have belonged to Galiot de Genouillac, Constable of France, but was initially created for King Henry. The armour, currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, has a specially designed corset built into the cuirass to support the weight of the burly king's large stomach. This harness also has very wide sabatons in the Maximilian style. Very similar in design, but ungilded, is another tournament harness made for Henry VIII which now resides at the Tower of London and which is famous for its large codpiece.

Golden Age

After the reign of Henry VIII, the Greenwich armour began to evolve into a different and unique style. There were several defining characteristics of this second wave of armour. One was the mimicking of popular fashions of the time in the styles of the armour to reflect the individual wearer's taste in civilian clothing. From 1560 cuirasses were designed to imitate the curving "peascod" style of doublet which was immensely popular among gentlemen during the reign of Elizabeth. This type of cuirass curved outwards in front at a steep angle which culminated at the groin, where it tapered into a small horn-like protrusion. All-over gilding or silvering was replaced by strips of blued or gilded steel, typically running horizontally across the pauldrons at the edge of each lame, and vertically down the cuirass and tassets, which emulated the strips of colourful embroidered cloth that were popular in civilian fashion.

Some armours were provided with an extra pair of tassets for use at the barriers which were very wide, not unlike the form of a pair of trunkhose. The extant armours of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and that of Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke currently display these tassets. The armour of William Somerset, 3rd Earl of Worcester is also similarly styled.

Another defining characteristic of Elizabethan-era Greenwich armour is the extravagant use of colour in general to decorate the steel. Older styles of armour-making, such as Maximilian and Gothic, emphasized the shaping of the metal itself, such as fluting and roping, to create artistic designs in the armour, rather than using colour. The Greenwich style, however, came at a time when complicated decoration of the metal with colour, texture and embossed designs was fashionable across Europe.

Greenwich did not produce the highly modelled figurative designs of some Continental centres, but specialised in bold designs using different colours to form vibrant, striking patterns. Colour contrast became extremely important, as it was in civilian fashion. The extent to which a suit of armour was decorated depended on the wealth of the buyer, and ranged from wildly elaborate and artistic pieces such as George Clifford's famous gilded garniture to relatively simple harnesses of "white armour" overlaid with intersecting patterns of darker-coloured strips. In either case, the use of contrasting colours became a hallmark of the Greenwich style.

There were three main ways in which the steel of the armour was coloured: bluing, browning, and russeting. Bluing the steel gave it a deep, brilliant blue-black finish. Browning, as the name would suggest, coloured the steel a dark brown, which contrasted vividly with gilding as in the harness of George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland. Finally, russeting imparted a dark-red or purple hue to the steel, which was also typically used in conjunction with gilding. All of these base colours would be applied uniformly to the steel of the armour, and then strips of differently coloured steel would be laid across to create patterns, or etched sections of the armour would be gilded. The Earl of Worcester's armour is one striking example of a scalloped design which was originally gilded over dark blued steel.

The Greenwich helmet for the field and tilt has a distinctive form. The typical Greenwich helm is an armet with a very high visor perforated on one or both sides by vertical slits, in the case of a field visor, or with small round holes in the case of a visor for the tilt (most Greenwich armours came with both types.) The rim of the upper bevor juts out forward gracefully, giving the helmet a characteristic "ship's prow" appearance. It also typically has a high raised comb from the rear of the skull extending up to the top of the visor, a feature influenced by the French style.

Finally, Greenwich armours were often made in the form of a garniture, which meant a large set of interchangeable armour pieces, referred to as pieces of exchange, with the same design which could be arranged to form a suit for either mounted combat such as jousting, or combat on foot in the tournament. A garniture would typically include a full plate harness plus an extra visor specially meant for tilting; a burgonet helmet which would be worn open-faced for a parade or ceremony, or with a removable "falling-buffe" visor for combat; a grandguard, which would reinforce the upper portion of the torso and neck for jousting; a passguard, which would reinforce the arm; and a manifer, a large gauntlet to protect the hand. It might also include a shaffron, which would cover the head of the knight's horse, and a set of decorated saddle steels.

Stuart Period

The Greenwich workshop continued producing armours into the reign of James I and Charles I, although the heyday of grand tournaments and exaggerated chivalric pageantry which characterized Elizabethan England had largely passed after the death of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales. This transition can be seen in the styling of the post-Jacobean Greenwich armour; gilded decoration and etching is now absent, and the steel is no longer russeted, polished "white" or boldly colored in any other way but is uniformly a simple blue-gray shade.

Tassets are now frequently knee-length, in the cuirassier fashion. Also, in keeping with innovations in the field of armouring, the inner elbows are often fully protected by articulated lames. Nevertheless, the Greenwich armours even into the period of the English Civil War retained some of the distinctive touches of the last century; the breastplates were still shaped in the peascod fashion and the pauldrons had the same graceful and rounded curves (while those of Continental armours tended towards square shapes). The "ship's prow" form of the close helmet also remained, and can be seen in many portraits of important military figures from the English Civil War.

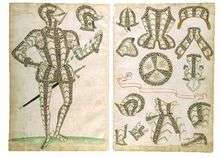

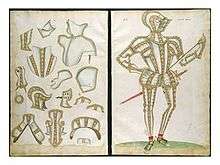

The Jacob Album

An album, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, was drawn up by Jacob Halder which contains full-colour illustrations of twenty-nine different Greenwich armours for various Elizabethan gentlemen of high rank; many of the armours are part of large garnitures with the additional pieces of exchange also depicted. The album displays a picture of each customer standing in the same stylized pose, with right hand on hip and left hand holding a staff of office, and wearing the armour which was to be furnished for him.

The wearers listed in the album include some of the most illustrious and powerful nobles of Elizabeth's court. Among them are Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester; William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke, Sir Thomas Bromley, Lord Chancellor of England; Sir Christopher Hatton, who succeeded Bromley as Lord Chancellor and was also rumored to be Queen Elizabeth's lover; Sir Henry Lee, Queen Elizabeth's first official jousting champion; and George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, the Queen's second official champion and also an important naval commander who briefly captured Fort San Felipe del Morro.

Other notable figures whose suits of armour are displayed in the album are Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset (then "Lord Buckhurst", which survives in the Wallace Collection in London), who served as Lord High Treasurer but is perhaps best known as the co-author of Gorboduc, one of the first tragedies written in blank verse, and Sir James Scudamore, a gentleman usher and tilting champion who was the basis for the character "Sir Scudamour" in The Fairie Queene by Edmund Spenser. One of the armours in the album is labeled as being for "John, Duke of Finland" – the future king John III of Sweden, who visited England in 1560 to promote a marriage between Queen Elizabeth and his brother Eric.

Another design is for a man named Bale Desena, the identity of whom remains a mystery to this day. This man was likely not an Englishman, as his name (which is probably misspelled in the album) suggests Spanish or Italian origin. It is unknown how he commissioned a Greenwich armour, though these armours were sometimes given to foreigners as gifts. Christian of Brunswick, cousin and friend to Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, was given a beautiful gilded Greenwich armour which remained in the family of the Dukes of Brunswick before ultimately being purchased by Ronald Lauder.

Twenty-three of the twenty-nine armours in the album all belong to different individuals; Robert Dudley, Christopher Hatton and Henry Lee, probably owing to their status as favourites to Queen Elizabeth, all had two suits of armour each, in addition to large garnitures with many extra pieces. Several of the armours depicted in this album survive to the present day. The armours of Robert Dudley, William Somerset, and William Herbert are all at the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London, and Christopher Hatton's armour is at the Royal Armouries gallery in Leeds, along with the half-harness (the only one in the album) of a notable soldier, tactician and military writer of the Elizabethan era named John Smythe. The complete garniture of George Clifford is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, along with the armours of Sir James Scudamore and Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke.[3]

When compared with extant examples of the armour to which they correspond, the drawings in Jacob Halder's album are nearly exact representations of the designs of the finished product. There is only one major difference, which is that the drawing for the armour of William Somerset, Earl of Worcester, shows a deep red russeted background with scalloped and gilded bands over it, whereas the portrait of the Earl clearly shows a black background. Other than that, the design matches the armour perfectly, including even the maille shoes. Several of the garnitures in the album feature an identical design – a series of gilt bands in a snaking S-shape pattern overlaid with interlacing diagonal lines in an X pattern, sometimes described as representing lightning, over a background of deeply russeted steel of a purplish colour.

The garnitures with this design are those belonging to Sir James Scudamore, William Compton, 1st Earl of Northampton, and Thomas Sackville. However, comparison with surviving pieces shows that some details of the construction, such as the number of lames in a piece, are often different from the finished work – perhaps suggesting that the makers of the basic pieces were more free or ready to improve on designs as they worked than those working on the decoration.[4]

Gallery

- The same armour of William Somerset as it originally appeared

- Armour of Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset, Jacob Halder, c. 1587 - 1589

- Fauld and tassets of the Sackville armour

Greenwich armour of Sir James Scudamore, 1590s. Jousting was crucial to Scudamore's reputation at court.[5]

Greenwich armour of Sir James Scudamore, 1590s. Jousting was crucial to Scudamore's reputation at court.[5] Armour of Sir John Smythe, soldier and writer, in the Jacob Album

Armour of Sir John Smythe, soldier and writer, in the Jacob Album Surviving armour of Sir John Smythe, nearly identical to its pattern

Surviving armour of Sir John Smythe, nearly identical to its pattern George Clifford wearing the armour shown at top

George Clifford wearing the armour shown at top

Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh

John Farnham

John Farnham

William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke

William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke

Sir Kenelm Digby

Sir Kenelm Digby

Notes

- Richardson, 1–2

- Richardson, 2

- Dean, 128–130 on the Scudamore armour

- Dean, 58–59, 63–68

- The armet shown was made by restorer Daniel Tachaux in 1915 to replace the missing original, and faithfully reproduces the style's distinctive high visor.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greenwich armour. |

- European Weapons and Armor. From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution Ewart Oakeshott, F.S.A ISBN 0-85115-789-0

- Tudor Knight Christopher Gravett and Graham Turner, ISBN 978-1-84176-970-7

- The Archaeological Journal (Volume v. 52) – The Royal Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1895

- Notes on arms and armor, Bashford Dean, 1916, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, available online as PDF from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- "The Royal Armour Workshops at Greenwich", by Thom Richardson, online as PDF from the Royal Armouries.