Boiled egg

Boiled eggs are eggs, typically from a chicken, cooked with their shells unbroken, usually by immersion in boiling water. Hard-boiled eggs are cooked so that the egg white and egg yolk both solidify, while soft-boiled eggs may leave the yolk, and sometimes the white, at least partially liquid and raw. Boiled eggs are a popular breakfast food around the world.

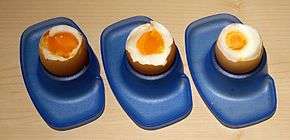

A soft-boiled egg served in the half shell | |||||||

| Main ingredients | Eggs (typically chicken) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variations | Baked eggs, starting temperature, preparation | ||||||

| 136 kcal (569 kJ) | |||||||

| |||||||

Besides a boiling water immersion, there are a few different methods to make boiled eggs. Eggs can also be cooked below the boiling temperature, i.e. coddling, or they can be steamed. The egg timer was named for commonly being used to time the boiling of eggs.

Variations

There are variations both in degree of cooking and in the method of how eggs are boiled, and a variety of kitchen gadgets for eggs exist. These variations include:

- Serving temperature

- Room temperature (for more even cooking and to prevent cracking) or from a refrigerator; eggs may be left out overnight to come to room temperature.

- Piercing

- Some pierce the eggs beforehand with an egg piercer to prevent cracking. There is much debate on this subject. Ekelund et al. in Why eggs should not be pierced claimed that pricking caused egg white proteins to be damaged and was therefore to be discouraged. Others, including the American Egg Board, recommend against this, as it can introduce bacteria and create hairline cracks in the shell through which bacteria can enter the egg.[note 1]

- Vinegar

- Some add vinegar to the water (as is sometimes done with poached eggs) to prevent the white from billowing in case of cracking. For this purpose, table salt can also be used.

- Placing in water

- There are various ways to place the eggs in the boiling water and remove: one may place the eggs in the pan prior to heating, lower them in on a spoon, or use a specialized cradle to lower them in. A cradle is also advocated as reducing cracking, since the eggs do not then roll around loose. To remove, one may allow the water to cool, pour off the boiling water, or remove the cradle.

- Steaming

- Eggs can be taken straight from the refrigerator and placed in the steamer at full steam. The eggs will not crack due to sudden change in temperatures. At full steam, "soft-boiled" eggs can be ready in about 6 minutes and "hard-boiled" eggs in about twice that time. However due to variations in the starting temperature and the size of the egg as well as the altitude of the location (longer needed for higher altitudes), these times can only be an approximation.[1]

- Sous vide

- Rather than cooking in boiling water, boiled eggs can be made by cooking/coddling in their shell "sous vide" in hot water at steady temperatures anywhere from 60 to 85 °C (140 to 185 °F). It turns out that the outer egg white cooks at 75 °C (167 °F) and the yolk and the rest of the white sets from 60 to 65 °C (140 to 149 °F).[2][3]

- Cooking times

- There is substantial variation, with cooking time being the primary variable affecting doneness (soft-boiled vs. hard-boiled). It usually varies from 10–17 minutes for large hard-boiled eggs, 1–4 minutes for large soft-cooked eggs. Depending on altitude above sea level and humidity densities in a given climate, one may require extended amounts of time to reach the soft-boiled stage, and in fact, may never reach a fully hard stage.

- Cooking temperatures

- In addition to cooking at a rolling boil (at 100 °C (212 °F)), one may instead add the egg before a boil is reached, remove water from heat after a boil is reached, or attempt to maintain a temperature below boiling, the latter all variants of coddling.

- Cooling

- After eggs are removed from heat, some cooking continues to occur, particularly of the yolk, due to residual heat, a phenomenon called carry over cooking, also seen in roast meat. For this reason some allow eggs to cool in air or plunge them into cold water as the final stage of preparation. If time is limited, adding a few cubes of ice will quickly reduce the temperature for easy handling.

- Service

- Boiled eggs may be served loose, in an eggcup, in an indentation in a plate (particularly a presentation platter of deviled eggs), cut with a knife widthwise, cut lengthwise, cut with a knife or tapped open with a spoon at either end, or peeled (and optionally sliced, particularly if hard-boiled, either manually or with an egg slicer).

- Baked eggs

- Baking eggs in an oven instead of boiling in water. Baked eggs (350 °F (177 °C) for 1/2 hour in a muffin tin, cool in ice water) are identical to boiled eggs but the shells peel more easily.

Soft-boiled eggs

Chef Heston Blumenthal, after "relentless trials", published a recipe for "the perfect boiled egg" suggesting cooking the egg in water that starts cold and covers the egg by no more than a millimeter, removing the pan from the heat as soon as the water starts to bubble. After six minutes, the egg will be ready.[4]

Soft-boiled eggs are not recommended for people who may be susceptible to salmonella, such as very young children, the elderly, and those with weakened immune systems.[5] To avoid the issue of salmonella, eggs can be pasteurised in shell at 57 °C for an hour and 15 minutes. The eggs can then be soft-boiled as normal.[6]

Soft-boiled eggs are commonly served in egg cups, where the top of the egg is cut off with a knife, spoon, spring-loaded egg topper, or egg scissors, using a teaspoon to scoop the egg out. Other methods include breaking the eggshell by tapping gently around the top of the shell with a spoon.[7] Soft-boiled eggs can be eaten with toast cut into strips, which are then dipped into the runny yolk. In the United Kingdom and Australia, these strips of toast are known as "soldiers".[8]

In Southeast Asia, a variation of soft-boiled eggs known as half-boiled eggs are commonly eaten at breakfast. The major difference is that, instead of the egg being served in an egg cup, it is cracked into a bowl to which dark or light soy sauce or pepper are added. The egg is also cooked for a shorter period of time resulting in a runnier egg instead of the usual gelatin state and is commonly eaten with Kaya toast.

Boiled eggs are also an ingredient in various Philippine dishes, such as embutido, pancit, relleno, galantina, and many others.

In Japan, soft-boiled eggs are commonly served alongside ramen. The eggs are typically steeped in a mixture of soy sauce, mirin, and water after being boiled and peeled. This provides the egg a brownish color that would otherwise be absent from boiling and peeling the eggs alone. Once the eggs have finished steeping, they are served either in the soup or on the side.

Hard-boiled eggs

Hard-boiled eggs are boiled long enough for the yolk to solidify.[9] They can be eaten warm or cold. Hard-boiled eggs are the basis for many dishes, such as egg salad, cobb salad and Scotch eggs, and may be further prepared as deviled eggs.

There are several theories as to the proper technique of hard-boiling an egg. One method is to bring water to a boil and cook for ten minutes.[10] Another method is to bring the water to a boil, but then remove the pan from the heat and allow eggs to cook in the gradually cooling water.[9][11] Over-cooking eggs will typically result in a thin green iron(II) sulfide coating on the yolk.[12] This reaction occurs more rapidly in older eggs as the whites are more alkaline.[13] Immersing the egg in cold water after boiling is a common method of halting the cooking process to prevent this effect.[11] It also causes a slight shrinking of the contents of the egg.

Hard-boiled eggs should be used within two hours if kept at room temperature or can be used for a week if kept refrigerated and in the shell.[14][15][16][17]

Hard-boiled eggs are commonly sliced, particularly for use in sandwiches. For this purpose specialized egg slicers exist, to ease slicing and yield even slices. For consistent slice sizes in food service, several eggs may have their yolk and white separated and poured into a cylindrical mold for stepwise hard-boiling, to produce what is known as a "long egg" or an "egg loaf". Commercial long eggs are produced in Denmark by its inventor Danæg and in Japan by KENKO Mayonnaise. The machine for producing long eggs was first introduced in 1974.[18] In addition to being sliced, long eggs can also be used in their entirety in gala pies.[19]

Peeling

Boiled eggs can vary widely in how easy it is to peel away the shells. In general, the fresher an egg before boiling, the more difficult it is to separate the shell cleanly from the egg white.[20] As a fresh egg ages, it gradually loses both moisture and carbon dioxide through pores in the shell; as a consequence, the contents of the egg shrink and the pH of the albumen becomes more basic. Albumen with higher pH (more basic) is less likely to stick to the egg shell, while pockets of air develop in eggs that have lost significant amounts of moisture, also making eggs easier to peel. Keeping the cooked eggs soaked in water helps keep the membrane under the egg shell moisturized for easy peeling. Peeling the egg under cold running water is an effective method of removing the shell. Starting the cooking in hot water also makes the egg easier to peel.[20] It is often claimed that steaming eggs in a pressure cooker makes them easier to peel.[21] However, double blind testing has failed to show any advantage of pressure cooking over steaming, and has further shown that starting boiling in cold water is counterproductive. Shocking the eggs by rapidly cooling them helped, and cooling them in ice water for 15 minutes or longer gave more successful peeling. Shocking was also found to remove the dimple in the base of the egg caused by the air space.[22]

Dishes featuring boiled eggs

Boiled eggs often form part of larger, more elaborate dishes. For example, a boiled egg may garnish a bowl of ramen (often first marinated in soy sauce), be baked into a pie such as a torta pasqualina,[23] or be encased in aspic (similar to the French dish œufs en gelée, which features poached eggs[24]), be chopped and mixed with mayonnaise to form egg salad, or be deep-fried and then baked within a serving of Lamprais.

See also

Notes

- The American Egg Board, an industry group, recommends against piercing shells on food safety grounds: "Piercing shells before cooking is not recommended. If not sterile, the piercer or needle can introduce bacteria into the egg. Also, piercing creates hairline cracks in the shell through which bacteria can enter after cooking.", Basic Hard-Cooked Eggs Archived January 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, American Egg Board

References

- Bauer, Elsie. "How to Steam Hard Boiled Eggs". www.simplyrecipes.com.

- "Important Cooking Temperatures". Edinformatics.com. 17 November 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Vega, César; Mercadé-Prieto, Ruben (2011). "Culinary Biophysics: On the Nature of the 6X°C Egg". Food Biophysics. 6 (1): 152–9. doi:10.1007/s11483-010-9200-1.

- Blumenthal, Heston (12 November 2014). "Series: The Do Something expert Index How to boil an egg, the Heston Blumenthal way". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "Plan Under Way to Help Lessen Risks from Contaminated Eggs". FDA Consumer magazine. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- J. D. Schuman, B. W. Sheldon, J. M. Vandepopuliere, and H. R. Ball, Jr. Immersion heat treatments for inactivation of Salmonella enteritidis with intact eggs. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 83:438–444, 1997.

- "Fine Manners for Fine Dining". Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- "Egg with Toast Soldiers". Archived from the original on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- "Soft-Cooked Eggs, Medium-Cooked Eggs, and Hard-Cooked Eggs". Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- "How long to Boil Eggs". Eatbydate.com.

- "The Egg Files Transcript". Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- Belle Lowe (1937), "The Formation Of Ferrous Sulfide In Cooked Eggs", Experimental Cookery From The Chemical And Physical Standpoint, John Wiley & Sons

- Harold McGee (2004), McGee on Food and Cooking, Hodder and Stoughton

- "Learn More About Eggs". Archived from the original on 2008-08-22. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- "Egg-ucation". Retrieved 2006-12-19. – suggests boiled eggs can be stored refrigerated for one week

- "About Eggs". Archived from the original on 2006-11-07. Retrieved 2006-12-19. – suggests boiled eggs can be stored refrigerated 2–3 weeks

- "Shell Eggs from Farm to Table". Fact Sheets: Egg Products Preparation. United States Department of Agricultural Food Safety and Inspection Service. April 20, 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

When shell eggs are hard cooked, the protective coating is washed away, leaving bare the pores in the shell for bacteria to enter and contaminate it. Hard-cooked eggs should be refrigerated within 2 hours of cooking and used within a week.

- Pollack, Hilary; Sen, Mayukh (22 January 2018). "I Am Mystified and Horrified By the Long Egg". Munchies. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- "Call For Submissions: The Long Egg". FreakyTrigger. 18 August 2006.

- López-Alt, J. Kenji. "The Food Lab: The Hard Truth About Boiled Eggs". Serious Eats. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- Eggs Under Pressure By Mr. Brown. Published on March 18, 2016.

- https://www.seriouseats.com/2014/05/the-secrets-to-peeling-hard-boiled-eggs.html

- "Giant Green Pie (Torta Pasqualina)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Beck, Simone; Bertholle, Louisette; Child, Julia (1964). Mastering The Art Of French Cooking. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 547.

External links

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boiled eggs. |

| Look up boiled egg in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Basic Hard-Cooked Eggs, American Egg Board

- Boiling an Egg - Science Background

- Boiling of eggs for molecular gastronomers

- wiki articles on how to boil an egg, poach an egg, and soft boil an egg. An overview of all processes for boiling eggs.