Blockade of Western Cuba

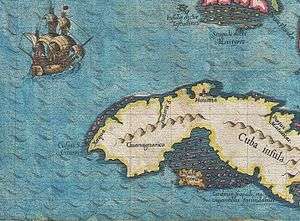

The Blockade of Western Cuba also known as the Watts' West Indies Expedition of 1591 was an English privateering naval operation that took place off the Spanish colonial island of Cuba in the Caribbean during the Anglo–Spanish War. The expedition along with the blockade took place between May and July 1591 led by Ralph Lane and Michael Geare with a large financial investment from John Watts and Sir Walter Raleigh.[8] They intercepted and took a number of Spanish ships some of which belonged to a Spanish plate convoy of Admiral Antonio Navarro and protected by the Spanish navy under Admiral Diego de la Ribera intending to rid English privateers.[9] The English took or burnt a total of ten Spanish ships including two galleons, one of which was a valuable rich prize.[7][10] With this success and the loss only one ship the blockade and expedition was terminated for the return to England.[11] The blockade was one of the most successful English expeditions to the Spanish Main during the war militarily and financially.[7][12]

Background

In early 1591 an English fleet had been organised for a raiding expedition to the Spanish West Indies. The expedition had been financed in a joint stock venture and was organised into three fleets.[3] The first and main fleet was financed largely by John Watts but also had investment from Walter Raleigh, Paul Bayning and Sir Francis Drake.[7][12] The expedition's captain was William Lane of the 120-ton Centaur, while second in command was Captain Michael Geare in the 150-ton Little John[3] and the 80-ton Pegasus under Captain Stephen Michell and the pinnace Fifth Part.[10] The back up fleet was composed of two ships – Margaret of 60 tons under Captain Christopher Newport and the 50-ton Prudence under Captain John Burough.[7] The other part of the fleet had been financed largely by Sir George Carew – the 200-ton Hopewell (alias Harry and John) of Captain William Craston, the 130-ton bark Burr of under Captain William Irish, the 35-ton Swallow under Ralph Lee and the 30-ton Content under Captain Nicholas Lisle.[7][13] They were to attack and raid any Spanish or Portuguese shipping in the area of Hispaniola and Cuba with the aim of making a profit.[14]

Expedition

They set out from Plymouth in the Spring of 1591 swinging by way off the coast of Spain as a ruse to fool the Spanish as to their real destination.[6]

In April 1591 while off Cadiz Margaret under Newport and Prudence caught site of a large Spanish ship; a large bark which was soon captured. Newport found in the prize bullion, money, hides, precious stones, wine and other valuables.[7] Newport sent the prize home and the fleet proceeded west toward Cuba and rendezvoused with some of the fleet between Saint Kitts and Puerto Rico in May 1591.[3] Despite the weather separating many ships they all arrived in the Bahamas a week later.[15]

The expedition's first success came in late May when a 150-ton Spanish merchantman Rosario of Master Francisco González was captured by Marageret and Prudence near La Yaguana off Hispaniola.[7] Rosario’s crew was released but their vessel was pillaged for any valuables of which some were found. The prisoners informed the English that a Spanish fleet of seven galleons, two galleys, and two pinnaces with 2,000 men in total were destined to arrive in the area of Western Cuba.[7] This force was under the command of Admiral Don Diego de la Ribera in command of the Tierra Firme fleet. He had left Havana in early June to sweep any English privateers from the designated area as this was in anticipation of a plate fleet led by Antonio Navarro de Prado.[10]

Blockade

The English therefore decided on a blockade of Western Cuba and risked the confrontation of Ribera.[2] The English took up position near Corrientes in mid June to await the arrival of Spanish ships.[15]

Corrientes

On 23 June Burr, Hopewell, Swallow and Content arrived between Cape Corrientes and Cape San Antonio and soon sighted six sail.[10] Having believed they might have been treasure ships from Cartagena the English closed, only to discover the force was Ribera’s 700-ton flagship Galleon Nuestra Señora del Rosario, Vice Admiral Aparicio de Arteaga’s 650-ton Magdalena, two other large galleons, and a pair of galleys.[10] Despite being heavily outnumbered the English stood formation and a long-range exchange commenced at 7:00 am. This lasted for the next three hours, after which the English formation scattered. During this time Burr exploded from a catastrophic fire in the magazine either from a stray Spanish shot or by complete accident.[15] Irish and sixteen survivors were rescued by the Swallow which soon after withdrew from the area.[2] Soon after the 100-ton galleys San Agustín and Brava then closed in on the two remaining English vessels and attempted to board by grappling.[13] They were however repelled by heavy gunfire from Hopewell and Content in a defensive position.[6] The Spanish galleys, unable to make an impression and suffering considerable damage then stood off and rejoined de la Ribera's galleons.[13] Soon after the English ships departed and sailed to Cape San Antonio but sighted nothing of value.[6] Content got lost during the night and was unable to find any other ships and may have headed all the way to Florida.[15]

On 29 June Hopewell and Swallow returned to Cape Corrientes to find no sign of any Spanish ships under de la Ribera.[10] Both ships soon met up with Centaur, Pegasus, Little John, Prudence and Fifth Part. They were joined by Captain John Oker’s Lion a lone ship from Southampton operating independently.[2]

On 3 July while part of the formation was watering inshore off Corrientes; Pegasus and Centaur caught sight of a number Spanish ships.[10] After a quick pursuit they overhauled and captured the 150 ton Spanish armed merchantmen Santa Catalina under Captain Martín Francisco de Armendáriz, and the 100 ton escorting frigata Regalo de Dios. At the same time the other escorting frigata was trapped and captured by Lion and Swallow.[10] The Spanish ships had been bound from Santo Domingo to Havana carrying valuables which included precious stones and hides.[3]

Havana

.jpg)

On 5 July, the English agreed to all sail together with their prizes until they passed the Cuban capital. Upon having reached Matanzas; Prudence and Lion continued up the Old Bahama Channel toward England with their prizes.[10] The next day Centaur, Pegasus, Hopewell, Little John, Swallow and Fifth Part reversed course to take up station to blockade the west of Havana.[10] Despite the risk of the more heavily armed galleons of Ribera aimed at destroying them, the six English ships awaited incoming Spanish ships.[7]

On the morning of 15 July Pegasus and Little John sighted a large Spanish ship.[6] The English sailed towards her, attacked the ship, and after heavy hand-to-hand combat and a number of casualties, they boarded and overwhelmed the Spaniard forcing its surrender.[10] The captured Spanish ship was the 300-ton Spanish galleon which turned out to be the San Juan; her captain Agustín de Paz was heading from Veracruz to Havana. The San Juan was thoroughly pillaged, after which was then burned with the prisoners taken ashore.[6] From the prisoners and documents they learned that a Spanish convoy was behind the San Juan.[10] On the same day more success came to the English as Swallow, Centaur, Hopewell and Fifth Part pursued four Spanish coastal ships which were surrounded and captured.[5] They were pillaged and the two were used as store ships while the other two were burned.[6]

Early the next day, the first elements of the main Spanish convoy had arrived in the area from Veracruz under Admiral Navarro.[10] The English took watch and an opportunity came about when one of the lookouts spotted a lone ship; noted as being too far ahead of the rest of the convoy.[2] At midday Centaur and Little John attacked and boarded the vessel from the rear, while the Pegasus pounded the starboard side of the ship.[6] After a sharp half an hour fight in which William Lane was injured, the ship was taken.[5] The captured prize was a 240-ton armed merchant galleon from Seville, the Santa Trinidad under Captain Alonso Hidalgo.[10]

The Santa Trinidad prize proved so rich that Lane immediately ordered the English to quit their watch outside Havana and protect the ship at all costs.[8] They sailed home before the rest of the Spanish plate fleet along with Ribera sortied on its homeward leg.[5][7]

Aftermath

The English fleet arrived at Plymouth a few months later with the eight captured ships amid much rejoicing.[6] In all Watt's expedition was a huge success – eight prizes were taken in all worth a total of £40,000 which produced on investment of at least 200 per cent regardless of embezzlement and pillage which crew members committed to supplement their normal one third share granted in lieu of wages.[2] Half of this went to Queen Elizabeth I, the Lord Admiral Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham with the rest shared between Watts and Raleigh.[12] The Trinidad was the richest yielding £20,000 alone with silver, hides and cochineal.[7] Watt's had taken most of the prizes and the money, and Carew who funded a small part asked Sir Julius Caesar to intervene on a matter of fair distribution.[16]

The Spanish on the other hand had been frustrated – de La Ribera had failed to clear any of the English from Western Cuba and could do little about the blockade.[5] The Spanish Governor of Cuba Juan de Tejeda complained bitterly particularly as the English had sent him letters and compliments during the blockade:[5]

for every hour they sail under my nose; in future I would like to be prepared that the enemy may not so insult me without my being able to get at him.[2]

The blockade of Western Cuba was one of the most successful English expeditions of the war militarily and financially.[7] The following year more expeditions were launched by the English led by Christopher Newport and funded again by Watts and Lane.[5] Although they didn't repeat the huge success of the previous years expedition, their operations forced the Spanish to delay the departure of two Treasure fleets. As a result, they only reached Spain in the Spring of 1593.[17]

References

- Citations

- Watt's ships, scored a tremendous success in 1591. Andrews p 106

- Bradley pp 106–07

- Quinn pp 333–34

- Wernham, Richard Bruce (1980). List and analysis of state papers, foreign series: Elizabeth I June 1591 – April 1592 Volume 3. Public Record Office. p. 413.

- Andrews pp 167

- English privateering voyages to the West Indies, 1588–1595, Volume 111. Hakluyt Society at the University Press. 1959. p. 127.

- Dean pp 162–63

- "Publications of the Catholic Record Society". Catholic Record Society. 52: 153. 1959.

- Childs p 183

- Marley p 124

- Wright, Irene Aloha (1951). Further English Voyages to Spanish America, 1583–1594: Documents from the Archives of the Indies at Seville Illustrating English Voyages to the Caribbean, the Spanish Main, Florida, and Virginia. University of Michigan: Hakluyt Society. p. LXXVIII.

- Nichols/Williams p 66

- Southey p 389

- Richard Hakluyt (1914). The Principal Navigators Voyages Traffiques And Discoveries Of The English Nation Volume X. James MacLehose And Sons.

- Andrews pp 165–66

- Andrews p 26

- Bradley p 100

- Bibliography

- Andrews, Kenneth (1984). Trade, Plunder and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480–1630. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521276986.

- Bicheno, Hugh (2012). Elizabeth's Sea Dogs: How England's Mariners Became the Scourge of the Seas. Conway. ISBN 978-1844861743.

- Bradley, Peter T (2010). British Maritime Enterprise in the New World: From the Late Fifteenth to the Mid-eighteenth Century. Edwin Mellen Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0773478664.

- Dean, James Seay (2013). Tropics Bound: Elizabeth's Seadogs on the Spanish Main. The History Press. ISBN 9780752496689.

- Childs, David (2014). Pirate Nation: Elizabeth I and her Royal Sea Rovers. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781848321908.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere. ABC CLLO. ISBN 978-1598841008.

- Mark, Nicholls; Williams, Penry (2011). Sir Walter Raleigh: In Life and Legend. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441131829.

- Quinn, David B (1985). Set Fair for Roanoke: Voyages and Colonies 1584–1606. America's Four Hundredth Anniversary Committee. ISBN 9780807816066.

- Southey, C.T (2013). Chronicle History of the West Indies. Routledge. ISBN 9781136990731.

- Wagner, John (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Elizabethan World: Britain, Ireland, Europe and America. Routledge. ISBN 9781136597619.